Keiler Roberts has made her comics career illustrating moments of her own life. Since starting her minicomic Powdered Milk, through to a recent string of books published by the influential but now-defunct publisher Koyama Press, her focus on the quotidian, in-between moments of life has remained. She drops the reader into awkward moments of established relationships without context, leaving them to figure out meaning without an expository helping hand. This approach has remained roughly the same for the last decade; what makes her new book, My Begging Chart, (her first with Drawn & Quarterly) feel different is that our relationship to these liminal, domestic moments that are her focus have been exacerbated after a year indoors.

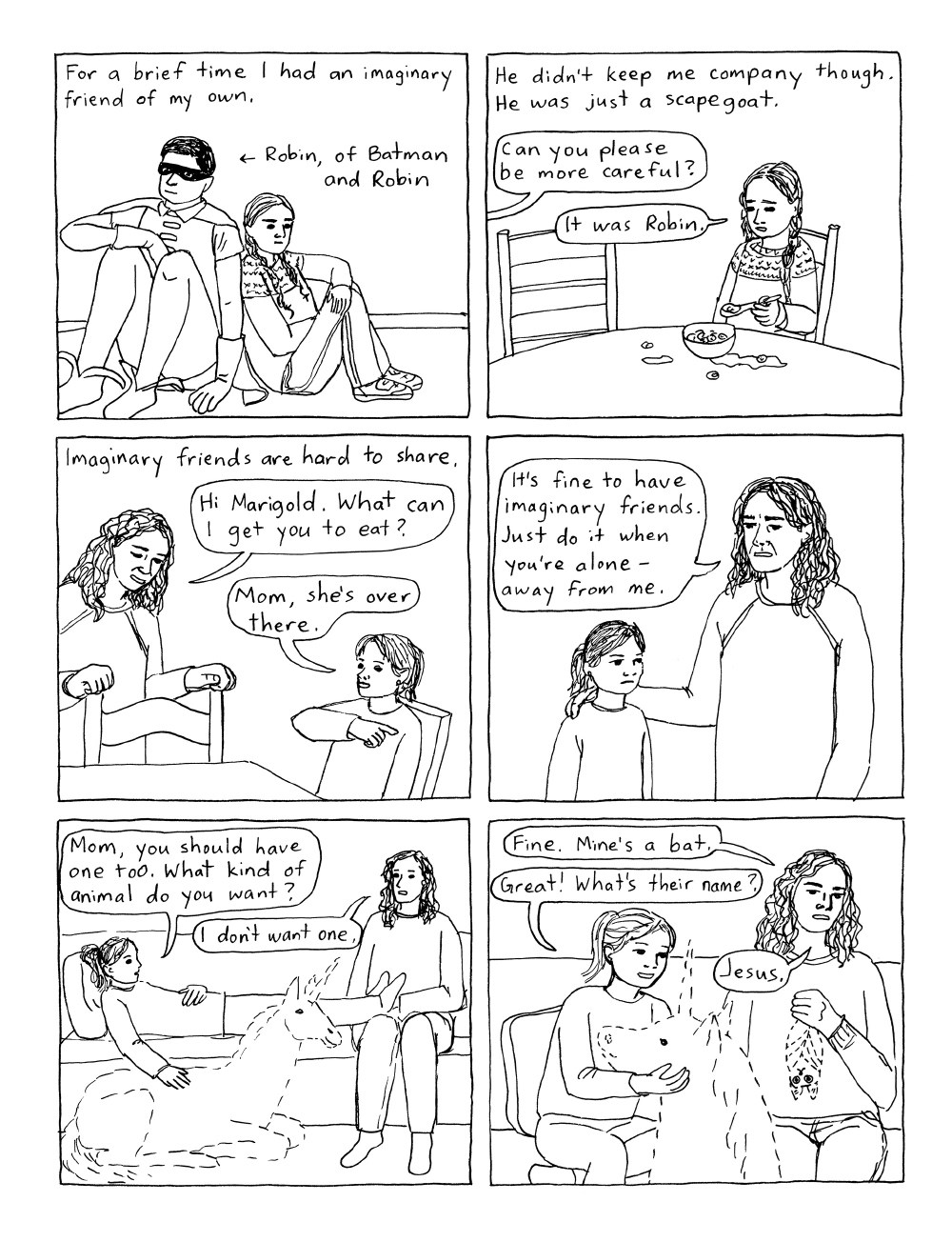

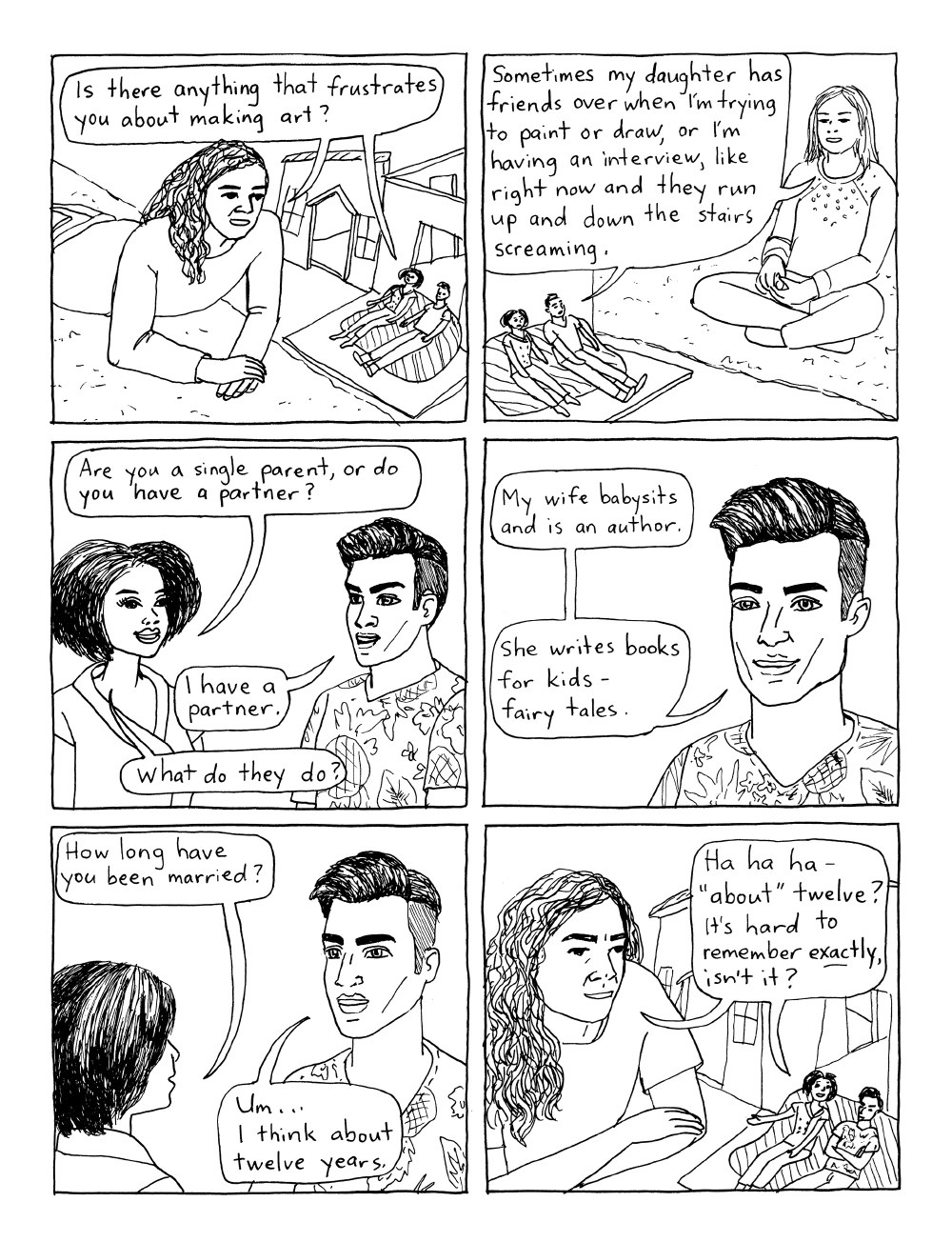

These are books of not-quite-anecdotes, vignettes of anti-climax. Roberts doesn’t tell a story, rather she reveals the parts of life left out of stories. Slow but short moments that don’t really go anywhere but do have, at their heart, a hint of humor and character, that when put together across a book create a stronger, realer sense of a person than most traditional narratives can achieve. Roberts shows herself and her family at vulnerable moments. But not vulnerable as in unsafe or extremely emotional, more vulnerable as in unperformed, looking at them when they don’t feel looked at.

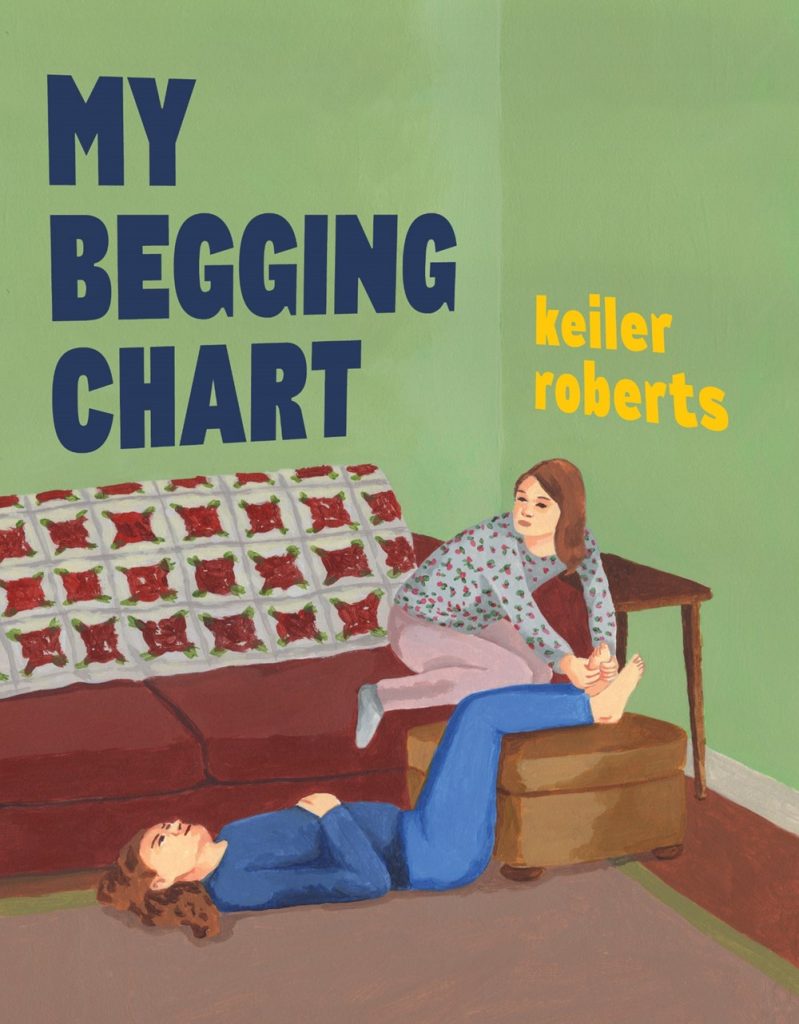

Roberts’ unobtrusive style, made up of just a few big panels to a page, scratchy ink lines, and unexpressive faces aids in building the feeling that we’ve just been dropped into real moments, watching people unprepared to be watched. Her pages are left with a lot of white space, the form following the content, these are quiet pages. Her people look a little awkward, sometimes out of step with their environments, sometimes their bodies are a little off. It’s an unglamourous space and Roberts has an unglamourous style that fits perfectly with it. Just as Roberts doesn’t give context for the events, the sparse art leaves us space to figure out what is happening, fill in with details from elsewhere in the book, from our own lives. By not doing too much, Roberts makes reading her comics a more participatory experience.

This is part of how comics works, of course, we fill in the movements and the moments in between the panels. The space in the gutter is a vital element of sequential storytelling. Yet Roberts expands this idea of space in comics storytelling beyond that essential space between the panels, bringing the reader further into the act of comics storytelling. Her books are situated in a familiar setting, a setting of domesticity, family moments that most will at least have a touchpoint with, meaning a reader can build out a wider picture of what’s happening without being dictated to. Roberts provides us with the heart of a moment, and we are left to figure out how that fits into a context, both in terms of space and time, as well as plot. As she focuses on the key aspects of these awkward beats of emotion, humour, or vulnerability, the rest is left to us.

The space in comics usually points towards the passage of time. When we see a consistent grid of panels, with consistent gutters, we would assume that means a consistent passage of time. The structure of panels usually implies a temporal structure, but time passses weirdly here. The form provides a sense of structure, but Roberts doesn’t use that structure conventionally. Time moves sporadically. One scene may only need one panel where others need four pages, but, somehow, they will still feel as long as each other. It’s almost as if everything is happening simultaneously, frozen in place. Where space in comics would normally convey a passing time, here time doesn’t really matter.

There are a few things that should be markers of time within the text, the length of the husband Scott’s beard and head hair changes for example, but they don’t feel like time is passing in a conventional sense. Scott’s beard might be vastly different lengths in different scenes, but that doesn’t mark any kind of change in the story, nor does it grow in any discernible direction, it’s just random lengths in random scenes. Like with the plot, the exposition, and the art style, My Begging Chart is notable in its lack of time. One scene doesn’t lead to the next, all these moments are living next to each other but isolated, only connected by the fact that it’s the same people.

This has been a feature across most of Roberts’ body of work, but it hits more palpably in My Begging Chart, a book released in 2021, after we have all lived lives of domestic awkwardness without our usual measures of time. Our lives have been like the stories of this book, frozen and still, not able to progress, a selection of unevents around the kitchen counter. We stare at undusted ceiling fans that stay undusted despite having the time and capacity to dust. We remember our childhood imaginary friends, wondering if we can shift responsibility onto them again. A structured experience of time fades in successive lockdowns, when we’re stuck indoors, doing the same things with the same people day in day out. All that’s left to be noted is the weirdness of our domestic interactions. The only close relationships that we can hold onto are with those that live with us, and they are always there. No beginning and no ending, a continual slip of shapeless moments.

And that’s why Roberts’ work feels so fitting right now, because her focus has always been on the quotidian, awkward in-betweens of life. She doesn’t need traditional storytelling structures because the parts of life that she addresses aren’t stories. They are important parts of life, they take up the majority of life. While they don’t have the shape of stories that get passed on, they do create a picture of someone’s character in a much deeper way than big events can. Reading My Begging Chart in 2021, after a year and a half stagnating inside, has a new universality to it compared to her previous work.

A global pandemic has thrown us into this kind of life that Roberts can illustrate so well, but we’re just tourists there really. Across her work, she has been open about her struggles with physical and mental health conditions, casually dropping mentions of her bipolar disorder and MS as background facts of life that don’t need explicit expansion, but whose effects can be seen in the way she presents her life. She has been living in health crises for years, and that’s why she is so effective at conveying the tone of maintaining normalcy through crisis. Hopefully our collective experience that has thrust her work to new levels of relatability will be remembered, not as an aberration, a year to be moved on from, but as a revelation, a moment when we can see and feel how crises of health affect people’s day to day lives. The question that I am left with is whether this new-found universality to Roberts’ work, felt in My Begging Chart, will still be felt in her next work.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply