Hiromi Goto’s debut graphic novel—after having written adult and young adult fiction, as well as poetry—explores an older woman’s choice of how to live out the remainder of her life. The work opens with a prologue showing Kumiko’s sneaking out of an assisted living facility to live on her own, despite her daughters’ concerns. Throughout the rest of the work, she faces the realities of her mortality and the limitations of her age, while trying to craft a life for herself with the time she has left.

Kumiko is quite clear-eyed about her death. She knows death has been stalking her since she left the facility. Rather than avoid that reality, she confronts death head-on. In fact, her life early in the work is a balance of her everyday life and death that follows her around. Goto explores the sounds of both, as she highlights the sounds of normal life, whether creaky signs, swallowing pills, or the ding of emails arriving in Kumiko’s laptop. Those are contrasted with the sounds Death makes, such as the bang when it slams into the table on its way to try to drown Kumiko.

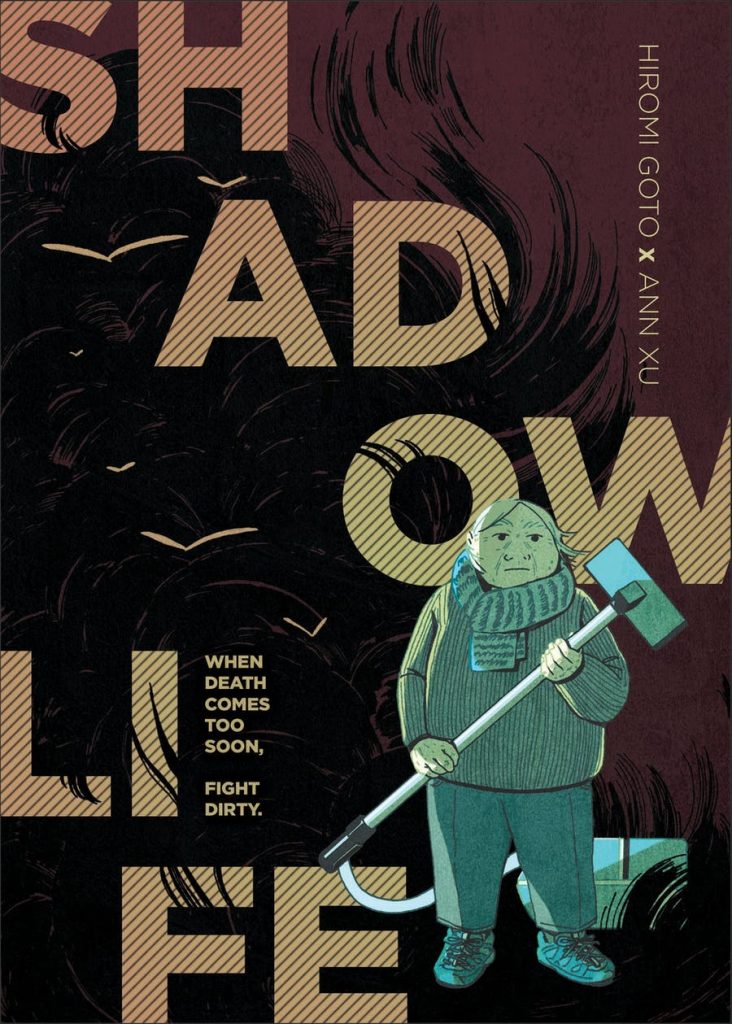

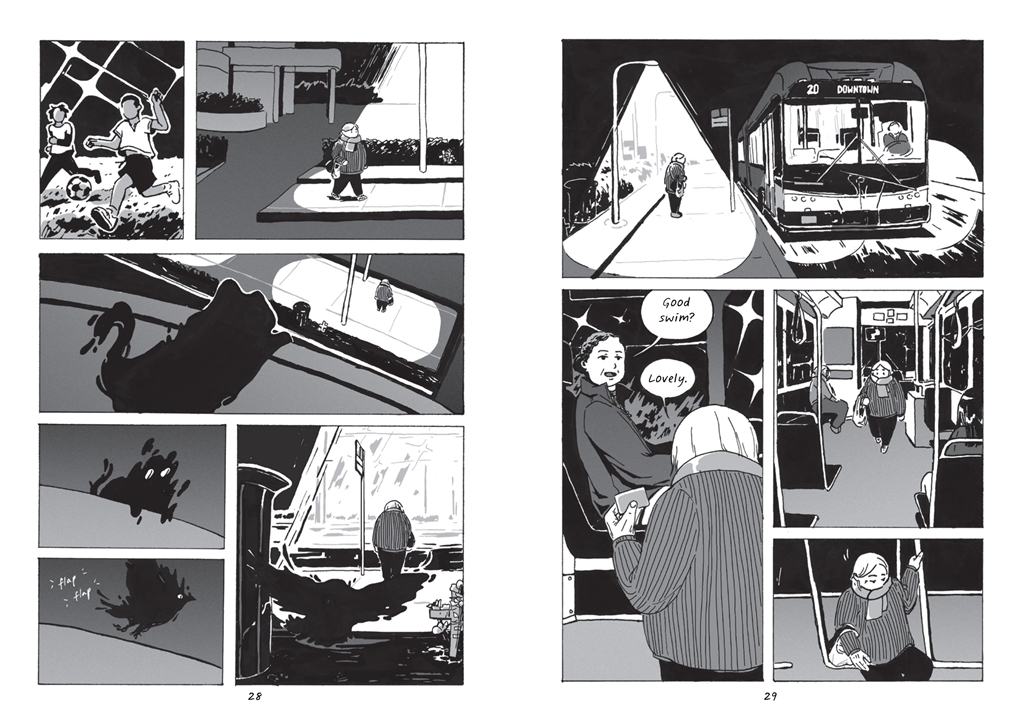

Ann Xu’s art reflects the frequent presence of Death, as the work is all in black and white, with a heavy emphasis on lighting and shadows. In some sketches included at the back of the work, Xu even comments about one scene where she portrayed the bright lights against the night sky. That contrast runs throughout the book, whether Death is actively portrayed or not. The frequent use of shadows reminds the reader that Death is around, whether Kumiko sees it or not.

Goto also uses magical realism to portray the death-haunted nature of Kumiko’s life, moving beyond the shadowy figures Death takes when following her (usually a cat, but often a crow and perhaps a spider—that figure is vague as to whether it’s Death or something else). Kumiko is able to trap Death in a vacuum cleaner, adding salt on top of it to keep Death from crossing that threshold. Kumiko’s dead husband and other figures who appear out of graves repeatedly show up as Kumiko goes about her daily life, though it is her husband who makes the most frequent appearances. Most of that time, he appears as a set of soggy shoes that walk behind her, given that Samuel died in a car accident that Kumiko survived but caused Samuel to drown.

In fact, when Kumiko is in the hospital, the spider who appears to her explains that she has already cheated Death twice: once when she survived the car crash and the second when Kumiko donated a kidney to save her daughter’s life. The spider appears in a long sequence where Kumiko seems to be in a limbo state, somewhere between life and death, though that section remains unclear. What matters is that Kumiko deals with the reality of her mortality. When she has trapped Death in the vacuum cleaner, she admits, “No one cheats Death. Who wants to live forever?” (126). She doesn’t want to avoid Death, but she does want a bit longer to live on her own terms, not how she was living in the assisted living facility.

Goto is also honest about the challenges of an older woman living on her own. At various points, Kumiko falls and breaks her arm, in addition to losing her keys and phone. She has begun forgetting to take her pills, as well, though Death might have something to do with that problem, as its minions seem to be hiding them. Her daughters constantly worry about her, even tracking down where she lives (she hadn’t told them after she left the facility) after they’ve threatened to call the police to find her. However, she also enjoys life on her own, taking pleasure in simple dinners and going for a swim before riding the bus home.

She also learns how much she needs community, not merely to survive on a physical level, but on an emotional level. Yusuf, who lives in the same apartment complex, helps her several times early in the work, even carrying boards she finds beside a dumpster back for her. The young women she showers with after swimming, despite their not knowing her, point out a mark on her back where Death touched her, leading her to the doctor for a biopsy. When she falls and breaks her arm, she relies on Meena—a woman who sold her a vacuum cleaner—to help her without having to go to the hospital. She’s afraid her daughters will see that as evidence Kumiko is unable to take care of herself. Instead, Meena takes her to Alice, a woman Kumiko was in love with before she married her husband. Alice uses her military training to bandage Kumiko’s arm, though she ultimately encourages Kumiko to go to the hospital for real treatment, as well.

These two strands—the reality of aging and mortality, coupled with the need for community—drive the entire book. Goto explains that she has always written about older, Asian women, as her life was shaped by her Oba-chan, her grandmother, who raised her. Goto even believes she writes about these women to try to craft stories of who she can become. At the end of the Author’s Note, Goto writes, “More of us feel closer to death than we have ever felt, but it is possible to live vibrantly, even near Death’s shadow. Friendship, compassion, generosity, and caring cast the brightest light.” Goto’s work confronts these ideas head-on.

Kumiko lives in her final days or months or years, as it’s unclear what her fate will be, but she reshapes how she wants to live by being proactive. She carves out a life of her own, even fighting Death to have a bit more time to do so. As Goto notes, the pandemic has brought us all closer to the reality of our mortality. Her graphic novel wants to remind us to live vibrantly and cast the brightest light we can in whatever time we have.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply