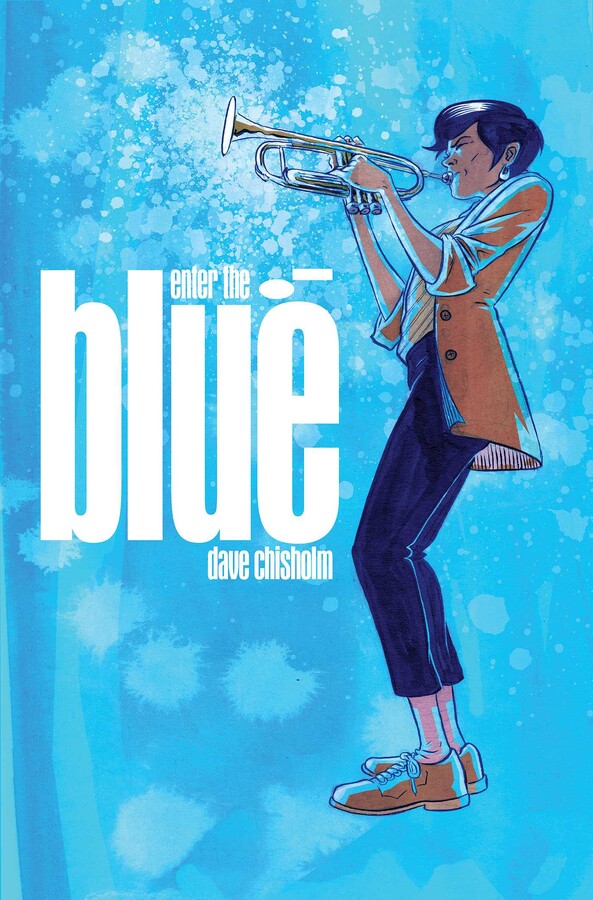

Jessie Choi is a talented jazz trumpeter, she has the potential to be a great performer, but, when she performs, her anxiety gets the better of her and she freezes up. The first chapter (though it’s more of a prologue in function) of Dave Chisholm’s new graphic novel, Enter The Blue, shows Jessie at the end of her time studying music with her mentors, a married couple of classic jazz musicians Jimmy and Margot, trying to offer her reassurance and encouragement. This falls on deaf ears as the book jumps forward a few years; Jessie is now teaching and has not played her trumpet in years. Meanwhile, Jimmy is mourning the death of Margot, longing to relive their connection. When Jimmy collapses during a set, Jessie has to pick up her trumpet and go on a journey into a mysterious, timeless realm of musical euphoria known as “The Blue.”

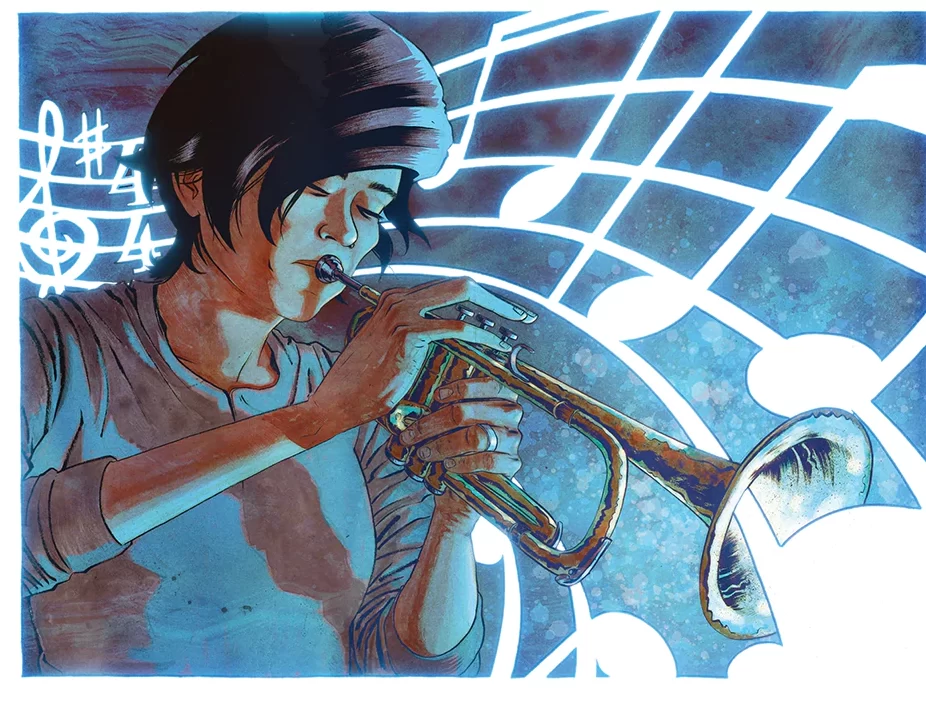

In the world of Chisholm’s book, “The Blue” is a literal manifestation of getting in the zone while improvising, it’s a dimension some musicians can enter when they commit to letting go, a timeless place that connects them to the history of music. It allows you to talk to the great players of history, see the performances that let them into “The Blue”, get guidance and mentorship. It’s a space of learning and nostalgia, it’s somewhere that you might like to stay for a while. It’s where the book is the most visually dynamic, switching suddenly as we enter “The Blue” from single to double page layouts, Chisholm’s paneling gets looser, the pages are washed in deep blues, and scaling becomes flexible as Jessie is greeted with giant ghosts of her idols.

This is in stark contrast to the rest of Enter The Blue, where Chisholm has a very grounded and naturalistic style, particularly in the colors, that almost feel like they’re working hard to be unremarkable so that when there is this change it has the biggest impact that it can. His pages themselves tend to be simply laid out, with his most effective pages coming to a single focal point of a single, somewhat isolated, either at the centre or bottom of the page, delivering a momentary punch in the rhythm. Chisholm’s style is very straightforward, using simple and clear techniques to keep the story moving. These aren’t groundbreaking things in comics storytelling, but they are proficient and well done here. Chisholm knows what he’s doing even if he doesn’t reinvent the wheel.

Usually that wouldn’t be a problem, and I wouldn’t even call it a problem here, but there is something that irks about it here. In the book, Chisholm keeps coming back to a Thelonious Monk quote, “a genius is one most like himself.” Jessie’s arc is about taking the technical proficiency that she has mastered and not worrying so much about messing up, instead embracing the uniqueness and flaws of improvisation and herself. So it feels a little off that this book is technically well put together, but lacking just a little in improvised flair. The art is too still and precise to fully embody what the book is saying.

Chisholm is an academic and musician and some of his previous comics work has been non-fiction, like 2020’s Chasin’ The Bird about Charlie Parker’s time in Los Angeles in 1945. His precise and technical style makes sense in that context – it feels grounded in a realism, accuracy, and clarity that is useful for both teaching and non-fiction. While Chisholm’s choice to keep this less grounded story in a similar grounded style, albeit with some pushing at the edges with the fantastical sequences in “The Blue”, works, it lacks something. His passion and knowledge of subject and craft (both in terms of comics and jazz) is clearly deep and refined, the moments in the book where Chisholm’s excitement is most palpable are when he gets to talk about the history of jazz, when he’s writing didactic voices of jazz legends.

Looking at a book with a similar concept, Blue in Green by Ram V and Aand RK, a graphic novel from last year with a similar idea where jazz is a route to a supernatural world but with a horror spin (which I wrote about for TCJ), we can see an artistic approach that leans into a responsive, chaotic, and dirty rhythm. It’s like jazz, innovative and unstable. While it’s not a perfect 1:1 comparison, the two books take their concepts to very different places, and Blue in Green is a much darker story, the difference in approach is noticeable, leaving Enter The Blue looking very still.

Unlike music, comics are silent, but the two do share important formal qualities. The underlying delivery of comics relies on rhythmic aspects coming from panel structures laying out the beat of the page, with color and linework building textured melody on top. There are lots of comics that focus on music, including Chisholm’s own, and Enter The Blue is a strong example, Chisholm creates a strong rhythm within his pages and an effective melody with some interesting moments, though a little stayed and lacking in anything particularly innovative.

In a way, this is a shame, as the subject matter is a dynamic and loose style of music, although, it does mirror where Jessie is at for most of the book. She’s anxious and trepidacious, struggling to see past technical skill and personal doubt in order to fully embrace the power of improvisational art. This is also the impression that this book gives, a strong understanding of form, high technical skill, and clear passion, but also restraint that is blocking access to a world of greater potential.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply