Nearly two decades ago, Lynda Barry came up with the term autofictionalbiography for graphic memoirs that constitute part truth, part fiction. In her book One Hundred Demons she wrote, “Is it autobiography if parts of it are not true? Is it fiction if parts of it are?” Cartoonist Kiku Hughes’ debut graphic narrative Displacement works with a similar blending of genres. It lies somewhere between “fact and fiction, between memory and history” (Hughes, 2020, p. 279). Displacement is primarily about a Japanese-American teenager who inadvertently travels back in time to the Japanese-American incarceration camps (1) during World War II. The author-protagonist, the eponymous Kiku, is stuck there for the length of the time her grandmother, Ernestina, was incarcerated, first at Tanforan, California, then at Topaz, Utah. Graphic memoirs largely rely on memory as the primary source of information as well as a visualization strategy to show the reader what the author-protagonist sees/remembers. Since the need for explanatory verbal interjections is omitted by visuals that self-evidently delineate timelines, author-protagonists figuratively but seamlessly move back and forth between the past and the present, as well as between the sociopolitical and the personal. In this respect, Displacement is similar to other titles in the genre. However, what distinguishes Displacement from other graphic memoirs is that it forays into the realm of fantasy through its use of time travel as a major plot device. Described as “travelling through memory” by the protagonist’s mother (Hughes, 2020, p. 234), it is used to make visible how trauma is passed down through generations, how it is embedded into the collective memory of a persecuted community. Hughes writes,

I think sometimes a community’s experience is so traumatic, it stays rooted in us even generations later. And the later generations continue to rediscover that experience, since it’s still shaping us in ways we might not realize.

Kiku Hughes, 2020, p. 234

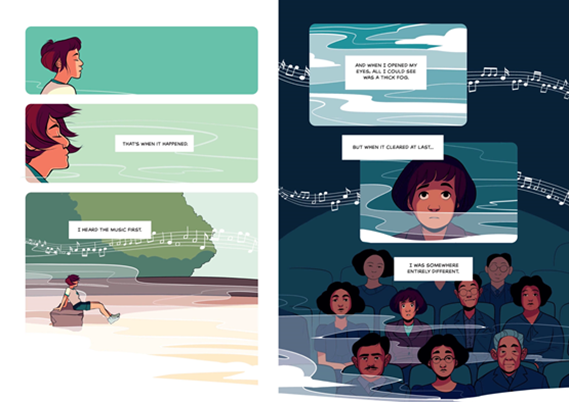

The first displacement in the comic occurs when Kiku is in San Francisco with her mother. They are on their way to look for the house her grandmother had grown up in, before she was forcibly moved out and taken to an incarceration camp, along with thousands of other people of Japanese descent in the West Coast (6). Kiku is swept up by a wave of thick fog that takes her all the way back to the 1940s. At the camps, although they never truly meet, she is always in close proximity to the younger version of her grandmother. This evocative use of a personal narrative makes Hughes’ historical research-driven text accessible and engaging. It provides critical insight into life at the camps where people of Japanese descent were stripped of their civil liberties under the guise of national security. It shows how, despite their limited circumstance, they tried to create a semblance of community and resistance.

What makes Displacement particularly compelling and topical are the parallels Hughes draws between the incarcerations of Japanese-Americans during World War II and current anti-immigrant policies, the 2017 Muslim ban, and the atrocities at the Mexico-US border. The character’s displacement to the incarceration camps is preceded and followed by two distinct scenes of Kiku’s mother watching news leading up to the 2016 Presidential election.

As they both watch the news with horror-stricken faces, Kiku asks her mother if she thinks what happened to her grandparents could happen again. By juxtaposing her Japanese-American family’s experience in the camps with present day politics that continue to disenfranchise immigrants and racial minorities, Displacement functions as a history lesson. But it is also a lesson in how history may repeat itself if we do not actively resist bigotry. She writes,

The persecution of a marginalized group of people is never just one act of violence—it’s a condemnation of generations to come who live with the ongoing consequence. We may suffer from these traumas, but we can also use them to help others and fight for justice in our own time.

Kiku Hughes, 2020, p. 277

During her time at the camps, Kiku learns to question previously held misconceptions that the “no-no boys” (those who answered “no” to Question 27 and 28 in the “loyalty questionnaire”) were troublemakers; she learns to “deeply respect their resistance and refusal to jump through the hoops their country was demanding of them” (Hughes, 2020, p. 171). This is perhaps what the story is really about: resistance.

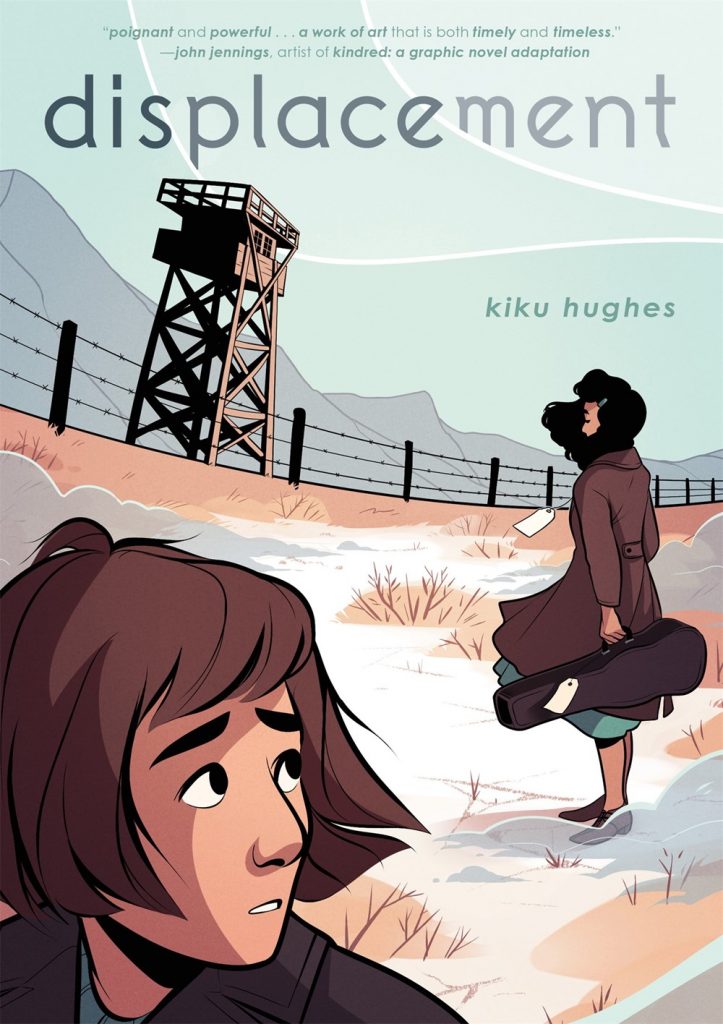

It also bears mentioning that Hughes uses the comic medium in a way that mirrors the intergenerational nature of trauma and memory. She uses the fluidity afforded by the image-textual space to masterfully weave together the complex history of the incarceration camps with present-day exclusionary politics, spread across three generations and multiple locales ranging from San Francisco, Tanforan, Topaz, Seattle, to New York. Displacement boasts of artwork that is striking, both in its visually appealing simplicity and its use of bright saturated colors; a teal and coral color palette is interspersed with sepia tones, and with heavy use of beige and brown to distinguish between the past, the present, and the camps. Hughes also generously makes use of silhouettes and a range of different perspectives to add depth and visual nuance to her scenes. Much of the storytelling is done through pictorial details, including that of the background. A considerable number of splash pages are entirely wordless, yet they are some of the most memorable images in the book.

There is no hatching in her art, and Hughes creates shadows through darker flat colors; the panels have rounded edges and are borderless throughout the narrative. The linework is clean, crisp, and consistent, yet never monotonous. Hughes has a knack for finding the perfect balance between abstraction and detail, which guides the reader’s attention to where it needs to settle and results in an aesthetic that’s inexplicably calming.

Displacement ends with a visually rich meta-narrative about how the author-protagonist, with the help of her mother, went about the extensive research behind this book. Her grandmother, Ernestina, a survivor of the incarceration camps, died years before the author was born, which left a gap in Kiku’s understanding of her famliy history. In the concluding chapter, we see Kiku discovering family mementos (including one that she had encountered in her travels back into the past), letters, photographs, and recently declassified archival documents. The metaness of the chapter provides the reader a glimpse into how Kiku pieces together bits of history from both personal and historical sources. It implicitly emphasizes the dual role of the author-protagonist in the graphic memoir genre and compels the reader to consider the genre-blending nature of Displacement.

(1) Although the commonly used term is “internment camps”, Hughes uses the term incarceration camps because she believes it is more accurate and that the former “is used by the government to pacify the real history of the camps.”

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply