“I’ve been involved in a number of cults both as a leader and a follower. You have more fun as a follower, but you make more money as a leader.“

Creed Bratton, The Office

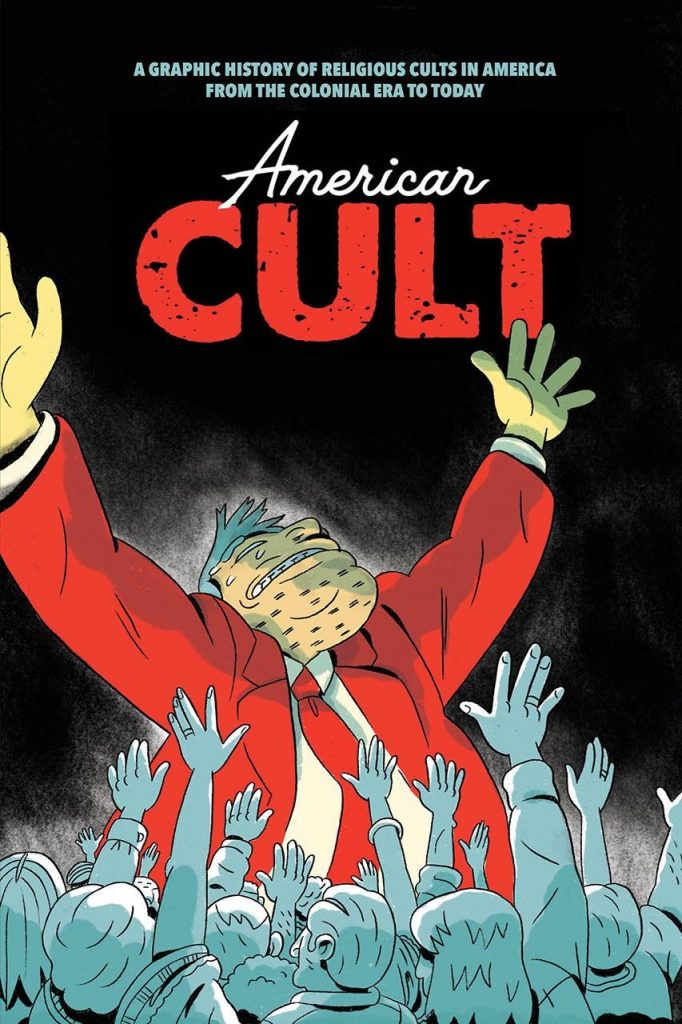

In considering the anthology American Cult, edited by Robyn Chapman, it is important to consider both words in its title. In her introduction, Chapman goes into great detail about what makes up a cult, talking about their totalitarian nature, family structure, and iconoclastic belief system. What was more interesting to me was the “American” part of all this. America was colonized in part for so-called “religious freedom,” which was a polite way of getting all of the weirdos out of England. Of course, religious freedom tends to last about as long as it takes for it to become the new establishment, which led to immediate fracturing.

The anthology emphasizes two themes in particular that have resonated throughout American history, from the 17th century until now. The first is a kind of utopian, iconoclastic thinking. It’s part of that often virulent American individualism, where there’s always someone actively opposing the mainstream, steady-state belief system. The second is good old American grifting. While most cults at least have an ideological set of underpinnings, one thing the anthology repeatedly details is how it didn’t take long for cult leaders to take advantage of their situations, including sex, money, and power. And why not? They were all chosen/anointed/called and/or given special wisdom. America’s tantalizing nature as a place where the intrepid few could always strike out and settle new territory, even in the present day, is part of the grift.

Chapman’s decision to sequence the stories in chronological order further cements this impression of history repeating itself. What makes this an interesting book to read is that the contributing artists use widely varying approaches. Some take a heavily researched historical approach. Others try to bring those figures to life by inserting fictive elements like dialog. Some of the more interesting stories are told directly from the point of view of someone who had been in the cult or were written by an actual former cult member. Taken as a whole, certain details emerge. Cults generally form around a single, highly charismatic leader. That leader draws followers because he’s full of iconoclastic ideas and creates what amounts to be a found family around these ideas. Almost inevitably, the leader becomes drunk with power and starts abusing it through violence, greed, and sexual predation. Virtually every cult had a number of good ideas that were often ahead of their time, but they eventually became warped thanks to this rigid hierarchy. The results were often tragic.

The stories that stood out in the anthology either have a distinctive visual approach, an insider perspective, or an especially pointed authorial viewpoint that represent vast amounts of research. None of the stories have all three. American Cult opens with Steve Teare’s account of Johannes Kelpius and his followers in the 17th century. Of all the cults discussed in the book, this was perhaps the most benign. His followers believed that “nature and God were one,” an idea that’s commonplace today (especially in Eastern religions), but was forbidden back then. Despite being an apocalyptic cult, when their predicted day of doom came and went, they didn’t abandon their beliefs. Indeed, Kelpius influenced the Quakers and there’s still a Kelpius Society in existence today. In many ways, it represents the utopian spirit of religious freedom in America: peaceful, kind, and seeking harmony with nature. It would be the exception to the rule.

Emi Gennis’s account of the Oneida utopian colony would be a more accurate model for future cults. Gennis’ dynamic layouts and explicit focus on the carnal nature of this free love cult makes it one of the stand-out entries in the anthology from a storytelling perspective. It also speaks of another commonality in cults: beginning with a good idea (here, founder John Humphrey Noyes’ belief in the equality of the sexes) and taking it way too far (his belief that any kind of family or love relationship was forbidden). Focusing on its effect on his niece and lover Tirzah, it’s the quintessential story of a man who believes that God is talking to him directly. Even the looniest of ideas, once reified, becomes dangerous doctrine, and that’s what happened in Oneida.

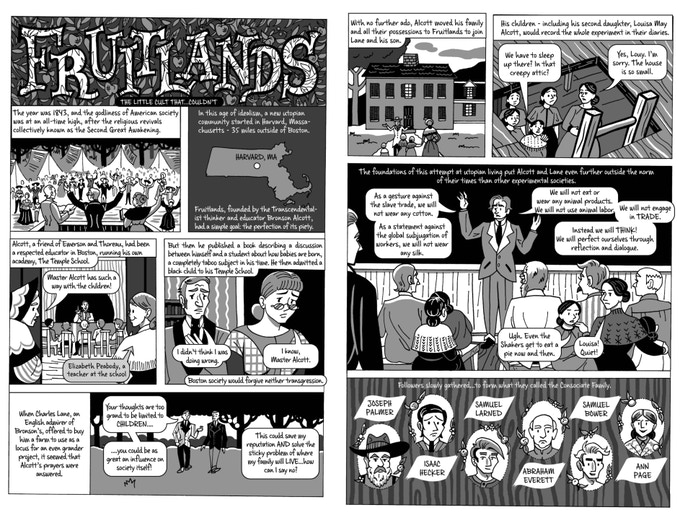

Of course, as Bronson Alcott proved, if you don’t keep your followers’ bellies fed, you aren’t going to have followers for very long. A good cult leader either keeps his followers fed or disorients them enough to forget about eating (like Charles Manson, who’s also in the book). Alcott, a teacher and Transcendentalist, was vegan, anti-capitalist, and anti-slavery. Of course, his general plan for keeping everyone fed was a hand-waving “God will provide!” Ellen Lindner did this entry, and her knack for drawing period figures is useful in telling the story of this daydreaming loser who naturally put most of the burden of labor on women.

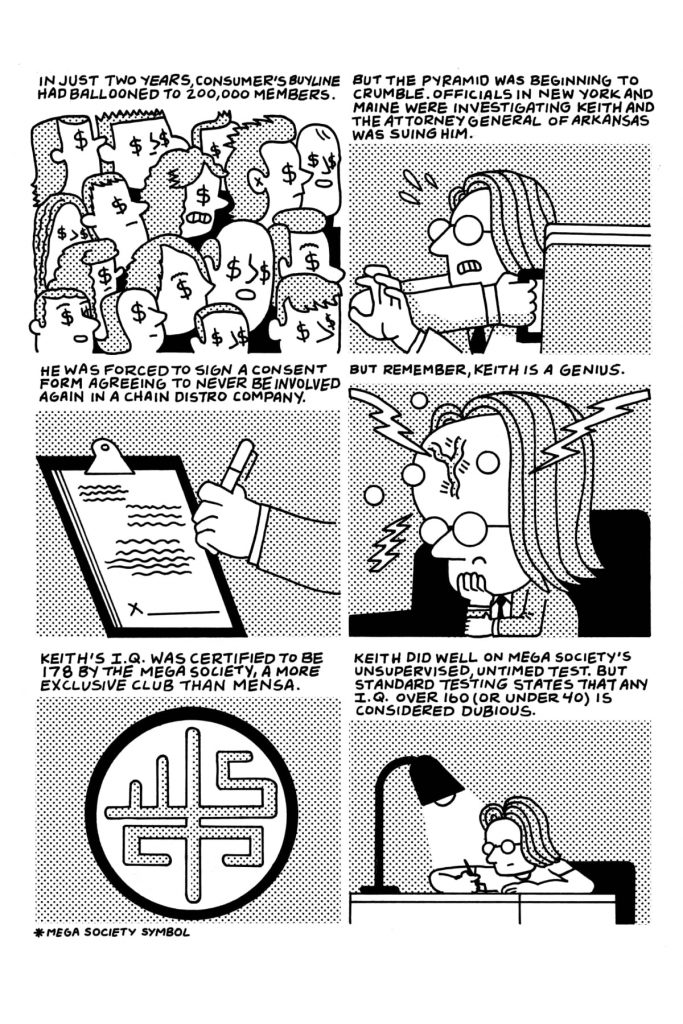

Gennis and Lindner provide two of the more visually interesting stories in American Cult, most of the rest are rather conventional in terms of visual storytelling. There are a few exceptions. Rosa Colon Guerra’s entry about the notorious Children Of God cult frames the story in the same way the founder, Dave Berg, used comics with his followers to normalize having sex with children, with friendly drawings and attractive fonts. Jim Rugg’s story about the Manson family is done in his gritty 70s-era style. Box Brown writes about Keith “Vanguard” Raniere’s sex and multi-level marketing cult NXIVM in his usual, abstracted/cartoony style, and it works in reducing this ridiculous figure to being a cartoon. The rest are fairly naturalistic in terms of their figures and familiar in terms of layouts. The exception is Andrew Greenstone’s story about the Source, and his grotesque, exaggerated big-nosed figures do not gel at all with the dark source material about yet another sex cult.

The three stories from a personal point of view all stand out. J.T. Yost adapts a young woman’s story about being kicked out of the infamous Westboro Baptist Church, and it’s fascinating because of how differently they operate from other cults. It still centers around a singular personality (Fred Phelps, whose virulent homophobia, it is hinted, may have arisen due to an incident in his youth). Its beliefs are iconoclastic, as their embrace of hatred as an ideology turns off even the most extreme of right-wing Evangelical types. It operates as a family unit, as the girl talks about the way they were welcomed by the other church members when they moved to join them in Kansas. She also describes how the Phelps girls and other Westboro members her age befriended her. However, the sex and money grifts common to most cults didn’t interest Phelps, who wasn’t even trying to recruit new members. He was a hardcore Calvinist who believed in predestination; his sole purpose was essentially to tell everyone else how sinful they were. When the girl started to question aspects of the church and started to see boys, the pain of being tossed out of this tight-knit group (and her own family) was greater than the questions she had about it. Yost’s rubbery but naturalistic style is appropriate for someone as over-the-top as Phelps.

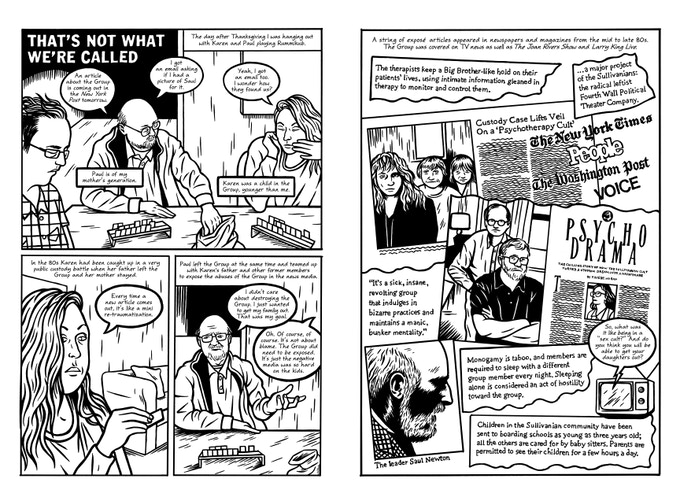

Lonnie Mann’s personal account of how he considers Orthodox Judaism to be a cult is certainly damning, especially as a gay man. While his personal experience is powerful, I found myself wishing that he had spent some time exploring the history of how Orthodox Judaism became so unbelievably oppressive to its members. The art serves its purpose but is far less polished than the rest of the book; it is also less a story than a rant that was a long time in coming. Jesse Lambert takes a more measured approach in discussing The Group, also known as the Sullivanians, a psychotherapy, polyamorous sex cult in New York. He talks about the weirdness of growing up in a communal setting and the awkwardness surrounding bringing people over. The story is set around a game night with two other former members and how all of them are continuing to try to process what they experienced. Lambert’s fluid line eschews visual exaggeration, helping to establish a tone that’s less angry and more bewildered.

The most interesting pieces overall in American Cult are by Ryan Carey (full disclosure: Ryan Carey is a fellow member of the Fieldmouse Press board and a founder of SOLRAD) & Mike Freiheit; Robyn Chapman, and Ben Passmore. Carey not only has the most thoroughly researched piece in American Cult, on the horrific Jonestown massacre and the People’s Temple, he legitimately brings new research and scholarship to the subject. In particular, he challenges the “drinking the Kool-Aid” narrative of a group of brainwashed believers and instead provides evidence for Jim Jones essentially enslaving a population of mostly people of color in order to carry out his latest grift. Freiheit’s gritty art leans too heavily on effects like zip-a-tone, rendering it muddy and occasionally difficult to read, though.

Chapman’s story about the Heaven’s Gate cult is particularly thoughtful because while they gained a lot of notoriety for their suicide pact concerning the arrival of the Hale-Bopp comet, the cult itself eschewed the kind of money, power, and sex normally associated with cults. If anything, it resembled the original cult of Christianity, where Jesus called people away from their everyday lives in order to follow him. While cult members were required to leave their old lives behind, there was a sense that they were happy to do so. The cult, like many belief systems, filled a certain inner lack and provided a kind of order. Unlike Jonestown, they seemed to die happy, even if their reasons for doing so were totally delusional.

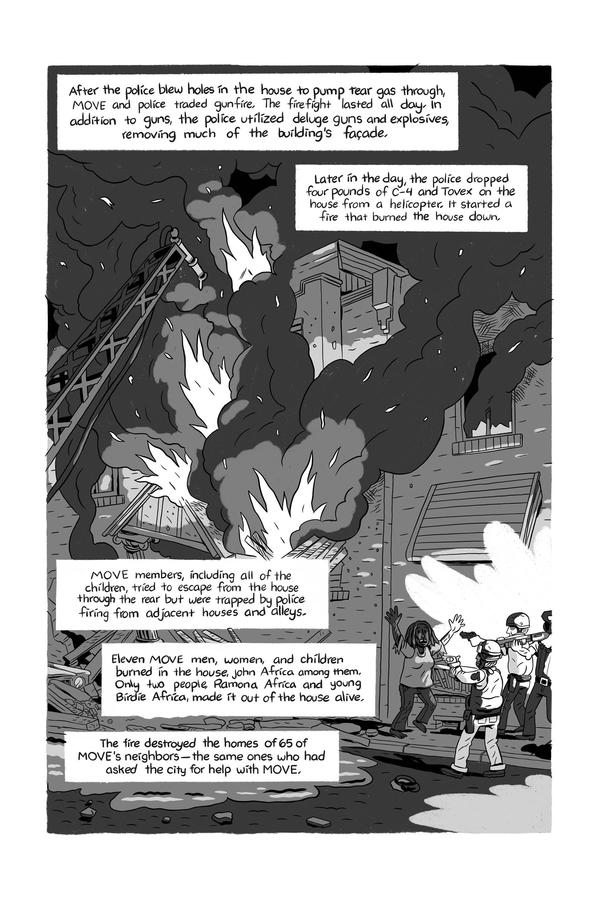

Passmore’s piece on the rise and fall of the MOVE cult in Philadelphia combines his thorough research, compelling storytelling style, and point of view as an activist fascinated with Black nationalist/militant movements. Its founder, John Africa, was the quintessential cult leader. He was a beloved character in a bohemian neighborhood, gentle and loving. As Passmore notes, most of MOVE’s members were Black but John Africa eschewed identity politics. His cult was vegetarian and valued life, but it also stockpiled weapons like a militia. Passmore provides a lot of perspective on MOVE’s clashes with the racist police force, noting that their neighbors sided with the police because MOVE was a terrible neighbor. Passmore also documents how John Africa responded to his members disagreeing with him by having them beaten. In a final confrontation, the police dropped C4 on their headquarters and started a fire that not only killed most of MOVE’s members, it also destroyed the house of the neighbors who had begged them for help.

Passmore looks at MOVE differently than most of the other artists in American Cult. He tries to think of things from their perspective, and how cults are often a reaction against various forms of oppression. Sometimes that was religious oppression, but it was also state oppression, family oppression, and oppression by any kind of established power structure. Passmore’s last line rings true for the entire collection:

“To me, MOVE is an example of how no strategy or set of politics is inherently revolutionary if it empowers an oppressive individual or inner circle over their peers. We have to be careful. This is America, and in America we have a history of prophets who will lead us from one cage to another.”

Those prophets might be doing it for a fast buck, or to have coercive sex, or to work out some kind of trauma and unleash it on the world. They might be narcissists or schizophrenics. They might even have good intentions. American Cult illustrates that, almost all of the time, what appears to be the path to enlightenment is just a different kind of road to ruin.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply