In the immortal words of the equally-immortal Marlon Brando in Richard Donner’s fairly immortal (for many at any rate) Superman: The Movie, “you will see my life through your eyes, as your life will be seen through mine — the son becomes the father and the father, well, the son.” My question — does this observation have a one-generation limit?

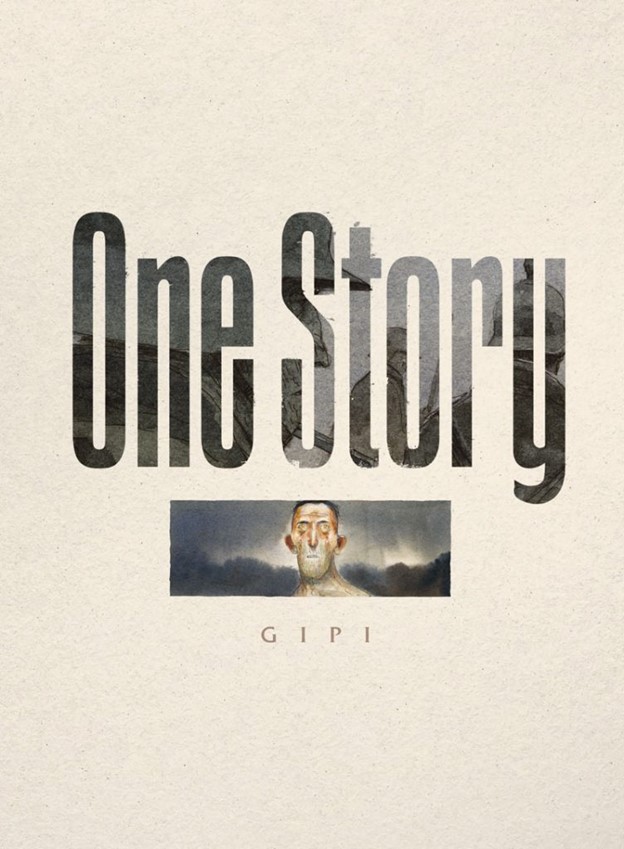

If legendary Italian cartoonist Gipi is to be believed, it most certainly doesn’t — but in his new graphic novel One Story (Fantagraphics, 2020, translated by Jamie Richards; originally published as Unastoria by Coconino Press in 2015) he also posits that the phenomenon of history repeating itself isn’t necessarily the warm and sentimental truism expressed by Brando’s Jor-El. In fact, it can be downright crippling.

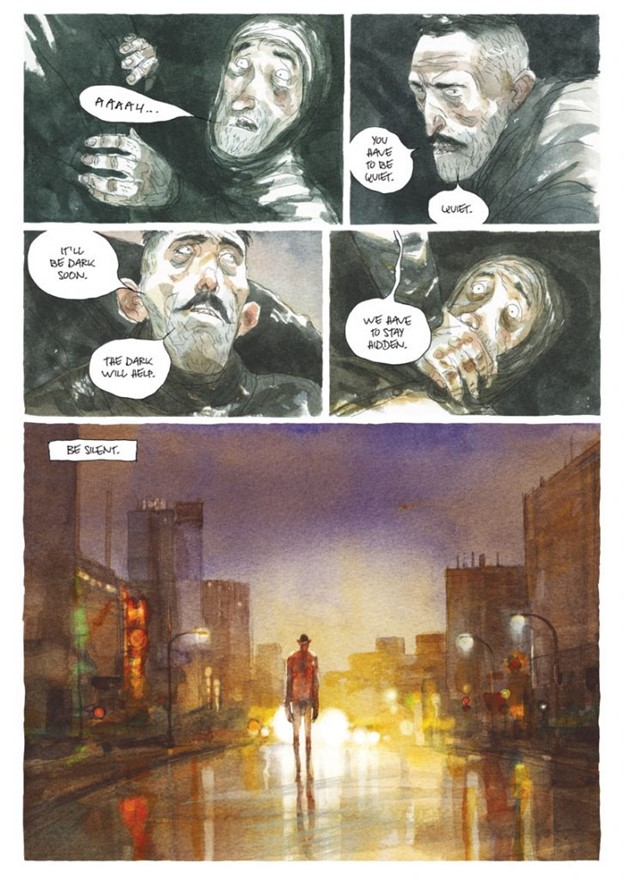

Gipi’s protagonist for this tale of familial recurrence is one Silvano Landi, a successful writer who finds himself confined to a psychiatric ward following a breakdown ostensibly engendered by the dissolution of his marriage and subsequent estrangement from his daughter, but the roots go deeper than that — an exploration of just how deep, though, is the vein this book seeks to mine, and the conduit by which this is expressed is the WWI combat journal kept by Silvano’s grandfather, Mauro, a soldier in the trenches who lived the old adage that “war is hell” firsthand. There are times when it seems that Silvano’s obsession with this diary may have been the triggering event that drove his wife and daughter away, and others where one gets the impression that his detailed examination of its every line may have begun after they made their exit, but, in the end, the exact timeframe is of secondary (at best) concern to readers — what’s more important are the parallels to be drawn between the two stories that form the titular “one story.”

To that end, Gipi’s artistic skills are both his greatest ally and the truest metaphorical arrow in his quiver — where his dialogue can veer toward the stilted and overly-obvious, the expressionistic and intuitive transitions he makes from black and white linework to richly evocative painted watercolors to more traditional comics illustration complete with computer coloring lend his dual narratives the connective tissue that the script frankly lacks. Gipi’s art adds to the proceedings a lyrical, at times even poetic, quality that, at its best, transcends the page and goes straight to the heart.

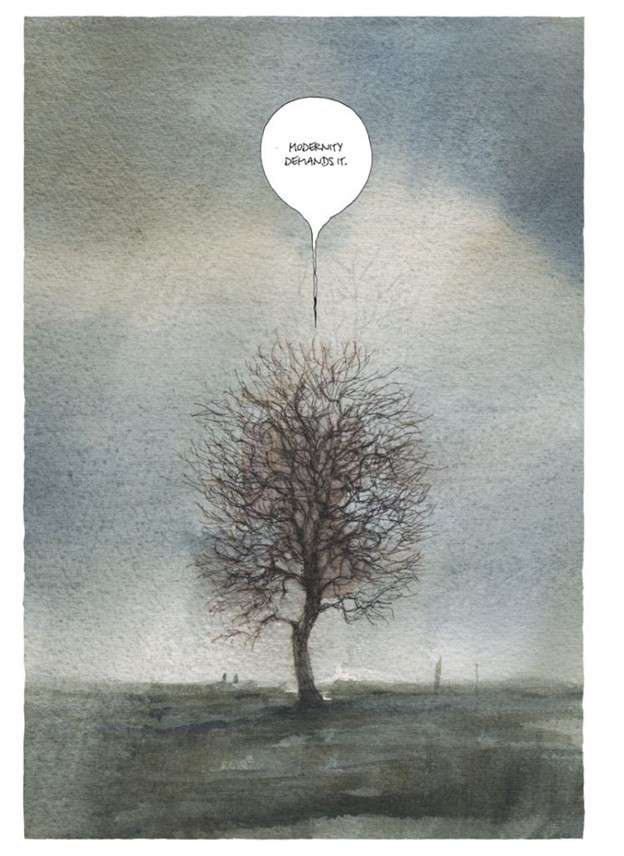

Indeed, Gipi creates a number of images herein that aren’t just worth spending time with, but getting downright lost in, and these sparsely-scripted and/or completely silent pages say a lot more with pictures than they ever could with words — and the cartoonist himself seems keenly aware of this, relying on his artistry alone to transform his dueling narratives into parallel ones and then, finally, into a unified whole. It’s as ambitious a task as it sounds, and it requires a deft touch to say the least. And there are times when a reader can be forgiven for thinking Gipi’s just not going to be able to pull it off, such as when the senior Landi is called upon to quell his fears and muster up a profound sense of control and calm against all odds in order to survive, while at the “same time,” if you’ll forgive the expression, his descendant’s situation is entirely the result of a loss of those very qualities in his own self.

Still, as stated at the outset, this is ultimately a single-destination narrative that runs on two tracks, and how successful Gipi is at tying them together depends largely on how literal a reader you happen to be. If you go with the flow that the cartoonist establishes visually, then the dead tree symbolism that he uses as a unifying trope will most definitely register with you and feel very much like the culmination it’s intended as. If the book’s visual lyricism hasn’t registered with you, though, then the great unifying moment, as well as the symbol used to express it, will not only come off as decidedly less than great, it may fall flat at best — or come off as hackneyed and forced at worst. I can even see how subsequent readings of the same book will yield different results — so it’s not just a case of your mileage may vary, it’s that the book’s mileage may vary depending on your own state of mind at the time you read it.

Still, isn’t that the case with most challenging works of art in any medium? And while Gipi’s ultimate conclusion about history repeating itself isn’t anything especially new, showing how it does so within two entirely different situations, two entirely different lives, and how strength and wisdom can be derived in direct, rather than second-hand, fashion from our ancestors is a unique — if occasionally oblique — method of exploring a tried-and-true theme. Even the most generous reading of the book may not find it to achieve the transcendence and catharsis that Gipi pretty clearly seems to be aiming for, but his art both breathes life into his narratives and gives them room to breathe, so as counter-intuitive as it may sound, I think that by missing the mark he was going for, he achieves something far more human and resonant instead.

As is probably clear by this point, I’m in no way prepared to say that One Story is a flawless work. What the narrative does so well, though, is weave its flaws into its storytelling DNA and combine them with truly extraordinary visuals to create something that’s as memorable, multi-faceted, and quietly momentous as life itself — two lives, even.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply