Beginning with a hauntingly beautiful elegy for the late actor River Phoenix and concluding with a harrowing analysis of the infamous episode of Geraldo where the host’s nose was broken by brawling neo-Nazi skinhead thugs (an incident that I would classify as the only favor Nazis ever did for the rest of us) would perhaps lead one to conclude that Mannie Murphy’s debut full-length graphic novel I Never Promised You A Rose Garden (Fantagraphics, 2021) was a sprawling examination of disparate pop culture threads — and so it is, but only in service of its larger aim. And trust me when I say that “larger aim” is a very large one indeed.

Just to be clear: Murphy clearly has a love for their hometown of Portland, but that doesn’t preclude the author from taking honest stock of the city’s racist origins, history, and present — and, indeed, Murphy is perhaps understandably pessimistic about its future. And while this sprawling narrative touches upon everything from the genocidal evils perpetrated on the Native population by white settlers along the Oregon Trail, to the 1948 flood that destroyed the majority-black community of Vanport and the subsequent segregationist “red-lining” of its former residents into Portland’s Albina district, to the infamous hate-crime murder of African immigrant Mulugeta Seraw, to the so-called “Bundy Ranch standoff” of recent vintage, there is no doubt that this story is as much Murphy’s own as it is that of their city and its surrounding environs. And yes, I realize how counter-intuitive, perhaps even inherently contradictory, that sounds.

Still, from page one onward, there’s never any doubt that this is a singular and authentic journey, a documentation of one person’s attempts to come to terms with the shameful history of the place they call home. As such, it’s painfully honest, but also melancholic — Murphy’s not out to shame the residents of present-day Portland, nor the readership in general, so much as to make people aware of the fact that history is written in blood, and that far too many debts remain unpaid. To that end, then, this is a localized, microcosmic representation of a larger history — that of the United States itself and, indeed, all “frontier” countries in general.

Surprisingly, though, there’s nothing dry, academic, or even especially “preachy” about it. Murphy’s prose is unwaveringly fluid, disarmingly intimate, and, at times, even borders on the poetic. This effect is amplified by the fact that the entire book is hand-written in cursive, with errors and their on-the-fly corrections left in place, the resultant aesthetic being far more akin to that of a personal illustrated journal than to that of a traditional “comic book.” Which brings us to the art —

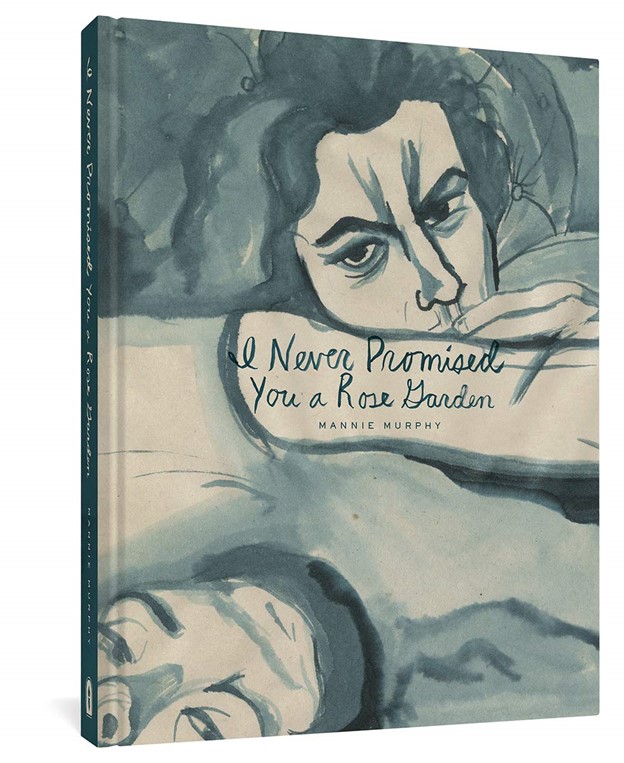

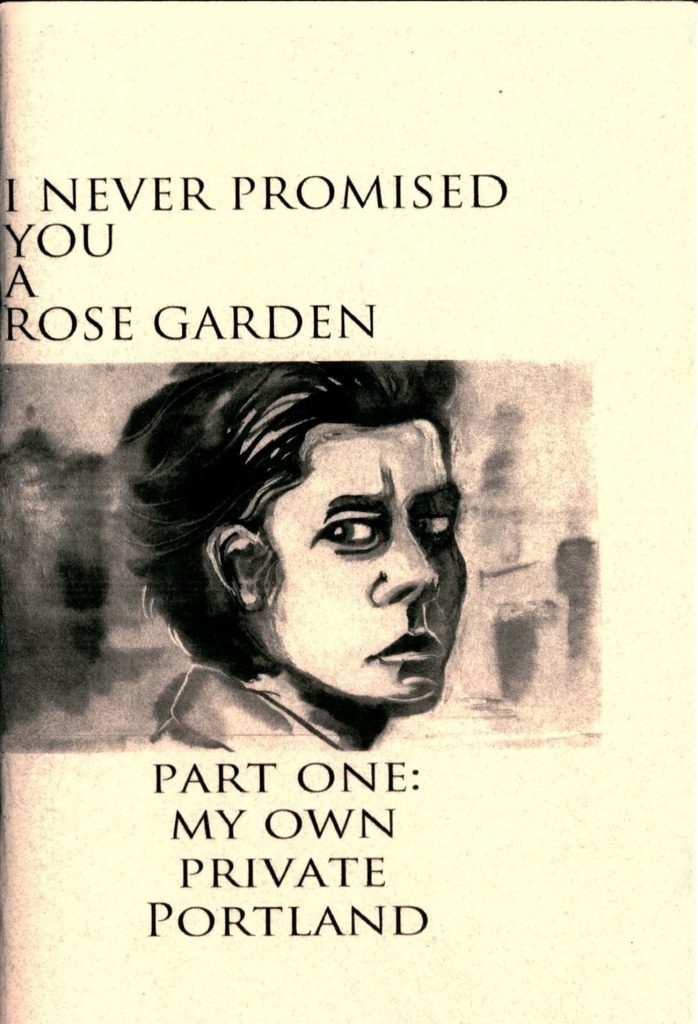

This project began life as a series of self-published ‘zines (the cover to the first of which is shown above), and while the Xeroxed periodical has its charms as a format, it also has its limitations, the most glaring being that small-scale B&W reproductions simply couldn’t do Murphy’s lush, immersive, and thoroughly absorbing art justice. Now, presented full-sized and awash in moody blue-green watercolor hues, the pages absolutely sing — and while their song is decidedly plaintive, it’s also inarguably haunting. Murphy’s figures are often presented as idealized ghosts, and they stare back at us wistfully, knowingly, in that “see into your soul” sort of way. Imperfections abound, but again, as with the (literal) writing, they add to the work rather than detract from it.

Perhaps the most intimate feature of this book, though, is the very “connective tissue” that binds all these elements together — this is a narrative very much rooted in Murphy’s own formative years as a genderqueer teen and young adult, and, as such, it’s not only doubtful that any other author could weave a troubling-but-gorgeous tapestry from the wholecloth of a youthful crush on River Phoenix, a taboo fascination with gay Nazi street hustler Ken “Death” Mieske, a detailed knowledge of the notorious Whitman Massacre of 1847, and first-hand experiences with Portland’s brutally racist police department (among other elements), it’s flat-out impossible. As stated before, this is Murphy’s own story every bit as much as it is their city’s.

Truth be told, I’m not even sure that previous comics writers and/or artists who have spent much of their creative careers grappling with issues related to their home turf have attempted something along these lines — Harvey Pekar could tell you everything you’d ever care to know about Cleveland, for instance, but seldom broached the subject of how its past made him feel. One could fairly argue that Alan Moore’s Voice Of The Fire and Jerusalem attempted something at least similar to what Murphy is exploring here, but those are prose novels (the latter being an absolute monster in terms of its length) that are every bit as concerned (if not moreso) with the esoteric terrain of Northampton, England as they are its physical, cultural, and social landscapes. In the annals of graphic literature, then, this book could very well be precisely what it reads like — something unique, original, and absolutely singular in terms of its goals and methodology.

It’s both fair from a critical standpoint and true from a historical one, then, to say that I Never Promised You A Rose Garden is an utterly remarkable work. I suppose it would have to be in order to successfully incorporate everyone from William Burroughs to the Red Hot Chili Peppers to Kurt Cobain to Keanu Reeves to Cliven Bundy to former KKK Grand Wizard Tom Metzger to Gus Van Sant to, yes, even Geraldo fucking Rivera — and on that note, it may be worth noting that Geraldo and the Nazis who broke his nose all ended up on the same side of the political fence as enthusiastic supporters of disgraced former president Donald Trump. If you’re wondering how the hell we could end up living in a world where such a thing was even possible, this book charts that path in achingly human terms and shows that, if anything, it was probably inevitable all along — but Murphy makes much more than a case for the idea that the currently depressing and alarming white nationalist resurgence is no mere blip on history’s radar screen. They also make a strong case for this being the most affecting, inspired, and important comics release of 2021 to date.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply