Put yourself into the following hypothetical scenario: what if, instead of the barren ball of dusty rock that the Earth has for a moon, we had a strange but gorgeous water world? To help you think about the prospects, let’s say that this hypothetical water world is completely habitable, given the appropriate infrastructure — it has a breathable atmosphere, a gravity similar to that on Earth, and it can support life. How would that change the way we think about the escalating climate crisis we suffer here on Earth? Lane Milburn drops readers into such a scenario in his latest comic, Lure, published by Fantagraphics earlier this year, and the result is a slow-burning sci-fi climate thriller that has a whole lot of questions, but not a lot of answers.

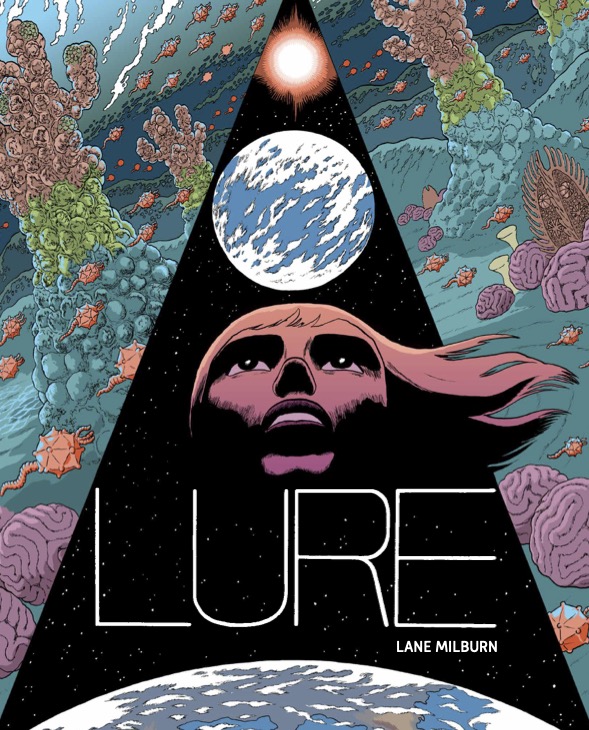

Lane Milburn is probably best known for his work on Twelve Gems, published by Fantagraphics in 2014, and for his work with Vice.com, where the seed that would become this book would sprout. Milburn’s previous work was full of camp, verve, and homages to the science fiction and high fantasy of the 1930s and 1940s, but Lure is much more a story of our time. It concerns itself with a science fiction conceit, yes — the question of “what would life be like on Earth if our moon was actually a gorgeous habitable water world called Lure” is the core of the book — but the questions that Milburn asks are decidedly 21st century, concerning the power inequities between the wealthy and the working class, the ravages of climate change, and the position of the artist in capitalist systems and extractive economies.

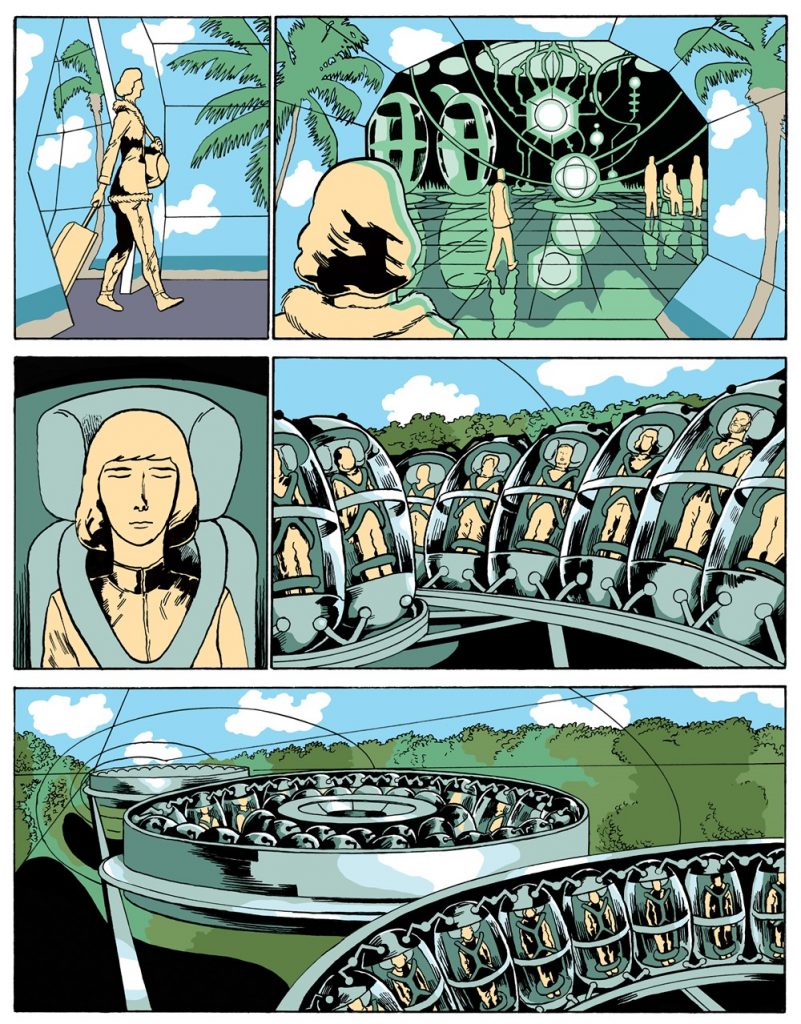

The story starts with Jo, a frustrated working-class artist, who is preparing for launch to Lure for work. In a series of flashbacks and conversations, we see how Jo got to this place in her life: she attempts and fails to get accepted for a major travel grant and her art practice is stagnant. Her former romantic partner leaves her to move west to work for his dad, leaving her unattached and looking for something new. Even though she doesn’t like the prospect, she turns to “working for the man” after she can’t make things stick. At P, an oddly named mega-corp, she serves as a cog in the corporate machinery. Her work as a hologram artist sells probiotics, bowel cleanses, and bath products. To get to Lure, she applied to be an artist in residence for the company’s upcoming massive economic summit and gets accepted. Despite her insistence that P isn’t her style, we see her getting on a space shuttle on P’s dime, and honestly, she looks pretty happy about it.

What Jo finds on Lure is a 24/7 paradise. Her fellow artists, Rachel and Chris, both come from different backgrounds, and the team is tasked with creating a remarkable hologram show for the economic summit which is only a month away. Herein lies one of the first strengths of Lure; Milburn’s character building throughout the comic feels natural and unforced, and the characters get caught up in a variety of emotional and ideological conflicts that intersect smartly with the questions Milburn is posing in the book. As Jo, Rachel, and Chris spend more and more time at the Lure resort, the cracks in the paint start to show. The lives of the workers at the resort seem just as drab as the lives of laborers on Earth’s surface, and there’s a line between the haves and the have-nots that is only partially masked by the artists’ all-access pass. The narrative ratchets up the tension when Jo and Rachel find evidence of a massive project which will upend the future of Lure and which paints their current work as artists for P’s economic summit in a completely different light. The two pledge to do something about it, leading to a denouement that leaves readers guessing until the final page.

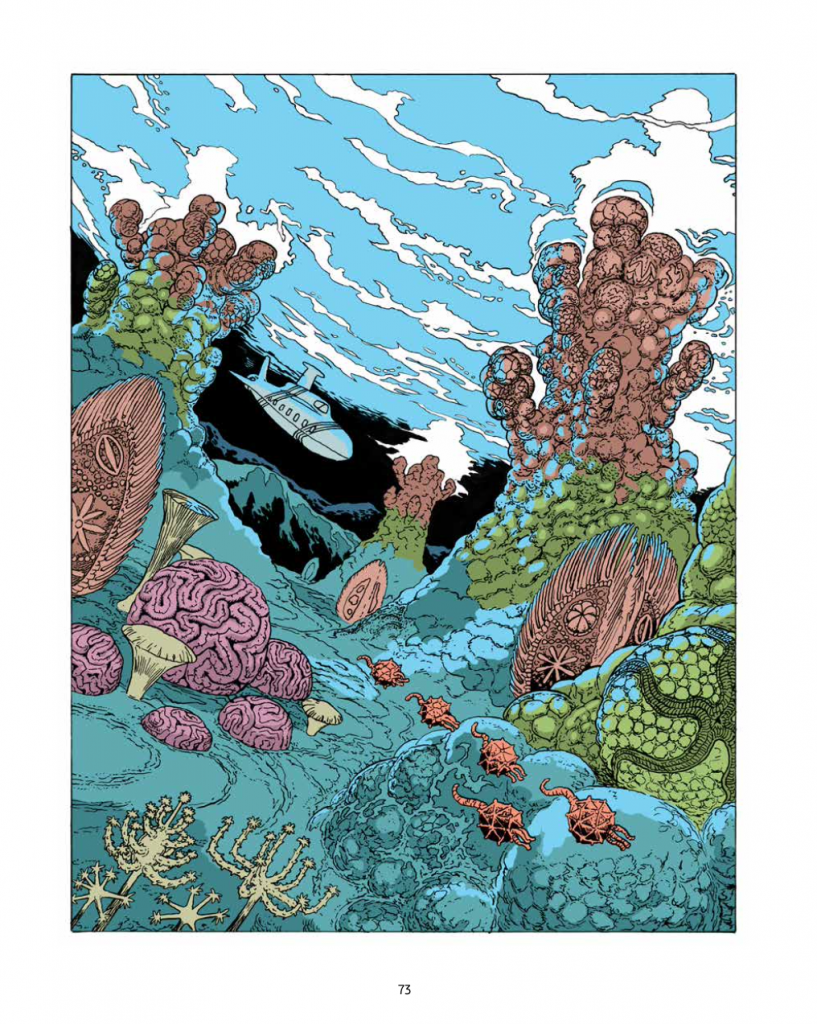

One of the themes that Milburn spends much of the book interrogating is the symbiosis between Western empire and culture. Colonialism repeatedly uses art to justify its empire-building, to justify its conquest and subjugation. The history of American landscape painting has long been linked to the goals of expansionists during manifest destiny, and photography was a key tool used as a part of the “civilizing mission” of the European Christian church in Sub-Saharan Africa. These images have a specific perspective, a specific purpose, and the art that the creators make in Lure is no exception. Jo, Rachel, and Chris, who are making the hologram show for the Lure economic summit, are brought on-planet, all expenses paid, in a way that is reminiscent of the patronage systems of art in the Middle Ages. They create something that Milburn renders as both unique and beautiful; dancing figures that push and pull building blocks that eventually create the planet of Lure. “You are the worldbuilders, and what you are building is Good,” says this display. Lure, the planet, is not a living and breathing thing — it is a place on which to build, an asset to exploit, a frontier to be conquered. Assured of their significance and power, an elite crowd of politicians and one-percenters is presented with that same old colonial message with a new coat of shellac. While there aren’t any native peoples to displace, there is a pristine landscape filled with alien creatures, and the negative effects that result from the incursion of humans into their world are made clear throughout the book.

The tension between the current capitalist milieu and a more egalitarian future is one that seems to loom over Lure, and Milburn uses linkages between his characters and real-world artists to help solidify and sometimes complicate that tension. Artists like Cecily Brown and Alberto Giacometti are cited in Lure, and these artists are well known for the tension inherent in their work (be it the tension between material and subject, or the constant stripping down and rebuilding of the art they make). These little references, small components of a much larger narrative, give thematic resonance and depth to Lure. Milburn includes the art history of our world, and its place in society, as an internal sounding board for his own work in this comic, and Milburn is constantly connecting his group of characters to the art movements and art practices of (real) Earth.

This thematic tension between ideals and action is largely the hinge on which much of the drama of Lure rotates. Jo consistently says that P isn’t “her style” and has plenty of outrage about their desired business goals when they come to light, but she’s still drawing a paycheck, still polluting a pristine world for her own selfish ends. “What is the place of the artist in a capitalist society?” Milburn asks, and, like many of the questions asked in the book, this one doesn’t have a clear answer. There’s no ethical consumption under capitalism, and Milburn seems to indicate that there’s no ethical production of art under capitalist structures either. Milburn seems to indicate that art is a foundational component of resistance to exploitative forces, but it can just as easily be used as a tool of empire-building and extraction economies. In Lure, it is the final holographic artwork that is positioned as the only thing that can reveal the truth, but, in a stroke of storytelling genius, Milburn’s chief spoiler is also an artist.

One of the things I find myself reconsidering after a few reads of Lure is Milburn’s use of a deity figure who creates Lure from the molten beginnings of the Earth. Milburn’s use of this character is sparse, but she adds a sort of allegorical weight to the story, and at times makes hazy what should look solid or real. While there is much left to the imagination (yet another question that Milburn doesn’t believe needs answering), this goddess figure seems to interact most with Chris, the odd man out of the group who slowly gets involved with VR gaming and spends less and less of his time topside. What is real, and what is under the control of individuals, this goddess asks — is everything destiny, and outside our control?

Now, I love a good theme as much as the next critic, but I also love the way that Lure looks. Milburn has changed his style somewhat, in a way that is clearly influenced by the work of Mœbius, but he brings a liveliness to his line and figure that I often find missing in the work of the French master. Milburn renders Lure with beautiful blues and greens, except for its flora and fauna, which sport a variety of vibrant colors. In contrast, Milburn uses differing intensities of ochre to render his human characters, a choice that acts as a stark contrast to the new world they work and play on. These coloring choices emphasize the alien quality of Lure and the unbelonging of the people on it. This is especially clear in underwater scenes, where vacationers dive around the massive corals, or when diners eat in a restaurant surrounded by water on three sides — in these scenes, the creatures that live on Lure look like animals of Earth’s distant past, or perhaps cells under a microscope, so even in the detail of the planet, Milburn is considering this big idea of “going back to the start.” It is these little details that exemplify the book, and the production is no exception — this is a gorgeous book, cover to cover, and Fantagraphics has done an excellent job with printing, design, and production.

If you haven’t caught on by this point, let me make my opinion crystal clear: I think Lure is perhaps one of the best long-form comics published this year. The ways in which it questions the status quo are fascinating, and, although the book doesn’t have a lot of perfect answers, it does ask a lot of great questions. From exploitation economies, wealth inequity, and the “escape mindset” that has driven billionaires like Elon Musk to send a Tesla into space, Milburn has his fingers on the proverbial pulse in this book. Lure is a prescient and critical evaluation of the driving questions of the 21st century, which make it a vital narrative for our time, and, besides all that, it’s a remarkably potent thriller. Ultimately, it’s a triumph of a comic, a work that leaves this critic with a conflicting sense of hope and dread. Can humanity overcome its past to achieve a greater future? Or, if given the chance, would we do it all again?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply