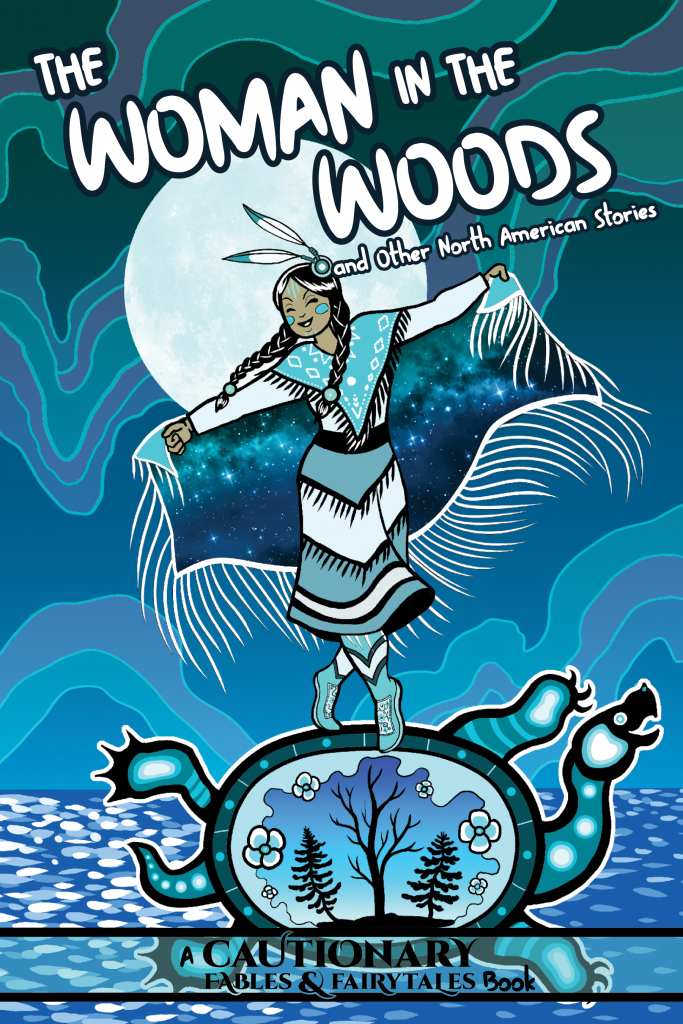

This is a book in the Iron Circus Comics: (ICC) series of books subtitled “A Cautionary Fables and Fairytales Book.” Each book focuses on a geographical/ cultural milieu. This series is for middle school readers and older.

A note about Iron Circus Comics: ICC was started by the very talented C. Spike Trotman in 2007. Originally it was a way for her to get her webcomic, Templar Arizona, into print. In the process, she mastered the Kickstarter model of financing. ICC has grown into a formidable indie publisher with material spanning from young adult (YA) to the line of body-positive, sex-positive, LGBTQ-friendly, consent-required adult titles under the imprint Smut Peddler.

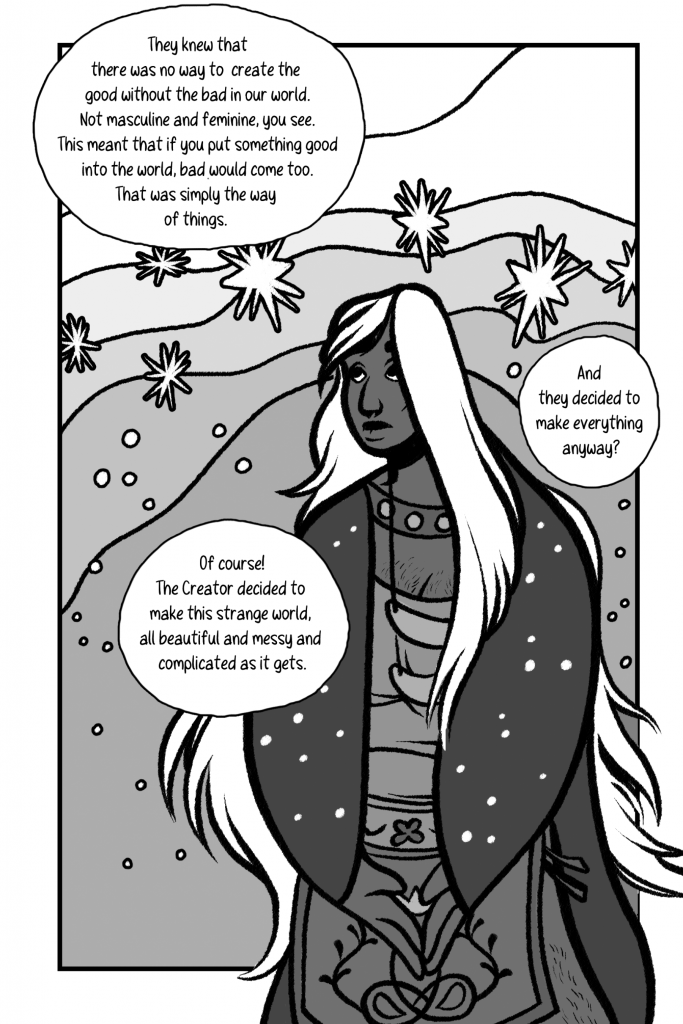

That LGBTQ-friendly stance permeates all of ICC’s books. Woman in The Woods and Other North American Stories is no exception. The opening story is an Odawa creation tale, fashioned by Elijah Forbes, called, As It Was Told To Me. The narrator tells the story to a young non-binary or trans person at a “Two-Spirit Circle.” While the term “two-spirit” is only about 30 years old, many Native American cultures have embraced the presence of gay, non-binary, and queer people for centuries – often to the chagrin or disgust of missionaries, anthropologists, and colonizing cultures, many of which have tried to erase or block that acceptance for the last three centuries. Fortunately, most tribes are reclaiming their heritage of acceptance and social roles for everyone. In this tale, the Creator is both male and female. When trying to decide if life should exist, The Creator calls on the masculine spirit who remains quiet on the subject. The feminine spirit, on the other hand, makes the case for life, acknowledging that there will be hardships as well as wonders for all that live. The art in this story really shines in the scenes depicting the tale. Despite the greyscale printing, they have vibrancy reminiscent of the work of psychedelic artists Peter Maxx or Wes Wilson.

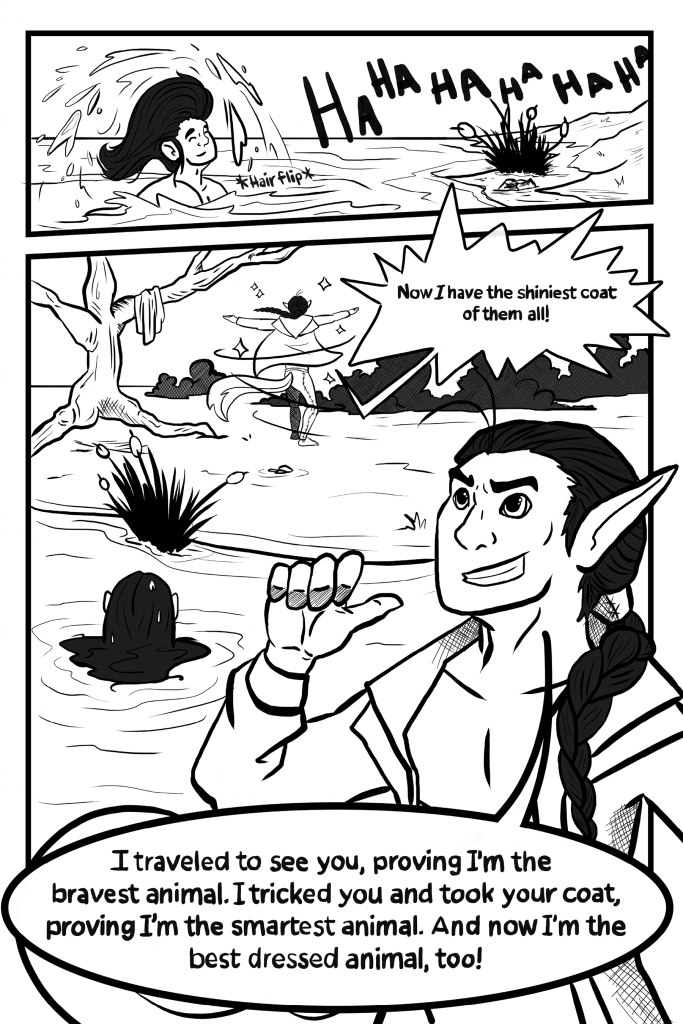

The next story is a trickster tale, Chokfi, written by Jordaan Arledge and drawn by Mekala Nava. Different animals are archetypical tricksters for different communities, the most common are Raven, Coyote, and Rabbit. In this case, the Chickasaw trickster, Chokfi, is a rabbit. I love trickster tales because they are always cautionary. Tricksters try to one-up, win through deception, or ignore the rules that come with a gift. In this story, all of the animals compete to be seen as having the most beautiful coat. Chokfi, with his long tail and soft fur, is acknowledged as very handsome, but Otter’s coat is praised above all others. Chokfi gets himself into trouble by trying to steal Otter’s coat and keep his own as well. I won’t spoil the fun, but in the end, Chokfi learns some hard lessons. The manga-inspired art is ideal for this story.

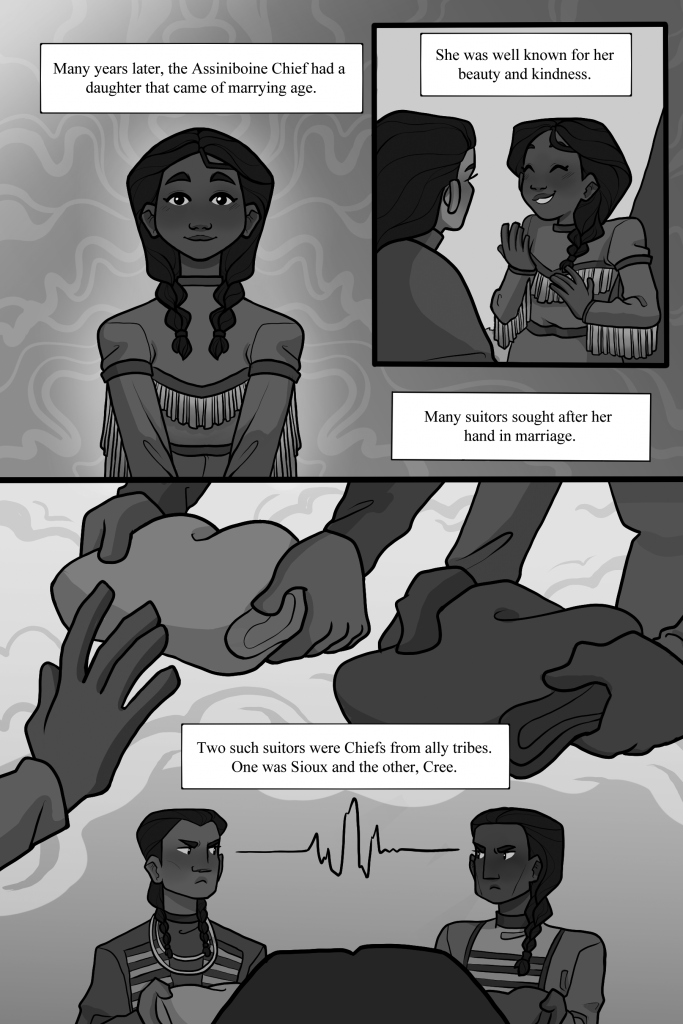

White Horse Plains, drawn by Rhael McGregor, with story consultant Sylvia Boyer, is set after the European invasion. It deals with the political alliances and land disputes of the Sioux, the Assiniboine, and the Cree. While the sale of guns to one side by white settlers does figure into the events, it is essentially a story of personal tragedy. The political and the personal intertwine and heartbreaking sorrow follows. A mythic figure arises from the loss and chaos. The layout, while not simplistic, makes the story easy to follow. The narration is in text blocks. Again, greyscale invokes a colorful world. I like the subtle nuances in clothing detail that delineates the tribal affiliation of the very emotive characters.

A Metis tale, The Rougarou is written by Maija Ambrose Plamondon with art by Milo Applejohn. Here, a girl and her younger brother go out to check the snares and traps they’ve set. The boy is uncomfortable with killing and runs off rather than kill a rabbit injured in the trap. When he meets a bear-sized creature that seems to be in distress, he befriends it. Eventually, his sister and father intervene. But rather than kill the creature, the father, like his son, takes pity. This encounter leads to revelations of things the children did not know about their own mother. This tale is another personal favorite because its lesson of compassion is universal, but the monster in the story is such a culturally specific creature.

Alice RL presents the Ojibwe tale Agonjin in the Water. As in Rougarou, the protagonist is a young person. This time, it is a girl well-steeped in her grandmother’s stories. Her people are facing a severe drought. She steals away in the night to see if she can find a mythical lake in the forest. When she finds it, she also meets the guardian spirit of the lake in both of its forms. One of my favorite moments is when she offers to trade stories for some of the water. The depiction of the telling of her tales is perfect. She and the spirit become friends, but the lack of water is forcing her people to look for a new home. Her newfound companion turns out to be a friend of her people, too.

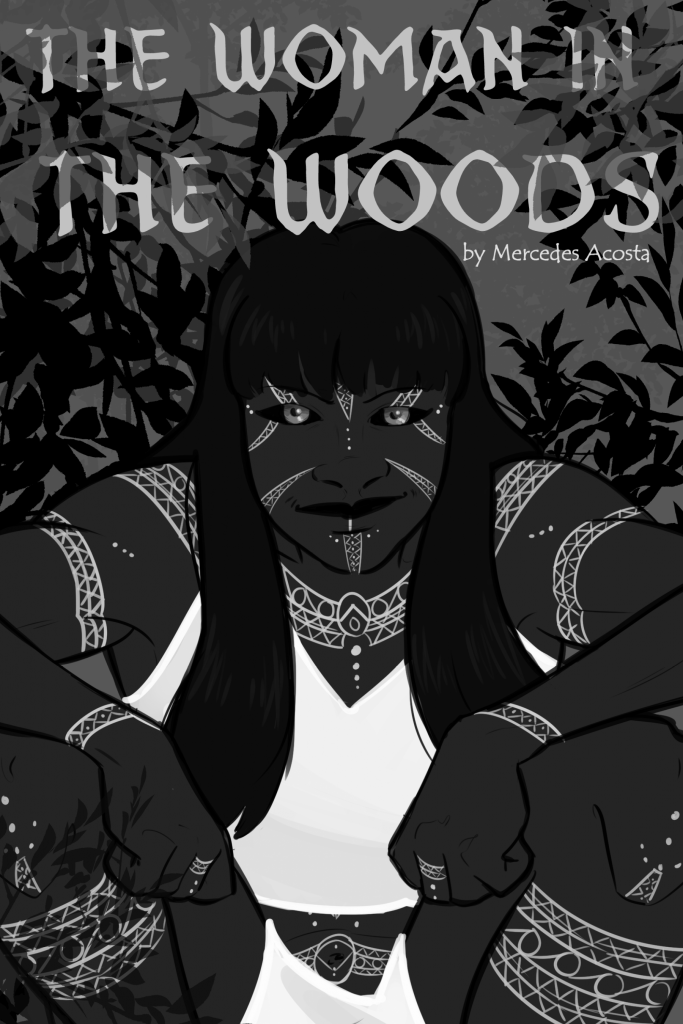

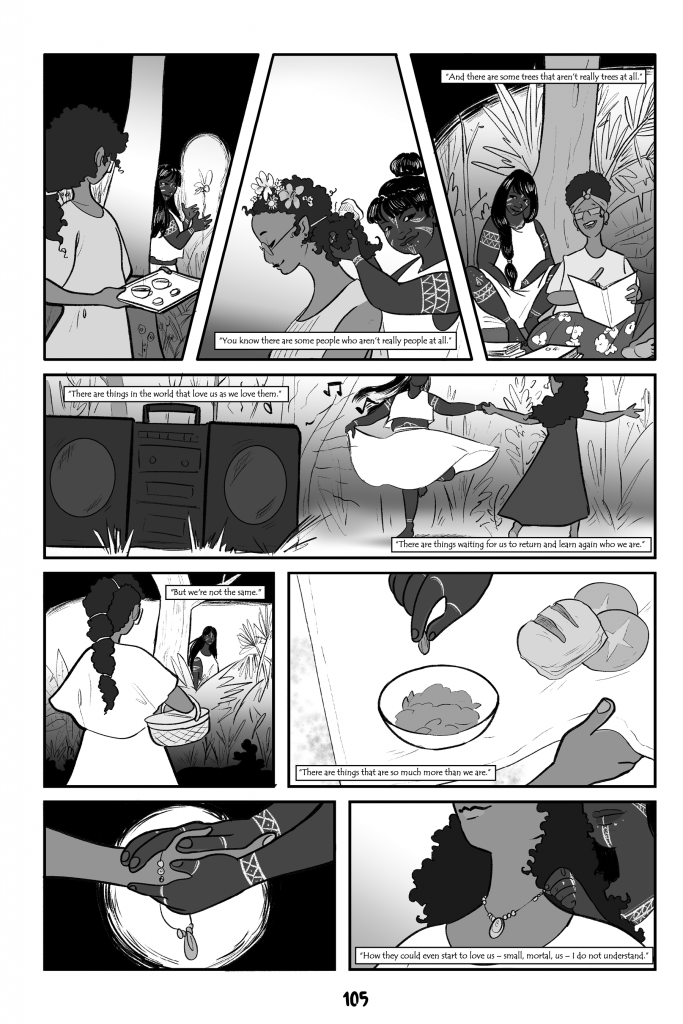

The title story, Woman in the Woods, is a Taino tale written by Mercedes Acosta. This tells of a different kind of relationship between a spirit creature in the woods and generations of women in a local family. The woods here are in subtropical South Florida. The people have the look and dress of the many cultures that have lived and mixed in the area.

Izzy Robert’s Navajo tale, Into the Darkness, is the most straightforward horror story. Two teen boys prove their bravery by spending the night in a van in the desert where shapeshifters are said to roam. Their encounter is filled with unspoken attraction as much as with supernatural horror. The settings are spare, like the desert itself. In horror film fashion, the art uses wide-open vistas, tight spaces, and noises from beyond the frame to create tension on a variety of levels. Aubrie Warner’s lettering adds to the creepiness.

The most lushly drawn tale is the last offering, By The Light of the Moon, a S’Kallam tale written by Jeffrey Veregge with art by Alina Pete. One of the other functions of mythic tales is to explain things in the physical world. This story takes on bioluminescence in the sea from the perspective of science and an ancient tale. Another element I enjoyed was that, in this story, the moon is cast as a male figure – not a common view in European-based mythologies.

The eight stories range widely in the best possible ways. They are drawn from different indigenous cultures spanning the North American continent. They are spread out in time, beginning with a creation story and including both historic and modern settings. The art styles work well together. They are distinct enough to place me in a new reality for each tale, but not jarringly different. I appreciate the two pages of short biographies of the contributors at the back. It is clear that people of indigenous background, often relating tales they grew up hearing, are telling these stories.

Comics have long been inspired by myths. Look no further than Marvel’s use of Thor, Loki, and the rest of the Norse pantheon. There is Banshee, an Irish mutant whose powers were inspired by Irish folk tales. DC has drawn from Greek myths in creating the world of Wonder Woman. Native American cultures have been tapped as well. Moonshot, Forge, and Echo have indigenous origins. To be fair the tales in The Woman in the Woods are not superhero stories. While superhero stories often use the trappings of myth and legend as a foundation for their own fantastical realities, these are retelling the tales with either a more current setting or a broader lens.

There are two things that set this book apart. The first is that the stories are being retold by people within the culture, not used as a jumping-off point by those from the outside. As a writer myself, I am unwilling to decry well-researched, respectful exploration outside of one’s own cultural heritage. On the other hand, it is important for those within a culture to be able to explore and reclaim it.

Secondly and perhaps more significantly, these versions are also beginning to unravel four centuries of “white-washing” in the form of squeezing out the LGBTQ elements that were often traditionally part of the broader array of North American Indigenous cultures. As an example, many tribes saw the creator as either inhabiting masculine and feminine properties or as being not gendered in any way. This fundamental difference in mindset allows for more egalitarian gender expression and roles. The “genderfication” of God is a primary tool of patriarchy and has been used oppressively for centuries of Western European culture. It was at a height when Europeans first colonized this continent. For the Puritans, women were not only second-class citizens, they were second-class beings, not fit to speak in the house of God. Within a system that had no tolerance for anything beyond the very strict binary gender roles, there was no room for any deviation or LGBQT expression. While many legal and social advances have been made in the intervening years, there is more yet to be done. Books like this, with authentic tales and nuanced depictions of a wide variety of characters, are important to that progress.

I happened to catch this book on the Kickstarter campaign, but I will be going back to the ICC site and ordering others in the series of Cautionary Fables and Fairytales.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply