From the title of his latest graphic novel—The Con Artists—Luke Healy lets the reader know what they’re getting into. The question, though, is who the con artists are and who they’re conning. And, of course, to what end?

Healy then immediately tosses the reader into one of the cons that may or may not be taking place in the work, as the first four pages of panels are Healy’s directly addressing the reader. He says he’s been asked to read a prepared statement, which is nothing more than the traditional disclaimer about the characters being fictional and any similarities to real people or events as coincidental. That’s a fairly standard statement for books and movies, but it’s usually found on the reverse of the title page or at the end of movie credits, somewhere most people wouldn’t notice it. Healy, though, wants to draw attention to that statement, as it will form one aspect of the core of the book.

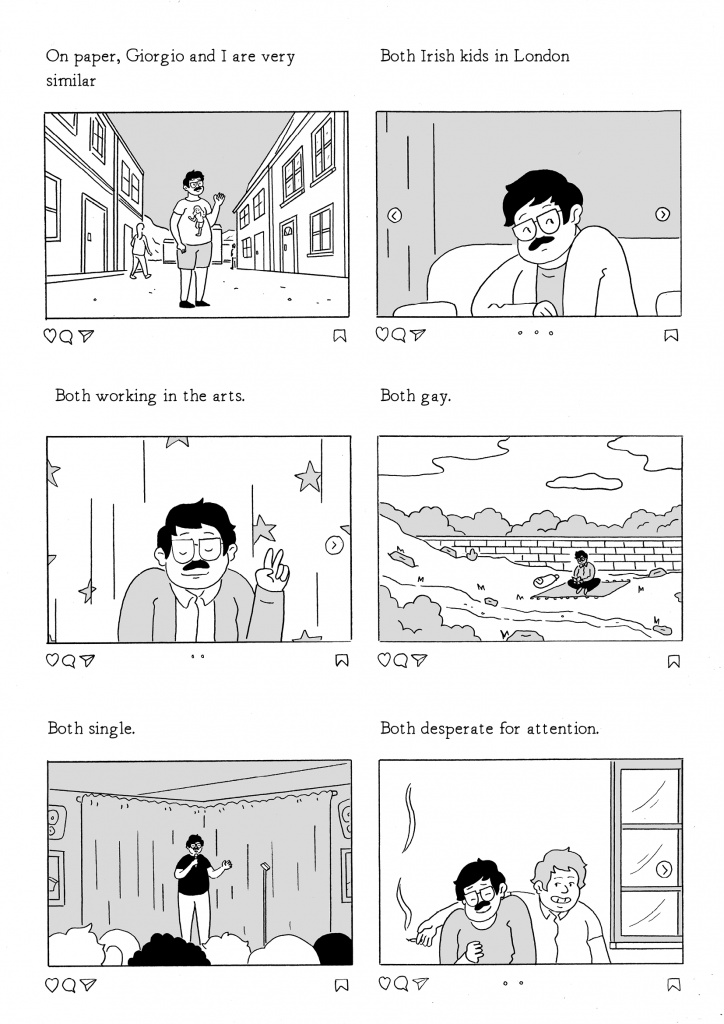

As Healy is reading the statement, he moves toward a dresser where he changes glasses and shirt, while adding a fake mustache, becoming Frank, the main character of the work. It’s clear, then, that Frank is a thinly veiled version of Healy and, thus, that the following story is based on Healy’s life. At one point in the book, as well, after Frank is punched, the glasses and fake mustache have been knocked off, making it clear the disguise is supposed to be a disguise throughout the entire work. This work is fictional, but barely, and there are definitely similarities to real people, if not events. Or at least his art makes one think, while his words say the opposite.

One on level, then, Healy is reminding the reader that art, in and of itself, is a con, though it’s one readers readily accept. Even if Healy were to draw and write a graphic memoir, it would still be a representation of what happened, not the actual events themselves. There is no way to accurately represent the events, so Healy accepts that limitation and admits it to the reader. He even puts in an intermission where he directly addresses the reader, again, explaining that they might need a break after the “tense, and entirely fictional, drama” (112) they’ve just been seeing. In explaining that they should take a break and drink some tea, perhaps even put the book aside for a couple of weeks, he says, “Ground yourself in reality. What is true in this moment?” (113). The reader doesn’t know what’s true in this moment, though, as they don’t know what actually happened in Healy’s life, which parts of this work are fictional and which aren’t. They don’t even know if the representation of Healy truly represents himself. He probably doesn’t want readers to set the book aside for a couple of weeks, but the reader can’t even know that. Healy is conning the readers, though with their willing participation.

That approach is mirrored in the main plot of the story, the relationship between Frank and Giorgio, a friend Frank doesn’t see often but has known for much of his life. Giorgio has been in an accident—hit by a bus—and he calls Frank from the hospital because he knew Frank would come. Frank begins to realize that Giorgio’s life, as he presents it on social media, isn’t true. Despite appearing well-off and well-employed, Giorgio has lost his job, is deep in debt, and is stealing packages to sell on eBay. At times in The Con Artists, Frank wonders if Giorgio is conning himself. Frank believes Giorgio is an alcoholic, which is why he was hit by the bus, then later collapses on the sidewalk causing some head trauma, but Giorgio won’t admit he drinks too much.

Near the end of the work, the reader feels as if Frank has figured out Giorgio’s con, so they feel like they understand him, as well. However, Frank ultimately contacts Giorgio’s parents, which Giorgio has asked him not to do. That call, though, seems to solve all of Giorgio’s problems, making Frank wonder if that’s what Giorgio wanted all along. Frank wonders if Giorgio has not been conning himself, but conning Frank in order to get out of all of his problems. Like Frank, though, readers can’t know Giorgio’s motives, so they can’t know if Giorgio has been sincere or nothing more than a con man.

Frank, though, might also be a con artist, scamming both himself and others. It’s unclear through most of the work why Frank helps Giorgio at all, given how infrequently they see each other and the way Giorgio treats Frank. Giorgio treats Frank almost like a servant, commanding him to perform actions that will help Giorgio and almost never thanking him. One explanation for why Frank helps Giorgio comes from a relationship in Frank’s past, his relationship with Alex. Alex called Frank often, as Alex was suicidal, and Frank often had to talk Alex through such feelings. However, Frank didn’t pick up one night, even texted him to stop calling, which Alex did. Alex was then hospitalized after a suicide attempt. Alex survived, though, and Frank describes Alex as doing better (much better than Frank, which evokes some jealousy), but Frank still feels guilty about ignoring Alex that night.

However, it’s much later in the book that the reader finds out the real reason Frank has been helping Giorgio all along. Frank has been unable to admit a reality about their relationship to himself, conning himself into believing he’s simply being a good friend, and, thus, conning the reader into believing Frank is somebody he’s not. Because readers only see Frank’s point of view, they only realize the extent of the con when Frank admits a truth he’s been hiding.

Frank might be a con artist in a different way, though. While Healy is a cartoonist, Frank is a stand-up comic (which Healy also is), both performers and artists in their own way, and both professions where the artist might draw from their personal lives. When Frank accuses Giorgio of being an alcoholic, Giorgio accuses Frank of having ulterior motives in helping him: “Oh sure, you’re ‘helping me out’—but not for my sake. For yours. Because it will be a good story, right? Frank the hero’s crazy friend gets hit by a bus. Frank’s crazy friend is a thief, so Frank packs up and leaves in fucking secret” (106). Frank doesn’t deny this attack, and he does segue into a stand-up routine at various points in the work. At the end, in fact, it’s clear he is going to use the experience as material in his routine, just as Healy is using it as material for his graphic novel.

Healy’s art works as a contrast to the main themes of the work, as it is clean, clear, and fairly realistic. The page layouts are almost always a typical, six-panel spread, though he switches to four panels when directly addressing the reader. Healy uses black and white throughout for a crisp presentation, though the truth or reality of the work is far from black and white. Instead, each character’s motivations, even Healy’s presentation of the story, are nothing but shades of gray.

The reader, then, is left wondering what actually happened and why. Those doubts not only move out to the idea of art itself (there’s a reason Healy’s book is titled The Con Artists and not The Con Men), but to the reader’s life itself. They have to ask not if they are conning others and themselves, but how and where, in addition to where they’re willingly allowing others to con them. Healy leaves the reader with valuable questions, but not any clear answers, which is not only his point, but the point of art itself.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply