If the first three issues of NOW had bigger names in the world of alternative comics and somewhat conventional storytelling as a way of reaching a slightly broader audience, editor Eric Reynolds set that idea on fire for the fourth issue. This is the first issue of NOW that feels like an underground comics anthology, and by that, I don’t mean a tedious chase of wannabe taboo-busting and id self-gratification. Rather, there is some genuinely weird and challenging storytelling in this issue, and, while Reynolds sometimes has trouble making it all flow together, it’s at least an interesting attempt to move in a different direction.

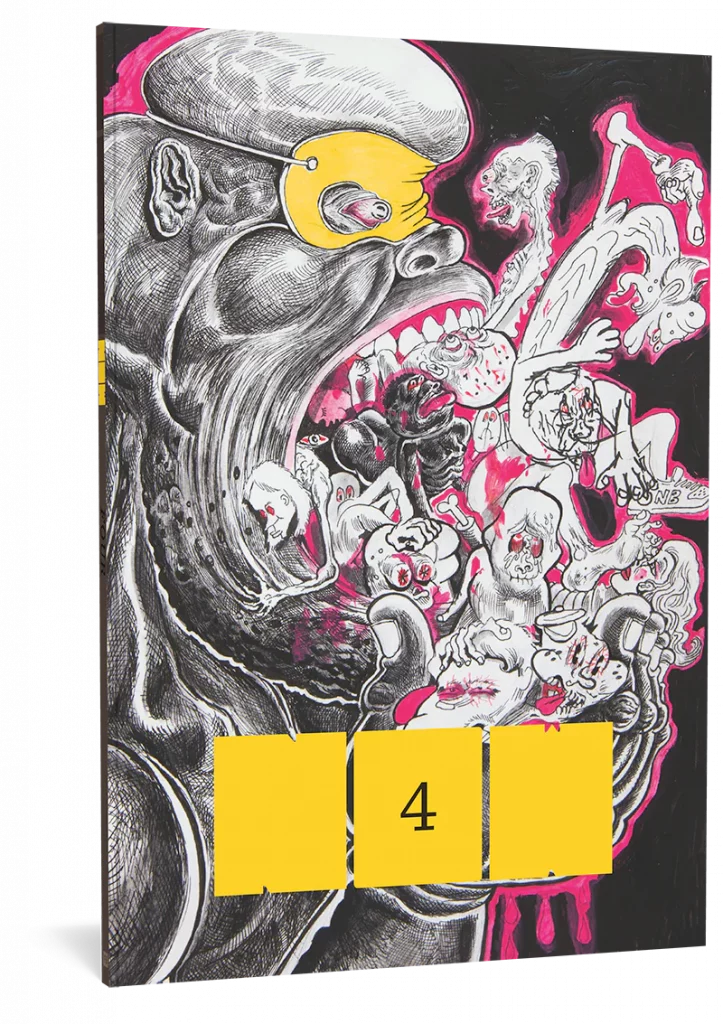

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s cover is very much in that underground spirit, as it’s a heavily cross-hatched drawing featuring a giant, muscular, masked figure devouring weaker, more sensitive souls. It’s as though he was a superhero, devouring other forms of comics and culture. John Ohannesian’s painted and stiffly posed strip makes a joke about art never being valued in the present and only appreciated much later. These are fairly self-deprecatory images for an anthology that otherwise takes so many risks, but while Reynolds believes in comics art and takes it seriously, he’s not so serious that he can’t poke fun at the attitudes surrounding aspects of the art form and the value of art in general.

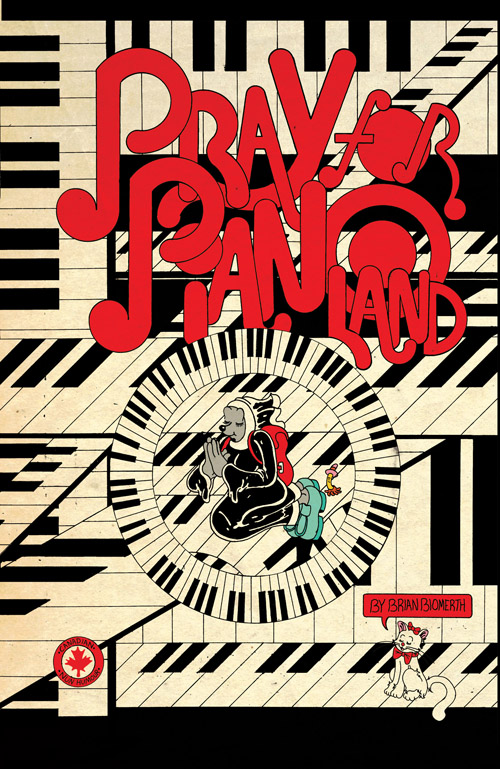

Brian Blomerth’s bizarre “Pray For Pianoland” feels like Kim Deitch, Floyd Gottfredson, Marc Bell, and half a dozen other cartoonists and cultural signifiers put into a blender and poured out on the page with an astounding level of skill and a sense of page composition that’s just dizzying. The absurd plot involves a nun who sells her bathwater, a psychedelic hot dog salesman, and the trippy lair of rebellious shrimp. There is an intentional stiffness to the way the characters move that’s a constant throughout the issue. Cynthia Alfonso’s “From Noise To White” goes in a different direction, as it’s a combination of a highly stylized character design and simplified geometric shapes interacting with each other. The narration involves the woman introduced early on bathing in different forms of light from a landscape of prisms, each of which affects her emotions differently.

Julian Glander’s “Skybaby” is digitally composed to create a 3-D effect, with candy-colored pink as the primary color for everything. There’s a narrator creating a distance effect, as the black blob who’s the main character appears to be a re-creation of some kind, as though a computer was trying to simulate something that happened long ago to create a meditation of what it was like to be 12 years old, thinking about clouds, and having a funny moment with his mom. The visual approach is deliberately unsettling, creating an uncanny valley effect that’s countered by the simplest possible version of a person with the black blob. It’s as though the “program” that created the scenario knew how to depict everything but what a person looks like. Like Alfonso’s piece, a feeling of longing is explored and mediated by the extreme stylization of the images.

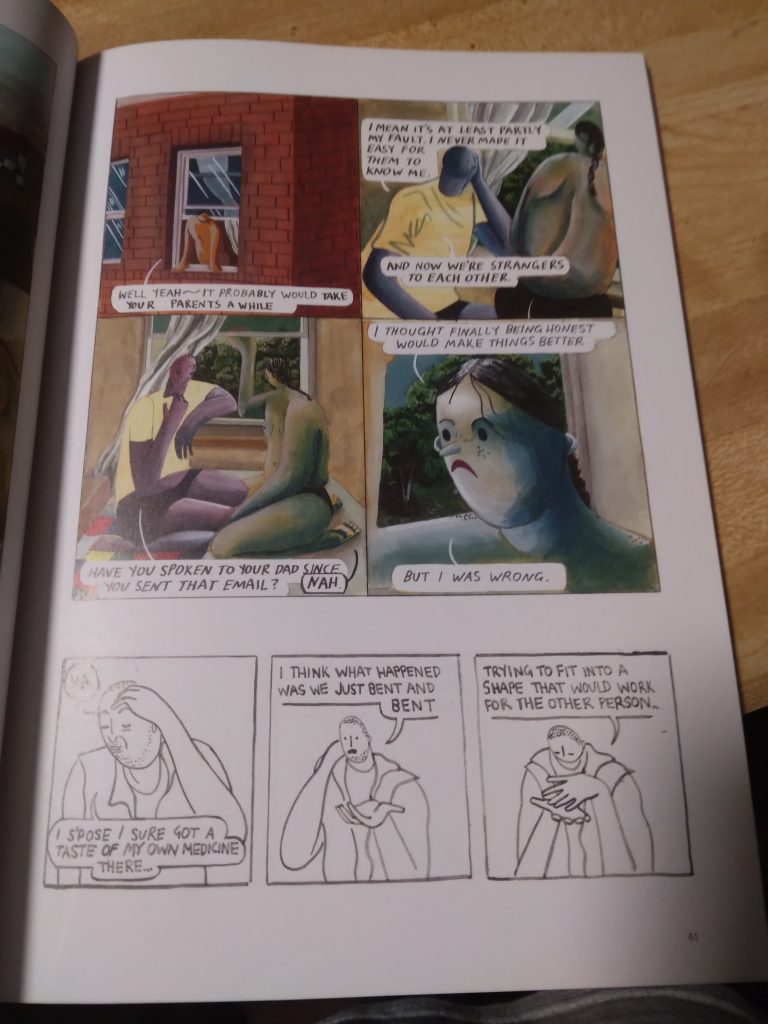

This particular suite of comics ends with a story from Tommi Parrish. It’s Parrish at their best: intimate, visceral, and vulnerable. Their characters are blocky, distorted, and even somewhat grotesque, yet they hold so much emotion thanks to Parrish’s use of gesture. The story follows a couple waking up on a brutally hot day, comparing dreams, and heading off arguments with each other. This is done in full color, but the color isn’t naturalistic; instead, there’s a kind of intuitive emotional flow to the color, as though Parrish was ascribing auras to the characters and their environs. There’s also a parallel narrative in black & white featuring one of the characters doing a monologue about their relationship, exposing a grim past to the idyllic scene that Parrish winds up portraying. It’s exceptionally nuanced and wistful, and an interesting capper to a series of visual experiments that were more stylized but less emotionally resonant.

At this point, the issue pivots to a more traditional cartooning style from the Argentinian team of Diego Agrimbau and Lucas Varela. It’s a funny bit of meta-fiction that riffs on the concept of a character meeting his creator. Indeed, the cartoonist begs off on answering questions, instead praying to god and winding up at a convention of creators. Varela’s art is reminiscent of the sort of thing that Sergio Ponchionne does: cartoony, but with a bit of classic comics elegance.

Nathan Cowdry and Rebecca Kirby follow with pieces that almost bleed into each other; they are fragments of emotions and sensations that relate how the realities of their characters are being warped and shattered around them. In Kirby’s piece, the main character zones out and thinks of others as though she loves them, which means transforming them in her mind’s eye in grotesque and bizarre ways–and then she gets stuck with this vision. That segues nicely into Maria Medem’s piece about someone who sees faces in everything, until her own face is warped beyond recognition.

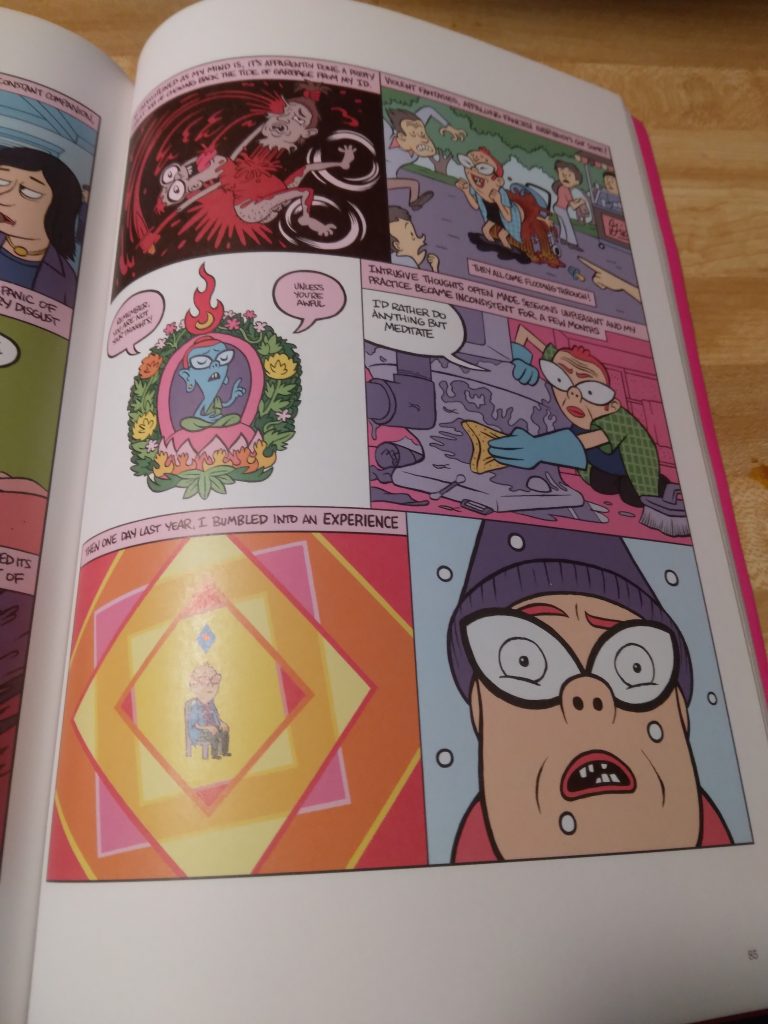

That sense of feelings being warped is flipped by Walt Holcombe, a welcome presence in NOW. In Holcombe’s trademark, classically cartoony style, he discusses his intense difficulties with mental illness. It’s all about his experiences with meditation, and how a particular encounter with enlightenment changed him forever. While it’s an unabashed endorsement of meditative practices, Holcombe’s cartooning and wit are so irreverent that it doesn’t matter.

In comparison, Roman Muradov’s piece feels like much of his work: too clever by half but lacking sincerity. His story about a woman following luck and accidents in order to get her own place in Paris is funny, well-drawn, and smartly designed. There’s no doubt that he’s a skilled storyteller, but for so much of his work, the artifice is all that’s there; it’s not as smart as it seems.

On the other hand, the enigmatic qualities of Matthias Lehmann’s “The Cave” lend themselves to any number of interpretations. It’s about an older woman spending a day in her garden and then with her grandson. There is a strange scene where she is behind him and he starts crying, and then he goes home with his mother. Later that night, when she wakes up, she goes down to the basement, strips off her nightgown, and submerges herself in a deep pool of water, only to emerge on the other side. When she wakes up, soaking wet, she is despondent; she even looks guilty. This feels like a metaphor for something deep and hidden, like abuse, but Lehmann is less interested in specifics and more interested in providing a metaphor for how we bury our memories–until we don’t.

The link to David Alvarado’s story is the relationship between mothers and children. Told in a blunt, simple line with a green tint, the story escalates into a hilariously cringe-worthy series of absurd events, as a petulant high school kid is picked up by his mother who wants to be his buddy. When they go to a disgusting Chinese restaurant, things get really odd, as the place is filled with weird characters and his mother starts dancing to a Led Zeppelin cover band. That final look of shocked horror on the main character’s face in the final panel is especially effective.

The final story in this issue of NOW is another installment of J.C. Menu’s dream comics, which frankly don’t fit in with the rest of the issue, which is why I imagine Reynolds just put it at the end. They’re witty, sharply drawn, and actually make a kind of demented sense, even if they’re a little inside baseball with all of the references to the French comics scene. Menu helpfully provides a little glossary at the end, but it’s really only necessary for the purposes of research, because the actual story works without knowing any of these details. Cowdry offers up another story in “Kewpie,” which is also a comic about comics. This time, a Kewpie doll offers up a critique of a comic drawn by a puppy. It’s hilariously scathing, and the slightest questions on the part of the artist invite a scornful response. It’s a great way to end the main part of the anthology. Theo Ellsworth’s one-pager about a gross practice from a daily dog is a final statement of this issue’s ultimate weirdness.

NOW #4 lacks the clever cohesion of the earlier issues, and a lot of the stories feel thin or deliberately showy. However, Reynolds takes some risks, and while they don’t all work the way he wants or anticipates, they are certainly a departure from safer fare.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply