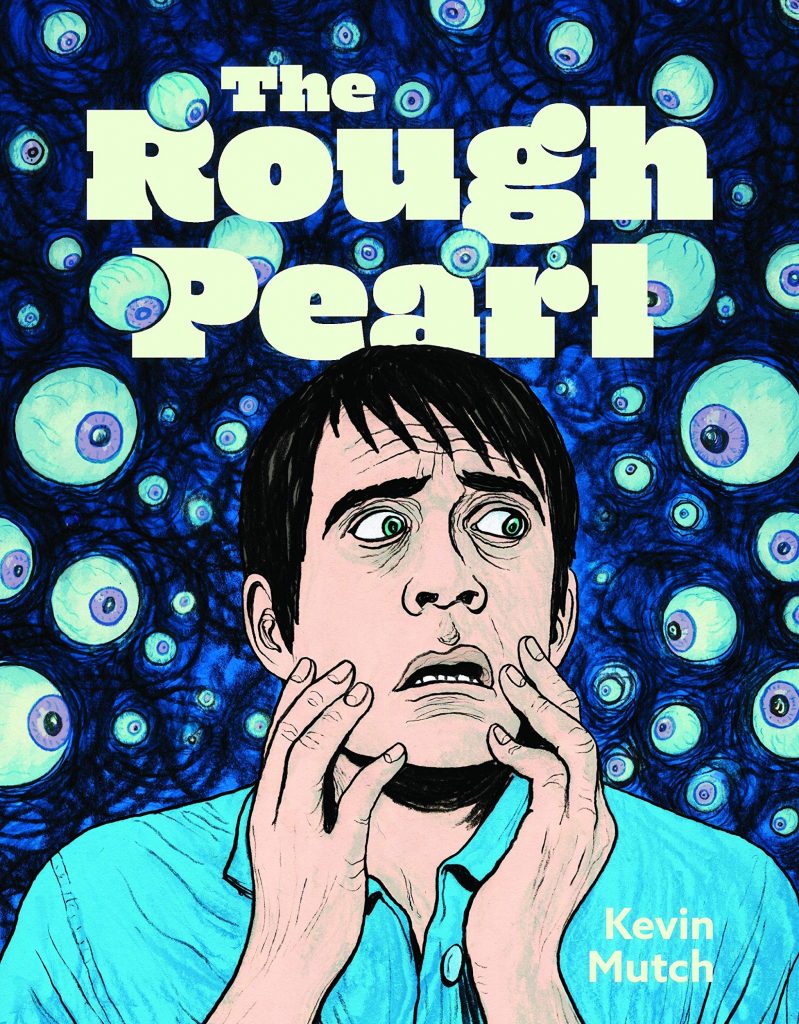

One could be forgiven, given that it features a glow-in-the-dark cover, for thinking that former Xeric Grant-winner Kevin Mutch’s new graphic novel, The Rough Pearl (Fantagraphics, 2020) must either be a “gimmick” release in and of itself, or at least be in need of gimmicks to sell it, but the truth is that it’s a substantive and unsettling work that does more to shine a light on the so-called “plight” of the middle-aged mediocre white guy than any number of New York Times “Let’s Go Talk To People In ‘Trump Country’” puff pieces. Which still probably won’t be enough to convince most people that an examination of the fracturing psyche of a member of the privileged class is necessary in any way, shape, or form — nor, frankly, should it be — but Mutch is offering something more here than the typical “Sympathy For The Devil” narrative, and that makes his book, while admittedly flawed, at the very least interesting and partially revelatory.

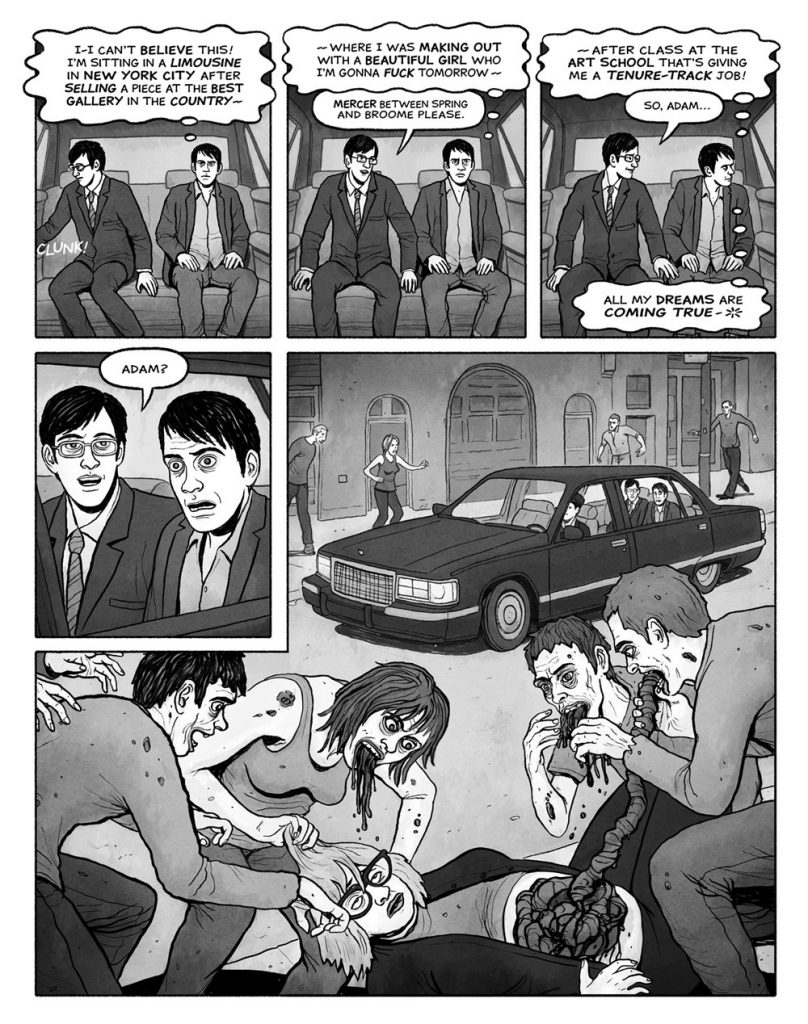

Supported as it is by a “hook” that partially attaches his narrative to currently ”hot” popular culture genres — specifically zombie shit — it’s clear that Mutch is aiming for a mass audience here, but he’s at least availing himself of the opportunity to confront the ever-elusive “casual reader” with some uncomfortable truths. Given that his protagonist, Adam Kline, isn’t a stereotypical un- or under-employed blue-collar worker in “flyover country” but is, in fact, a quasi-cosmopolitan, if career-dead, adjunct art school instructor, it’s clear that Mutch is not examining the purportedly-slipping social and economic status of the straight white cis-gendered male from the usual point of view.

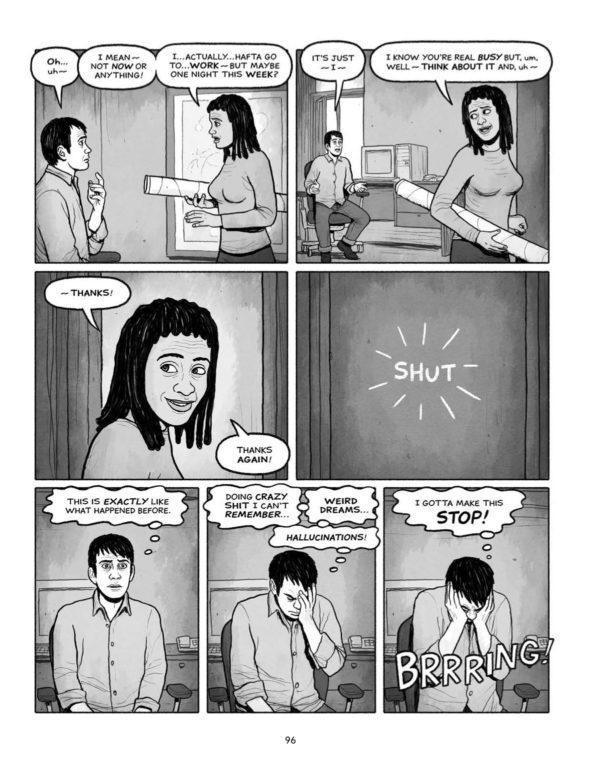

You’re not likely to find Adam wearing the red-and-white “MAGA hat” that has polluted our body politic and cultural landscape, then, but he does share many of the illusory grievances of the Trump crowd: he feels himself trapped in a cul-de-sac of a job, he has a tough time relating to the social and even demographic changes around him, he’s rapidly losing touch with youth culture, and he’s got a severe blind spot when it comes to recognizing his own culpability in terms of where he finds himself in life. He sees all his problems as someone else’s fault, or perhaps just the fault on an uncaring hand of fate, but it’s worth noting that everyone who seems to “trigger” his self-pitying is either female, a person of color, disabled, LGBTQ+, or any combination thereof.

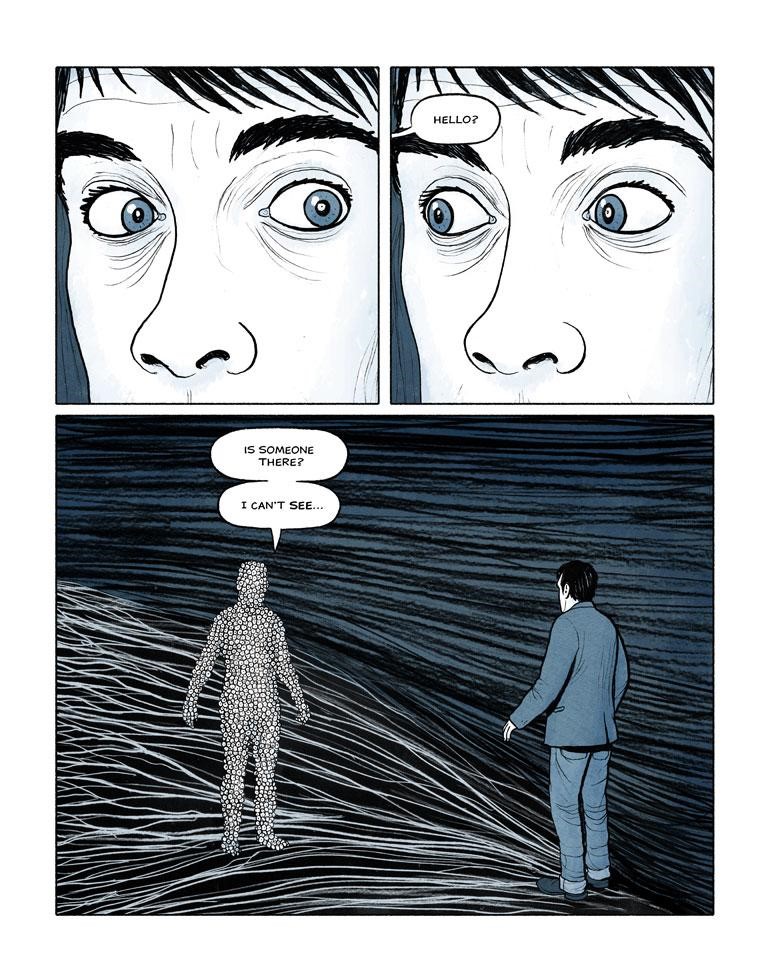

In Adam’s case, things are taken to a greater extreme, however, in that he’s finding himself increasingly prone to nightmares, waking hallucinations, and what’s colloquially referred to as “lost time.” Mutch’s cartooning is technically exemplary — detailed without being over-rendered, with impeccable first-person POV “camera angles” — but it lends itself to charges of being perhaps a bit too “matter of fact,” with little to differentiate the “far out” from the mundane. I think, however, that’s the point: when he’s envisioning zombie-apocalypse scenarios or conversations with eyeball-laden creatures on the astral plane everything has a remarkably “normal” look, even when what’s being depicted is anything but normal. To my understanding, this is where the real horror for those who suffer from hallucinatory incidents is to be found — they seem completely run of the mill, even when the conscious mind is often screaming on the inside that they’re absolutely not.

It would be easy, I suppose, to feel a certain degree of sympathy for Adam, then, but Mutch never takes the easy route here: his protagonist’s loveless marriage is clearly shown to be a result of his own inattentiveness, his yearning for a mythological past where he thinks he was on the verge of being a great artist is portrayed as the pathetic starry-eyed romanticism that it is, and his pursuit of Regan, an intriguing and idealistic student in his class, is at the very least borderline predatory in nature. How much of this is truly happening becomes a more open question as the book progresses and we begin to suspect that’s it’s not zombie hordes and eyeball creatures that Adam is conjuring out of thin air, but it’s worth considering that even if he’s imagining everything, he hardly comes off smelling like a rose and is only a blameless victim of the times and circumstance in his own mind — which clearly isn’t functioning very well to one degree or another. It’s one thing to be a navel-gazing asshole with no ability to see yourself as such — it’s another thing altogether to live in a dream world where you’re still a navel-gazing asshole and still can’t see yourself as such.

The publisher’s back-cover promotional blurb for The Rough Pearl states that Mutch “skewers the pretentious world of academia and the soul-crushing New York art scene” — and so he does — but going after those targets is so easy that doing so is pretty much like shooting fish in a barrel. Mutch’s real target is a combination of ennui, self-absorption, and entitlement. The fact that his sense of entitlement is more intuitively — perhaps even reflexively — absorbed than it is consciously subscribed to makes it all the more insidious and difficult to overcome. The obvious problems that plague Adam are one thing, but the less obvious ones — the ones that he’s not even pre-disposed to recognize, much less to overcome — examining those is Mutch’s actual raison d’etre here. The end result is a work infinitely more challenging and multi-faceted than one would expect from a book with a glow-in-the-dark cover. And for what it’s worth, that glow-in-the-dark cover actually does look pretty cool.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply