Frank Santoro’s extremely personal family memoir, Pittsburgh (New York Review Books), masterfully uses both Santoro’s expressive color palette and unusual page layouts in exposing how complicated family secrets can be. It’s a multigenerational story that includes both sets of grandparents as well as his parents, and, like many family stories, it’s designed to answer a single question: why won’t his divorced parents even acknowledge each other, even though they work in the same building?

It’s a fascinating and immediately relatable story because it forces both Santoro and the reader to think about something that’s very difficult: regarding one’s own parents and grandparents as normal, flawed people with desires and dreams of their own that may have been thwarted. Much of that information is deliberately withheld from children or grandchildren. Santoro slowly unravels the events that led to his parents getting together and the circumstances that led to his father leaving his mother. Some of these circumstances are particular to Santoro growing up in Pittsburgh, one of the most insular and parochial big cities in America.

Memoirs are tricky. A particular series of events, phenomenologically speaking, should not be perceived differently over time. Yet, it’s unquestionably true that events are perceived differently and memories shift, both from the perspective of the memoirist and the reader. Santoro reveals that much of the family information he writes about in this book, which is clearly heavily researched, was kept secret from him until he was in his thirties. Trying to write about his family before then would have resulted in an entirely different book. This isn’t solely because of what he learned, but also because of how his own personal experiences changed him and left him more open to hearing new points of view. For example, Santoro long blamed his father for the divorce and took his mother’s side. It wasn’t until he was ready to listen and not just start a fight that things changed for the better between the two of them.

As a reader, my own personal experiences of my parents divorcing and feeling resentment toward my own father made Santoro’s story a familiar one. If I had read this book at age twenty, when I was still estranged from my own father, as opposed to age thirty, when we had a reconciliation, my experience of it would have been different. Reading it now at age fifty after my own divorce, I can see the perspectives of the parents, the grandparents, and Santoro all at once. It doesn’t make it any less painful, but it’s at least easier to understand that relationships are messy and complicated.

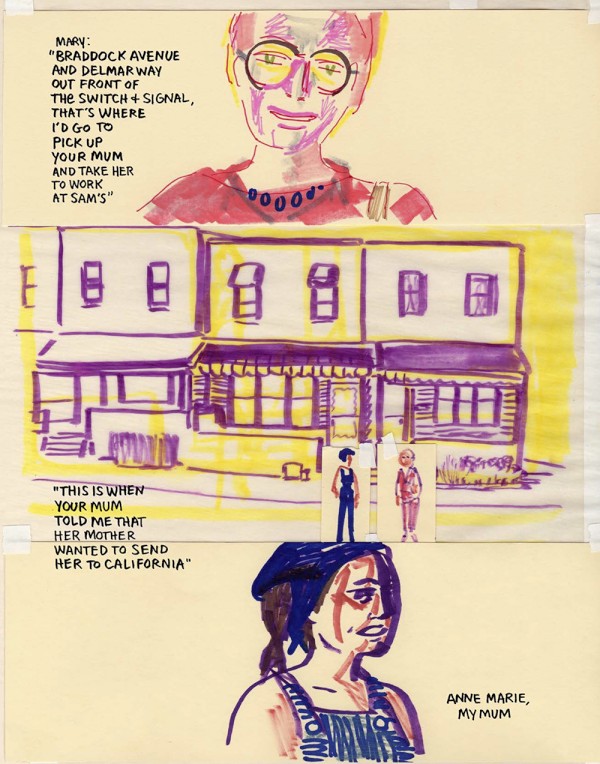

Santoro navigates these turbulent waters with a powerful sense of storytelling clarity. His years of preaching the use of the nine-panel grid as a versatile means of telling a story play out in an interesting way as very few pages in this book make active use of that grid. Instead, Santoro leans on the philosophy behind the grid, one that emphasizes the center image above all else. In Pittsburgh, he collapses the vertical panels on most of the pages so that there are three separate sections stacked on top of each other. The center image is always slightly more prominent and larger in terms of storytelling importance. Many pages have a single panel on the page, bordered at the top and bottom by light shading as a way of framing the image. Using this method allows Santoro to isolate and emphasize particular emotions and memories.

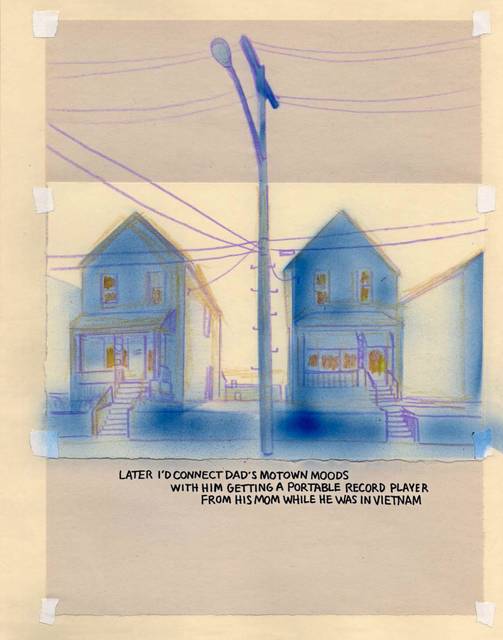

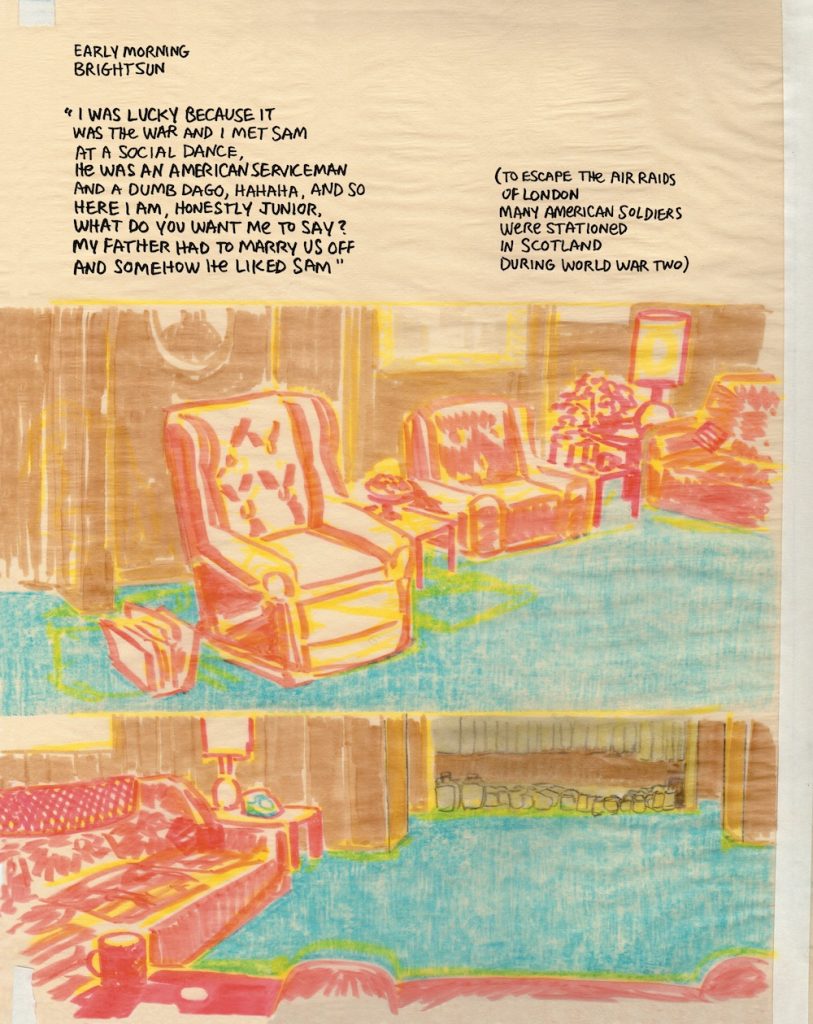

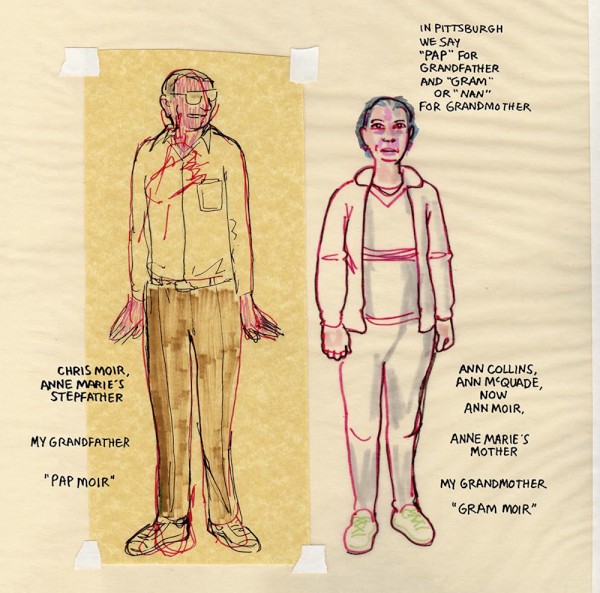

His layouts also mimic photo scrapbooks, and that’s not a coincidence. On many pages, the story is literally constructed out of cut-out figures taped to the page, just as one would paste a photo. As well, his use of color and line is highly expressive and stylized, as though Santoro was recording emotions instead of facts and events. There are a lot of “hot” colors like yellow, orange, and red, but for a philosophical and emotionally open Santoro, these colors represent warm, welcome feelings rather than anger.

That warmth notably extends not just to his extended family, but to the city of Pittsburgh itself. Santoro’s drawings of the bridges and row houses represent a firm sense of what home means to him. That’s signaled first with the warmth with which they are drawn, and then with Santoro’s actual words about the city. The provincial quality of the city plays a role in this story because of the small-town feel of his particular borough. His dad’s family knew his mom’s family, and while his maternal grandmother opposed his parents getting together, his dad’s mom was in favor of it and helped make it happen. Their homes, their businesses, and their leisure time locales were all located in the same five-block radius. This was their whole world, which, at once, felt comforting and familiar for some (like Santoro growing up) and constricting (to others who were in bad situations).

Santoro divides the book into roughly two sections. The first is a relatively straightforward flashback narrative regarding what happened with his relatives. It’s told mostly by his dad’s mom Mary, a hilarious Scot who had no particular love for Pittsburgh yet became a part of it when she moved there after World War II. The second half reveals that every story, every memory, has its own context that’s part of a larger truth. For example, Santoro is told that his mom’s family refused to come to the marriage party after his parents were married in secret. At first, it seems like they’re petty and spiteful. Later, Santoro’s dad reveals that it’s because he cheated on his mom before the wedding; they refused to endorse or approve of him for that reason.

Santoro’s dad leaves his mom because he was tired of being “the referee” between his wife and her hard-drinking, violent family. Santoro’s dad tells his son that he knows he wasn’t a great father, but he wasn’t really ready to be one after surviving a hellish experience in Vietnam. He sticks around only because of Santoro, and when “Junior” (which is what everyone calls him because Santoro’s dad is Frank Santoro Sr.) goes off to college in California and his own parents go to Las Vegas, he leaves his wife. Though Santoro stayed in California at his mom’s behest, all he wanted to do was go back home. For a native of Pittsburgh, the draw of his borough and his city and his family was all one, unifying force.

Santoro’s mom tells him that she still loves her ex-husband, but he broke her heart. As a result, she is sticking to her guns to never talk to him again. So when they see each other at work, both proud, stubborn people will continue to pretend the other doesn’t exist. Santoro, at the beginning of the book, refers to this as “a lie that is killing me.” By the end of the book, he doesn’t like that this is still happening, but there’s a sense of acceptance. There’s nothing he can do about it. Notably, those last two pages where he drops his mom off at work and she ignores his dad are the only two pages that are in black and white. All the warmth and love of the rest of the book is drained away on those two pages. However, Santoro ends Pittsburgh with beautiful drawings of the city’s steel mills and a train coming through a tunnel, light appearing ahead. It’s a direct but beautiful visual metaphor in a story about the people who shaped Santoro and the people who shaped them: all human, vulnerable, loving, and flawed in their own ways.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply