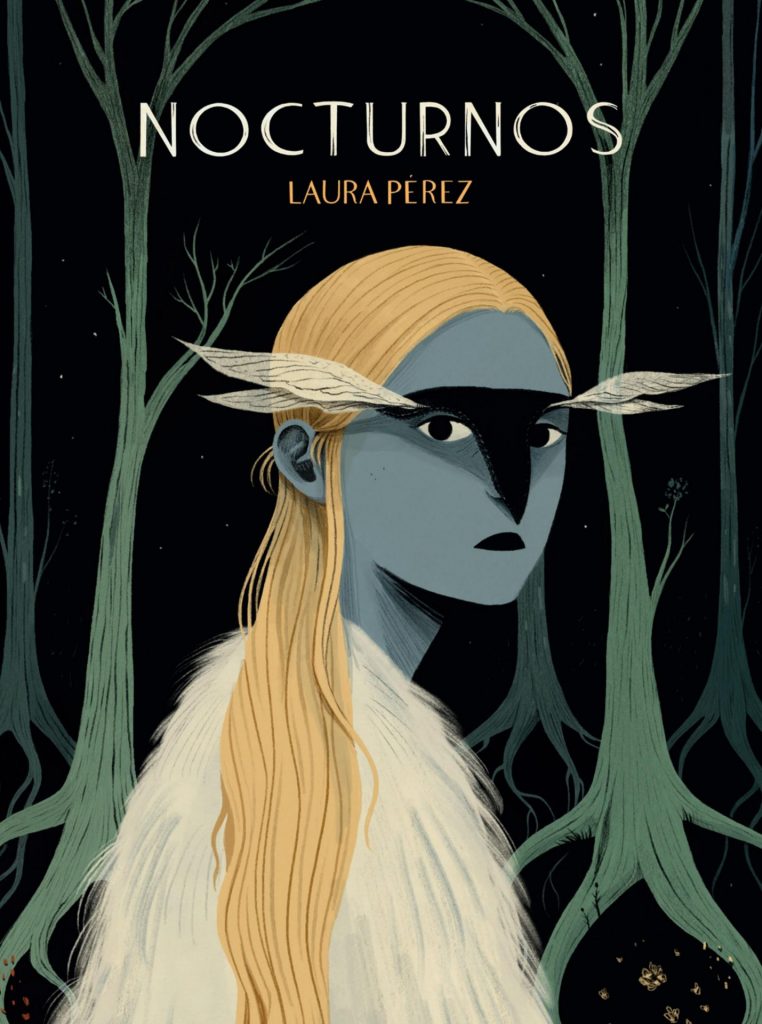

Laura Pérez is a Spanish illustrator and comics artist. Her work has been published by The Washington Post, National Geographic, and Vogue, among many others. In 2022, she was nominated for an Emmy Award for her contribution (with Elastic) to the title design for the television series Only Murders in the Building. Three of her books — Totem, Ocultos, and Nocturnos—have been translated into English by Andrea Rosenberg and published by Fantagaphics.

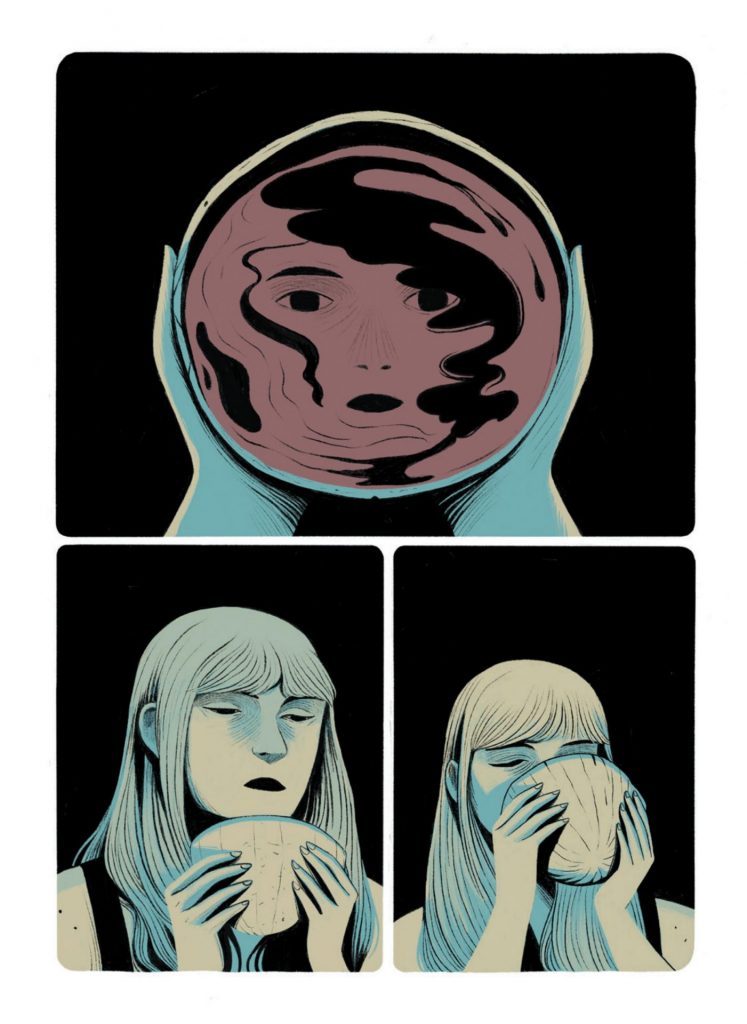

Her comics are impressionistic narratives created with delicate line work, desaturated color palettes, and dreamlike scene transitions. Argentine neogothic horror writer Mariana Enríquez described Nocturnos as “a beautiful and melancholic love song to the mysteries of sleep and the night.” Writer and critic Aria Baci was fortunate enough to talk with Pérez about her inspirations, explorations, and the relationship between the feminine and the gothic.

Aria Baci: What inspired you to transition from illustration to comics? Have you always enjoyed comics, or did your work in illustration lead you down a path toward comics-making?

Laura Pérez: I’ve always been interested in telling stories, and after 11 years working in the world of illustration, I started to feel like I wanted the characters to not disappear so quickly, to have some stories behind them. I had never been a big comic book reader, but I’ve become more interested in them over time, and now I’m curious about many different kinds.

Baci: Something I love about your style is the simplicity of your visual design and the elegant use of light and shadow. It looks almost animated, but it’s also very poised. Do you conjure inspiration from any particular sources?

Pérez: The first influences I remember were Norman Rockwell, with his orange tones, subtle shadows, anatomical forms, and expressive gestures. Then I discovered — and was amazed by — Edward Hopper, with his synthesis of colors, his use of primary colors and simple forms to depict complex elements. More influences followed, from the colors used in Japanese and American animated films, black and white cinema, and directors like Wes Anderson, Sofia Coppola, and Stanley Kubrick, among others.

All of this has allowed me to appreciate with my own eyes the lights and shadows, the colors, and all the possible combinations I see around me.

Baci: When I first discovered your comics Totem and Ocultos, I was immediately mesmerized by the surreality of your stories. Considering other Hispanic artists — from the twentieth-century painter Remedios Varo to the contemporary author Elvira Navarro — is there something about life in Spain that is inherently surreal?

Pérez: The Mexican artists Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, as well as the Spanish painters Salvador Dalí and Maruja Mallo, share in common an array of peculiar elements (unique to each artist) that speak of the subconscious as a way to liberate emotions—which are rooted in the culture and psyche of their personalities — from thought and logic. In a way, they connect with the atavistic yet contemporary symbolism of the deepest human emotions. In Spain, there is a connection to the socio-cultural situation of the epoch, a need for liberation of ideas and freedom of expression through art.

Baci: In the same vein, your comics have a gentle kind of gothic sensibility. I wonder about this as a woman who herself has always been attracted to the gothic: Is there something about the gothic that is inherently feminine?

Pérez: There is a direct relationship between femininity and a sensitivity akin to gothic mystery, female empowerment, breaking free from the confines of the home, or finding mystery and subtlety within them — the repressed, the unspoken, the hidden, and everything that is not revealed at first glance. It’s a way of seeing the world and its deepest subtleties, as well as a connection with the night and the natural world, and also the architectural or natural context to frame stories that often move between everyday life and mystery.

Baci: You begin Totem with a quotation by Carl Sagan: “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,” immediately establishing that your comics are going to explore uncanny or inexplicable experiences. Can we talk about how this willingness to explore the unknown informs your work?

Pérez: I’m interested in what has naturally interested humanity throughout history: trying to understand the nature of our reality, knowing that our capacity is limited and that our progress in knowledge is slow and cumulative, building up over generations — although we also need to return to ancient knowledge to gain a broader perspective of our history and exploration of the world.

Everything we don’t know is a mystery. From there, we can explore a vast range of unanswered questions. In my comics, I try to raise some of these questions without attempting to answer them, leaving the reflection open for the reader. You don’t need to understand everything to be able to experience it.

Baci: I ask about the unknown because your comics have an almost childlike sense of wonder about the natural world, spiritual energy, and even death, without any concrete explanations for some of what happens from panel to panel. Do you think mysteries don’t always need to be solved?

Pérez: We all experience life for the first time in some way, and the mysteries of existence are passed down from generation to generation — the same questions, the same fears, the same mistakes, the same epiphanies and moments of clarity — all those mysteries that happen to us for the first time, and for which we have no answer other than our own analysis and accepting that they happen to us. Everything has an answer, but that doesn’t prevent us from learning from the emotions they provide.

Baci: One of my favorite scenes in Totem that is as endearing as it haunting: While visiting a country house on holiday, a young girl removes objects from a shelf in her bedroom and leaves them at the gravesite of a girl her age who was buried near the house. Piece by piece, she replaces the items from the house with objects from the natural world that have been left outside her window. The implicit narrative here is that the items are being left by the ghost of the girl buried nearby. But beyond that, I was super intrigued by the way the living girl offers manufactured items (like a model car or a Rubik’s Cube) while the gifts left for her are objects found in nature (like stones, shells, and twigs). Do you feel that there’s something more magical about organic materials than machine-made artifacts?

Pérez: I’m glad you liked that scene and that it’s comprehensible; it’s a scene I’m particularly fond of. I’m trying to express that for both children, the beautiful thing is sharing what they have with each other, to somehow see that what is happening is real, that they are actually communicating with each other. So [Emily, the girl whose grave it is] brings the girl what she has available nearby: natural objects; and the girl brings [Emily] what she has in her room. The act itself is a magical act of communication between different planes. And I believe that both organic materials and machine-made artifacts have whatever magical quality that we want to give them, whether emotional, related to identity, or memory, all with an animistic touch.

Baci: One of the ideas in Nocturnos is that night is a distinct place, and that it’s a place humans have tried to conquer. That idea reminded me of the wordless sequence that begins and ends Ocultos, in which a woman walks into the starry night like it’s a destination unto itself. Some of the visual details in that moment from Nocturnos are also reminiscent of that scene from Ocultos. Are your stories in any way interconnected?

Pérez: Ultimately, they all form part of the same world, and to some extent, they are a trilogy: Ocultos, Totem, and Nocturnos. In them, I try to explore aspects of the world of mystery, the psyche, and the occult with different forms and characters, with different narratives that connect to one another. Characters appear and disappear, and some characters are subtly repeated throughout the books. Night is a place of metaphor, a liminal space that defines the passage of time. Tomorrow is tomorrow because we move from day to night and back to day, an illusory sense of the passage of time that the night helps us understand. It also represents death and rebirth.

Baci: In your digital comic published by the Museum of Modern Art in August, my favorite panel has the caption: “A work of art is not only what it shows, but everything it hides.” Is this something that you think about as you draw your comics?

Pérez: Drawing a comic book is a long process that takes years, and, during that time, situations inevitably occur in an artist’s life that somehow affect the work. Perhaps they have to revise the tone, perhaps they have suffered a personal loss, good things and bad things, but the work has to continue, and those situations are reflected in the book, even if it’s not obvious. That happens with any work of art; we only see the final result of a process that involves not only technique but, fundamentally, emotion. And the many emotions experienced throughout that process.

Baci: English readers have only recently been blessed with the translation of Nocturnos. Are you already working on your next book? Can you share anything about your aesthetic or narrative vision for it?

Pérez: I’m very happy because just today I saw that The Washington Post has chosen Nocturnos as one of the books of the year, and the New York Public Library did too, so I’m thrilled with the reception of the third book I’ve published with Fantagraphics.

I’m currently working on a book in collaboration with Guillermo Corral, and also writing the script for another solo book. So I’m working on two books: one that will come out next year and one that will come out in several years.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply