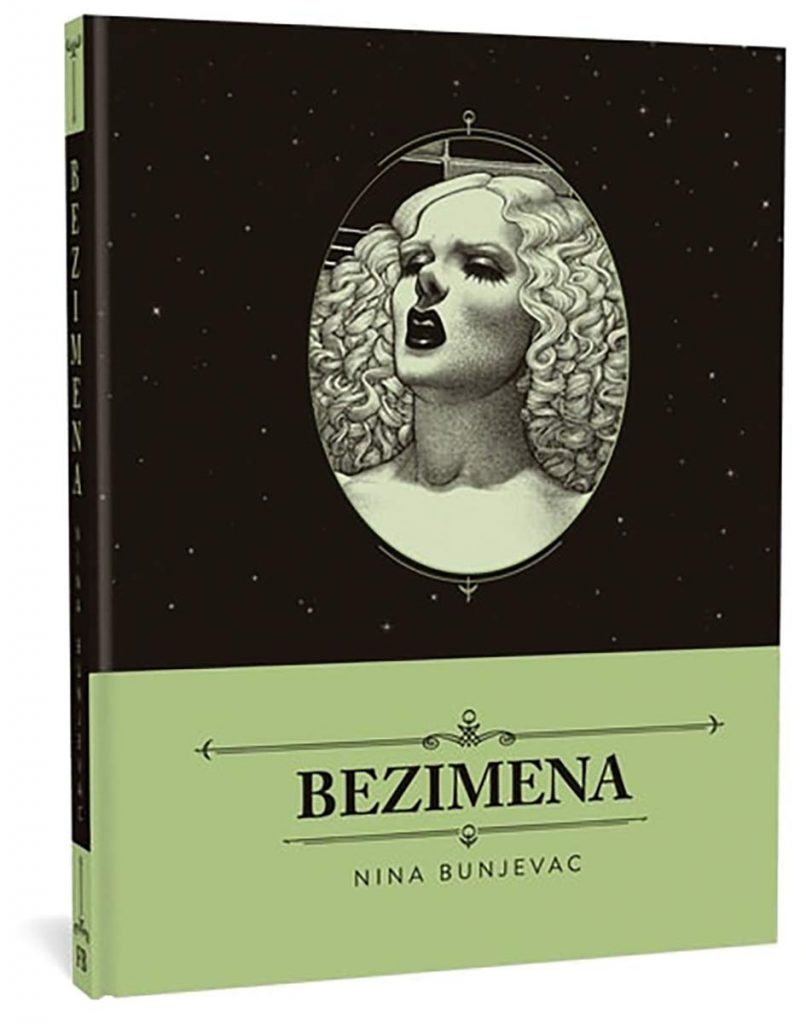

Trigger warning: sexual assault, trauma. Confronting the effects of sexual trauma is like negotiating a pitch-black labyrinth. There’s no game plan for escaping it; there indeed may be no escape. What has been done to the victim, how the victim internalizes it, and finally how the victim externalizes it are intractable problems. Nina Bunjevac’s approach in Bezimena (Fantagraphics) is to attack the issue from as many points of view as possible. There are scenes of explicit sex and violence rendered in Bunjevac’s trademark, highly detailed stippling style that embody both horror and eroticism. There’s no escaping the darkness present on each page, but there’s also no escaping the raw desire, that sense of how a damaged person can choose to cross a line and do irreparable damage to the innocent. For as many storytelling layers as Bunjevac puts between the reader and the most horrific elements of the story, the images themselves tell the ugly truth.

This is a story telling a story. There are two unseen, unnamed storytellers, one of whom tells the tale of Bezimena to their curious friend. On the first page, it is revealed that the first storyteller spins the story in response to a story they were just told by the second storyteller. What was this other tale? It’s not revealed, other than that the first storyteller was reminded of it by “the words you speak so well.” What could possibly bring to mind such a horrible scenario, a story where trust is broken and the innocent are harmed? The answer is a similar kind of story, and I would argue that in an elliptical fashion, the first story is Bunjevac’s own story. In the afterword, Bunjevac reveals her own nightmarish account of a friend leading her into a trap with a sexual predator that she barely escaped from when she was 15. She also alludes to a later sexual assault by someone she looked to as a protector and admired. Bunjevac notes lingering guilt because not long after the first encounter, she was sent to live in Canada, and so she never helped bring that abuser to justice.

In the book, the character of Bezimena is vague. She is referred to as “the old,” and she’s a figure of authority that a priestess turns to for help. Is she a goddess? A dark spirit of some kind? A crone? In Bunjevac’s native Croatian, bezimena literally means “no one.” There are allusions to mythology throughout the book, and the back cover refers to the myth of Artemis and Siproites, where the goddess of the hunt turns a boy who saw her bathing into a girl as a punishment. The dehumanizing power of the male gaze and its destructive potential is a running visual theme, as the humanity of the victims in the story is replaced by the iconic power of the fantasy image.

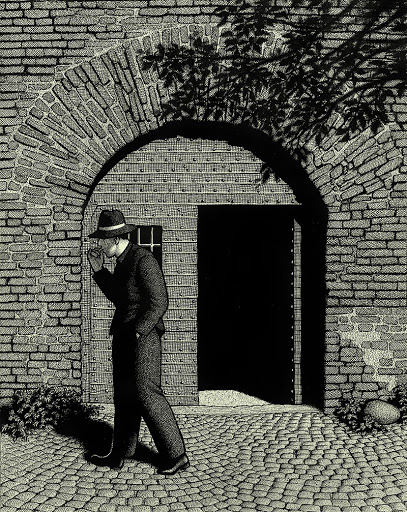

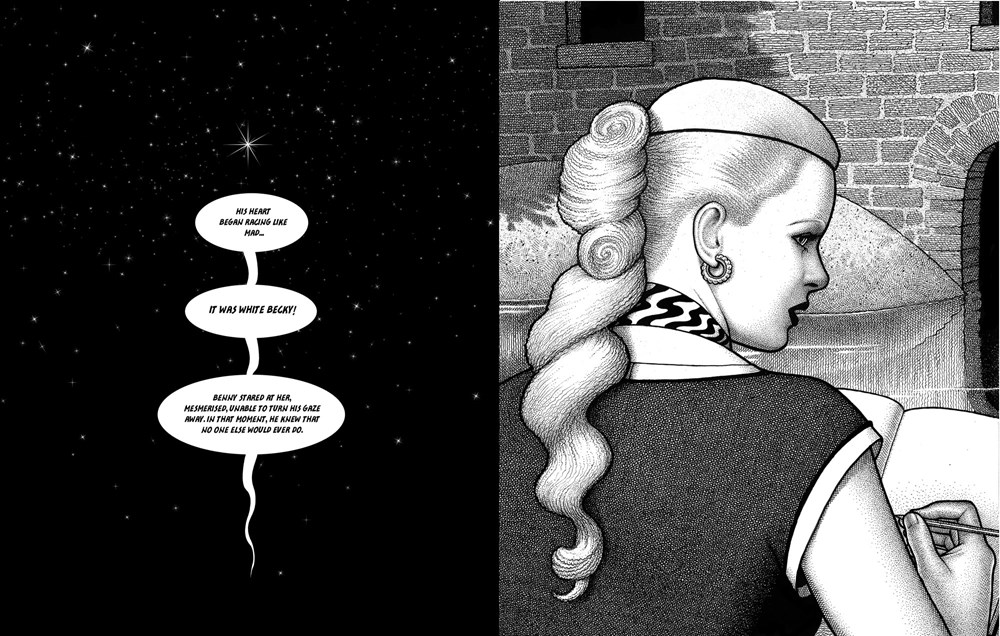

In the story, Bezimena is annoyed by the priestess coming to her yet again because her temple was being desecrated and destroyed. Bezimena’s reaction is to grab the priestess, dunk her underwater, and trigger a process where the priestess is reborn as a boy named Benny. He has a normal childhood and loving parents. At a certain point, he can’t control his obsession with girls and public masturbation. He learns not to do this in public, and, as he grows up, he contains his voyeurism to the edges of his job as a janitor at a zoo. One day, he sees the object of his childhood obsession (“White Becky”) all grown up and follows her. He discovers a sketchbook she left behind that contains all sorts of highly sexually explicit drawings that also portend the future.

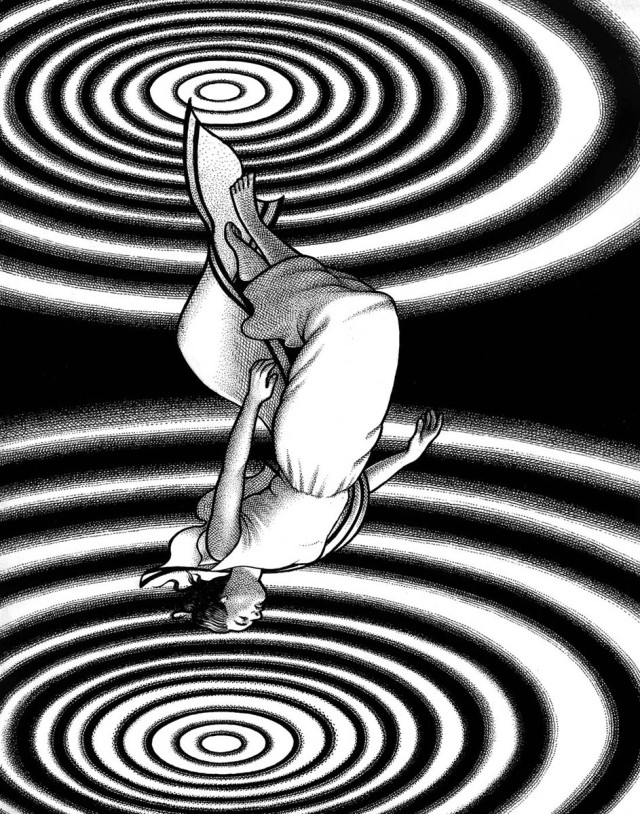

In a series of scenarios, he enacts the events from the sketchbook, which are highly posed and frequently violent sex scenes. Over time, each scenario and the dreams he starts to experience become more surreal, symbolic, and disturbing. When he finally reaches his goal of “White Becky” herself, he feels more alive than ever, even as he loses all connection to reality. That’s when the cops come calling and reveal that he’s under arrest for raping and murdering three little girls. The sketchbook is nothing but a book of children’s drawings, and Benny hangs himself in jail, insistent that he did nothing wrong, that it was all a misunderstanding. At that moment, he returns to being the priestess as Bezimena yanks her head out of the water, asking, “Who were you crying for?”

The afterword makes it clear that this book is Bunjevac’s attempt at shining light in the dark places of her own life and memory. However, she also dedicates the book to “all forgotten and nameless victims of sexual violence” and hopes that they may “dispel the darkness that envelops you.” She’s very careful, as the first storyteller unravels the story, to keep the narrative tone as neutral as possible, forcing the reader to see the story from the point of view of the killer. By focusing on the most lurid fantasies of an abuser and forcing the reader to truly inhabit them, Bunjevac’s aim is to simultaneously horrify the reader and get them to understand that abusers choose innocent victims because of their own self-hatred and pathetic, stunted imaginations.

What makes Bezimena a challenging work of art is that Bunjevac avoids telling what could have been an explicit, powerful, and direct autobiographical story about her experiences. However, she wanted to go deeper than that. She wanted to go as deep into the darkness of a warped id as possible. By going all the way through Benny’s madness, she takes away its power. She cuts through the darkness by creating darkness on the page before eventually revealing it as a trick, an illusion. Abusers and predators often spin elaborate fantasies as a way of justifying their crimes, as well as othering and dehumanizing their victims. Bunjevac shatters this self-valorization while detailing exactly how it works. The sex scenes are staged like photos from a magazine instead of having the fluidity of a sexual encounter. The sex scene with “White Becky” literally has Benny sticking his finger through one of the omnipresent, metaphorical keyholes in order to violate her. It’s the ultimate dehumanization, where she’s simply reduced to a detached body part. The mind of a predator does everything possible to destroy any potential semblance of intimacy.

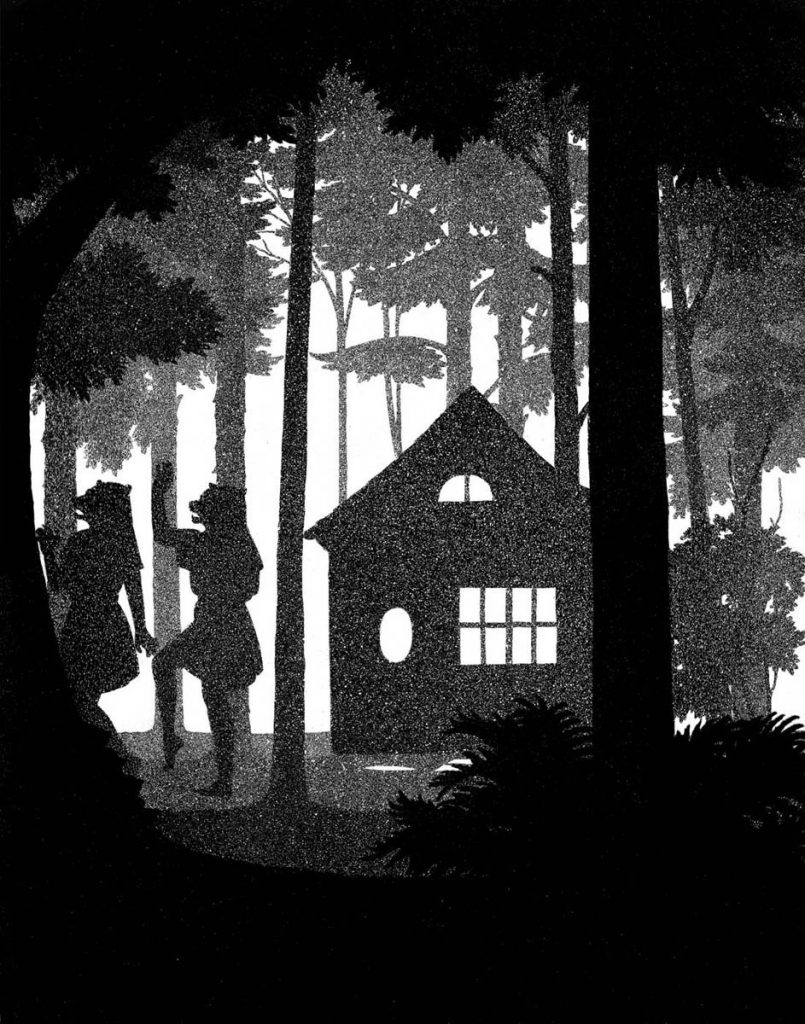

The question remains as to why Bezimena chooses to punish the priestess in this fashion. There is a strong undercurrent of betrayal by an authority in this book. Bezimena betrays the priestess. In Benny’s fevered dreams, there is the silent image of an older, female figure leading a wolf girl through the forest and selling her to a waiting man. His intent is clear. There’s a level at which the first storyteller’s tale is one of simple betrayal. There’s another level at work, however. Bezimena is a supernatural force of some kind and the priestess is an authority on her own. The fact that Bezimena means “no one” is an implication that god does not exist; it’s an empty authority. Why is the priestess being published? Because she’s crying for herself, and not those she’s supposed to protect. She is given a lesson in what authority is and how it can be warped. She is shown the narcissism of her beliefs in the harshest manner possible.

So if the second storyteller is Bunjevac herself, telling a story about an innocent person whose trust has been betrayed in addition to being exposed to multiple predators, then the first storyteller’s response is a story where authority is punished and predators are exposed. It’s a story designed to help Bunjevac with her guilt of not being around to reveal her predator. This is a book about confronting, naming, exposing, and freeing oneself from the kind of darkness that can destroy lives. It’s a gift that Bunjevac gave to herself as well as her readers.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply