It’s initially a little jarring, tonally, that Masumura Jūshichi opens Children of Mu-Town with a frank acknowledgment of the book’s debt to Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets. Yes, Masumura’s book lifts the central character dynamics and large swaths of the basic plot from Scorsese’s film, but where the film seethes with the violence and aimless aggression of its angry young gangsters, most of Children of Mu-Town is quiet and melancholy, a story about slowly fading away rather than passionately burning out. Upon closer inspection, though, that tonal clash is at the heart of Masumura’s book. It’s embodied in the intense emotions buried just beneath its surface and in the stylistic fractures that pepper the otherwise austere art.

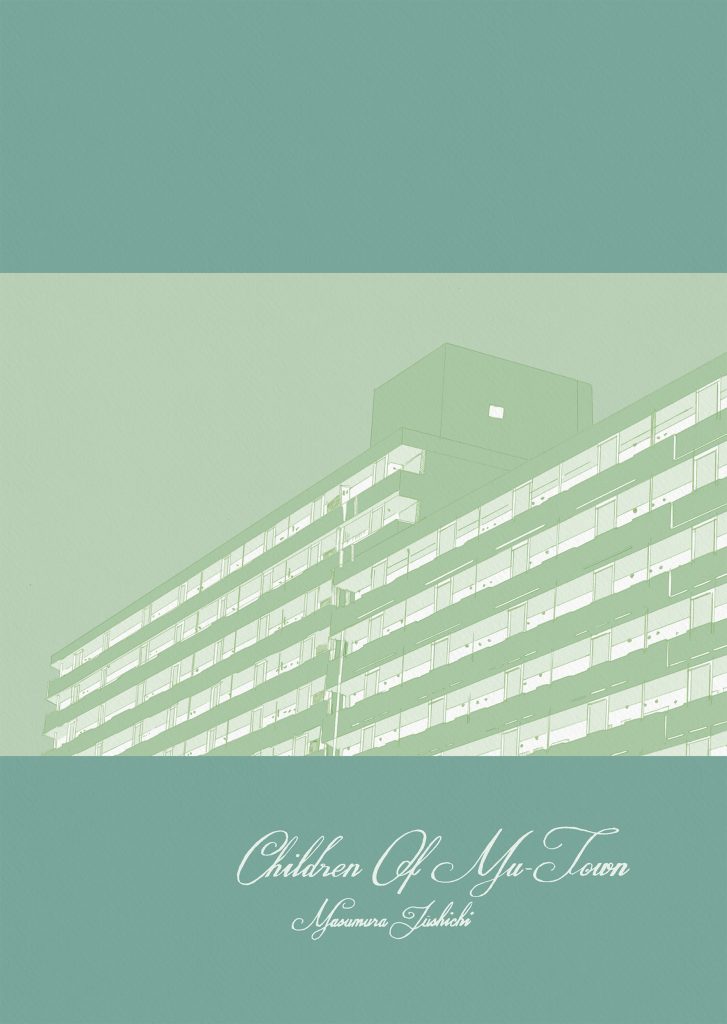

Masumura is a part of Japan’s varied, active, but not-often-translated underground scene, and, as with many of those authors, they choose to obscure their identity, identifying as a collective that currently happens to have only one member. Children of Mu-Town was originally self-published by the author in a four-part minicomic format, similar to the way comics in the United States are sometimes made; the final collection of that comic is now translated into English and published by Glacier Bay Books. It’s set entirely in a declining Tokyo housing project called Marigaoka Park Town, a postwar neighborhood that’s gradually been depopulated. Only the elderly have been left behind, abandoned and isolated, most of the young people having long since fled for places with more opportunity or cachet. Masumura delves into the twisty political and socioeconomic implications of this setting — anti-immigrant sentiment, right-wing politicians, and the lack of opportunities many experience amidst Japan’s larger prosperity – in a way that feels totally organic.

These themes emerge naturally from the story of two friends, Juichi and Hajime, both part of the small younger generation that hasn’t yet managed to escape from Marigaoka’s dead-end tranquility. Juichi is a hanger-on for the yakuza, running petty and mostly innocent schemes around town on behalf of his gangster uncle. He justifies his illicit activities as a way to entertain the town’s lonely old inhabitants, who really would have nothing if not for the minor excitements of gambling nights and the clubhouse atmosphere of the café Juichi runs as a yakuza front. While Juichi at least tries to appear responsible and mature, Hajime is feckless, owes money to everyone, and refuses to bow to the local power structures the way Juichi begs him to.

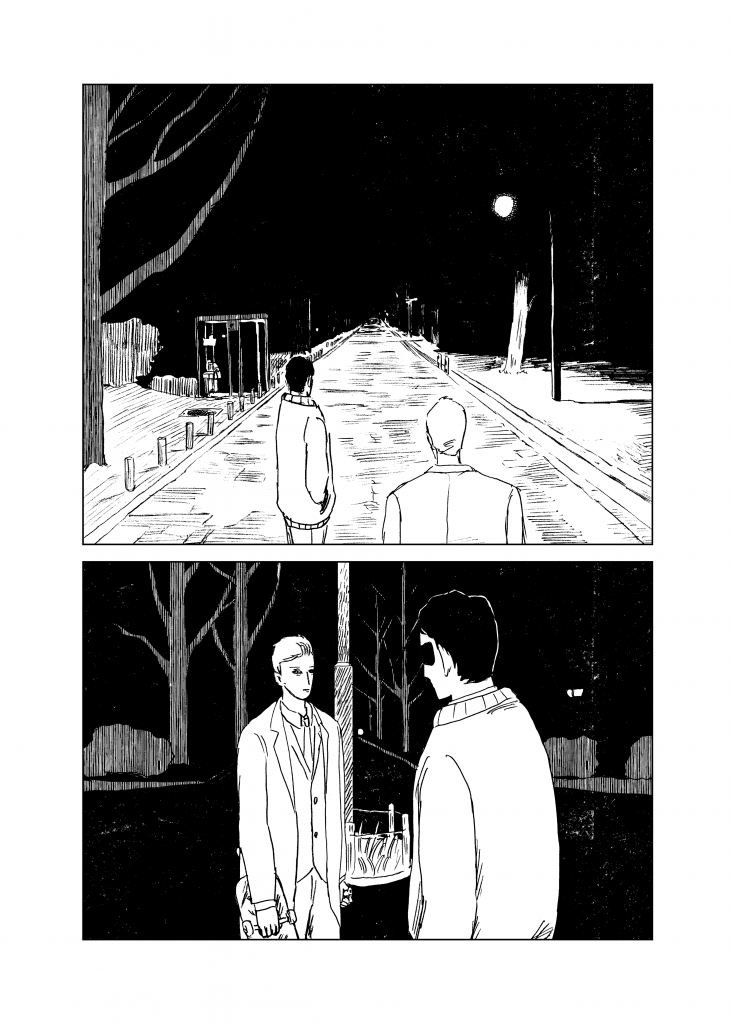

Masumura’s art is sketchy and wispy, the figures delineated with delicate thin lines floating in stark white space. There’s a deliberate imprecision to the drawing, which in some panels gets stripped down to cartoony basics, but Masumura’s character designs are iconic in their simple way. They get a lot of mileage out of flourishes like the black oval that inexplicably covers the center of Hajime’s face. It’s tempting to read this mark purely as a visual metaphor for Hajime’s failure to fit in, but, if so, it’s a metaphor that bleeds into the world of the story itself as other characters casually reference it to distinguish him. It’s a great example of the way Masumura balances designy minimalism with naturalism.

The stripped-down quality of the art also contributes to the claustrophobia of the setting. As Hajime’s cousin Minori angrily points out, lambasting Juichi, none of the characters are as stranded or as isolated as they feel or as the book makes them out to be. Though Masumura never allows much of a glimpse of the world outside Marigaoka, the characters are actually in Tokyo, a short subway ride from its more bustling sectors of business and entertainment. It’s only their own inertia, and the constricting boundaries of the art, that fences them off so completely from the outside world. The spaces of Marigaoka are drawn empty or sparsely furnished, particularly the café Juichi runs, which is just a big lonely rectangle with a couple of tables at its edges. A few simple shapes sketched with fragile, fading lines can stand in for the entire background of a scene.

In particular, Masamura draws Juichi with an economy of detail that’s central to how the character is perceived. He looks like a childish caricature of a businessman in his unblemished suit that’s too big and hangs limply on his gaunt body. It’s the only outfit he ever wears. The immaculate cleanliness of that suit makes it read as pure white, ostentatious, and distinctive, as unmistakable a marker of his identity as Hajime’s black mask. With his boyish flop of hair, blank eyes, and that very simply rendered suit, Juichi seems to be playing dress-up, which on multiple levels of course he is.

Juichi is hiding the core of himself behind that slick exterior. He’s smart, but won’t admit it, reading philosophy books in secret, carrying a few pages at a time to read in spurts when he thinks no one is looking. He’s also projecting a gangster aura that’s not really backed up by his actual activities. He’s obviously low in the yakuza hierarchy, an errand boy, even as he tries to act the part of the benevolent godfather for Marigaoka’s elderly residents. Only in private, with Minori, does he ever express himself in anything but the most banal small talk. Just as the people in town see the mark of difference literally written onto Hajime’s face, they must see Juichi as inscrutable and vague, roughly sketched into reality. He’s barely a person, the lines of his body just about holding together, only as recognizable as the suit he wears.

The minimalism with which Juichi and most of Marigaoka are defined is very deliberate, and Masumura can draw in more detail when they want to. The nighttime scene-setting panels of quiet buildings with a few lights shining look like fuzzy nth-generation xeroxes, crafted with precision even when much of the detail gets washed out in expanses of inky black. Masumura draws key details, like the creepy masks worn by a rival gang, with a greater density of shading and more intricate linework than most of the rest of the book, making them stand out viscerally from the surroundings.

These disjunctions pop up periodically. Although the atmosphere is mostly quiet and reserved, as the characters stoically drift through their lives on the fringes, sudden violence and frenetic activity can erupt from that surface calm, boldly expressing the inner desperation that the town’s youths keep submerged the rest of the time. In one of the most startling scenes, a fight breaks out between Juichi’s crew and their rivals, triggered by Hajime’s disrespect of the opposing leader, Toriumi. When Toriumi breaks Juichi’s jaw, Masumura draws it as a stylistic rupture of the actual surface of the comic: in a huge showcase panel, Juichi’s mouth elongates comically and disturbingly, hanging slack and stretching out in an unnatural yawn. It’s one of the rare moments when the Scorsese-esque violence bursts dramatically to the surface. But those feelings, and the raw rage that permeates the story, are always present, shaping and deforming the very lines that construct the characters.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply