“I don’t know who I am anymore,” a friend Tweeted in July in reference to Belize’s almost year-long curfew (previously 10 pm, now 9 pm) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. After rolling my eyes for a minute, I realized I’d been hearing similar sentiments among other single folks in their twenties and thirties in the past two years. A peculiar loneliness echoed in those feelings, the absence of nights without mystery or thrills had similarly done me in, depriving me of chances to show off dance moves, meet a stranger’s eyes across a bar, or share a quick word with someone I wouldn’t talk to again. The pandemic and its resulting regulations exposed how these nights of the id played their own role in sustaining a sense of well-being for me, instances that reveal that, in spite of the scale of our unimaginable horrors, there are others also sharing a longing for mundane euphoria. Someone calling our name in a crowd. An offer to buy us a round. An outstretched hand to steady us when drink and the vibe sending us careening to the ground. “Telephone, Sleep, Music” by Kawakatsu Tokushige illustrates the malaise of searching for such connections in a pre-COVID world where, despite missed attempts, people somehow still found themselves back on the same dancefloors, seeking some discontinuity from their routine to make life momentarily memorable amid the blurring passage of time.

Notably, “Telephone, Sleep, Music” is a study in the quiet failure to achieve connection one night at a Tokyo dance club. This is not the story of a night of shenanigans where everything goes to hell for a moment before coming out right in the end. Nothing is really learned by the main character, Miyo, other than a reaffirmation of the struggle for fulfillment people have always faced when out on a night alone, blowing money on covers and drinks in the hopes that this time something will happen. Yet, towards the end of Miyo’s night, she reflects on the mundanity of these nights out, how they lead to “…Instances when [she] feels like [she doesn’t] hear anything anymore. And when that happens, the boundaries between things begin to blur.” “Telephone” is the first comic I’ve seen that gets that sense of hazy recollection that accompanies those futile moves among loud rooms, like opening the fridge five minutes after checking it and hoping there’ll be something good in there the next time.

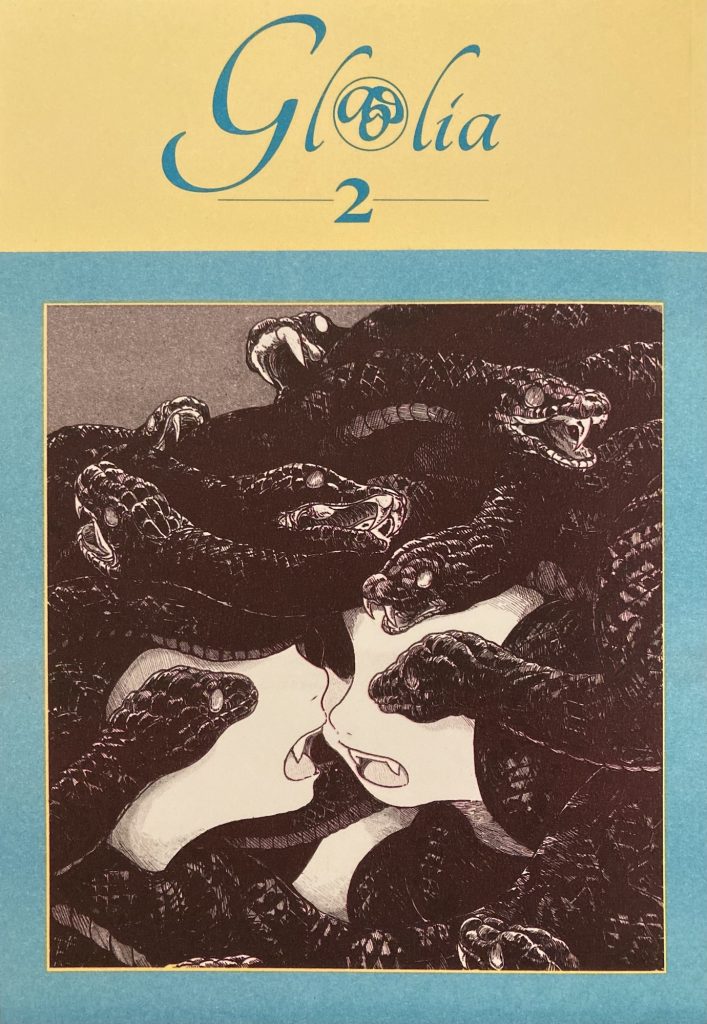

Risograph-printed by Cold Cube Press and published by Glacier Bay Books, the Ignatz-nominated anthology Glaeolia 2 in which “Telephone, Sleep, Music” is included, was released in November 2020. Volume 2 is 80 pages longer than its predecessor and has two returning artists from the first volume, Mori Masayuki, volume one’s cover artist, and “Telephone”’s artist Kawakatsu Tokushige. Glaeolia 2 offers exactly what I was seeking to broaden my knowledge of non-Western comics, an anthology of short-form manga by mostly self-published artists working outside of mainstream tastes. And amid the many stories offered up therein, Kawakatsu Tokushige’s “Telephone, Sleep, Music” was the one that I’ve returned to repeatedly since, ruminating on the nature of solitude, the vague goals of a night out, whether baths are gross or lovely, and the doldrums of being in your early 30’s with a semblance of stability but no further momentum.

In “Telephone,” the central character, Miyo, seems to be alone whether she’s having an extended bath, talking on the phone with a friend, or shuffling through a crowded dancefloor. We first see her on the title page, head down and away from the reader, seated in a swivel office chair almost teetering off the seat, steadying herself with her hands. It’s an image that conveys the sensation of boredom and anticipation that follows a long work week when you’ve returned home itching to do something, but you haven’t sorted out any plans with anyone and you’re considering maybe just calling it a night because the alternative feels too out of reach, too abstract to be worth the effort of getting cleaned and dressed.

One of the longer pieces in Glaeolia 2, “Telephone, Sleep, Music” nevertheless features very little plot over its 51 pages. What we get here instead are snippets of mundane conversation and attempts to dissolve into a crowd through drinks and dance. Its lack of urgency is what I most appreciate about this story: Tokushige’s interest in using several pages to portray an unremarkable and decidedly non-sexualized bath, taking us through each step and then repeating this pacing for almost every other experience in this story, gives you the sense that you’re almost experiencing the night in real-time, or, more accurately, a remembered version of the night. There’s poetry to this type of intimate portrayal, the attention given to moments that we might toss off as unremarkable the next day but comprise the majority of what it can feel like to be alone in a crowd.

Despite the seeming lack of overall satisfaction with the night’s events, there’s an enviable quality to the main character’s encounters: her ease moving through Tokyo’s trains and sidewalks, the inconsequentiality of her encounters, and the overall lack of dread when surrounded by others in tight spaces. Readers hardly learn anything about Miyo’s interiority — why she’s going out on this particular night or what she hopes to encounter. Events outside the main narrative are occurring: a fire we never learn much about and the dissolution of her latest romantic fling, but the comic treats these as events that merely happen to have occurred rather than anything on which we should actively ruminate.

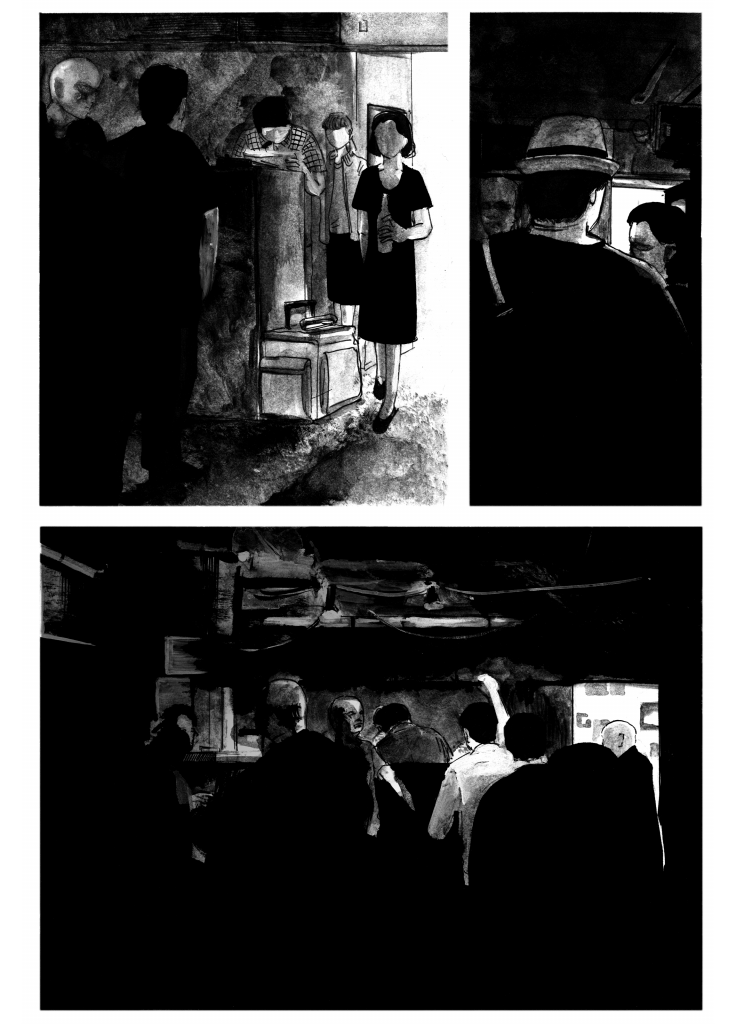

Tokushige is more invested in conveying the effect of Miyo’s uncertainty about what she’s doing with her night, moving through the space sipping on Heinekens without ever really engaging in anything that’s going on around her beyond polite attempts at listening to men talk at her. Her night mirrors much of my own time hanging out in bars and nightclubs, seeking connection, straining to hear every other word of a stranger’s anecdote, and leaving just as others seem to be gearing up for the next round of activity. Still, there’s a real sense of community among Miyo and the other characters (albeit one centered on getting shitfaced and thrashing to early morning sets) that I want more than most other things presently. Tokushige changes the visual style of the story over the course of the night as the protagonist downs Heinekens and shots offered by fellow revelers. People lose detail and mesh with each other mirroring her drunkenness and altering her and our perception of the night’s events, showing us how little each encounter matters on its own and that the atmosphere is what they’re more interested in conveying. Even prior to Miyo’s altered state, Tokushige breaks from the story’s established style to more impressionistic imagery, excluding facial features or bathing a scene in dense stylistic shadow, giving the sense that we’re watching a memory in the process of being forgotten.

This isn’t a story interested in obvious climaxes. Rather, the night culminates with the character asleep on a chair at the dancefloor’s perimeter only to be awakened by a friend gently letting her know the party is over. Maybe that’s what I most miss as we’re now more than midway through year two of the pandemic in Belize where police statutory instruments and a third wave sustains that isolation between folks, preventing opportunities to forget myself in a crowd with friends, comrades, and strangers. Emerging with others into the early morning, Miyo contemplates her age and remembers that she’ll have to take the trash out when she gets home. The comfort of the mundanity that awaits us is all that comes up along with the sun and percolating hangovers. How I hope not to take that moment of reemergence into the sun for granted again, knowing that I likely will. “Telephone, Sleep, Music” gets what it is to yearn and to be unsatisfied with what’s presented, and yet, inevitably, desire revives itself and we enter the clubs again to merge into the mass.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply