The delightful cartoonist Alec Longstreth is an industry unto himself: a long-time creator and publisher of mini-comics, zines, and books, a frequent colorist of other cartoonists’ work, and Professor and Director of Academic Outreach at the Center for Cartoon Studies. His Phase 7 comics zine, which aims to be a lifelong project, has run since 2002, yielding twenty-three issues to date, and he’s been serializing Isle of Elsi, a free webcomic for young readers, since 2016. Consistent across all his work, from the more adult-oriented, sometimes autobiographical tales in Phase 7, to the frolicking fantasies of Isle of Elsi, and even the melancholy graphic novel Basewood, is a sense of comics-as-play: the work is tricky, often visually dense, and invites interaction. Frankly, it’s geeky. At its best, it’s about the joys of cartooning, yarn-spinning, and sharing (tongue-twisting too, sometimes). Reading Longstreth, I confess, I seldom feel stressed, driven, or afraid, but instead sort of pleasantly waylaid, as if I’m visiting someone else’s idyll. The work exudes pleasure.

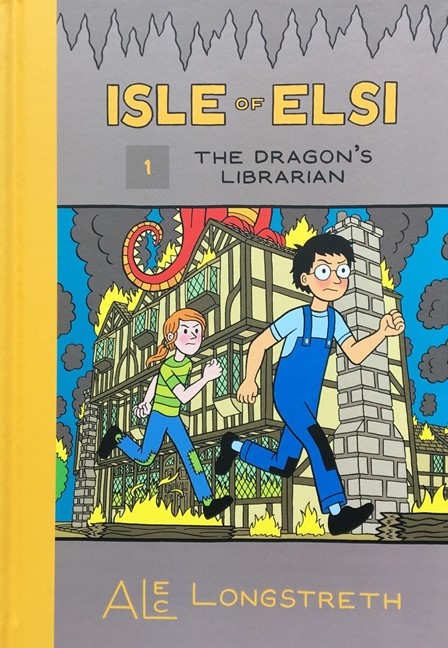

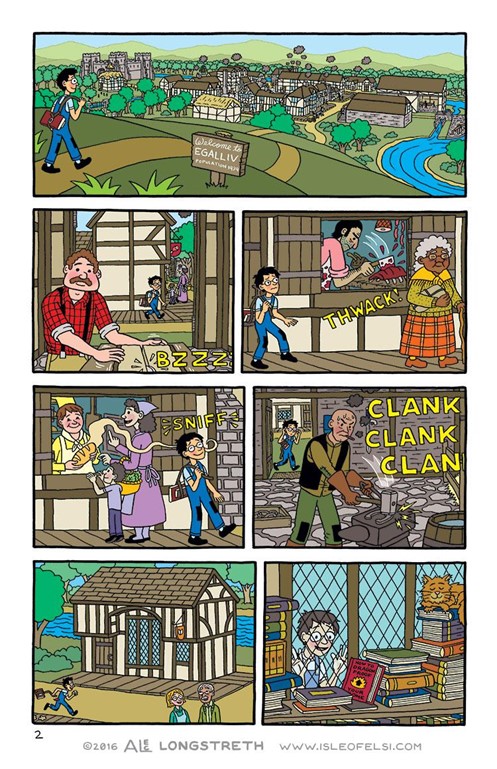

The Dragon’s Librarian is all about pleasure. It’s the first Isle of Elsi collection: a handsome, full-color, 144-page hardcover, self-published by Longstreth under the Phase Seven Comics banner. A Kickstarter project, it arrived in Fall 2019 and started filtering out into the world soon after; I first saw it last spring (I call it one of my favorites of 2020, so sue me). Its setting is the village of Egalliv, a generic, European-style, premodern fantasy town, replete with half-timbered mock-Tudor buildings (everywhere), a surrounding wood and streams, and all the signs of a bucolic yet industrious community: blacksmith’s shop, butcher, baker, general store, lumber mill, and so on. This story-world is governed, I think, less by a strict logic (anachronisms abound) and more by the desire for a wide-open playing field in which kid characters can explore, invent, and save the day. Puns, backward spelling (shades of Fred Guardineer), and other wordplay not only mark but practically define this world. Quips, malapropisms, and benign absurdities are omnipresent. As I said, geeky and pleasurable.

Isle of Elsi is eminently readable, clear, and sharp, with a diagrammatic neatness and flat colors that recall Tintin (a formative influence on Longstreth). Tellingly, Egalliv is architecturally precise, even a bit fussy, and graced with scenic and social details—yet the trees that hem the village are more notional than specific: flat-green puffballs on flat-brown stalks. Bricks, cobbles, and beams are patiently rendered but impossibly clean. Rainfall is absolutely vertical: tight patterns of small blue streaks. Emanata have a meticulous, standardized quality, more like clip art than calligraphy. Even when the protagonists get scuffed up, even when their clothes are patchy and worn, everything looks pristine. Gone is the super-dense crosshatching of Longstreth’s Basewood, replaced by crisp, vivid colors. Knee shots, waist shots, and scenic long shots predominate; the staging of action is more like that of a gag strip than an adventure comic book, though there’s plenty of roughhousing and rushing about. Longstreth’s four-tier layouts evoke Cark Barks (another influence), while crowd scenes have the density and clarity of Don Rosa (or Martin Handford’s Where’s Waldo?), with each character distinct. If the drawings sometimes tend toward an almost aseptic cleanness, their hand-made nature (including hand-lettering) keeps them lively and charming. The characters are expressive, and the prevailing mood rowdy.

The Dragon’s Librarian collects comics serialized in 2016-2018, including the long title story – a graphic novel-length fantasy with ironic twists influenced by Kenneth Grahame – as well as two shorter follow-up tales. There’s also a wealth of back matter, including a revealing behind-the-scenes section (readers who dig the stories will probably also dig Longstreth’s notes on process). The tales work with familiar ingredients: precocious boy hero Rex Jargon, Junior (“R.J. Jr.”) and his plucky friend, plus a wizard, a dragon, hardy townsfolk, and so on. Despite bullies, bandits, and the dragon’s depredations, despite losses and shocks, there’s little sense of danger or raw pathos, but, instead, a rollicking sort of action with many plot twists, some of them baldly telegraphed. In short, this is a game-like and bookish romp.

Longstreth’s story-world will be familiar to readers who know much of anything about post-Victorian fairy tales or Oxford School fantasy. Again, its ingredients are well known, even shopworn. But he isn’t trying to craft a Tolkienesque epic à la Jeff Smith’s Bone – that’s not his beat. Isle of Elsi lacks Bone’s layered world-building and avoids the messy, conflicted feelings rehearsed in, say, the Walker Bean books (by Longstreth’s friend and collaborator Aaron Renier). Instead, Longstreth aims for reflexive playfulness, recalling the nonsense of Edward Lear (another of his favorites) and perhaps The Phantom Tollbooth – texts that exhort readers to delight in words, sounds, and ideas for their own sake. Reading Isle of Elsi is more like a rule-governed activity (again, I think of Handford) than like committing to a long and arduous quest. It’s preciously old-fashioned and quirky to the point of being semi-autobiographical. Happily, Longstreth has taken steps to diversify his cast and open out his fantasy world to others (he could do more in this area, and hopefully will). Basically, the Tudor Revival setting and familiar fantasy tropes become set dressing for puzzle narratives that are about learning and thinking.

I greatly enjoyed reading this book, which reminded me of how delicious Longstreth’s work can be. I hope he will continue Isle of Elsi for a long time, with the occasional collection to mark the webcomic’s progress. The more recent stories (still uncollected) add emotional heft, social complexity, and some hints of menace to his world, but the geeky quirks remain. Refreshingly, Isle of Elsi ducks contemporary story formulas and has the eccentric zest of a true labor of love.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply