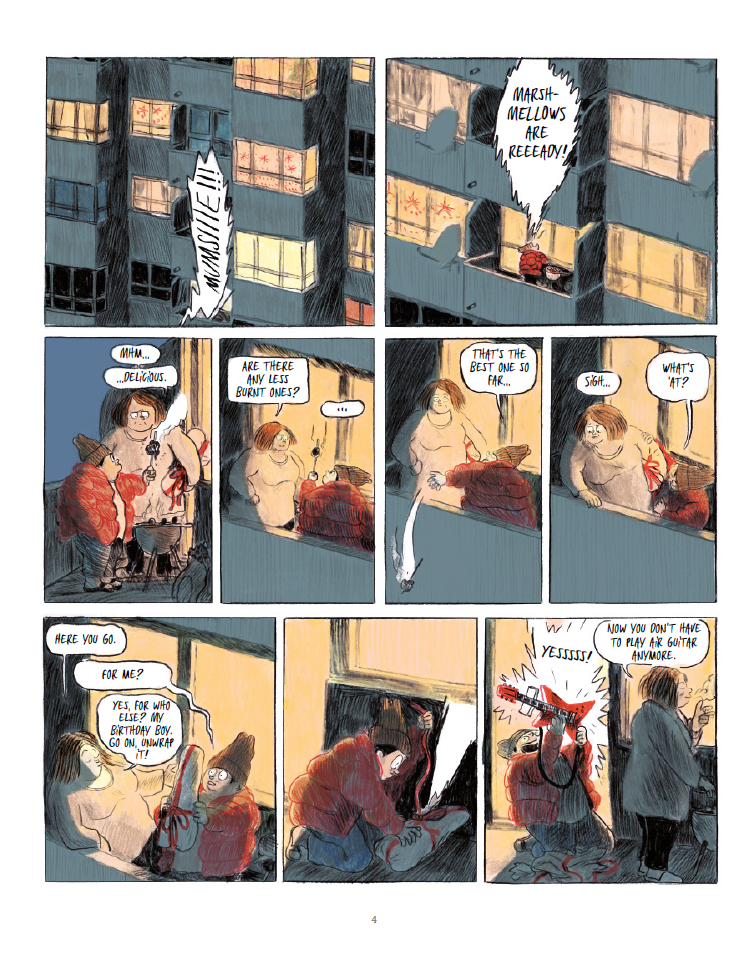

The Thud follows a young man named Noel who shares an apartment in Berlin with his mother. Noel is a type of young man often mistaken for even younger by those who don’t know better. He has a distinct way of looking at and talking about the world. He drives his mother a bit crazy, but she loves him. She takes care of him. Noel, it seems, needs taking care of; for him, some of the practical details of the world are a bit opaque. Though he has his own resources and skills, ways of remembering and doing, Noel’s outlook is the sort of outlook that people persist in comparing to that of small children. He is (as we say, as this book’s jacket says) developmentally disabled. Noel craves repetition, makes associative leaps that others cannot easily follow, and sometimes drifts into fantasy to make sense of things. His mother gets him. She is his anchor.

The “Thud,” though—the Thud changes everything.

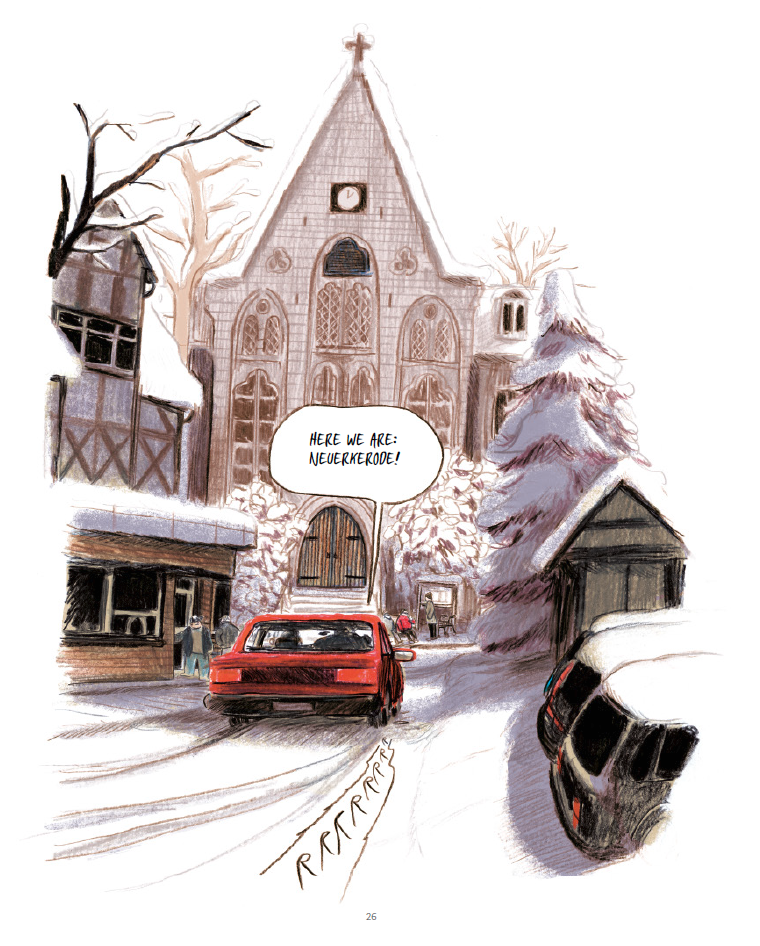

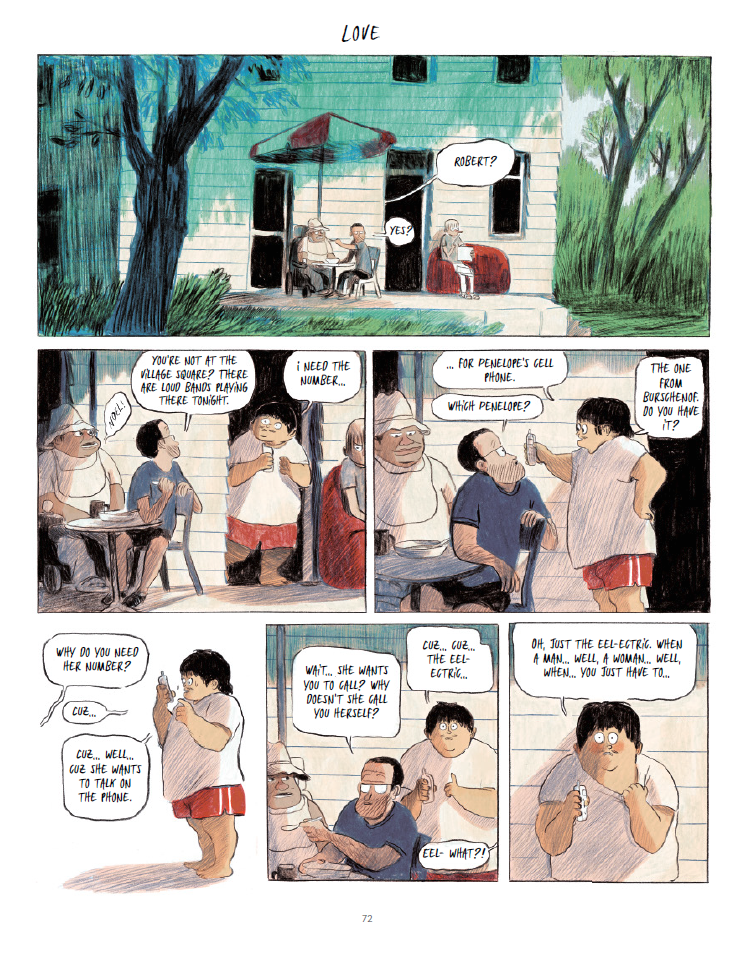

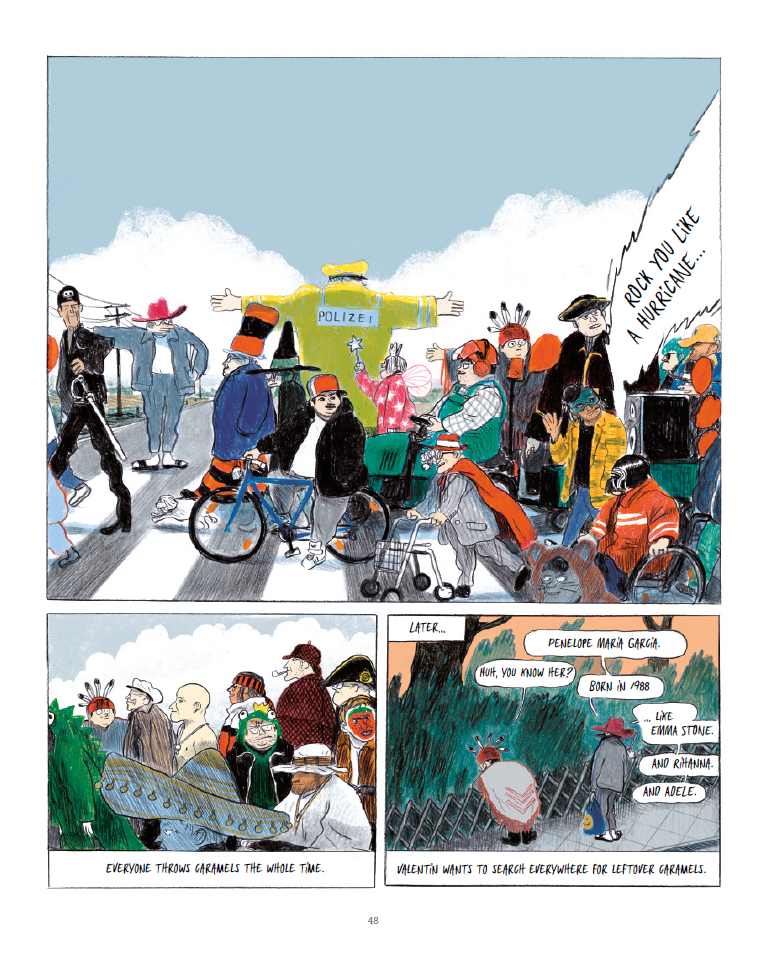

The Thud is the sound of Noel’s mother falling over, felled by a stroke, and hitting her head: the great crisis that splits Noel’s life into a Before and After. The Thud brings Noel’s mother to the hospital, where she is placed in a coma. Noel is lost. He has no one else in his everyday life to take care of him, and so he is shuttled to Neuerkerode, a planned community in Lower Saxony, about two to three hours’ drive down the Autobahn. Noel doesn’t acknowledge—perhaps he doesn’t see it this way—that Neuerkerode is an inclusive village for persons with disabilities (it’s a real place, founded in 1868). There Noel grows and changes, while still holding out hope that his mother may revive and restore their life to what it was. Hope is stubborn and slowly takes new forms. In the meantime, Noel builds relationships: with fellow villagers Valentin, Penelope, Irma, and Alice, with caregiver Robert, with various folks. These constitute a new life.

The Thud, written and drawn by German cartoonist Mikaël Ross, is a slender (128-page) graphic novel about friendship, attraction, misunderstanding, infighting, and solidarity – in short, about social life – among a diverse group of disabled and marginalized people, filtered through Noel’s understanding. First published in German as Der Umfall (2018), meaning “the accident” but also with a suggestion of “falling over,” the book has been translated into a handful of languages. Its French title, Apprendre à tomber (2019), means “learn to fall.” Der Umfall garnered the first-ever Berlin Comic Scholarship in 2018, and a Max and Moritz Prize in 2020. It is a much talked-about book. The impeccable English edition, The Thud, is from Fantagraphics, its arresting new title courtesy of translator Nika Knight (who has previously translated or adapted books for New York Review Comics and Seagull Books).

Informed by Ross’s experiences with the citizens of the real-life Neuerkerode, The Thud envisions its disability community in a complicated yet affirming way that balances the sentimental and antisentimental. Ross avoids the cliché of savantism – the compensatory fantasy that developmentally disabled persons must have superpowers unappreciated by ordinary folk – and mostly skirts around the Romantic idea that much madness is divinest sense. That is, despite a few fantastical scenes, Ross sidesteps the association of neurodiversity or cognitive difference with the Romantic sublime. Blessedly, there is no “wisdom” of the disabled or different here. The Thud is largely a tender comedy, mining saltiness and humor from the odd connections that Noel and others make, and from their ways of banging up against each other.

The Thud is Noel’s coming-of-age story (and, in fact, is billed as a Young Adult book) but with enough narrative doglegs to go beyond Noel alone. It is also, perhaps, an awkward love story—I mean, a story about courtship, about the slow dawning of mutual recognition between two people. But Ross is not so literal as to telegraph his themes. He keeps you guessing at what his characters might feel and do. Free from narration, and mostly free from knowing voices that would explain away the world that Noel and his friends navigate, The Thud walks a tightrope between pathos and reserve—or between irreverence and the kind of respect that comes only when you’re willing to see fumbling human comedy in everyone around you. Ross’s depiction of Noel, and of life in Neuerkerode, has been greeted rapturously by some—I expect it will be criticized by others. It’s a gutsy performance: two parts matter-of-factness, one part visionary drawn fantasy. Me, I found it touching, funny, and gorgeous.

Aesthetically, The Thud is pure pleasure, rendered in pencil and delicately colored in what I took to be a blend of pencil and digital. Colorist Claire Paq is thanked (rather too discreetly) in the dedication and the back matter. My understanding, or best guess, is that Ross did much of the coloring himself, in pencils, then had blocks of Photoshopped color added for many backgrounds. I am supposing that this is where Paq came in, and crucially. Ross told an interviewer from Der Tagesspiegel that the digital coloring served to “calm down” (beruhigen) what would otherwise have been overbusy pages—but that the process musste auch super schnell gehen, that is, also had to go very fast. As is often the case with comics, what served to streamline the production and aesthetically “calm” the finished pages also helps with readability. In any case, Ross and Paq often let the bare whiteness of paper show through, and many page grids are broken up by small borderless images, usually sans backgrounds: cameos or little climaxes that let the pages breathe. The design sense is traditional and rectilinear—almost always a matter of three even tiers—but those open, unbordered moments of punctuation are a kind of sweet relief. In general, Ross’s style inclines toward the caricatural freedom, but also the light touch and understatement, of artists like Joann Sfar, Lewis Trondheim, or admitted influence Christophe Blain, whose mix of lively figures and rustly lines with painterly color seems to be Ross’s ideal. The result is a vigorous, at times rude cartooning that still retains sensitivity and a sense of mood. Among other things, The Thud is a library of vivid expressions, big gestures, and feats of atmospheric coloring.

As a writer, Ross is observant and impish and indulges the odd profane moment. One scene shows Noel and Valentin learning about sex by watching porn. They look stunned. The porn stays off-panel, though, and so the scene captures, in miniature, Ross’s balancing act between bluntness and discretion. The Thud threads carefully between amused matter-of-factness and quiet watchfulness, ribald business and humane warmth. Knight’s translation manages to be elegant and raw at once, and never stilted; it has its own peculiar word bank (words favored by Noel and friends), verbal echoes, and distinct character voices. The script never hides the Germanness of the setting, yet Knight’s English dialogue is lived-in and believable.

Besides questions of pleasure, there are others we should ask. Judging a book like The Thud should include an ethical as well as aesthetic dimension. Frankly, stories like this present a quandary, as the world is already rife with works depicting disabled persons from points of view explicitly or implicitly different from their own, points of view that privilege a normate, presumptively “non-disabled” framework. So many disability stories are created from a stance apart. Disability theorists are familiar with David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder’s concept of narrative prosthesis: the recognition that disability, far from being culturally invisible, continually serves as a prop, occasion, or justification for various kinds of stories—fantastic or realistic, horrific, satirical, or sentimental. These stories are only rarely self-representations. Storytellers (we) can’t seem to stop using disability as a device. The Thud does not evade this problem; what it offers is more like a well-intended “representation of” than self-representation.

(An intriguing alternative is modeled by another book of comics, Match de catch à Vielsam, published by Frémok in 2009, in which known comics creators co-author stories with collaborators from an art center for persons with disabilities. Tellingly, that book envisions collaboration as rough sport, a “wrestling match.”)

In a way, The Thud is a monument to charitable good intentions. The book was commissioned by the institution that maintains the village, the evangelischen Stiftung Neuerkerode (Evangelical Foundation Neuerkerode), for its 150th anniversary. Therefore, it officially began not as Noel’s story but as an act of institutional commemoration, at least from the Foundation’s point of view. Ross came in as a commissioned hand. Reportedly, he researched the book for more than a year while maintaining a flat in Neuerkerode and spending days there intermittently, every few weeks. He came not as a disabled-identified person but as a visitor seeking to learn things, with the book project always on his mind. Though Ross has acknowledged drawing story elements (such as Irma’s memories of Neuerkerode under the Nazis) from real events, and even building characters by conflating real persons, The Thud appears to be more or less fictive, thus untethered from the obligation to retell precisely the stories of actual people and encounters. So: The Thud is a fiction of disability, prompted by the varied motives of its institutional sponsor and the artist who created it.

Based on interviews (Ross’s website gathers a bunch), the book’s backstory appears complicated. Ross came to the project conscious of being an outsider and does not identify as disabled, yet he takes the designation “normal people” with a dose of skepticism and dislikes the reflexes of pity or mystification that tend to mark normate depictions of persons with disabilities. Further, it seems that Ross has his own nuanced, non-idealized view of Neuerkerode and was essentially given carte blanche to develop his story his way. All this is purely implicit in the comic, of course, as The Thud does not explain much.

Ross’s choice to focalize the story through Noel, to create what he has called einem Perspektivwechsel (a change of perspective) for readers, has a complex twofold effect. On the one hand, it makes The Thud more ambiguous and open and allows for perplexing, unresolved moments and startling effects, such as Noel’s occasional dreamlike visions. Apart from a few instances of caregivers using terms like “epileptic seizure,” what happens in the story is not authoritatively explained to Noel—that is, not reduced to rationalizations. The book invites readers to lean forward and do some work. Without turning Noel’s disability into a prop for Romantic obscurantism—again, cliched evocations of the disabled sublime—Ross is content to let some mystery remain. This is aesthetically interesting. Secondly, maybe more negatively, the book’s Noel’s-eye-view prevents us from knowing answers to some basic questions, such as: To what extent, if at all, is Noel legally autonomous? Who decided that he should go to Neuerkerode? Does he stay there voluntarily? What are the horizons of his future life (for that matter, how did the other citizens of Neuerkerode come there, and why do they stay)? These questions are not narrativized but only hover implicitly around the story, without interrupting its poetic evocations of place and persons. As a story, The Thud works like magic; as an account of how things might really be in Neuerkerode, it is, perhaps unavoidably, incomplete.

I find myself wishing that The Thud had come out in time for my most recent “Disability in Comics” seminar (last fall). I would like to know what my students would have made of it. My guess is that they would have asked some of the same questions I am asking, but others too—and that I’d have learned a lot from their responses (I always did). Conversations in that course tended to make me conscious of my own positioning as a reader—of the things I take for granted and things I overlook. The Thud does that too. I come to this book conscious of being part of a neurodiverse family that includes several educators, a family in which conversations about disability are necessary and frequent. For most of my life, I have been partnered with a Special Education teacher who works hard to uphold students’ right to meaningful choice, a teacher for whom social interdependence and access to community are guiding principles. These things, as much as my love of comics, inform my interest in graphic depictions of disability. I suppose that is why I think The Thud is a courageous book—but, of course, my perspective is limited. I can see that The Thud has the defects of its virtues: it is elliptical, poetic, and in the end, perhaps befitting its status as “YA,” hopeful, affirming, and borderline Romantic. But it’s also pretty damn good.

I don’t want to hail The Thud as a representational victory or claim that it sidesteps every problem it poses. That wouldn’t be interesting—and we should be wary of burdening books with the expectation that they will be ideally representative. No book can bear up under that. But, taken as both Noel’s story and a hint of what Neuerkerode may be, The Thud is insinuating, artfully complex, and lovingly rendered—an eminently re-readable story of a person and a place. Again, I would love to be in a room full of people talking about, debating it, digging into it.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply