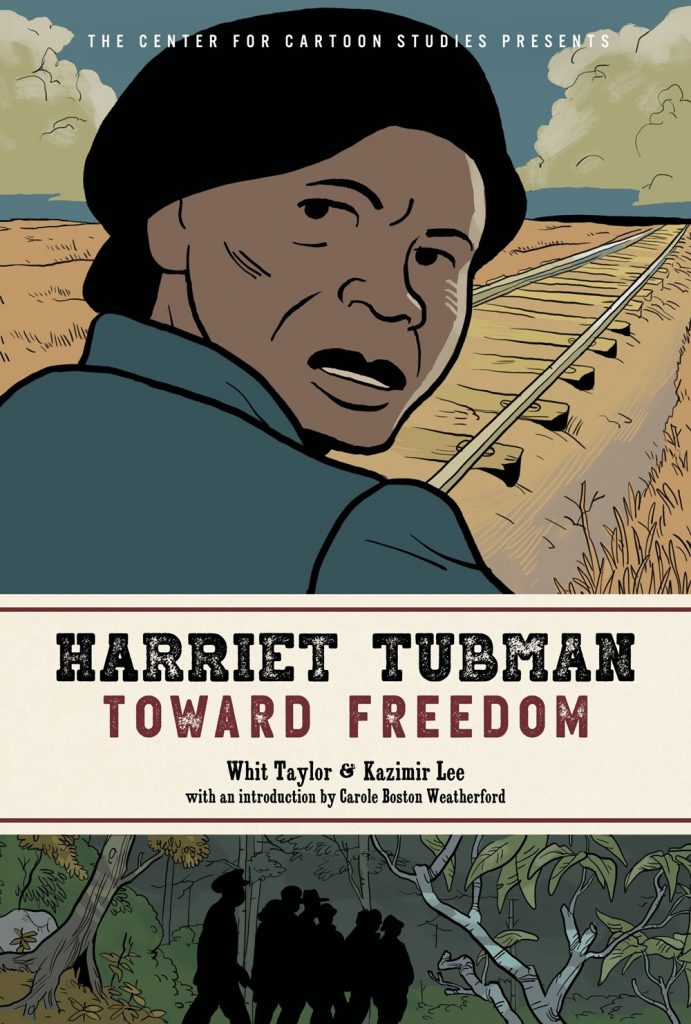

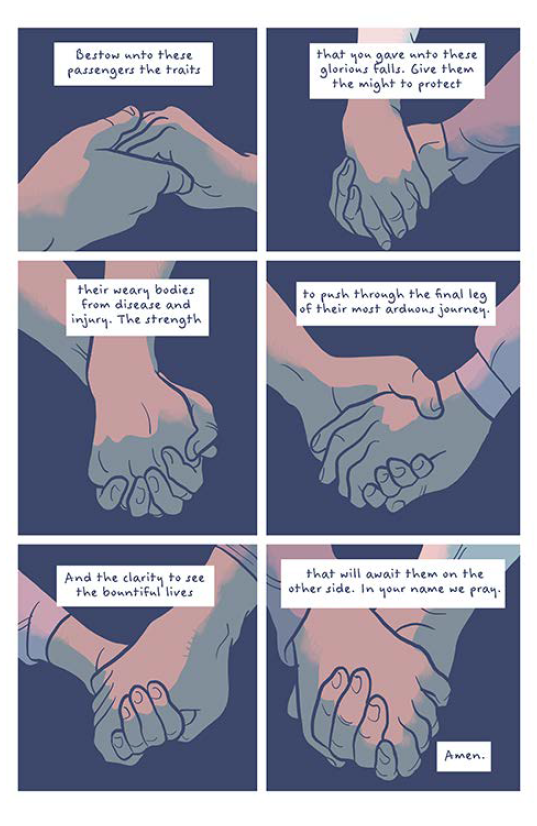

Harriet Tubman: Toward Freedom is about escaping slavery—which, the book acknowledges, is but the first step in learning “how to feel free.” Yet it is also about giving and accepting, about gifts given and received. Noticeably, the book focuses on hands in the act of giving and taking. I count more than a score of panels that give close-up views of hands: touching, offering, holding out notes or letters, breaking bread, healing, doing service. Co-authors Whit Taylor and Kazimir Lee focus on quiet exchanges and touches, on gifts borne by hands, rather than historical sweep or summary. This tendency reaches its peak with a page of hands clasped in prayer:

This page epitomizes a great strength of the series to which it belongs, that is, the series of biographical comics edited by James Sturm and published under the banner “The Center for Cartoon Studies Presents” (launched at Hyperion in 2007, now continued by Little, Brown). These graphic novellas, which typically clock in at about 100 pages, do not try to be sweeping or comprehensive. They do not set down facts about a life in a strictly chronological, literal, and exhaustive way. They avoid burdensome recitations of detail. Instead, they are compact and focused, revealing lives through telling incidents or core conflicts. The books are judicious, selective, and dramatic, reading less like conventional juvenile biographies and more like plays based on fact but artfully compressed. Because they are not overcrowded or over-dense, they have the rhythms of good comics. A few pages of expository back matter (“Panel Discussions”) suffice to give context and point readers toward sources. The main thing is for the stories to work as stories. The results avoid the dry expositive style of middle-grade biographies that seem designed to prop up school reports; at the same time, they attain a greater narrative complexity than most biographical picture books (which of necessity squeeze lives into very small packages).

Toward Freedom is no exception: it reserves details about Harriet Tubman’s childhood and family tree for the back matter and concentrates on characterizing Tubman as a visionary woman of faith, determination, toughness, and, then again, real vulnerability. Though the Introduction by Carole Boston Weatherford (author of Moses: When Harriet Tubman Led Her People to Freedom and many other historical and biographical books) promises a life story spanning “from the slavery era, the Civil War, and the Reconstruction to the women’s suffrage movement,” in fact Toward Freedom takes a smaller compass. It starts with Tubman as an escapee and free woman in Philadelphia in 1850, devotes less than a dozen pages to recounting her early life, and focuses on just one of her many missions: the rescue of three of her brothers and several other enslaved persons in December 1854. The story is spare and streamlined. Despite this, Toward Freedom reveals a great deal about the inhuman business of slavery, the culture and language of the enslaved, the abolitionist movement, the effects of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and the operation of the Underground Railroad that, over time, carried thousands of enslaved people out of bondage. Impressively, the book entirely avoids “suffer porn” and explicit violence, and yet the stakes feel very high. Though Taylor and Lee hint at the terrors of slavery, they emphasize resourcefulness, bravery, and fellow feeling among the enslaved.

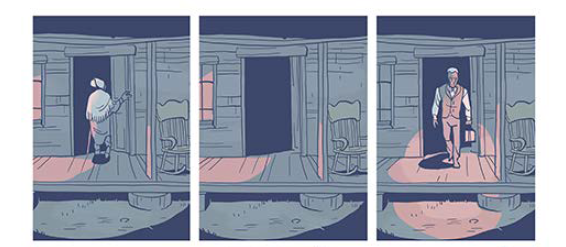

Excellent beat-by-beat storytelling — aided by Lee’s supple lines, beautifully uncluttered panels, and muted, minimalist palette (light mauve and cold blue-grey) — gives the narrative a dynamic rhythm and plenty of breathing room. Pauses, silences, charged close-ups, and Kurtzman-like triptychs dilating on subtle action impart an unhurried feel. Taylor and Lee capture both suspense and complex feelings (as when, for example, Harriet’s brother Robert wrestles with a dilemma: he must leave his wife and newborn child or else be sold off by slavers). Desperation, ambivalence, fear, and force of will come through vividly. Overall, Toward Freedom is a lesson in comic-book classicism, a graceful exercise in subtly rhetorical layout and pacing. It reads quickly yet invites gazing afterward.

Discreet, muted, and realistic, Toward Freedom avoids triumphalism and adventure genre tropes. It depicts Harriet as both a spiritual force and a gun-toting pragmatist who knows that she can carry her people only as far as the threshold of freedom. The ending brings Harriet, her brothers, and fellow refugees to St. Catharines, Ontario, yet the book has the wisdom not to present the flight to Canada as a panacea, nor the fight for freedom as a fait accompli. Instead, it ends in anticipation of the struggle and greater freedom to come—a good example of Taylor and Lee’s quiet power:

Simply put, Harriet Tubman: Toward Freedom is a fine book. Though my favorite volume in the CCS series thus far has been Joseph Lambert’s Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller (a book I never tire of touting and teaching), Toward Freedom belongs in that company. It’s a remarkable work of sympathetic imagination, aesthetic elegance, and subtle teaching, both a great comics experience and an invitation to dig more deeply into a harrowing and inspiring life.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply