On the first page of this road-trip chronicle, Whit Taylor sits with her husband in their car and marvels at the grandeur of the Montana sky:

Taylor: It’s gwahhhgeous! I’m making up words it’s so beautiful.

Greg: And look, a strip mall.

Taylor: I mean, it’s still America.

Throughout the story, Taylor appreciates the sheer beauty of western Montana while also acknowledging its scars, mostly of the sociopolitical or environmental variety. And whether describing the drive along the Louis and Clark Trail or grappling with what that expedition ultimately wrought upon native peoples and the environment, Taylor is good company. This is an intimate and relatable read with a lot of meat on its bones. For my money, it’s her best work since her 2015 graphic novella Ghost.

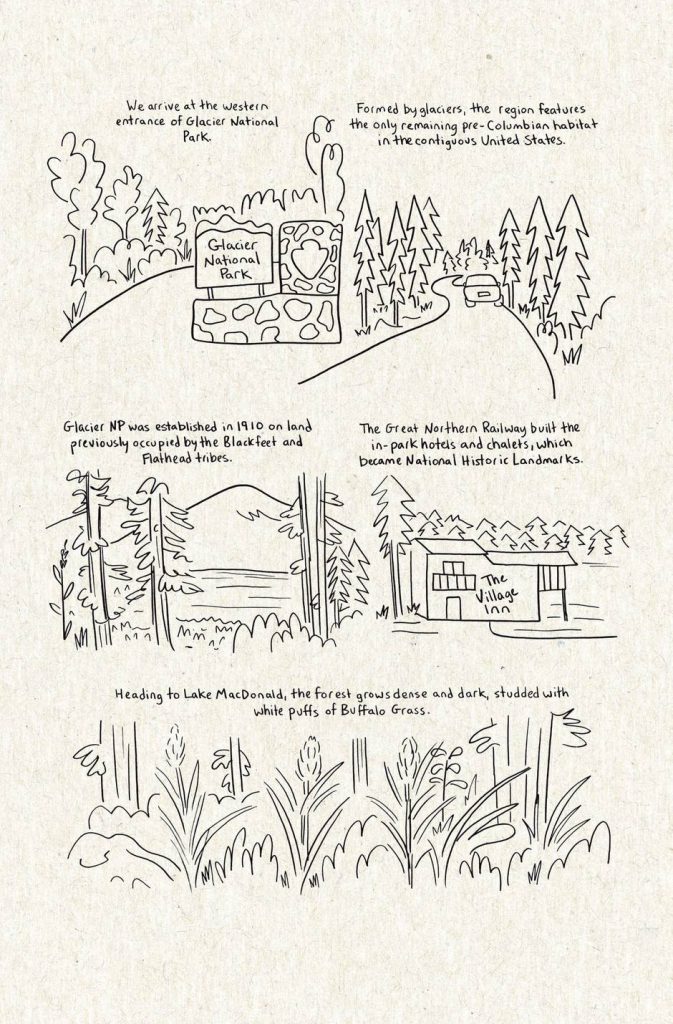

On the surface, Montana Diary is a straightforward travelogue, recounting quotidian vacation fun with clear-eyed observations about the state of things, generously sprinkled with historical factoids on everything from how the Glacier National Park was formed to how the state was acquired through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 (though it didn’t achieve statehood until 1889). Taylor has a particular talent for weaving this sort of information into her narratives without ever becoming pedantic, using it almost as anecdotal evidence to color responses to her surroundings.

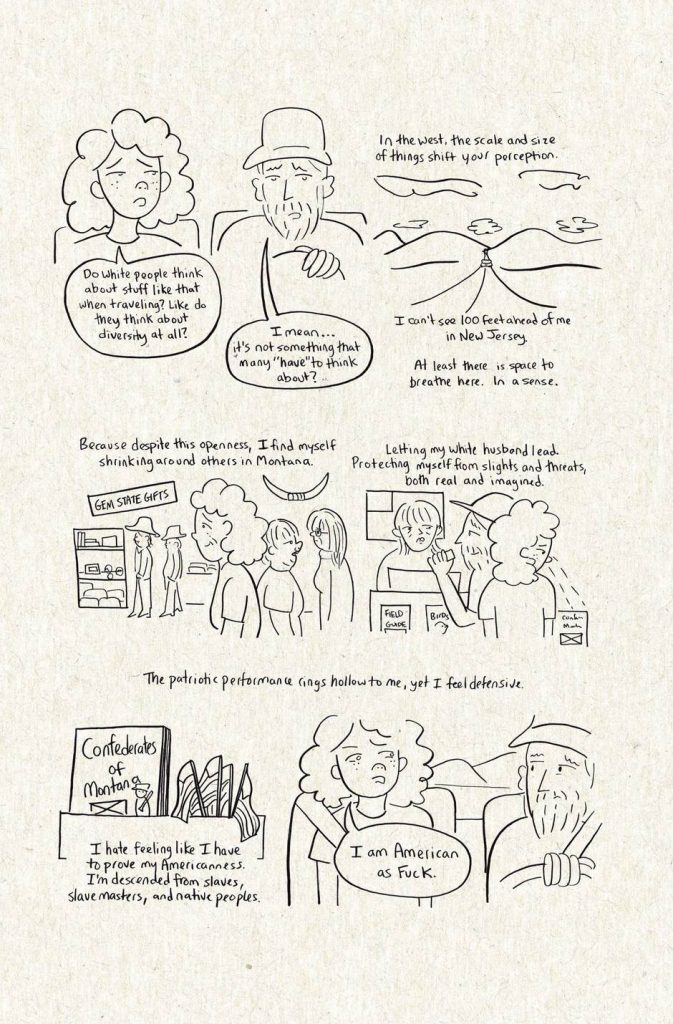

For example, in one scene, while browsing in a tourist gift shop, Taylor muses: “In the west the scale and size of things shift your perception. I can’t see 100 feet ahead of me in New Jersey.” To me, this encapsulates one of the major allures of travel: by getting out of your own space and into the unfamiliar, your senses take in all kinds of new stimuli, prompting a fresh perspective.

But Taylor, who is Black and married to a white man, also acknowledges this situation can bring out the fear of being in alien territory, triggered in the gift shop by a display of “Confederates of Montana” tchotchkes. She confesses: “I find myself shrinking around others in Montana (…) Letting my husband lead. Protecting myself from slights and threats, both real and imagined.” Taylor’s disquiet is well-founded: in addition to noting the store display, she points out that Montana voted overwhelmingly for Trump in 2016 and that the state is one of the whitest in the Union (she also reminds us that until 1967 it was illegal to be in an interracial relationship anywhere in the USA, a sobering fact). When you’re a racial or any other kind of minority in a conservative area, one’s identity alone can be enough to generate anxiety. Or at worst, becoming an actual target for hate.

Whit and Greg also visit the Museum of the Plains Indian in Browning, where a staff member informs them that the Blackfoot tribe is one of the few that was not kicked out of its ancestral lands by the U.S. government, because their land was not deemed “relevant” to government interests. As Taylor notes, the American mythos exalts exploration and innovation “at the expense of the exploited and the overlooked stories of those we’d rather forget.” But it’s all there, hidden in plain sight.

Another recurring theme in this work is humans’ uneasy relationship with nature. Taylor informs us right off the bat that one of her key reasons for going to Montana is to see the glaciers “before they melt.” Although she says this jokingly, when she overhears someone at Glacier National Park say that the glaciers “won’t be here for long,” Taylor feels real grief and helplessness, acknowledging that our personal decisions to mitigate climate change (i.e., recycling and such) barely make a dent in the scheme of things. It’s becoming increasingly clear that we’re losing the battle with reversing climate change, and the fact that people are flocking to see these natural wonders—while they still can—is heartbreaking.

In a more lighthearted vein, Taylor describes fraught encounters with wildlife and indulges in some sly self-satire. At Glacier National Park, the pair have a too-close-for-comfort encounter with a bear. Although this is serious business, Taylor’s drawings of her freaked out expressions are funny. Later in their hotel room, when discussing the incident, Taylor tsk-tsks people’s lack of “environmental literacy” in the wild (“We are in THEIR home”), but then immediately blows a gasket when spotting mouse turds on her bed, right by her pillow: “Why would they do this to us?!” Later on, even though they’ve switched rooms, Taylor is still fretting: “I hear you can get the Hantavirus from inhaling rodent feces…I took a nap on that old bed.” Greg says what any sensible partner says to defuse the escalating anxiety: “You’re not going to get Hantavirus.”

Whit and Greg’s interaction is one of the quiet strengths of Montana Diary. She captures their easy rapport with warmth and humor, with Greg often playing the straight man.

Taylor (having a craving): Ooh, Huck Shakes! Love a Huck Shake. It’s not too early for a Huck Shake.

Greg: Stop saying Huck Shake.

That got a laugh out of me; that’s me and my husband in a nutshell, especially on vacation. (By the way, Taylor does get her Huck Shake.)

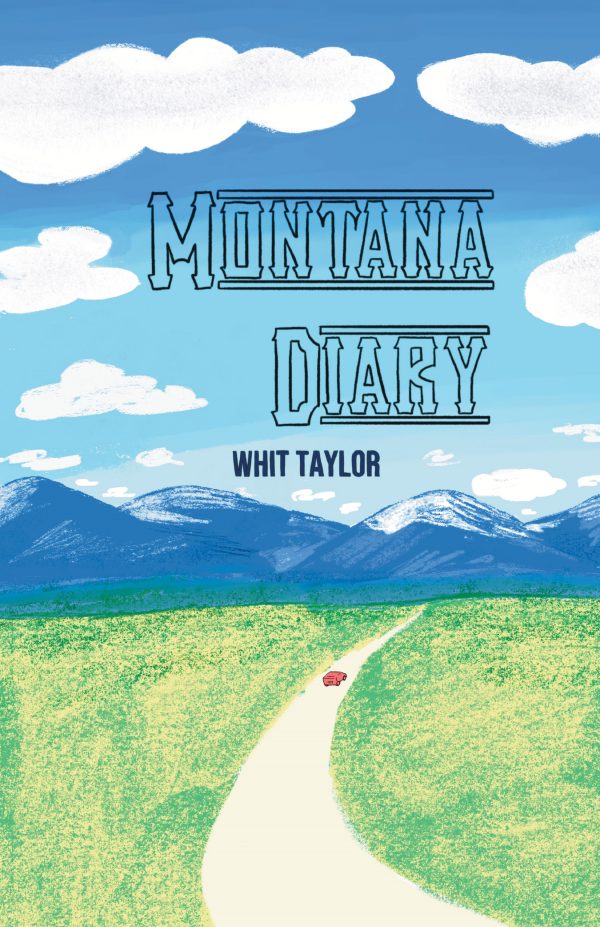

Taylor’s no-frills line drawings work really well throughout Montana Diary, utilizing almost no shading or black spaces whatsoever. Her abundant use of airy white space evokes the lore of the state’s fabled Big Sky, with the absence of border panels capturing the sense of the open possibilities of any road trip. And Taylor shows off her coloring chops in a few lovely back-page landscape drawings. The production values Silver Sprocket bestowed upon this comic are well worth it.

As their travel adventure concludes, Taylor reminds herself that “beauty can exist alongside ugliness.” That heavy knowledge permeates every scene of Montana Diary. This thirty-two-page zine boasts a rich tapestry of content, more in fact, than many full-length graphic novels I’ve read of late. It’s an entertaining, genuinely rewarding read, created with equal parts heart and mind.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply