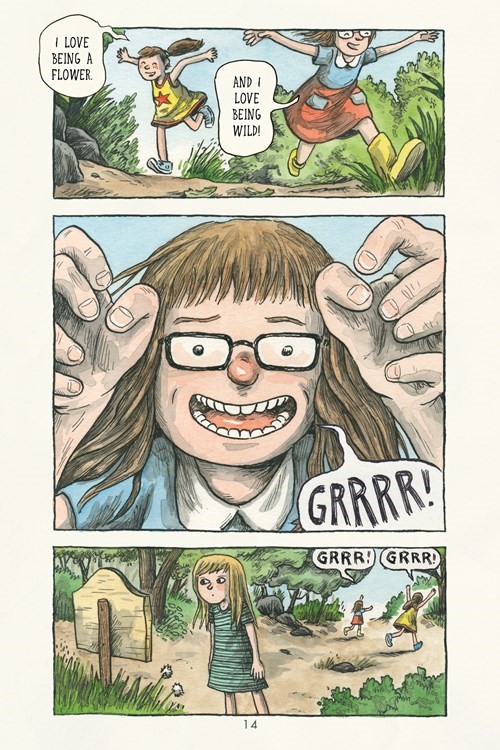

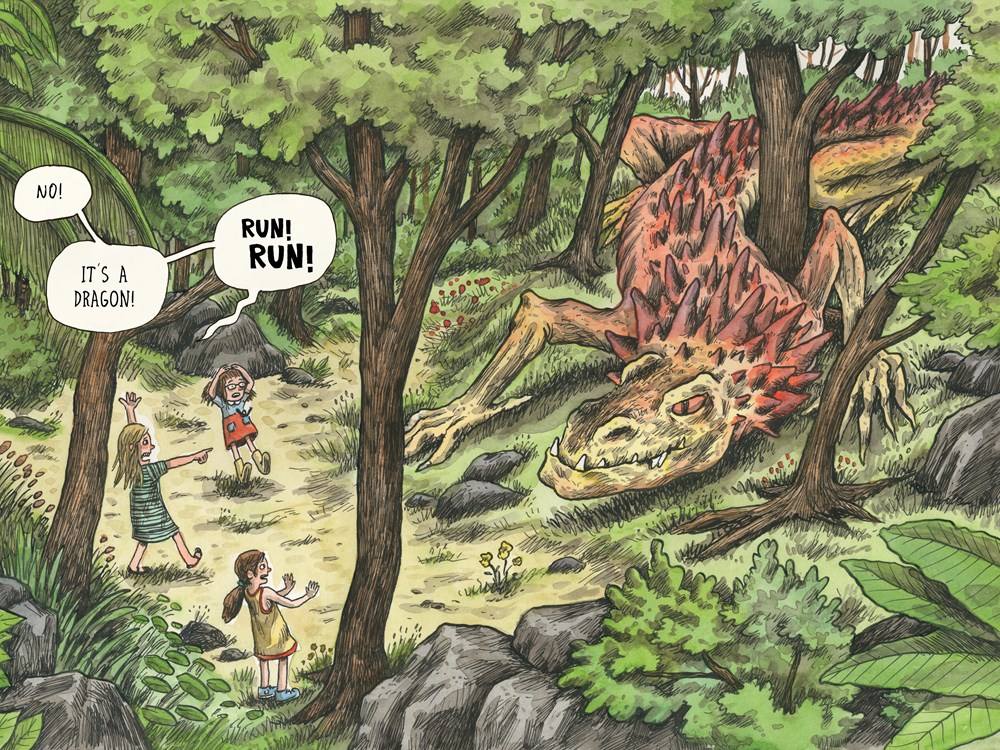

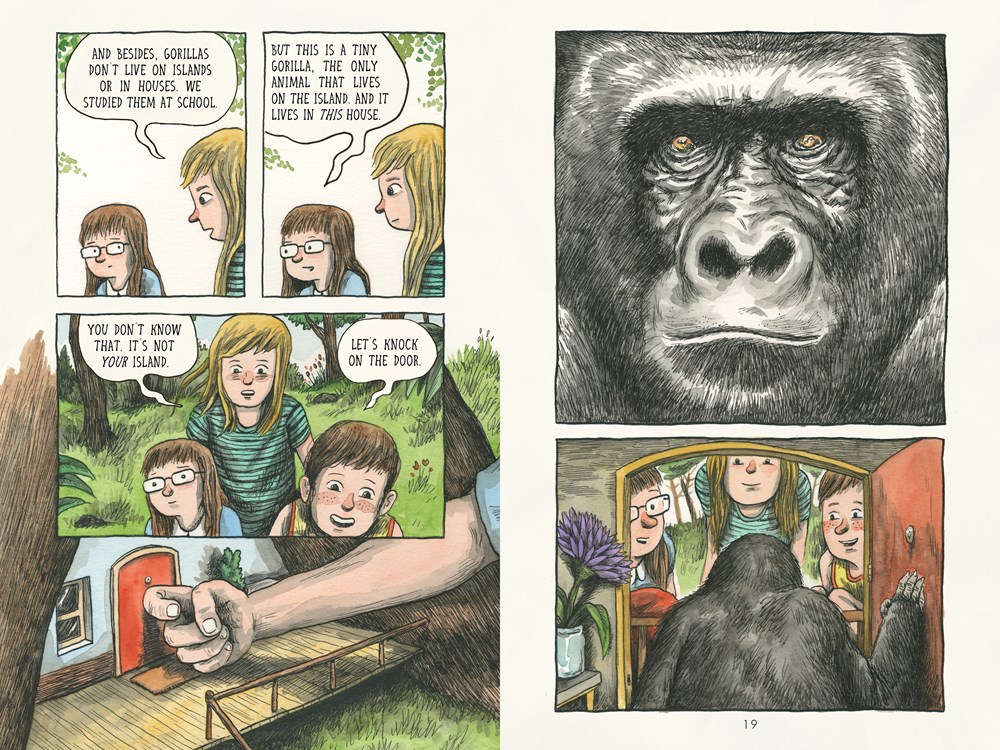

Wildflowers, the fourth TOON book by Argentine cartoonist Liniers, depicts three sisters wandering an unknown island after a fearful plane crash. However, we readers do not see the actual crash, nor any dramatic rescue. We don’t get to know much about the island, either, beyond the fact that it’s a grand setting for adventure. What we do get is a depiction of three girls blithely trekking through a “jungle” (which looks more and more like a northern hardwood forest the deeper they go) and discovering things along the way. Sometimes the sisters argue about the logic or likelihood of what they experience. The littlest can’t read and seems not to have been to “school” yet, whereas the oldest insists upon the things she has learned there. Exactly what is happening to the three of them, and how to explain it, appear to be up for grabs.

Certain details in Wildflowers threw me at first; for one thing, the girls’ affect doesn’t match the trauma of surviving a crash or being stranded in an unknown place. But this is not a story about trauma. Rather, it’s about imagination, suspension of disbelief, and play. Essentially, Wildflowers offers an adult appreciation of children’s imaginative freedom and capacity for collaborative make-believe. It seems to have arisen from adult eavesdropping into children’s improvised, interactive storytelling, complete with small moments of disagreement and friction. Of course, there are scary bits—the idea of the crash, encounters with a fearsome beast, passing uncertainties—but that’s just what I would expect from sisters or brothers riffing together, making up a thrilling, crazy story as they go.

Wildflowers takes me back to some of my earliest memories of play. When I was small—what, five or six? But then again, seven, eight, and nine?—my brother Scott dreamed up elaborately rigged scenarios for us to follow: offhandedly brilliant plots that shaped our improvisations. Whether in our own yard, at a playground, or hiking through woods on some camping trip, Scott had springboards for stories, almost like virtual film treatments, that inspired us: the adventures of spies, superheroes, or brave soldiers in postapocalyptic worlds (he was probably already at the point of writing such tales down, too). When I was very small, around six maybe, we imagined (I’m sure this was his idea) that cars driving through our neighborhood, after dark, were bug-eyed monsters whose headlight beams, eye beams, could turn us to stone. We called them, literally, BEMs, and dove behind bushes or pillars to escape the deadly sweep of their eyes. Nothing in Wildflowers is quite as awful as that, but the feeling of siblings at play is familiar, unmistakable.

Globally, Liniers (Ricardo Liniers Siri) may be best known for his surreal, freewheeling newspaper strip Macanudo, begun in La Nación back in 2002 and distributed in English by King Features since 2018 (and sampled in four English-translated volumes from Enchanted Lion Books). Many US readers, though, may know him best for his TOON books, two of which, The Big Wet Balloon (2013) and the Eisner-winning Good Night, Planet (2017), are the first two legs in a trilogy that Wildflowers completes. Together, the three books pay tribute to his three real-life daughters. All three belong to TOON’s Level 2 (aimed at emerging readers circa ages 4 to 6) and run about 32 pages each.

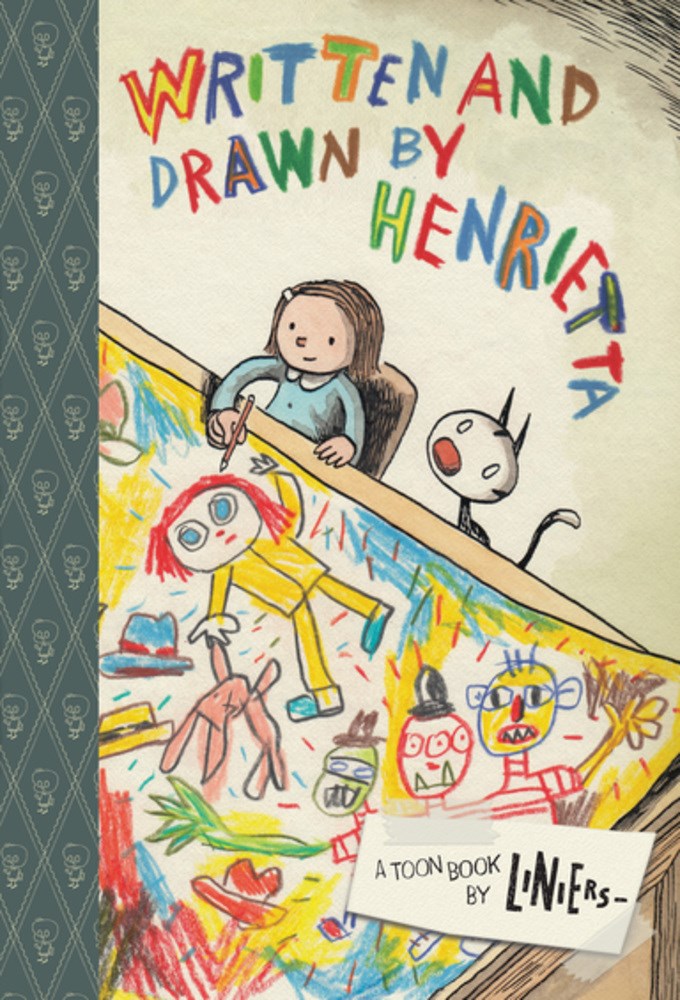

Personally, my favorite TOON book by Liniers is Written and Drawn by Henrietta (2015), which is twice as long and labeled as Level 3 (think ages 6 to 8). Henrietta is a meta-book in which what is supposed to be the work of a young girl, armed with a set of colored pencils, takes over, muscling out Liniers’s own drawing style. Henrietta (a character imported from Macanudo) writes and draws the story of a young girl’s bedtime adventure with a three-headed monster. It’s a trip. I like the book’s celebration of child-as-artist (imagine a scruffier version of Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon or Aaron Becker’s Journey) as well as the wild complications that its greater length makes possible. As a paean to a child’s ping-ponging imagination, Henrietta serves as the giddy flipside to Liniers’s darker, non-TOON picture book, What There Is Before There Is Anything There: A Scary Story (2006, trans. 2014), in which a child’s imaginings become a source of fear, making bedtime an anxious ritual. This theme of imagination, of course, recurs in Wildflowers, but in a new form and with a reassuring sisterly vibe echoing that of The Big Wet Balloon.

I note that there are no adults in any of Liniers’s TOON books. There are kids, and animals and toys, and occasionally monsters, but no grownups to solve problems or frame lessons. What lessons there are come subtly and are never punitive or even cautionary. The books take a more child-centered, as opposed to adult-centered, approach to facing down fears and solving problems. I like that.

Wildflowers, in its title and design, suggests a tug of war, or dance, between wildness and cultivation. Its two- and three-tier panel grids sometimes give way to multilayered pages that float panels “on top” of unpaneled bleeds: absorbing evocations of space and context. That is, Liniers tends to disrupt his traditional paneling with backdrops that conjure a wild and immersive environment. As if to match, his cartooning, gorgeously rendered in ink and watercolor, boasts a lush greenness, a luxuriant, overflowing richness. Yet the book’s overall aesthetic remains subtle and contained. The three sisters are indeed wild, but also beautiful and delicate, a connection which reminds me that kindergarten, after all, means “children’s garden”—a metaphor for schooling that balances the notion of children’s spontaneous growth against the hope that responsible gardeners (teachers) can cultivate the young. If likening children to blooming flowers is an age-old trope, Liniers plays into both sides of it, the untamed versus the fragile, the ever-lively versus the carefully tended. The result is, depending on your viewpoint, either a fittingly rowdy (but not too rowdy) celebration of children’s imaginative freedom or an oddly decorous sort of adventure: wildness within safe bounds. (This is one of many ways that the book echoes Maurice Sendak’s inescapable Where the Wild Things Are.)

Designed by Liniers and TOON Editorial Director Françoise Mouly, Wildflowers is a small gem of a children’s hardcover book—a sweet end to Liniers’s fatherly trilogy. I have to confess that it doesn’t quite tickle me the way that Written and Drawn by Henrietta does; I’d like it to be a bit less anxious to reassure, a bit, um, wilder. But it is so well-observed, so in tune with the three sisters and the differences among them, that I can’t complain. And, as in The Big Wet Balloon, the idealization of sisterhood comes complete with little tensions and complications. Liniers knows these girls, and he knows how to balance cuteness against trouble. What he has done with TOON so far—well, it’s one of the lovelier runs in today’s children’s comics.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply