Sophie Yanow draws great legs. There are artists who are masters of the face, who are able to show everything a character thinks and feels with a glare. Then there are cartoonists who can tell a story through body language, drawing characters with their arms flailing wildly or their shoulders raised in indifference. Rarely have I seen someone like Sophie Yanow, though, who can tell you everything you ever wanted to know about a person through the movement of their legs alone.

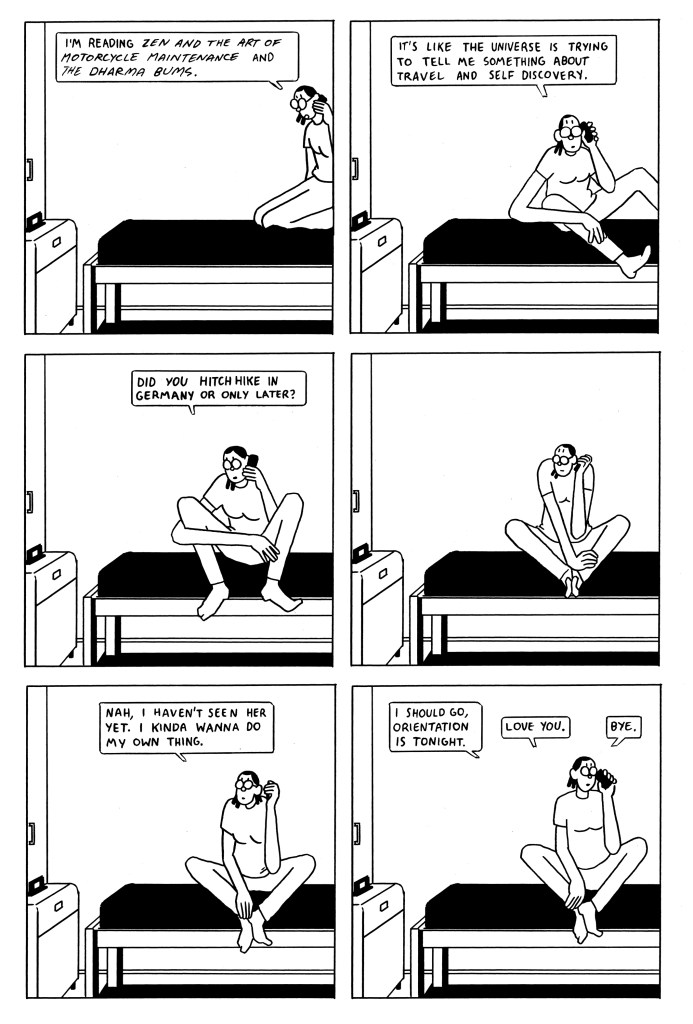

For example, an early scene in her semi-autobiographical graphic novel The Contradictions shows Sophie sitting on her bed as she is talking on the phone. At first, the figure is sitting upright on her own knees, but, as the conversation progresses, she changes position and begins to shift uncomfortably. Her legs grow ever closer to her body, forming something like a shield around her. The reader doesn’t need the words in the speech bubbles – Yanow makes it obvious how anxious the character is feeling just from the changing position of her limbs.

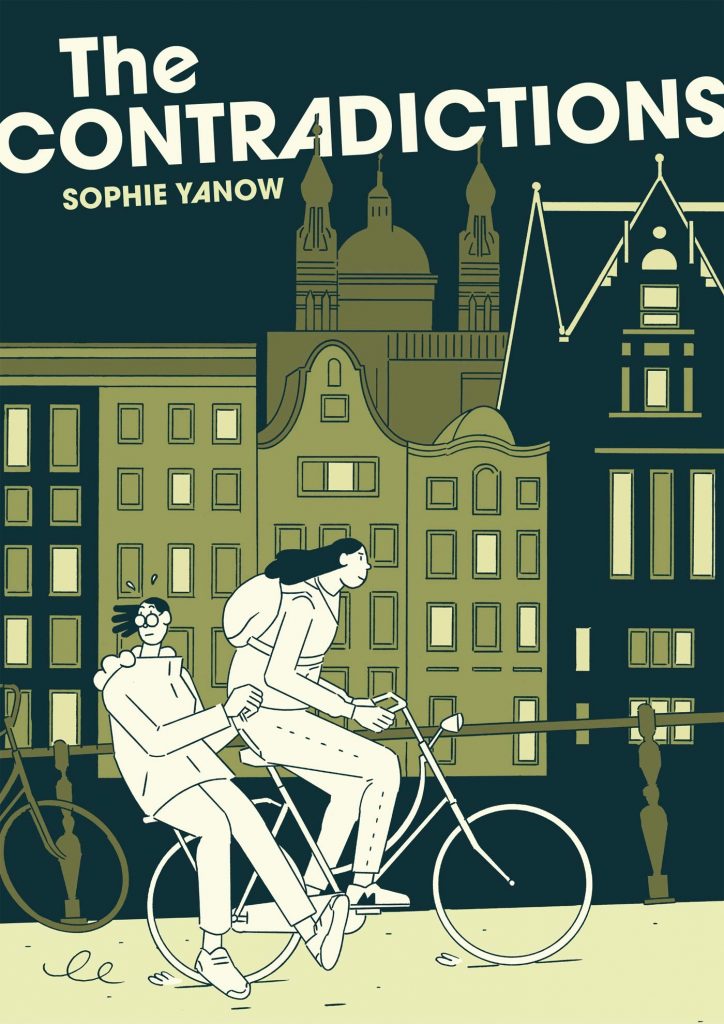

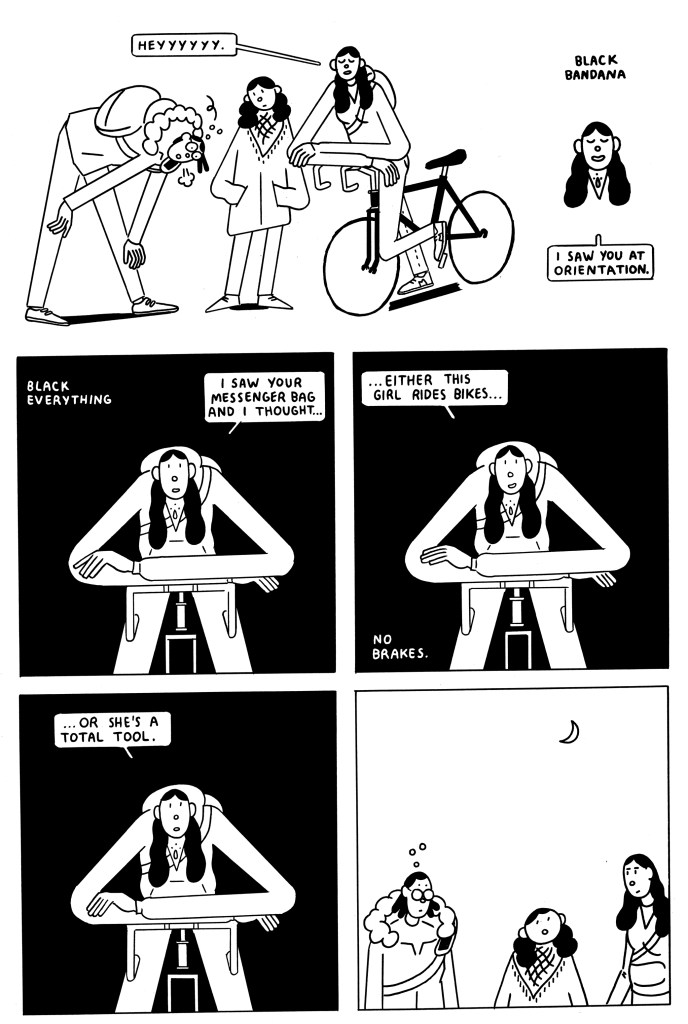

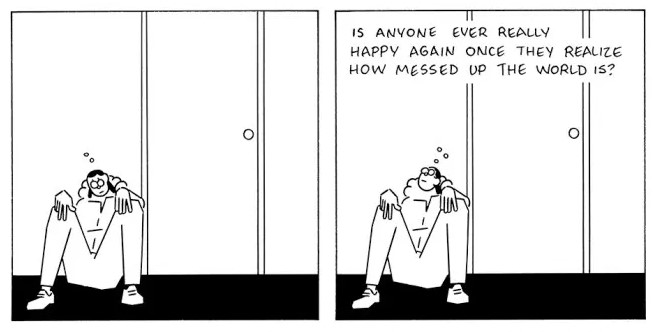

Yanow’s artistic style, in which simple figures are defined by long spindly appendages, is in full force throughout The Contradictions. This is, after all, a story about movement and distance — not just the distance the characters cover on foot, but emotional distance as well. These are young people constantly testing the boundaries of their relations, never quite sure where they stand with one another, how deep their connection is. The way Yanow draws her characters is likewise useful in showing the relative inexperience of these characters. These figures appear as if they might bend and twist with every motion, which is probably the best encapsulation of the young student’s experience as their every step is fraught with terror because the world is an unfamiliar minefield.

Lonely and mostly confused while studying abroad in Paris, Sophie finds herself attached to Zena, another American student in The Contradictions. Zena immediately catches Sophie’s attention with her self-assured ways. Zena fills Yanow’s head with radical ideas: anarchism, commune living, hitchhiking. Guided by Zena’s strong personality, the two decide to combine all three ideas and break away from the routine of their life by hitchhiking through the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany, trying to discover, on the road, the idealism they fail to find in their school books.

Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road appears to be a chief inspiration for The Contradictions, with Zena playing the role of the charismatic and carefree Dean Moriarty; The Dharma Bums, a different Kerouac novel, is actually referenced within the comic. Much like the relationship between Neal Cassidy and Kerouac, Zena doesn’t necessarily try to influence Yanow to be like her, but the lost protagonist starts to model herself after her more compelling travel-mate anyhow. Sophie tries to become a vegan, at least for the duration of the road trip. She ends up constantly giving in whenever Zena becomes more aggressive in her demands. This leads to the ironic note felt throughout the trip: in trying to find freedom, Yanow ends up finding just another system of rules, even if the one cardinal rule is “follow Zena.”

There’s never a boiling point to The Contradictions. Zena and Sophie constantly almost get on each other’s nerves as they realize they don’t necessarily want the same things Whenever things appear as if they might explode, Sophie ends up backing down. It’s the sort of story that might appear one-sided in its depiction, Zena easily could appear as a relentless bully, but Yanow is smarter (and too emphatic) to fall into that trap. Zena is not being difficult, she’s just being different. A large part of the journey in The Contradictions is about Sophie recognizing that she doesn’t have to re-model herself in order to appeal to others.

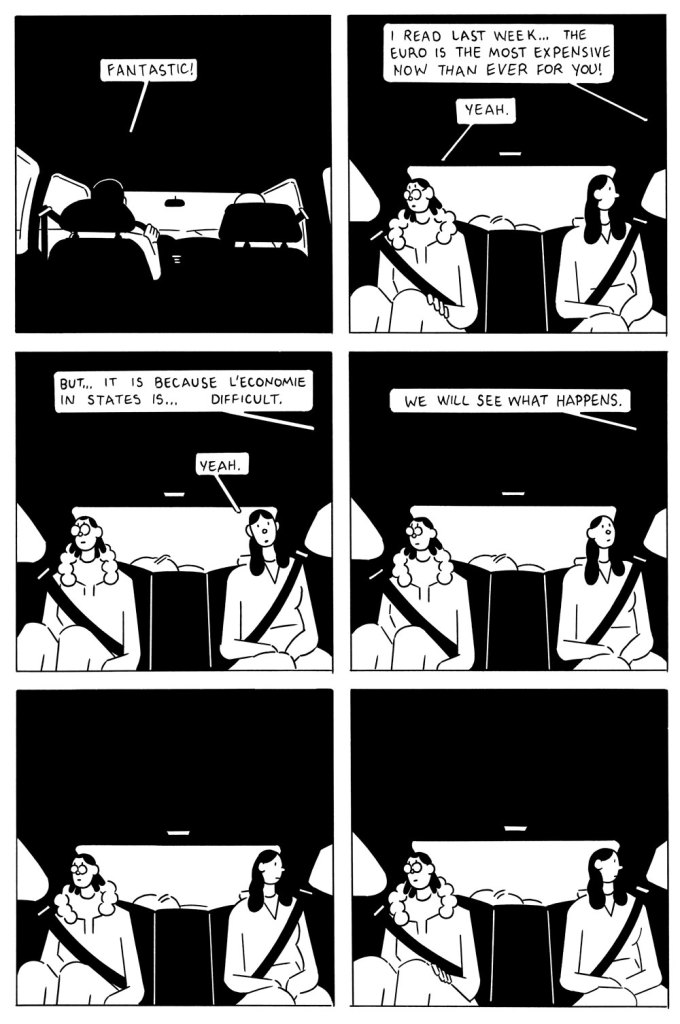

Like many a Bildungsroman, the physical movement of the story is mostly there as an anchor for the psychological development the characters go through. While I have mentioned Yanow’s skills with body language, she also has great ability in other areas of cartooning. Look at the page showing the two protagonists in the back of a car, note how finely observed their facial expressions are. Witness the quality storytelling in the near-microscopic movements of Zena’s head or the way her features tilt slightly upwards in the fourth panel. The reader can even see, in their mind’s eye, the expressions of the driver, even though his face isn’t shown. Yanow expresses so much story out of these three different characters in the limited space of a single page. Yanow’s cartooning shines through its empathy, allowing all the characters throughout The Contradictions to feel like three-dimensional human beings. Everyone has their own story to tell. The people the protagonists meet on the road, even the bit players, always feel like actual people. Yanow gives them a manner of essential dignity.

Yanow’s style has metamorphosed since her early days, losing some of the rougher edges that characterized works like The War of Streets and Houses and What is a Glacier? Her figure-line, in particular, is more pleasing in its softness, and more easily finds the humanity of the characters in the minutia of everyday life. She does this while still maintaining her strong grasp of physical spaces and urban development. Her backgrounds are often sparse, but that does not detract from the strength of the artwork in depicting location; Yanow simply knows when to let the figures stand on their own and when to showcase larger sections of the cities they visit. I wouldn’t call her choices in The Contradictions “evolution,” because that implies that the art here is inherently better than Yanow’s older work. What we have here is mostly a slight shift in the artistic direction. It shows Yanow can still find new means of expression within her established style.

Every journey reaches its end, and I think the end might be the point in which some readers depart from the book. I find myself of two minds about the conclusion of The Contradictions. It is a masterful depiction, but of something I don’t necessarily want to see: someone having a taste of the ‘radical life’ only to turn back at the last moment. It’s anti-climactic in a way that is both expected and logical and is another sign of how engaged I was with the story, with these people and their life, that I ended up almost distressed by such a simple choice.

Sophie Yanow might not give us everything we want, but she gives us a bit of her life, and she does it in such a skillful way that one cannot help but be enamored with it. The Contradictions isn’t a guide for how to live a radical life, nor is it trying to be, it’s a depiction of one person’s journey. What the readers end up taking from that journey is up to them. Closing the book I realized that, like Yanow, there are periods in my life in which I am still looking for guidance. In the end, though, no one can make your choices for you, not one person can provide all the answers. You have to choose your own path.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply