Just shy of fifty years after his passing, Otto Binder has suffered the fate of most of his peers in the American comics industry: a man subsumed by the characters he created and wrote, his influence ever-present (albeit, at this point, more infrastructurally than overtly) but his name all but forgotten by the current-day reader. Binder’s subsumption of the ever-hungry comic industry was more literal than others: in recent years the man’s name has arguably been invoked more frequently in the context not of his real-life work but of his stand-in character in the recent DC comic Rorschach, in which Binder’s real-life trauma, the car accident that killed his daughter Mary and sent him down a depressive spiral that he would never recover from, has been transformed into some manner of retcon-pornography involving Doctor Manhattan (let the record show that I do not recommend looking this up). But he was an extraordinarily prolific writer, in both comics and prose, leaving behind thousands of known writings – and at least one unknown one.

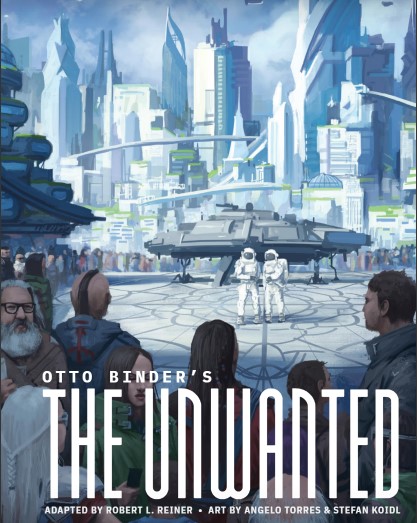

The Unwanted has all the makings of a great story-about-stories: ever compelled by the politically didactic, in 1953 Binder (under the pen name Eando Binder, typically shared with his brother and occasional collaborator Earl, though this story is framed as one Binder wrote solo) wrote a short prose story—but did not publish it, for some unknown reason. Perhaps afraid of the repercussions of writing a story that vocally and ardently opposes the overwhelming bigotry that defines his home country, Binder kept The Unwanted well away from view, sending it only to the most unlikely reader: a thirteen-year-old fan, Robert L. Reiner (not the Rob Reiner you’re thinking of), who wrote fan mail to Binder. For years Reiner held onto the manuscript of this story, assuming that Binder, prolific as he was, couldn’t have let this one simply die in silence; it was only years later that he learned that, for all intents and purposes, he was the only individual who knew of this story’s existence. It is this very story that, seventy years after its writing, has now been published in a handsome little hardcover edition by Fantagraphics Underground, with illustrations by Angelo Torres and Stefan Koidl.

Sort of.

What the publication appears to want its readers to overlook is a key two-word phrase: “Adapted by.” Indeed, Reiner in this case becomes more than the owner of the physical manuscript, but also the adapter of this particular edition. The nature of this adaptation is unclear, and it is only the backmatter that hints at its scope: an interstitial page preceding Reiner’s afterword shows one typewritten passage, the opening passage of Binder’s original draft, revealing that, while the contents of the story (or at least its start) are identical on a beat-to-beat basis, the language was at least partially rewritten and rephrased, calling into question the very nature of its authorship, and of the title’s attribution to Otto Binder.

Judging by the two snippets that allow for direct comparison, Binder’s prose is in itself clunky and stiff, seemingly hesitant about the urgent messages it wishes to convey and the vessels that contain them; yet Reiner’s prose is even less elegant, leading one to wonder why any change was needed in the first place. Of course, because all I have of Binder’s version is the very opening, it is hard to gauge the scope of the change. But whoever wrote (or rewrote) the story, simply put, failed to account for, or evidently desire, any potential impact. The prose is more clinical than evocative, reporting its messaging crudely, almost reluctantly.

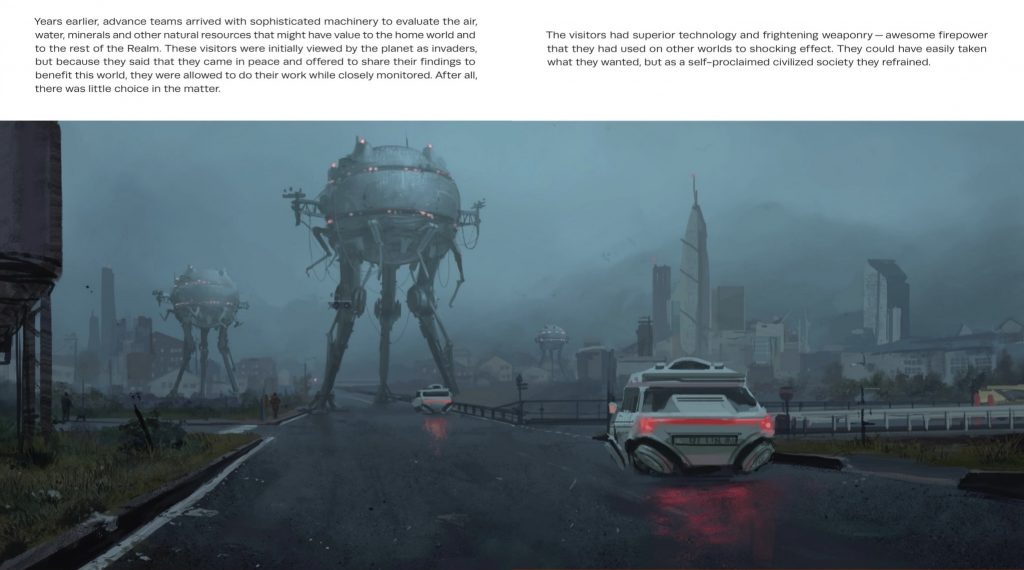

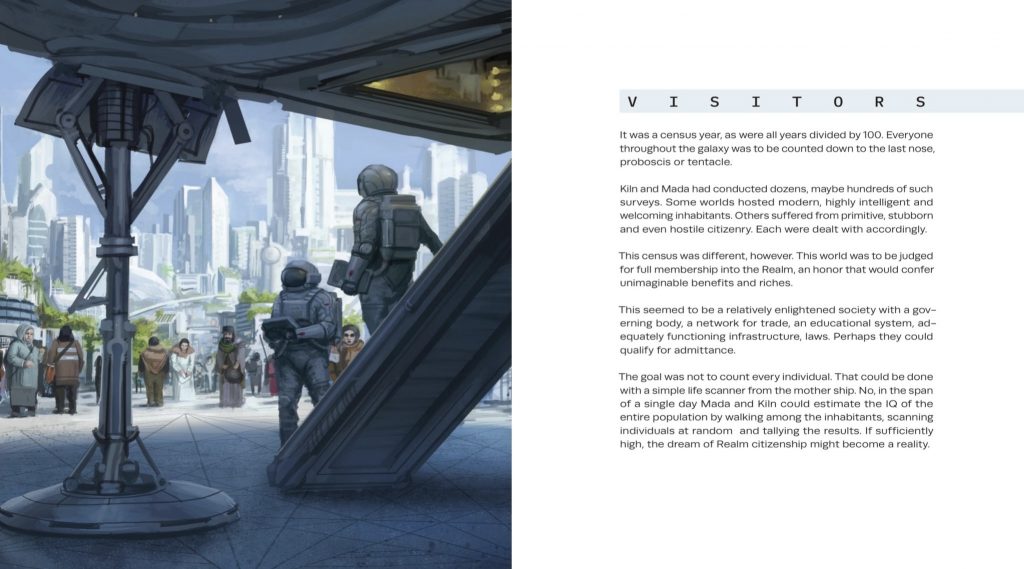

Telling the story of a galactic empire that only treats planets as worthwhile so long as it serves its political and economic interests, The Unwanted makes Binder’s EC Comics connection clear, right down to the twist: that the galactic empire’s measurement devices, this ultimate meter that serves as the be-all and end-all of value, measures alien civilization’s IQ—standing not for intelligence quotient, but for intolerance quotient. In case you didn’t get that intolerance is bad, the story ends thusly:

“Mada removed his helmet. And in the glow of the bright yellow sunlight, exposed in all its glory and significance, the secret of their proclaimed supremacy: the color of their skin.”

It’s hard not to think of EC Comics such as Judgment Day by Al Feldstein and Joe Orlando, whose aesthetic sheen barely tried to hide its critiques, and I’m fine with that; I don’t necessarily mind didactic narratives, and I am even willing to admit that I am much more forgiving when the didactics align with my own politics. But what I, as a reader, must question is the thinness of the prism: the strength of allegory requires some degree of refraction, some manner of artful distancing between the signifier and what it signifies. Alternating between expository statements on the political mechanisms of its world and the shabby core plot of two surveyors arriving at an insufficiently-intolerant world, The Unwanted feels completely at ease with its artlessness; its stand-ins are only barely stand-ins, and its approach to storytelling seems to care so little about story that it renders its allegory futile.

It’s a crude approach that may have been poignant when the story was written—indeed, not denying the significance of a white author condemning white supremacy in America in 1953—but the fact that this book desperately wants its readers to remember is that it is not 1953 anymore and that this is not the story that Otto Binder wrote alone. Emil Ferris, in her foreword, claims that “[a]t this pivotal moment in the history of humanity when the drums of war are being beaten all over the world it is no mistake that Otto Binder’s lost story is published,” positing in no uncertain terms that this is some sort of defining political text for our times.

It makes me wonder, in part, who the audience for this book is supposed to be; I do not usually take evident target audience into critical consideration, but it would appear that this book wants to be read by someone who opposes white supremacism and yet needs “white supremacism is a problem” to be the end of the discussion and the whole of the condemnation. It appears to take comfort in the political as an aesthetic to be partaken in, in a praxis embodied by the obvious. It is telling, in this regard, that Ferris ends her introduction by saying that “[m]aybe it will be the magic of stories that will save us in the end,” and her foreword by saying that, “[w]hen finally we know our collective power as story tellers and story hearers and story manifesters (magicians, all), I believe that we will collectively write the final chapter of Otto Binder’s lost story“: this is a publication drowned in the perceived importance of performance and its conflation with action.

The art by Angelo Torres and Stefan Koidl is a contributing factor to the overall perplexing nature of this book’s very existence. From Reiner’s afterword, it is clear that Torres, aged 86 at the time Reiner first approached him for this project, did not feel up to the task of drawing the whole project by himself. What perplexes me, though, is the choice of a painter who does not appear to have anything to do, aesthetically, with the task at hand: Torres, being an EC Comics artist and a collaborator of Binder’s, feels like a natural choice, one that brings with it a distinct, unambiguous aesthetic tone, and so choosing a semi-naturalistic painter for an attempt at sci-fi photorealism to “bring Torres’ art to life” feels dismissive of the point the book purports to celebrate. The art, too, is guilty of telegraphing its own allegorical shortcomings, as the world visited by the two protagonists shares the aesthetic of the self-devouring “far-future Earth” aesthetic that visual pop culture has invariably bombarded us with for the better part of a century, with an overly-smooth, slightly-smeared texture that bears none of the weight that defines Torres’ work.

Otto Binder’s The Unwanted had all the makings of a great story-about-stories, a wonderful little archival curio, but, instead, it was hindered by the need (and failure) to demonstrate its own significance. Guilty of an overwhelming tendency to obviate itself, it is a supposed celebration of a political faith that it is not quite willing to pursue, of an art that it is not quite willing to show an active interest in, and of an author whom it does not respect enough to allow his work to stand up on its own without interference.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply