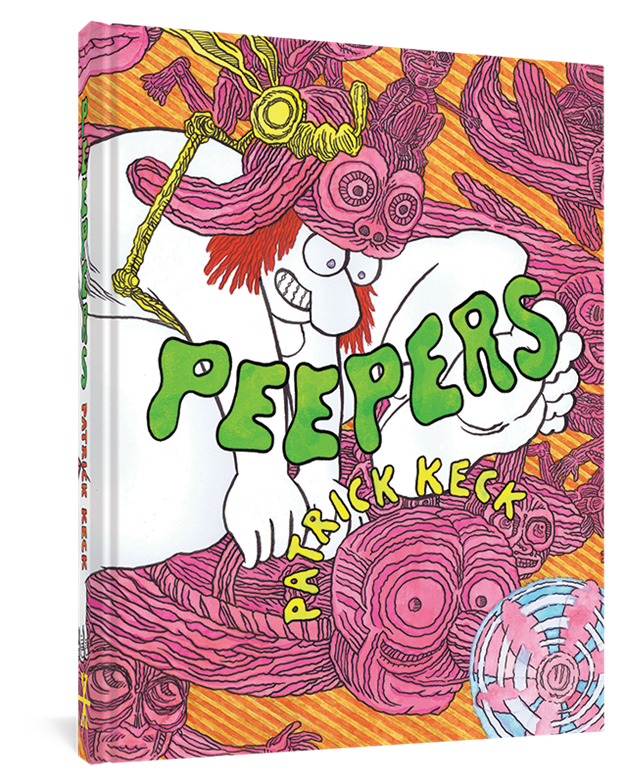

Projects with long and complex gestation and creation periods have always been fascinating to me, but in the case of Patrick Keck’s Peepers, it might be fair to say they were only long. By the artist’s own recollection, the ideas that coalesced into the story first came to him around 2008, and he duly began scribbling words and images into various Mead notebooks, but he started writing and drawing the strip “proper” around 2010, at which point early installments were posted onto the Study Group Comics website on a fairly regular basis — for a while, at any rate. Keck moved onto other things, both as a “solo act” and in collaboration with others, but he kept coming back to this comic here and there, off and on, now and then, as time allowed for and interest compelled, right up until very nearly the present day and its final, complete release in hardback from Fantagraphics Underground just last month. So, yeah, over a decade? That’s a long time.

But its evolution from idea to book doesn’t, weird as this might sound, strike me as being terribly complex — Keck just worked on it when he both felt like and, crucially, could. It just so happens that those instances where he was able to and/or chose to devote himself to it were interrupted by either other projects or simply life itself and who, I ask you, can’t relate to that? What will probably surprise no one, however, is that a work this long in the making looks and feels quite different at the end than it does at the beginning.

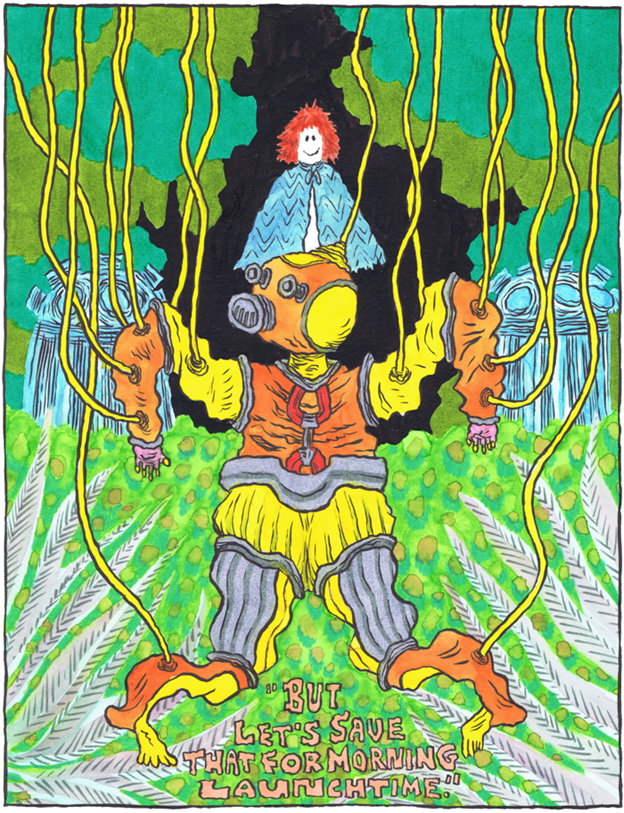

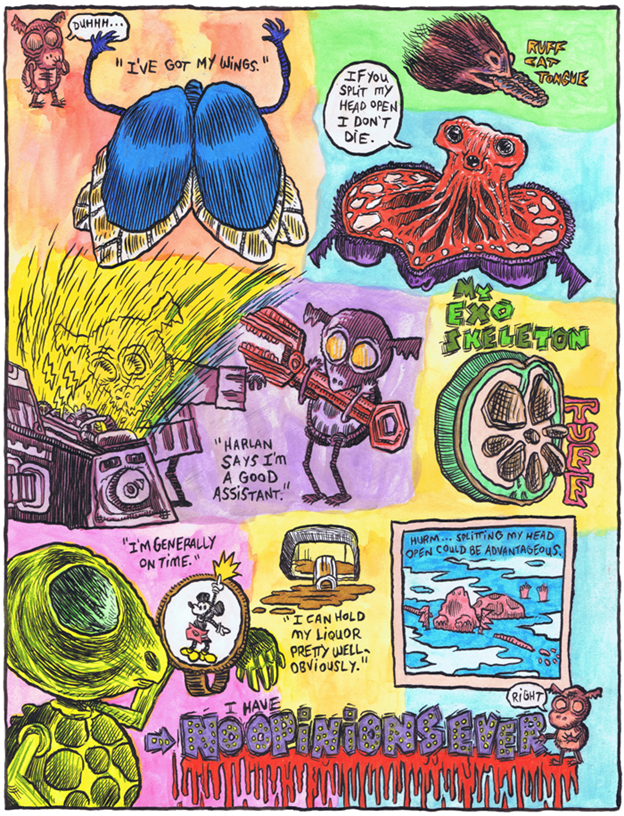

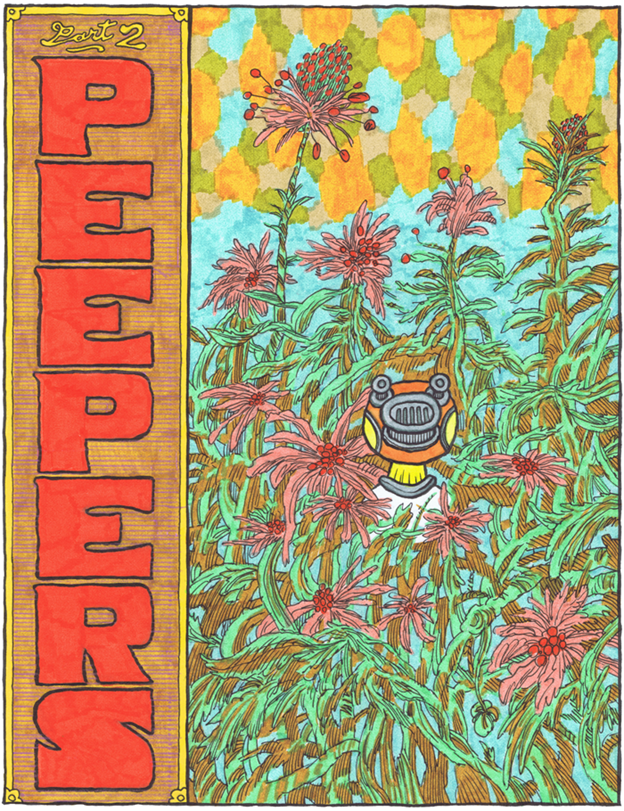

Please do not, however, take that to be a bad thing. In fact, one of the most fascinating things about this book is charting its own evolution not just stylistically but thematically and tonally. Keck’s cartooning certainly becomes more solid, more self-assured, and more clear in its purpose as events progress, but that’s only scratching the surface. It seems to me that his intentions for the work shifted and evolved over time, as well. The dark and foreboding and barely post-traumatic mindset of our protagonist, Peepers, and the desperately lurid intentions of her erstwhile alien companion, Jeffrey, are tinged with a kind of inevitable doom at the outset that plays against the energetic, hallucinatory linework and vibrant colors of Keck’s bio-organic landscapes and mindscapes. As things move along, though, art and story both begin to coalesce, first establishing and then reflecting, a unified verbal and visual “voice” that is every bit as mysterious as it was in the early going but decidedly less ominous and predatory. There’s still plenty in this extended quest narrative that will leave you feeling queasy, make no mistake, but as Keck’s authorial point of view slowly transitions from dispassionate observer to sympathetic caretaker of his own creations, what could be horrifying instead mutates — maybe even matures — into a series of events that are instead revelatory.

In fairness, if the medium is the message, then the message here is a mixed one indeed, as Keck deploys everything from acrylics to colored pencils to watercolors to standard pencils and inks in service of creating a world — or perhaps a dimension would be more appropriate — that is never anything less than a cornucopia of wonders for one’s optic nerves to process, but that intuitive methodology more or less always works to the book’s benefit. Yes, there are whole pages, even sequences of pages, that look as though they come from an entirely different comic, but they don’t serve to jar the reader so much as to expand the scope of the story’s possibilities, which are open-ended bordering on limitless in the first place. Push yourself to the limits of your imagination and then keep pushing is Keck’s matra in theory and practice, and the result is a work that refuses to be pigeonholed by simple dint of the fact that it can’t be. This may result in some unevenness, no question, but it’s conceptually and artistically exciting unevenness, and that’s something I never complain about.

One thing you may have noticed, however, is that I’m assiduously avoiding detailed discussion of the plot, and you may rest assured that’s not by accident. The unvarnished truth is that this is a fairly straightforward journey from one place to another, but that kind of brutally reductive description does the book a tremendous disservice. Like any undertaking worth its salt, this is every bit as much about where Peepers goes within herself as without, and the very act of becoming itself takes precedence over what it is she ultimately becomes. Much of what we are witness to in this story is unpleasant, much of it is entirely interpretative, and most all of it is what I would describe in a pinch as “biological psychedia,” but I hope I’m not giving too much away when I say that when we get inside our protagonist’s head, we really do get inside her head. I’m not necessarily prepared to say that the ultimate outcome is a happy one, but such value judgments as happy/sad or even good/evil are so far in the rearview by the end of the book’s first of five (plus epilogue) chapters that you’d have to be a square to still insist on measuring the resolution by them when it finally arrives some 200 pages on. What I will say, though, is that it’s appropriate to the journey we’ve just been on. It works and it’s ambiguous and it’s definitive in equal measure.

Of course, that’s contradictory, but contradictions are baked into the cake here along with everything else. Peepers, you see, is more than just a comic per se, it’s a documented record of its own creator’s years-long and ever-evolving approach to both conceptualizing and creating it, as well as a de facto examination of his own attitudes toward both it and the purposes behind it. As such, while I have little doubt that there will be more accomplished, more cogent, and certainly better-realized comics to come our way as 2021 unfolds (the year is young, after all), it wouldn’t surprise me in the least if there are none that prove to be as inherently interesting as this one is.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply