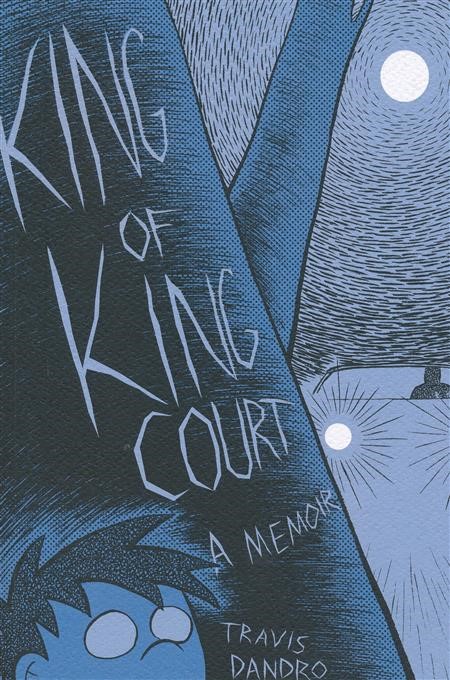

There are any number of “child’s eye view” memoirs competing for the attention of the contemporary comics reader, but Travis Dandro’s 2019 debut graphic novel, King Of King Court, makes the most of that particular visual and narrative storytelling “hook,” even if the results are admittedly a mixed bag. How much of that is by design and how much is down to uneven execution is something of an open question — to my mind there are pretty clear instances of both — but making that on-the-fly judgment call is part of the fun of this book, although given its harrowing subject matter I should state for the record that I use the word “fun” advisedly in this instance.

So, yeah, about that “harrowing subject matter” — Dandro’s memoir starts with his six-year-old-self learning that his best grown-up buddy, Dave, is actually his father, and things only get more convoluted in his life from there. Growing up in the “white trash” Massachusetts exurbs is probably no easy task at the best of times, but no one would equate young Travis’ upbringing with the word “best” in any way, shape, or form. Dave attempts to play a more active role in his son’s life at the same time that his own issues with drug addiction begin to get the best of him, and his resultant legal troubles cause plenty of stress for himself, his well-to-do family, and Travis’ already-overwhelmed mother, who’s married to an alcoholic, abusive loser. You could be forgiven for shouting “Jerr-y! Jerr-y!” at this point, but there’s nothing comical or freak show-like about this from Travis’ still-developing point of view, and as he grows and matures (the book follows him all the way up to his teenage years), the narrative tone becomes more clear and grounded, if less wonderfully (again, a term I employ with all due caution) perplexing.

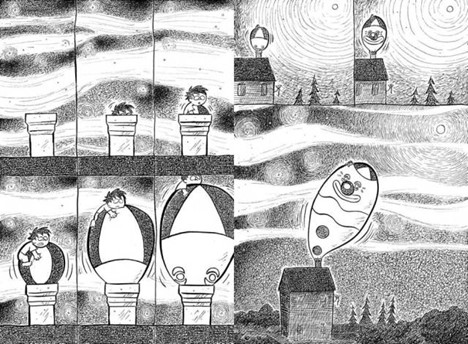

To give credit to Dandro — and his publisher, Drawn+Quarterly, who seem to have taken a noble “hands-off” stance to much of this book in an editorial sense — there are some very strong sequences in the early-childhood portions of this book. Notably, sequences in which dreams and consensus reality are still battling it out for prominence in the future artist’s developing mind and objects take on significance well beyond any their actuality would logically dictate — emotional interpretation being, in his more tender years, visually privileged over the hard-and-fast “facts” of his life. He struggles a bit with the transitions “from” the real world “to” his dreams and imaginings and back again, yes, but he comes as close as any cartoonist this side of the great Sarah Romano Diehl in terms of portraying the actual character and nature of how memory works in the early going here, only to see some of that naturally enough wither slowly away as the curse of understanding takes hold in his maturing consciousness. That’s not the fault of Dandro himself, of course — you can blame the simple act of growing up for that — but it means that as events progress, his method of communicating them visually becomes less ambitious and more cut-and-dried. Such is life.

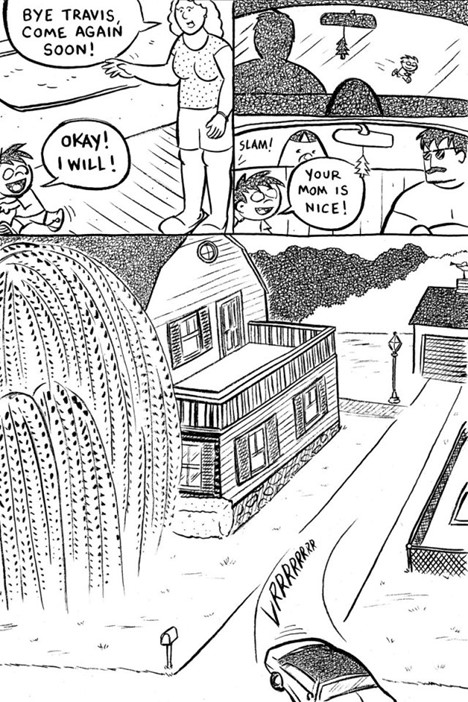

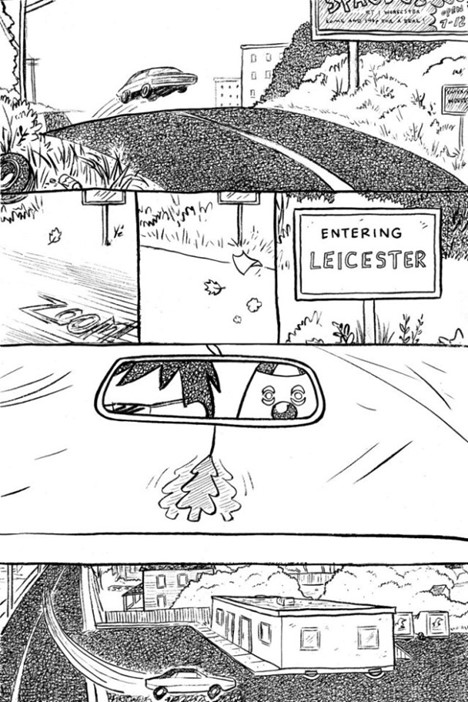

Certainly, Dandro’s skills as a pure illustrator are never in doubt. His juxtaposition of classically-exaggerated “cartoony” figures and faces with painstakingly-rendered backgrounds and atmospherics (his cross-hatching, in particular, is just plain intense) is always impressive, but it loses some of its luster when tasked with adding nuance and character to, again, the book’s later pages, where they’re employed in service of communicating things that are logically understood rather than subconsciously interpreted. One thing that remains consistent throughout, though, is his formally-innovative discarding of panel “gutters” in favor of thin, un-ruled lines which lends everything an extra degree of fluidity without resorting to the over-used trope of completely border-less panels. Still, even this takes on a feeling of increasingly concrete absolutism as the story progresses and Dandro himself ages.

And yet — this change and evolution, this subtle expression of the development of consciousness, adds another layer or meaning to the narrative. The “story” per se may revolve around family dysfunction, tumult, and, yes, abuse, but running underneath it all is something of a requiem for lost innocence made all the more poignant for the fact that Dandro grows to realize that innocence was never even really there in his case. His youthful illusions may have been uncomfortable in the extreme very frequently, but there was a comfort in the simple act of being able to have them, and, as they recede in the cold light of day that comes when one is more able to process things on an increasingly fully-conscious level, well — reality bites, and dreams are better even when they’re confusing and scary and shitty.

It’s tempting to invoke the old “ignorance is bliss” adage, but Dandro never shows himself to be truly ignorant of the contours of his existence, no matter his age — only the details. As those become more clear, King Of King Court transitions into more of a standard-issue memoir, but I give him kudos for being absolutely committed to maintaining his core conceit of conveying things as he remembers them, even if his book becomes inherently less fascinating along the way. Unless and until something really radical happens — say, a resolution between dream and conscious reality that gives very nearly equal weight to both (don’t laugh, that mindset prevailed for about 99% of human history and is more or less how most animals think) — “magic and loss” will be the way of the world, even in lives where magic is hard to come by and loss is a constant.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply