Alec Robbins’ Mr. Boop falls within the rich realm of the cartoon crossover, which has been utilized by executives and copyright holders for decades to generate hype for their properties and reap the resulting profit. Crossovers can be called into existence for other purposes as well; emerging from the War on Drugs, the 1990 McDonald’s-sponsored and Disney-produced Cartoon All-Stars to the Rescue featured beloved cartoon characters like Bugs Bunny, Garfield, and the Muppet Babies imploring the child protagonist — and the children at home — to not use drugs. The special was simulcast on all four major networks, complete with an introduction from then-president George HW Bush and First Lady Barbara Bush. Kids tuned in and were likely disappointed to find that the fantastic potential of the concept had culminated in propaganda featuring a group number about all of the “wonderful ways to say no” to drugs.

In the mid and late 2000s, on forums, blogs, and image boards, now-adult users could gather and discuss media in a new capacity. Users commonly discussed nostalgic ephemera, including the aforementioned Cartoon All-Stars to the Rescue. More broadly, cartoon crossovers were skewered on these forums because their large budget and potential still resulted in little satisfaction as a viewer. Complaints arose in various forms — canon was broken or unacknowledged, character designs failed to be properly translated between studios, and so on. With the internet, users were able to air criticisms that had perhaps not been accounted for in publications and programs with corporate sponsors.

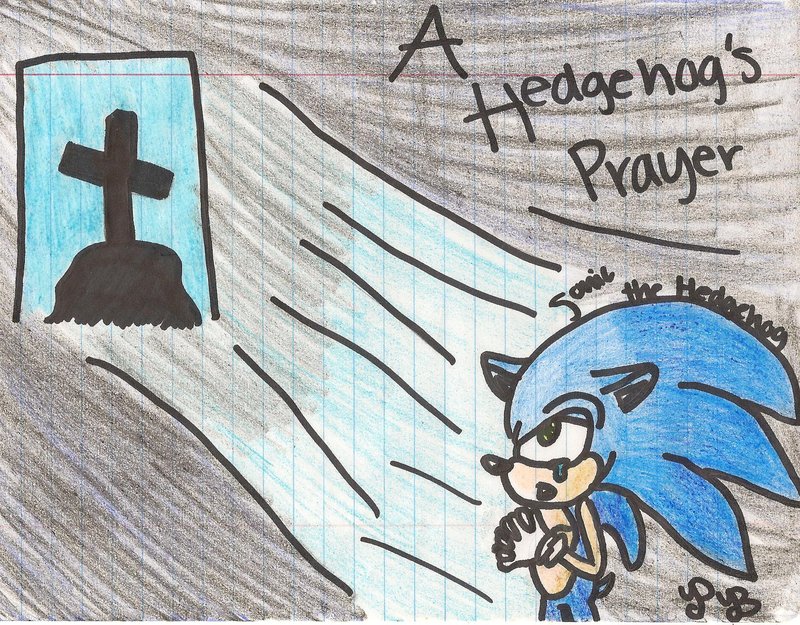

However, the internet suddenly rendered accessible the work of any artist whose images were uploaded, in contrast to heavily curated official merchandise and tie-ins, and a quick search for a well-known character would easily return thousands of works by thousands of artists, both “official” and “unofficial.” This was often the methodology of harvesting content for “cringe threads.” People dedicated themselves to gathering “cringe,” competing to see who could find the most ridiculous, most second-hand embarrassment-inducing image. These threads functioned as a sort of asynchronous B-movie club; cringe could be evoked by the art, the content, or simply the context. For example: lovingly crafted 9/11 memorial art featuring Winnie the Pooh crying over the twin towers; Sonic the Hedgehog kneeling at the cross; a sultry drawing of Gadget from Rescue Rangers, not to mention her Russian cult.

Soon works emerged from a more ambiguous place, where readers were unsure if they were genuinely made by isolated fanartists or were created with a streak of irony by those familiar with cringe. Such works include “My Immortal” and “Tails Gets Trolled.” Mr. Boop is woven from this thread, a 4-panel Instagram comic contribution to the ambiguously ironic sub-genre of the cartoon crossover.

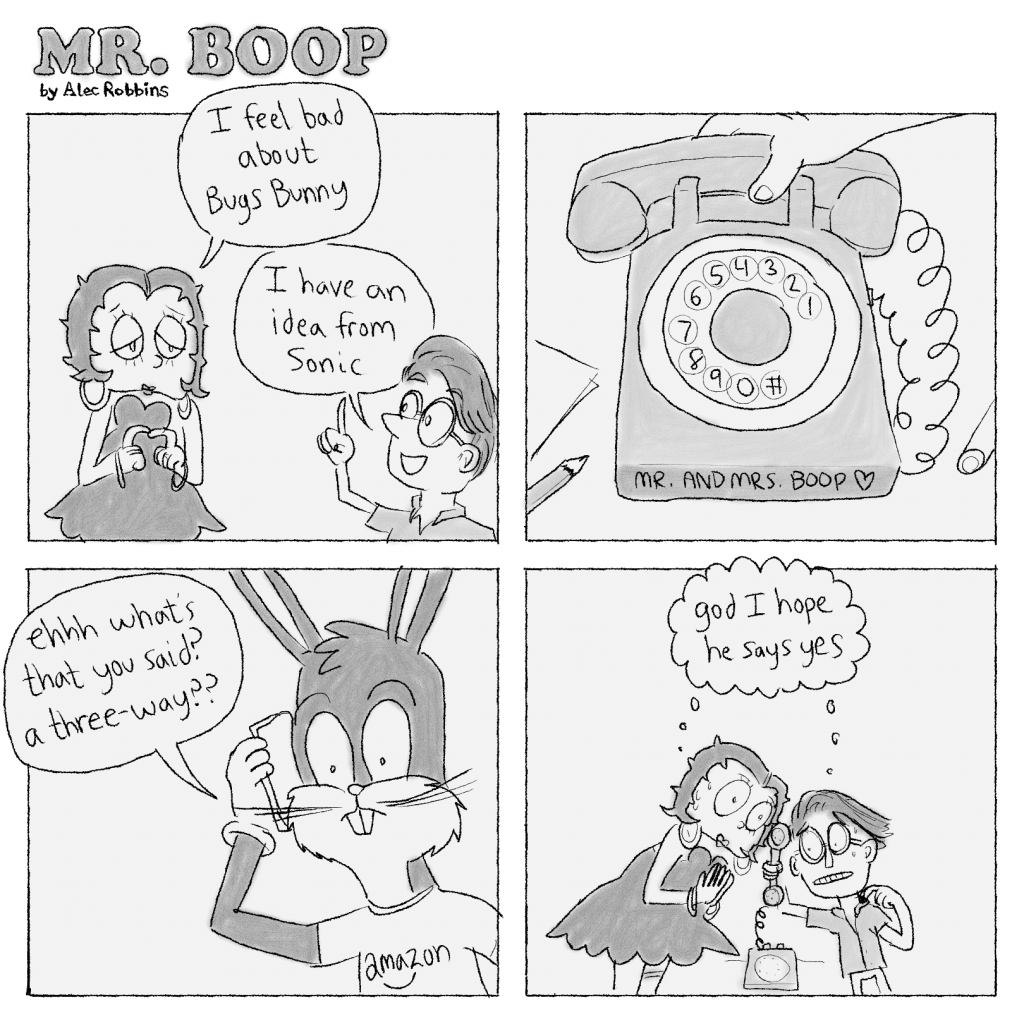

Mr. Boop is written and drawn by Alec Robbins, and is described by the author as documenting his life married to Betty Boop. Alec works at Subway with Peter Griffin and Bugs Bunny, drinks at a bar tended by Sonic the Hedgehog, and has a threesome with Gina from Porco Russo amongst others; these events are recorded in the comic in addition to the inner monologues and motivations of the characters present. Robbins is in an interesting position to document the Mr. Boop universe, as it contains himself and his menagerie of cartoon companions, without holding (probably) the rights to any of the characters in Mr. Boop beyond his own likeness. Robbins has worked in the greater entertainment industry on various projects, including Adult Swim’s The Eric Andre Show; the juxtaposition of Robbin’s reality on his resume and the reality he lives in the comic is the driving force of Mr. Boop. While Alec insists the comic is reality – both in the comic itself and in a video interview posted to his Twitter and Instagram – the world of Mr. Boop begins to collapse in such a way that belies its unreliable narrator.

Initially, the inconsistencies appear to be a function of the concept, similar to Tammy Pierce is Unloveable, in which Esther Pearl Watson adapts a found teenager’s diary and later attributes the “characters”‘ inconsistent treatment of Tammy to their age. In the world of Mr. Boop, everybody wants to fuck Alec’s wife, Betty Boop, and utilizing his expansive cast, Alec and Betty do just that with a variety of funny cartoon animals, anime characters, and adult animated sitcom protagonists. Robbins amplifies already ridiculous soap opera storyline hooks by bringing in characters from all over media in the expansion of his own absurd universe. Some of the funniest moments in the comic emerge from Mr. Boop‘s intersection with those outside of the expected realms of video games and animation, such as “Gina from Porco Russo” (who Alec is careful to specify as such, every time he mentions her.)

Robbins squashes and stretches reality; some scenes feel like reality despite the inescapable ridiculousness of the whole thing. Alec crying at Subway, while his coworkers (Bugs Bunny and Peter Griffin) attempt to console him, could just as well be a scene from Noah Van Sciver’s “I Don’t Actually Hate You” as they accurately portray conversations in the realm of restaurant work; the scenes at Sonic’s bar could easily be taken from an artist’s daily autobio strips.

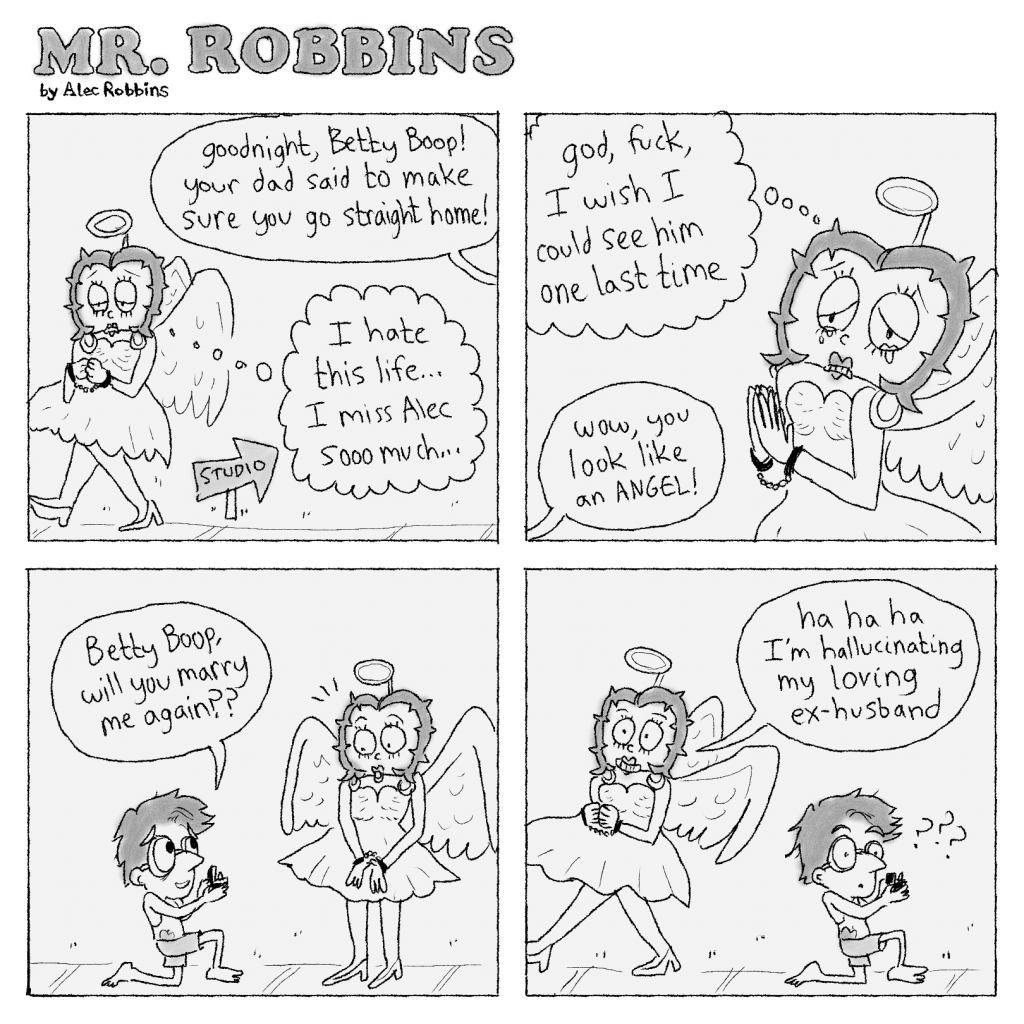

Eventually, after a sequence of violent and sexy events, a cease and desist letter from Betty Boop’s copyright holder — “Betty Boop’s dad” — forces Alec to leave Betty Boop. This twist marks a shift in tone and style as he documents mourning the loss of his marriage and old life. Over time, the reader – and those around Alec – see shifts in tone and style as first revealing the possibility of another reality, and then belying it. It becomes clear that the comics are not reality unto itself, but a veil, concealing a greater emotional reality behind it, a reality that could only be accurately constructed with copyrighted characters, like Betty Boop.

The comic culminates with the meeting of all these realities – the reality of the absurd Mr. Boop, of the subdued Mr. Robbins, of the video interviews – and Alec prompting himself to see the emotional truth that lies behind all of them in an homage that marries Homestuck and the End of Evangelion.

Alec uses copyrighted characters as symbols to construct an alternate reality to shield himself from an emotional truth; Betty Boop’s dad, her copyright holder, insists this is wrong and separates them from each other. Property holders are protective, usually only allowing their charges to exit their own reality and enter that of another for a purpose that will result in profit. Many “official” cartoon crossovers are spiritless cashgrabs or unabashed propaganda; is Betty Boop fucking Bugs Bunny and Goku and Sonic the Hedgehog really worse than that?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply