I have found myself in the position of having a very difficult time with the popular web/print comic, perhaps the marquee comic of this type for summer 2020, Mr. Boop by Alec Robbins. As you are probably aware, Mr. Boop took internet comic circles by storm over the long quarantine with its referential qualities, gratuitous sex scenes, and general irreverence toward a landscape of popular intellectual property of which we are almost certainly familiar. The constant refrain “I love fucking my wife Betty Boop” is probably a sentence I read thousands of times during the months of the comic’s serialization. Nevertheless, and either due to a sense of self-seriousness, which I suppose I’m entitled to, or a contrarianism, that I’m less certain that I am entitled to, I never thought it was very funny, much less disturbing or profound. The question of why not, I hope to explain, though I’m equally interested in expressing that none of this is grounded in a holistically objective opinion. In fact, I’m quite disappointed I have this opinion about a comic so thoroughly and publicly enjoyed. In short: it’s not you, it’s me.

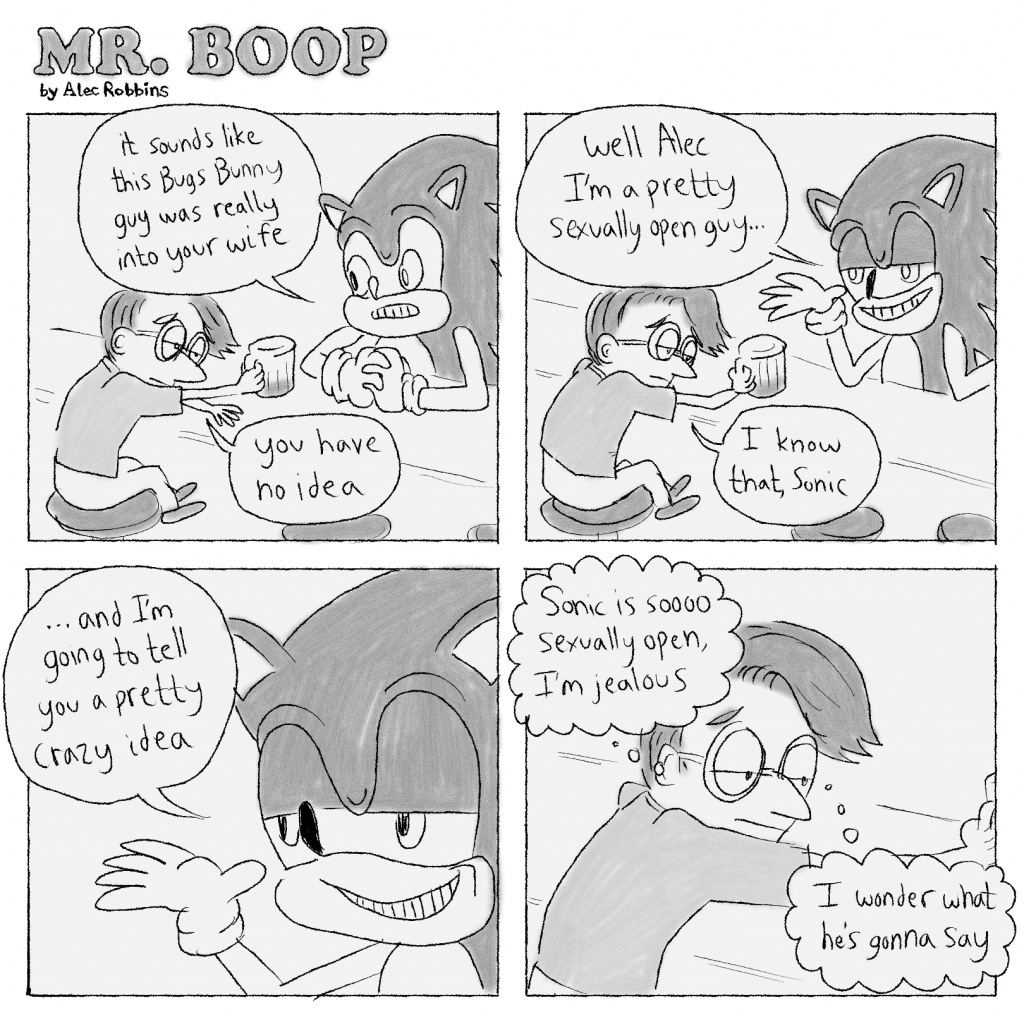

The basic load-bearing objects of reference present in Robbin’s Mr. Boop are Tails Gets Trolled and Neon Genesis Evangelion. Both of these pieces are laser-pointed millennial touchstones of cultural enjoyment that, if you are currently between the ages of twenty-four and forty, and have spent significant time on any iteration of the social internet, you, no doubt, have some sort of relationship with. For me, this is certainly the case, as I watched NGE in my late adolescence and enjoyed Tails Gets Trolled intermittently beginning with stumbling on the comic when I was in middle school. Tails Gets Trolled is the more buried of the forerunners of Mr. Boop and is certainly the more obscure and contentious property. For those who aren’t familiar: Tails Gets Trolled prominently features characters like Sonic, Bugs Bunny, Spyro, Chester Cheetah, Miss Piggy, Mario, and many other beloved characters. It’s a high-pastiche of media properties who talk like they are thirteen-year-old internet dwellers. It’s very funny, definitely problematic, and extremely influential. Mr. Boop is drenched in Tails Gets Trolled as it basically has the same central concept except the characters talk like they are underemployed millennials which, not for nothing, makes Robbins’s Peter Griffin say some relatable things every now and again. This is not to say that the delivery exactly mirrors Lazorb0t’s internet masterpiece, it really doesn’t, Robbins’s four-panel grid and heavy grey pencil style is unique enough to skirt any accusations of overt plagiarism. Furthermore, Tails is notoriously long-winded and Mr. Boop’s quips snap to repetition and fast-paced reading. The intention of drawing this reference is to bring attention to the spirit of this comic as it is manifested in this newer, vastly more popular, iteration of internet-irony jargon.

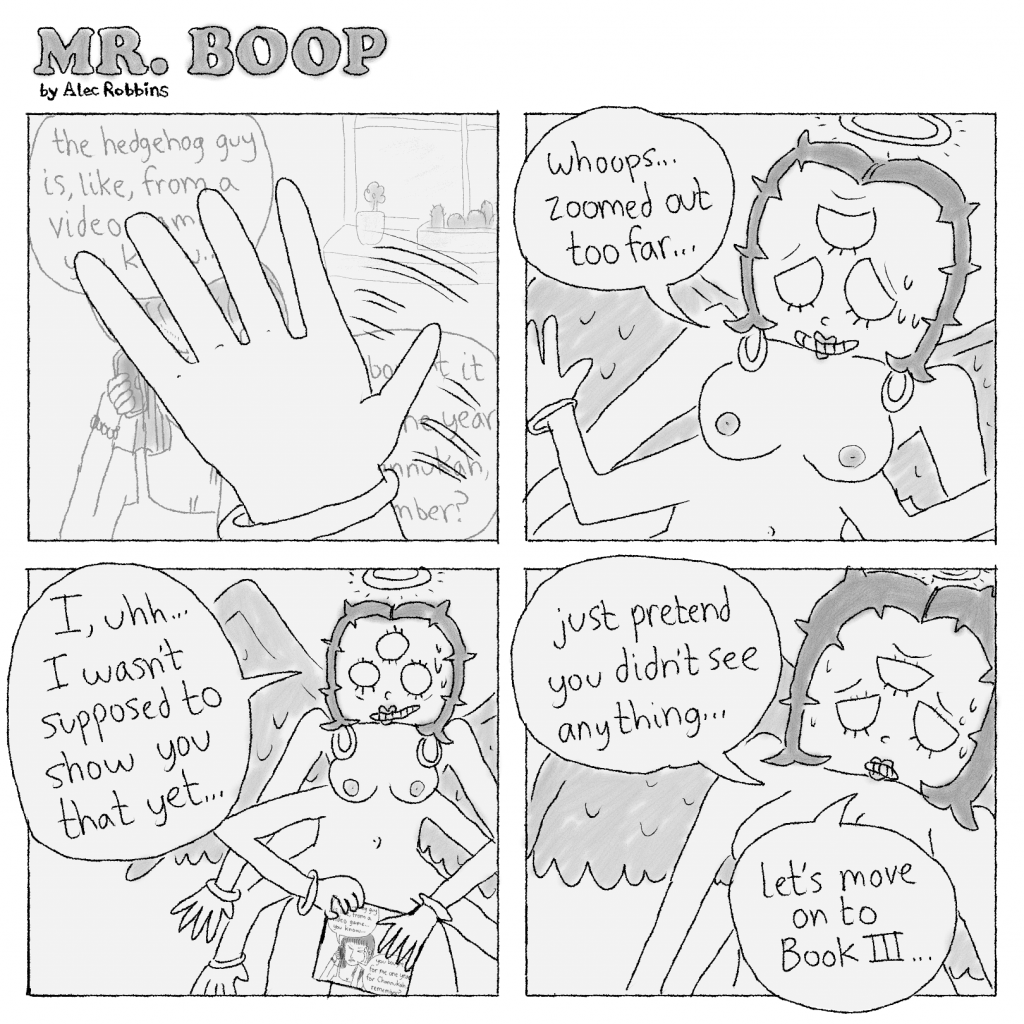

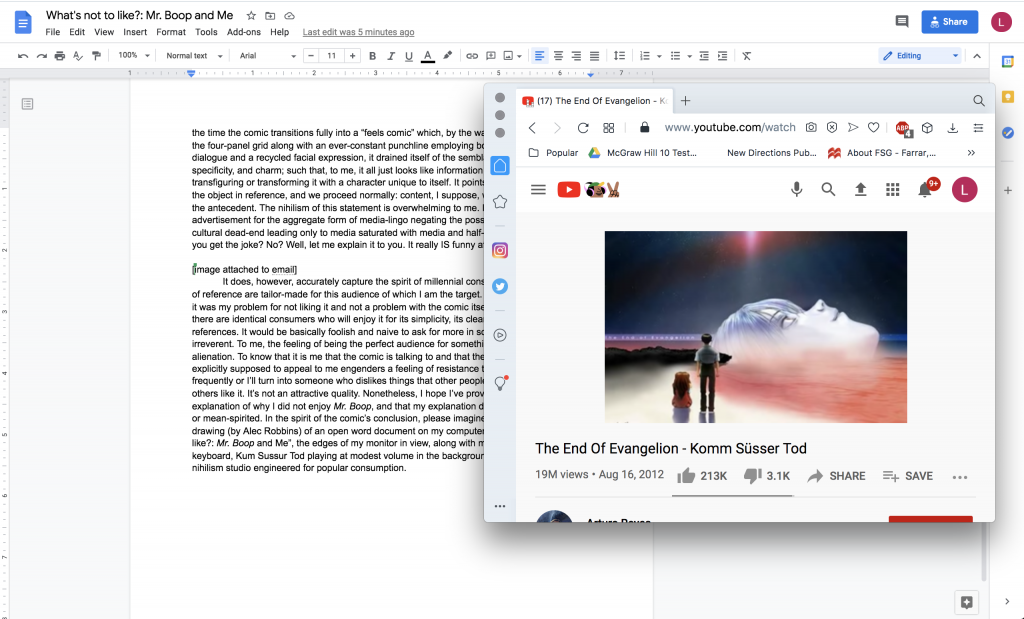

The other axis of referentiality that Mr. Boop operates with is its overt references to Neon Genesis Evangelion which, more or less, serve to give the comic an emotional tether transcending whatever irony-showcase would have resulted had Evangelion not been employed. Beyond the visual references of Betty Boop as Lillith, or Kum Sussur Tod playing in the background during the “Mr. Boop Finale”, the thematic question posed by the End of Evangelion or Episode 24 (“What is real? Isn’t reality better if our wishes and desires are fulfilled to our liking?) is also the thematic core of Mr. Boop, sort of. In any case, the comic reasonably implies that the reader has seen Neon Genesis Evangelion or, at least, has seen that gif of Asuka and Rei clapping with the caption “Congratulations” popping up on the screen. If it doesn’t imply this, then its comprehension basically depends on it.

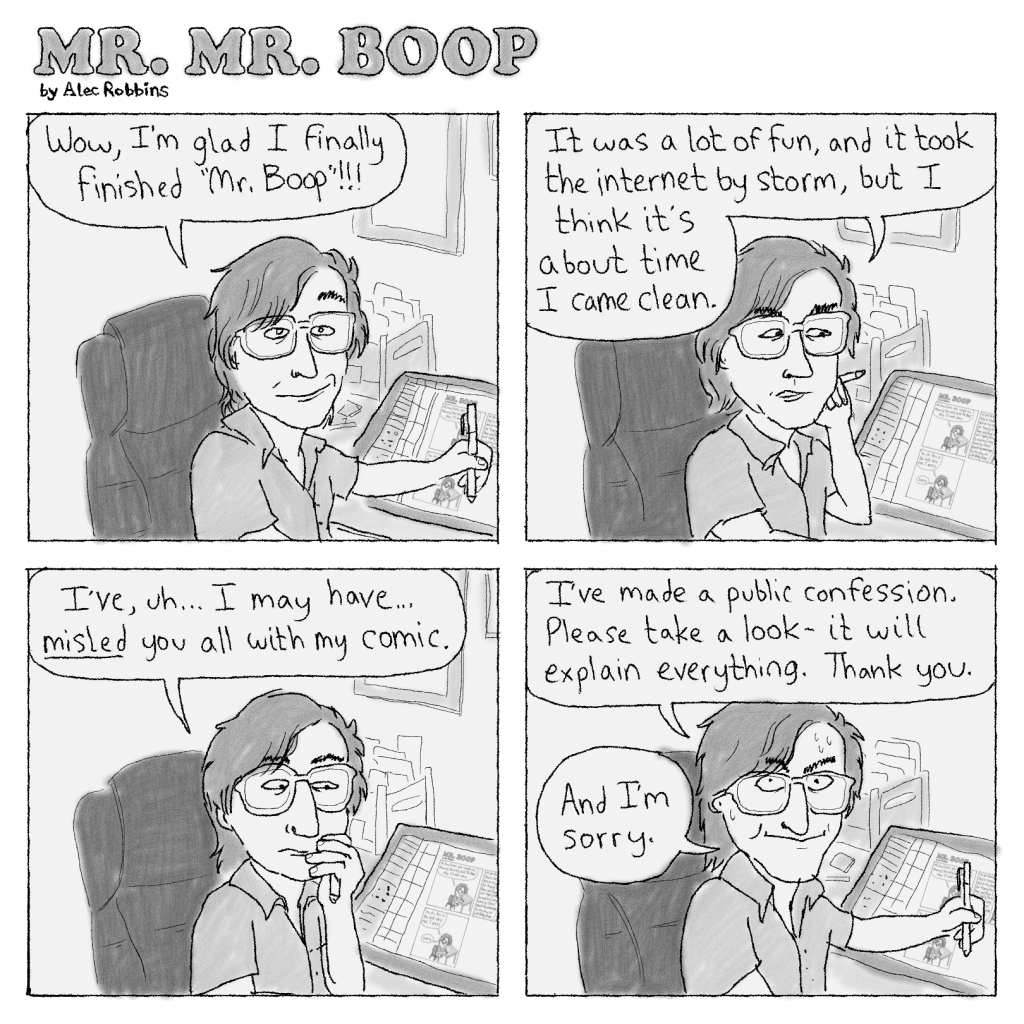

With the hodge-podge of media information that this comic is, I struggle to see how any of the disparate thematics of the work arrive anywhere at the time of its conclusion. I was reasonably interested in Mr. Boop at the outset and remember laughing here and there at it, but at a certain point the comic shifts the reality to actual reality and backloads its theoretical content. Alec Robbins speaks directly to the camera (à la Grant Morrison’s Animal Man cameo) and explains that he wasn’t ever Mr. Boop’s husband, that this is all a comic that he’s drawing.

By questioning its own reality, the comic prompts a brief foray into Alec Robbins’s daily life. It becomes a different extremely popular format of content delivery: an auto-bio comic. Subsequently, it goes back to the fantasy and prompts the reader to consider which of these is “reality”. The truth, of course, is that the auto-bio format was no more real than when cartoon Alec was “fucking [his] wife Betty Boop”, and so on, and so forth. In the abstract, this constructs a worldview. The comic’s statement is that reality is predicated on engagement with media. The type of engagement (e.g. the mode of Tails Gets Trolled in the outset of the comic makes the world a wacky pastiche, the ‘real’ ‘auto-bio’ engagement presents the realities of Covid-19 protocols and isolation, etc.) dictates the style of the comic in the moment, and this is all quite enticing, theoretically, but the final verdict on this is that this isn’t real, this is just a comic, whereas reality is “real”. Which, of course, we all knew in the first place and never stopped knowing as we read, on our phones, in our houses, or on break at work, in the middle of our actual reality from which this comic ostensibly provided a reprieve. But, unfortunately, the joke is on me because I was never supposed to take this comic seriously in the first place. In so doing I’m misapprehending a piece of art that was supposed to be light and enjoyable.

So, what’s not to like? Amidst the intricate narrative machinery and the standardization of punch-lines into catchphrases, Mr. Boop does, actually, have a great deal to offer. It is possible that my negativity on the subject is a foregone conclusion, but what was missing for me was a touch of genuine emotion that would rise above the standards the comic set for itself — a “weirdo” element that could have cemented the entire series into something genuine, rather than a retread of various forms of comic book consumption or riffs on themes featuring the characters native to these types of storytelling. I can’t shake the fact that the emotions in the comic are just suggestions or in-jokes gesturing toward the archetypes of self-loathing and dissociation we imagine as totems for such feelings And, as satisfying and enjoyable the tingle of recognition is at a cut-away joke of Shinji Ikari on an episode of Family Guy, the relevant emotions have the capacity to be confused or to deteriorate in their proximity to insincerity. By the time the comic transitions fully into a “feels comic” which, by the way, also popularly utilizes the four-panel grid along with an ever-constant punchline employing both a trademark line of dialogue and a recycled facial expression, it drained itself of the semblance of originality, specificity, and charm; such that, to me, it all just looks like information without the hope of transfiguring or transforming it with a character unique to itself. It points at an object, we view the object in reference, and we proceed normally: content, I suppose, with the comprehending the antecedent. The nihilism of this statement is overwhelming to me. It looks like an advertisement for the aggregate form of media-lingo negating the possibility of subversion: a cultural dead-end leading only to media saturated with media and half-smiles implying “Hey, did you get the joke? No? Well, let me explain it to you. It really IS funny after-all”.

It does, however, accurately capture the spirit of millennial consumption, and the objects of reference are tailor-made for this audience of which I am the target. When I said, initially, that it was my problem for not liking it and not a problem with the comic itself, I meant that. Surely, there are identical consumers who will enjoy it for its simplicity, its cleanliness, and its references. It would be basically foolish and naive to ask for more in something so popular and irreverent. To me, the feeling of being the perfect audience for something creates a feeling of alienation. To know that it is me that the comic is talking to and that the language therein is explicitly supposed to appeal to me engenders a feeling of resistance that I cannot validate too frequently or I’ll turn into someone who dislikes things that other people like simply because others like it. It’s not an attractive quality. Nonetheless, I hope I’ve provided an adequate explanation of why I did not enjoy Mr. Boop, and that my explanation did not seem disingenuous or mean-spirited. In the spirit of the comic’s conclusion, please imagine that you are seeing a drawing (by Alec Robbins) of an open word document on my computer entitled “What’s not to like?: Mr. Boop and Me”, the edges of my monitor in view, along with my hands typing on the keyboard, Kum Sussur Tod playing at modest volume in the background: trumpeting a gleeful nihilism studio engineered for popular consumption.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply