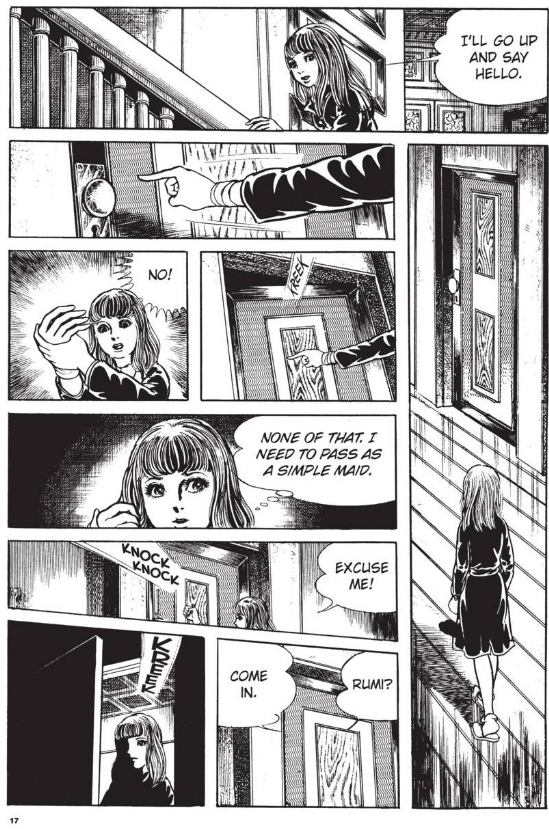

A girl walks in the rain, unbothered by the cold and the wet and the wind. Lightning flashes overhead, and a clap of thunder krakooms in the distance. She comes to a house: old, dark, gated. She rings the bell and out comes a woman – Rumi, as we will find out later. The girl rushes her and, before Rumi can scream, the girl plants her hand on Rumi’s forehead, the pit of her palm inky and cavernous. Rumi’s face relaxes, a new reality superimposed over the old, where she awaited a maid. A maid about the girl’s age and height and look.

A maid named…Orochi.

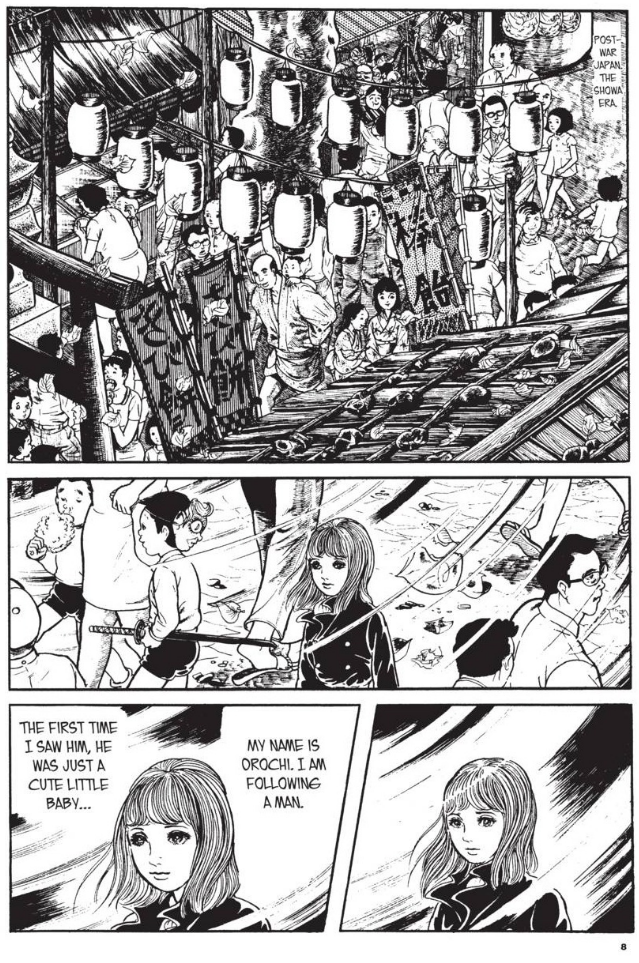

Thus begins the “Sisters,” first published in 1969 by the “god of horror manga” Kazuo Umezz (or Umezu, if you’re feeling feisty). It is the first of nine stories, all created within a year of each other, that make up Orochi. Each story is a standalone tale featuring the titular Orochi, a truly episodic anthology, the only continuity being our understanding of Orochi, or what little of it we get.

Orochi remains an enigma throughout the series. She is capable of mind control, telekinesis, transmogrification, and is seemingly immortal, though, as we learn later, she’s susceptible to a deep, decades-long, comatose-like sleep once every hundred or so years. She floats in and out of the lives of the focal characters of each story, doing very little aside from watching either at a distance or after ingratiating herself with the objects of her interest.

Her reasons for getting embroiled in their (deeply messed-up) lives are left enigmatic as well. No real rhyme or reason is given, though sometimes Umezz will have Orochi give us a perfunctory explanation; in ‘Sisters,’ it’s “to get out of the deluge.” Mind you, this is the story that features (spoilers by the way) a Jane Eyre-esque plot whereby the sisters have locked their mother away in the attic because she is too horrifying to look at having succumbed to the family curse, a curse which strikes every woman in the family at the age of 18 and turns them into a grotesquery, something Emi, the eldest sister, fears as the date of her eighteenth draws ever closer.

Lest you think it’s that straightforward, that’s only part of the first half, and the rest is a twisty series of reveals and reversals regarding the adoptive nature of one of the sisters and the escalating familial abuse that’s taken and heaped upon one another. All the while, Orochi observes from her position, occasionally interfering to satisfy her own curiosity or to protect herself. By the story’s gruesome and tragic end, Orochi has done little to help the sisters but little to hurt them as well. She’s even surprised she helped at all.

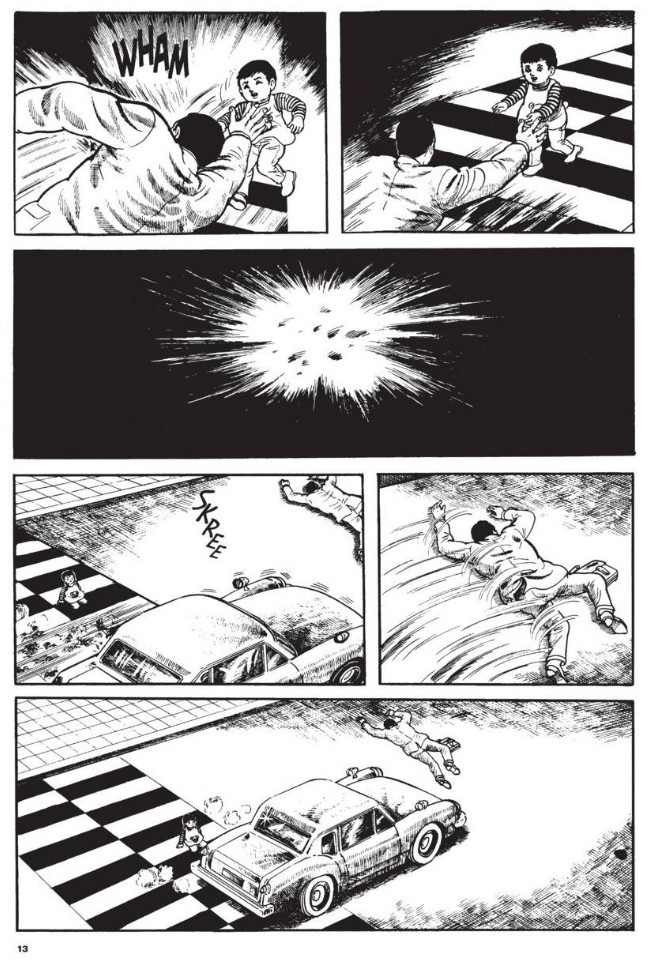

Or take “Stage.” A boy named Yuichi is saved from being hit by a speeding car by his father. His father is killed in the process, and the driver flees. Yuichi identifies him as “the morning man” because he sees the driver on the TV all the time: he’s a famous morning show host named Mr. Tanabe.

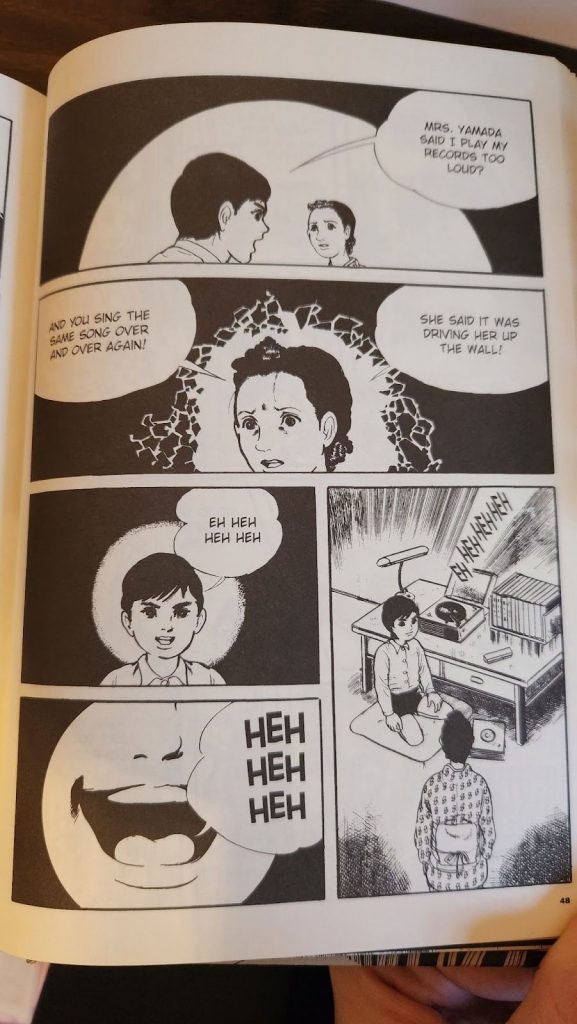

No one believes him, and he grows to hate TV, even smashing his family’s TV with a toy boat. He grows up a little and becomes obsessed with records, saying he wants to be a singer, studying the records of a singer named Hideji Handa. Yuichi is selfish and mean in all the ways a child can be, demanding this, yelling about that, but pushed to almost comedic extremes like stealing money from his mom right in front of her.

Eventually, he joins a reality TV game-show called You Too Can Be a Star! and earns a spot as Hideji’s apprentice by sabotaging the pre-picked winners with hot pepper on the mic and taking a razor to the back of the second place girl’s shirt. The rest of the story is one elaborate escalation after another – psychological manipulation, mercury poisoning – each more dangerous than the last, as the realization fully sets in for us that this is all a revenge scheme for the death of his father.

It sounds silly, but Umezz never lets up, stuffing pages with 12 claustrophobic panels before dropping a splash page of some major, though not always gruesome, development. You may also notice that I never mentioned Orochi at all. Her only contributions to the story are scaring an elementary school-age bully by twisting his arm so much it looks like it could break near the start, and then pointing at the runaway car at the end to stop it, though it still crashes, at the end.

Her reason for doing this? She came across the initial hit-and-run and “decided to follow Yuichi.” The implication is that she feels some form of pity for him, as evidenced by the bully intervention, but that’s the extent of it. These choices left me baffled the first time I read Orochi, in part because I was expecting a story far more similar to Junji Ito’s Tomie.

Expectations. They’ll get you in the end.

A bit of context. The first time I encountered the name Kazuo Umezz was, fittingly, in a story titled “Master Umezz and Me” by Junji Ito from his then-new collection Venus in the Blind Spot. The story is a show of Ito’s comedic chops as he gasses up his favorite horror mangaka, and it got me wondering what this man’s work was like. Well, at the time, the only legal way of accessing that was via a bunch of out of print volumes that I wasn’t going to bother chasing down.

Fast forward a few years, and Viz has since built up a solid library of his more famous – and less controversial – works via their “Perfect Edition” line: Disappearing Classroom, Cat-Eyed Boy, Orochi, and most recently, My Name is Shingo. Reading these books is like being transported to a different world. If you thought Junji Ito had an idiosyncratic style, you should see the guy who inspired him.

Umezz’s characters move across the page like a shadow play: paper cutouts jerked back and forth, stiffly shifting in unnatural ways that reveal the human hand behind it. Their facial expressions, too, are carved into the characters, appearing to almost be swapped out when a new expression is called for and pushed so far as to be read from the cheap seats. That’s not to say he’s incapable of subtlety in his art – the ending page of “Stage” refutes that – he just seems to choose not to.

Normally, this would be a knock against Umezz, a goofy quirk that deflates tension, but in works such as Orochi, this unnaturality increases the tension. He embraces the hyperreality of his world and its stiffness. In doing so, we are left unbalanced and susceptible to the horrors to come. Not the horrors brought upon by Orochi, not the horrors from the supernatural, though it is often present, but from the awfulness of what’s inside us already. Hatred, greed, abuse, obsession, selfishness, cruelty – hatred between sisters being a bookending theme in “Sisters” and “Blood” – all are rife for exploration and Orochi is there to witness them all.

Again, this choice of a mostly passive protagonist fascinates me. It plays against my expectations, as usually the titular character of a horror story is a source of the horror, a prime mover, as it were. In Frankenstein, Carmilla, or as mentioned above, Tomie, the plot revolves around them because they are actively involved.

Each chapter of Tomie is another exploration of how she destroys someone’s life – or, most of the time, how someone destroys their own lives in pursuit of her, and the unnatural and scary lengths they will go to possess her. Often passive, sure, but still the fulcrum around which the narrative revolves. By contrast, Orochi is simply there, occupying a tradition American comics fans are quite familiar with: The Horror Host.

Despite being a staple of early radio and late-night television, the horror host looms large over anthology horror in comics. Most famous is The Crypt Keeper, though other names include Uncle Creepy, Elvira, and Cain and Abel. They are passive framers of the multiple, often short narratives contained in the pages of whatever pulp mag they headline. Orochi, of course, is of the narrative. Her actions have consequences, such as her decision in “Bones” to ease a woman’s distress by reanimating her dead husband, but she is otherwise a shadow in the tale, providing narration and an external POV.

The stories, too, are morality tales, with comeuppance-based horror twists and endings. However, the logic of the stories is not filtered through a tongue-in-cheek wise-cracker who reflects the normative values one expects, but, instead, through the lens of a more childish being. Not a more innocent one, mind you.

Children’s minds simply work differently from adults. They connect things in ways adults refuse to, see things adults don’t because they’re treated as oblivious. The leaps are larger and more tenuous yet easily followable once you know the logic, often one driven by vibes and emotions more than story and continuity. Comedy and horror sit side-by-side, like in “Sisters” when Orochi reaches out to open a door, we assume with her powers, but instead smashes her fist straight through.

It is not subtle either. Graceful transitions? Who needs them? A breathless, matter-of-fact “this then that” presentation and a tendency for hyperbole are what’s most important.

In this light, Orochi makes sense. The stories almost all feature children and ask us to feel the fear of the world through their eyes. A child’s life is all about deep shadows, big, menacing figures, strangers around every corner, and danger lurking behind every door. Taken from outside, from a life long lived, there is something silly about these fears…and yet they’re oh-so real. There may not be an “ugly disease” but that abuse exists, even if all we can see are the pretty faces that hide it.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply