A couple of years back, I was attending SPX with my wife, and she made an interesting observation about how many Jews were tabling on Shabbat. How did we know this was the case? Well, we left with some Rosh Hashanah cards, a small keychain of a golem, and a few other stickers featuring semi-famous rabbinic statements. It struck us as funny more than strange. Of course, we were there doing some very un-shabbosdic things, so who am I to talk?

She didn’t accompany me this year, so I’m sure she was somewhat amused, but maybe not too shocked, when I came home with the complete and unabridged text of Megillat Esther.

Yep. You read that correctly. I picked up the entire text of Megillat Esther in Hebrew at SPX.

To be fair to that statement, it is contained within (or is it around?) an English language graphic novel adaptation of the text. Initially, I thought it was a new book, but the comic is actually celebrating its twentieth anniversary this year with a new printing courtesy of Print-O-Craft, a small Jewish publishing house in Philadelphia.

Truly, this is a book made for me and very few others.

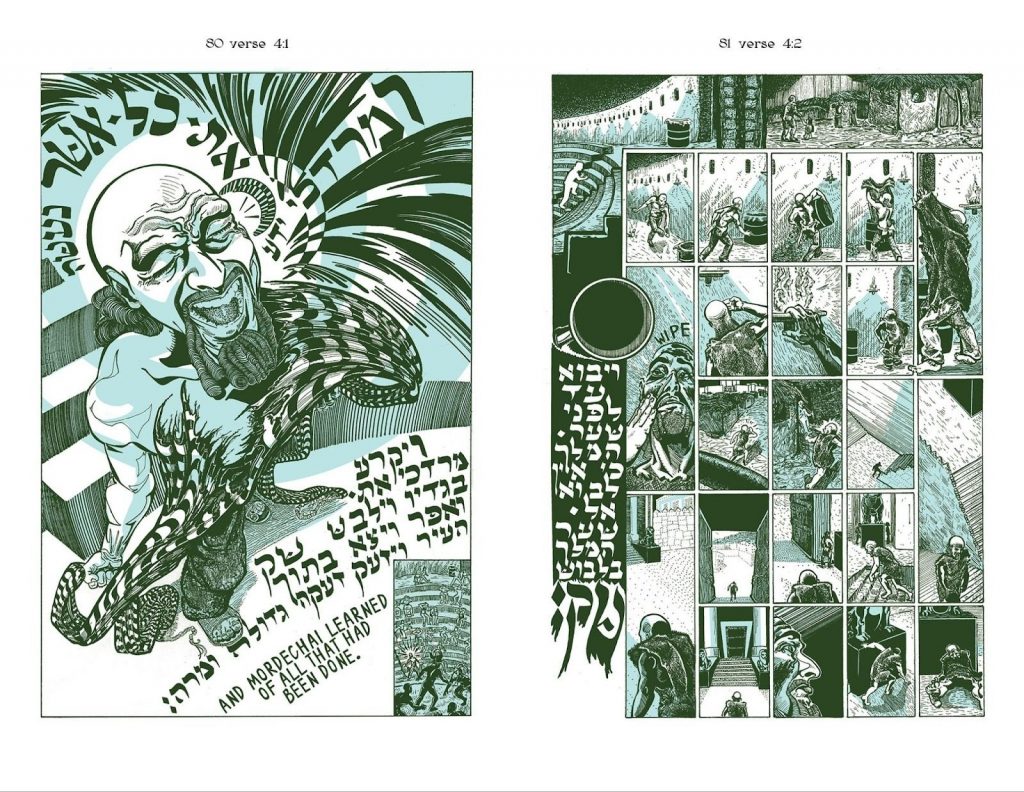

It’s not just the subject matter that is calling forth the ancients. As I just mentioned, each page is composed around the relevant passage from Esther, written out caligraphically in Hebrew, such that every inch of the page is filled with either the original text or its pictographic (and related textual English) representation. No gutter is left unfilled, no panel left unadorned; it’s almost mishnaic in its construction. Perhaps the only page not overflowing in this way is page 57 (verse 2:13), a full-page illustration of Esther in all her finery, looking radiant and regal. “Esther finds favor in the eyes of all who behold her,” indeed.

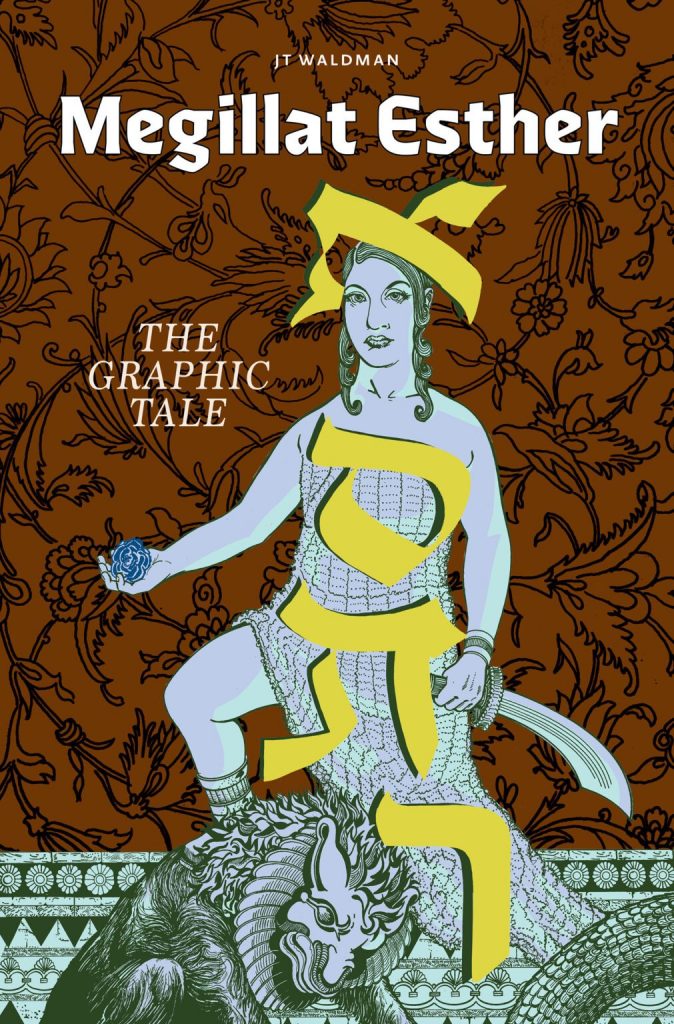

Evocative of other illustrative traditions, Waldman’s Megillat Esther takes its cues from woodblock prints and illuminated manuscripts, in addition to the full-page stylings of Will Eisner. His outlines are often thick, his shading deep, solid, and heavy, sinking into the page, almost as if they walked out of the text surrounding them. Counterbalancing this are the copious amounts of fine details elsewhere.

It is impressive how textured so many of the pages are, particularly the textiles. Rather than clean lines, the patterns are rendered to bring out their hand-stitched, imprecise, intricate, human nature. The same for the characters. Esther looks not like the medieval European imagining of a queen from ancient Persia one might see in a church painting – some idealized, button-nosed, white woman.

Instead, she and the other characters, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, look like people from the Middle East, with varied faces and bodies – somewhat cartoonish in mannerisms and movements to befit the farcical nature of the story, yes, but realistically composed otherwise – complete with hair-styles and fashions rendered from what contemporaneous visual artifacts remain.

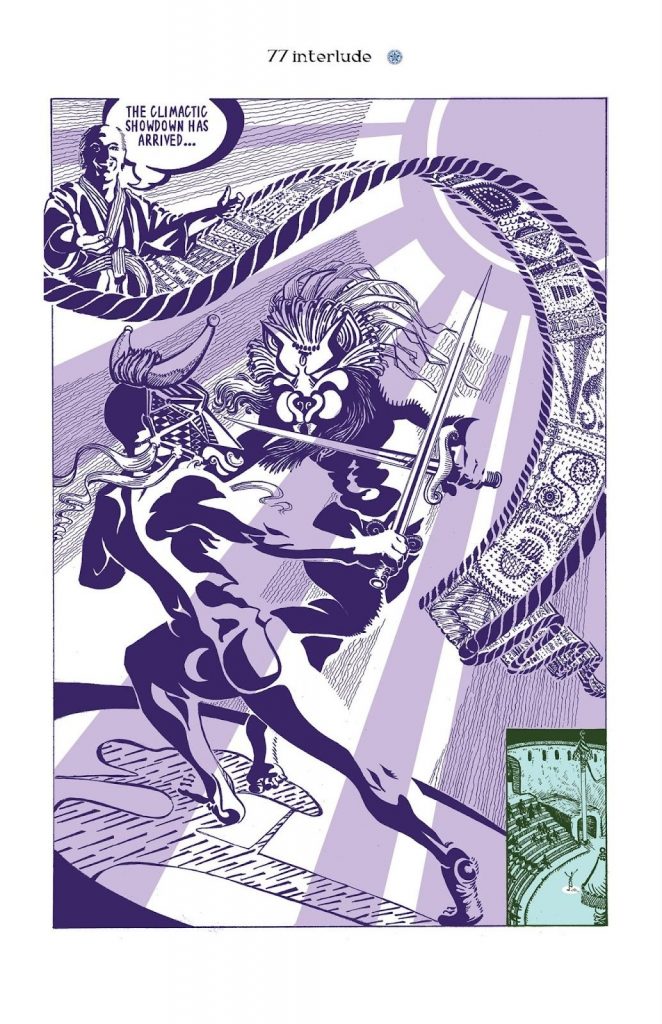

When we enter an interlude or a digression, the visuals change. Sometimes it’s a chalky, almost half-seen shadow-play, other times it’s a pointillist experiment, like looking through an Etch-A-Sketch. They are always less solid than the main narrative, owing to their related yet distant nature. They’re also colored differently, with purples and splashes of orange, rather than the greenish-blue that is the domain of the Megilah.

This should give you a sense of how dense Megillat Esther is. It is stuffed to the gills with references and asides to other biblical stories and midrashim (i.e., rabbinic fan-fiction). For the unfamiliar, it can be easy to get lost in these bits, which distract from the main narrative. In some ways, that’s a problem. In others, it’s kind of a perfect encapsulation of how rabbis approach Jewish texts.

Commentaries upon commentaries, exegesis, arguments, varying interpretations, connecting disparate stories thematically and literally, stories about the stories about the stories about that one guy in the background of chapter 2, there’s a whole world of supplemental material that’s in conversation with the text. Read the brief footnotes in the back, and you’ll only get a glimpse into the ways rabbis have tried to explain or add onto Esther. The number of stories about Vashti alone!

One cannot encounter one without the other. If you didn’t know any better, you’d think we were superhero comic nerds. Maybe this is also why so many Jews are comics readers or why the medium developed the way it did. That is an essay for another day.

Back to the book. Waldman, in making Megilat Esther in conversation with itself and other stories, invites us to dig deeper, question more, and add our own flavors into the narrative. It even questions the more controversial aspects of the book itself, particularly the vengeance narrative that plays out in the final two chapters, and openly highlights the farcical nature of the story, asking how much of the original text is literally true and how much was constructed when the Tanach was being compiled during the Babylonian exile.

It’s a lot even for someone who’s well-versed in the religious minutiae and scholarly arguments like me. I found myself scratching my head more than once, and the chaotic nature of those last couple of chapters left me disoriented. I’m no rabbinic student, sure, but my knowledge runs deep enough and esoteric enough to get the connections once pointed out.

This complexity, the folding in of other works and ideas, serves as a reminder that the comic is an interpretation more than a translation.

Yes, yes. All translation is interpretation, but it’s more than that. In integrating aspects of the midrashim, adapting other stories to act in juxtaposition to the main narrative, and adding metatextual commentary on top of it, Waldman is crafting his version of Esther. A version that honors its roots, engages with its messages, dissects its meanings, and pokes fun at its many ridiculous aspects.

Not every scene is a “perfect” recreation of the text that surrounds it. While the narration feels like a direct translation – archaic phrasing, an oral storyteller’s cadence, that pitter-patter unique to stories like these – the dialogue, particularly within word balloons, is decidedly modern.

His figure’s reactions, too, are interpretive. King Achasverosh giving Haman a particularly nasty look after Esther invites them both to a second feast in chapter 5; Mordechai’s look of surprise and excitement when he learns of Bigtan and Teresh’s plot against the king; Esther’s frustration and fury with Mordechai when he tells her she has to visit the king without an invitation, risking death in doing so. It’s there in the original text to some extent, just not in an explicit manner. Waldman brings it to the fore, transforming inference to expression, and adding another layer to explore.

Of course, that’s what you have to do when adapting to a visual medium, otherwise characters are little more than lifeless puppets, chained to broad descriptions and matter-of-fact recountings. Embellishment is a necessity. When a story is left to moulder in the past, affixed to unchanging interpretation, it becomes stale, lifeless, and disconnected from the now; its lessons (or the tough questions we must ask ourselves) are lost to the wind.

Esther, like so many ancient texts, lives through the retelling. Not made “modern,” but made relevant. Potent. The story of Esther is one of resilience in a time of great strife, of guile and cunning, of survival and mass protest. Of hate-filled advisors plotting genocide and destruction, of a baffoonish king governing by vibes and ego, rubber-stamping atrocities because of (perceived or made-up) slights to his kingliness. Of the bravery of a woman in the face of certain death, using her power to save a people.

What could be more modern than that?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply