“The misplaced love of the common people for the wrong which is done them is a greater force than the cunning of the authorities. It is stronger even than the rigorism of the Hays Office, just as in certain great times in history it has inflamed greater forces that were turned against it, namely, the terror of the tribunals. It calls for Mickey Rooney in preference to the tragic Garbo, for Donald Duck instead of Betty Boop.”

Theodor Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment

“I’m in love with my wife Betty Boop”

Alec Robbins, Mr. Boop

“Art must be free,” or so goes a familiar rallying cry, but free as in speech or free as in beer? Only Alec Robbins dares to answer the call with “both, and also free as in Hot Singles Near You.” More properly, Robbins’ Mr. Boop sits at the intersection of a long tradition of challenges to intellectual property law and the kind of online perversity which invented “Rule 34:” if you can imagine it, there’s porn of it. The plot of Mr. Boop is simple enough: a man is married to Betty Boop™, intellectual property of Fleischer Studios and smokin’ hot babe. Robbins toys with the formulae of “internet wife guy,” a species of cringe-and-cringing male sexuality recognizable for its virality in lieu of virility, and the indie journal comic. Meta wink-and-a-nod video interludes of faux-interviews, where Robbins plays Alec Robbins, the cartoonist behind Mr. Boop, punctuate the strip in its twitter incarnation. Alec Robbins, who in one such interlude stops a “how to draw Betty Boop” demonstration to jerk off, presents his infatuated avatar’s nuptial nonsense in a tightly repetitive four-panel format. The strip is rife with such sitcom standards as “having a threesome with Peter Griffin, from Family Guy™” and “getting shot by Sonic™ the Hedgehog with a sniper rifle, because of sexual jealousy.”

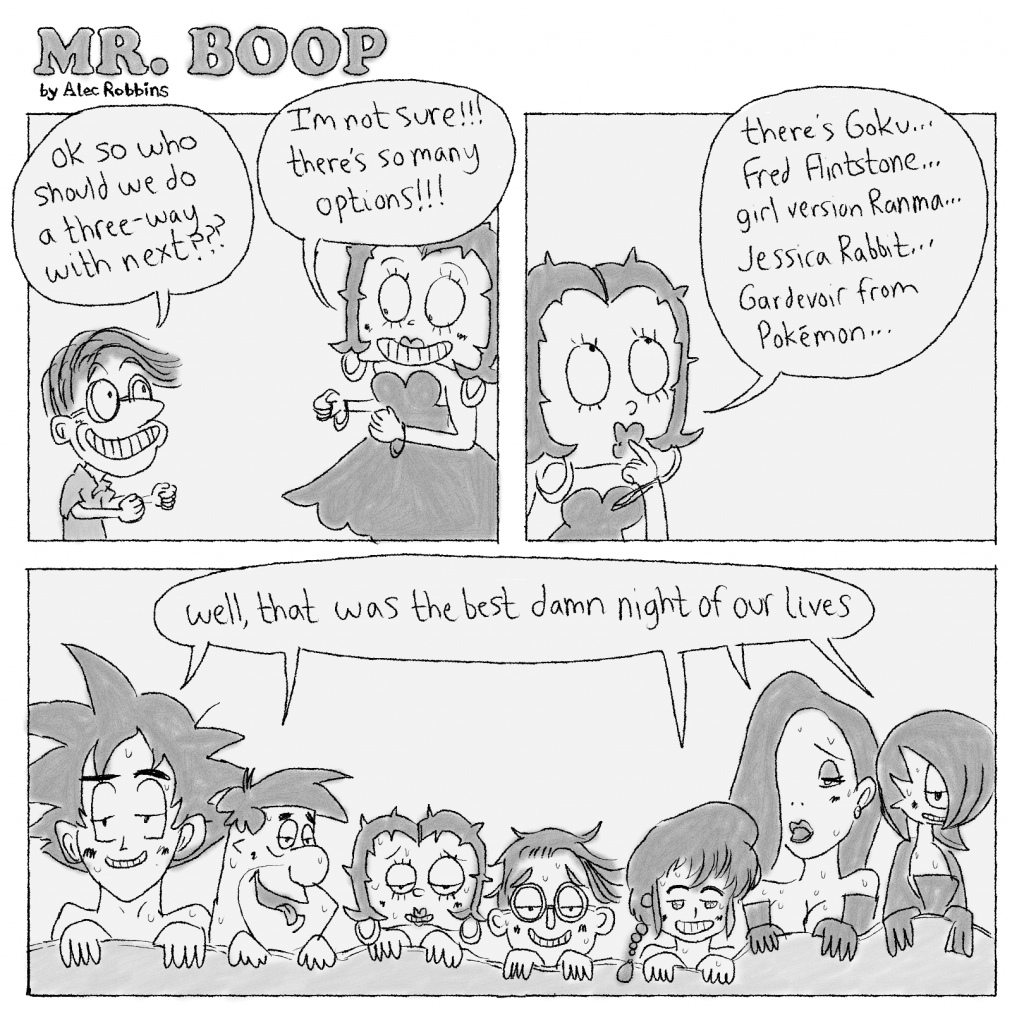

So therein lies the rub, as it were. Robbins draws a range of characters, all trademarked by potentially or frequently litigious companies, engaging in group sex with the Boops, attempting murder, escaping from prison, and so on. Except for a couple of fairly thoroughly cartooned panels including Mickey Mouse™’s erect penis, most of the sex is depicted glancingly, if depicted directly at all. Usually faces, sweating and panting, appear in panel, with characters always clearly recognizable, while the panel border cuts off the specifics. As a result, the specifics of sex itself are mostly underplayed, for all that it constitutes a significant percentage of the text. This is a scandal, not an erotics. Visually, the slightly detached style of the strip emphasizes that yes, this is a joke, and eases the free play of different corporate properties across the same register without disruption. Robbins uses the original cartoon as a likeness and then filters them through a style, which keeps characters instantly recognizable as corporate properties while allowing him to play across different levels of meta-referentiality, which becomes useful as the story focuses more on the corporate law angle, with the CEO of Fleischer as controlling father splitting up the lovebirds, perhaps punning lightly on the marriage license vs the licensing of trademarked intellectual property.

Robbins is playing in a familiar field here, as one thing you are practically guaranteed if you spend any length of time on Twitter is seeing a rendition of a cartoon character in a sexually compromising, or promising, if you’re so inclined, situation. Even that equivocation is suggestive; part of the nature of Twitter is that as a networked platform where content created for one audience on the platform can go viral and reach another, the line between ironic and unironic Sonic the Hedgehog fetish art can be a bit hard to read, and the same image can serve both functions, alternately or simultaneously. Mr. Boop is an intellectually and artistically ambitious comic which uses having sex with Betty Boop™ to think through intertextuality and copyright law, rather than a titillating comic about having sex with Betty Boop™, but none of these examples, we must imagine, are desirable for the brands which hold the copyright for these IPs. Many of these are probably covered by fair use exceptions to copyright, which protect comments on the work. This protection is how sites like SOLRAD can use excerpts from works for review purposes, but also why parodies don’t need to secure licensing rights. Critically, probable impact on the sale of the IP is one factor considered in fair use, so if Disney started selling its own Mickey Mouse fetish art, or if there was a risk that consumers would mistake unlicensed Mickey Mouse fanart for the real thing, the situation might change.

When the Air Pirates, a group of underground cartoonists helmed by Dan O’Neill, produced obscene comics starring Mickey Mouse, “unfair competition” was one of the charges Disney pressed to preserve their trademark. The court ultimately found a copyright violation instead, stating “it is plain that copying a comic book character’s graphic image constitutes copying to an extent sufficient to justify a finding of infringement” Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates, 581 F.2d 751, 756 (9th Cir. 1978). Mickey appears in-comic to rat on the Boops, and he references his overbearing “father” pursuing the Air Pirates case quite directly, suggesting that part of the game of IP theft is a tribute to the Pirates. The Pirates themselves were following an older tradition, that of Tijuana Bibles. These unlicensed pornographic comics, usually featuring syndicated comics characters, were popular through the Great Depression and into the 1940s, but those were less litigious times, and Disney had less to lose. Unlike the Air Pirates, or the fictional Mr. Boop, Tijuana Bibles seldom precipitated any kind of court proceedings. Part of the story here is that American copyright law has become increasingly punitive, with the notoriously litigious Disney leading the charge and with mostly-republican lawmakers happy to collaborate. Derivative art in the digital age can almost certainly rely on being escaping notest one needle in a haystack of perversion and copyright theft, and on host sites having neither the ability nor inclination to remove them. This system works well if you’re doing a parody strip about Betty Boop, but is perhaps more troubling for independent artists when sites like Redbubble allow anyone to upload art they find, from any source.

In the years since the Air Pirates, the reign of the House of Mouse over copyright law seems all but assured, with significant extensions on copyright protections across many different fields, from comics to music. The 1998 Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act extended copyright to the life of the author plus 70 years for works by independent creators, which is how The Great Gatsby arrived in the public domain just a little before its hundredth birthday. Significantly, the restriction on “corporate authored works,” usually really works authored by one or more creators doing work for hire, was extended to 120 years after creation or 95 years after publication. Disney has not hesitated to sue, and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of the same year targeted digital access and reproduction. Despite, or perhaps because of, the increasingly intractable corporate ownership of so much media, an awful lot of media has become metamedia, structured around intertextual references and not infrequently dependent on a certain level of media saturation. The references themselves are unexceptional, as plenty of eager fans are happy to tell you. The comparison usually goes something like this: Older forms of culture are deeply intertextual and reference-dependent, and have been at least as far back as Aristophanes’ various satires on other playwrights. So was Shakespeare not ‘writing fanfic’ of Cleopatra? Ultimately, no. Copyright itself is one critical difference, and with it the assumption that most creative works can and should be not only owned by their respective creators during the creator’s lifetime, but produced, commissioned, and above all owned by companies.

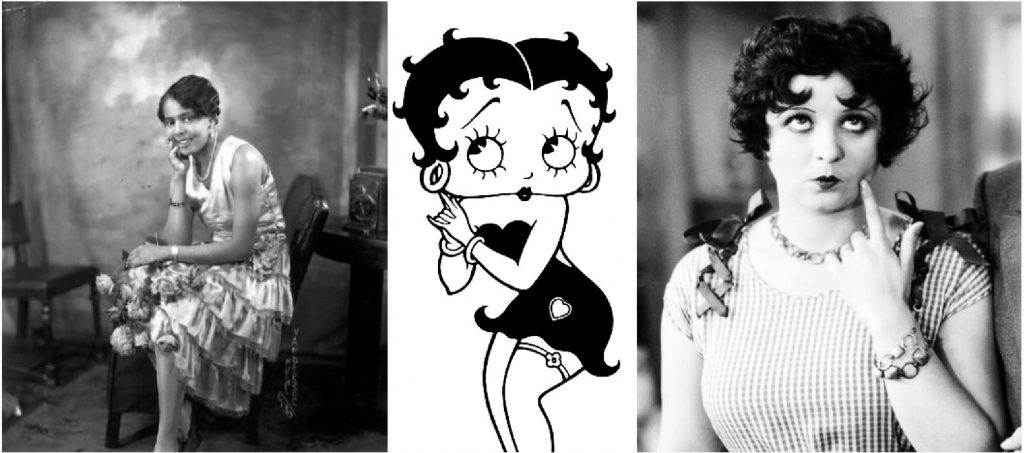

The implications of corporate ownership become starker in another dispute over Betty Boop, this time a real one. In 1932, white singer and actor Helen Kane attempted to sue Fleischer Studios for $150,000 over control of the “boop,” claiming that Fleisher had ripped off her likeness and musical style to create Betty Boop (possibly true), and that she had originated scat singing (which was patently false). Kane was suing for “unfair competition,” recognizing her likeness and style to be a product in competition with other, similar, products, like Betty Boop cartoons. Fleischer Studios responded by submitting evidence that Kane’s own act was “unfair competition” to African American child star Esther Jones, known by her stage name “Little” or “Baby” Esther. Notably, the judge did not suggest that either Fleisher Studios or Helen Kane give Baby Esther $150,000 for the exploitation of her likeness or unfair competition. The “theft” of Kane’s image, which created a rival product in Betty Boop, the intellectual property of Fleisher Studio, was in fact part of a longer tradition, what we might call “cultural appropriation.” In this case “unfair competition” seems more honest and direct, since Baby Esther’s image was used only to disprove another artist’s right to her own image. Helen Kane, by virtue- so to speak- of her whiteness felt entitled to secure a copyright on an act she had borrowed, if not from Baby Esther directly, then certainly from Black scat and jazz singers.

Another “theft” underwrites Fleisher Studios’ work, one more common to early animation generally, which is from the minstrel show. This was relatively big news a few years back when the videogame Cuphead borrowed stylistically from Fleischer Studios without seriously reckoning with the historical origins of the style. As Yussef Cole and Samantha Blackmon explained at the time, it’s not possible to simply lift a style out of its historical connotations. Cuphead, with its gambling Devil and Jazz-inspired tunes, tried to treat the specific imagery of a racist cartoon repertoire as just a stylish shorthand for the 1930s, without further baggage. The baggage can’t be left behind; as Nicholas Sammond points out in Birth of an Industry, figures like Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse are visually derived in part from blackface tropes, their oversized gloves common to “dandy” characters in minstrel shows, still familiar to audiences as Vaudeville shows when Fleischer Studios created Betty Boop. These traits became residual in part because of the presence of much more obvious derogatory racial caricatures, present within the Fleischer Studios’ cartoons as well. Sammond uses “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal You” as an example, with its use of “the generic cannibals common to the racist imaginary of early twentieth century America” (205). This generic racism is made more concrete with the use of dissolves between cannibals and Louis Armstrong and members of the jazz ensemble with whom he played the title song, meant to create a strong visual link for the audience between the band and the cannibals. Sammond notes that Fleischer studios did use recurring minstrel characters in Betty Boop cartoons, like KoKo the clown and Bimbo the dog. Betty Boop herself, a white character, is now mostly remembered for the jazz style in Fleischer’s 1933 take on Snow White, where KoKo is rotoscoped over Cab Calloway. Betty is based on a white artist imitating Black music, and desire for her reminds us of the violence of white desire for Blackness and for Black art. So, if Max Fleischer is Betty’s “Dad,” is Baby Esther or Helen Kane her rightful mother? And what would she make of Alec’s desire? Is it qualitatively the same as Fleischer’s desire to possess Betty Boop, as audiences’ desire to possess and be possessed by intellectual properties, as Helen Kane’s desire to possess Baby Esther’s style?

The problem of desire animates much of this text, in the slippage between consumer desire and sexual desire. How different is the kind of identity-forming attachment that animates the pleasures of something like Ready Player One and the Snyder Cut and marriage to Betty Boop? In one strip, Betty Boop is listing possible partners for an orgy: “Goku… Fred Flinstone…. girl version Ranma…. Jessica Rabbit…. Gardevoir from Pokémon….” This is the same kind or role call list of pleasures which animates Ready Player One, an embarrassing and excessive desire to see brands. In the Dialectic of Enlightenment, Theodor Adorno wrote that the culture industry, or the capitalist mass production of entertainment, was like a “ritual of tantalus” offering the object of sexual desire but prohibiting its consummation. In the next panel in Mr. Boop, we do see all of these characters, flushed and sweaty, agreeing how good the sex was. But, for readers, the only pleasure is in the recognition of the brand and the slight thrill of the taboo, like spotting “easter eggs” in a post-credits scene. Even then, the pleasure of expertise and ownership of exclusive knowledge is diluted — Betty had named the trademarked characters moments earlier. The pleasure is similar to the litany of 80s references which animates Ready Player One, pleasure in the presence of familiar products. For the culture industry, the character Alec Robbins is both the ideal consumer and a significant threat because his desire is absolute, created by the culture industry itself but finally exceeding it.

Mr. Boop’s finale is a montage which samples animation directly from each of the corporate properties as the characters are returned to their original media — including the fictional girl from a fictional diary-style strip who Alec had forced to become Betty Boop in the third arc. “Mr. Fleischer,” the fictional CEO of the very real Fleischer Studios, is caught mid-email, ordering Alec to stop using Betty Boop™ in his sexually explicit “little comic strip.” Alec hand-delivers a letter repenting of drawing himself and Betty Boop having “sooooooo” much sex and, most critically, promising to “now always respect big companies from here on out.” The apparent restoration of the order of property is of course satiric- Robbins’ drawing of “Mr. Fleischer” slightly resembles the mustachioed Max Fleischer, who drew himself into his animations and became both corporate entity and corporate image, available as another character for Robbins to play with. The last step is to return the final character to his own genre — Alec Robbins stands up and walks out of a freeze-framed reprisal of the fictional public access show which he had interspersed with his strips on Twitter. All of this is set to “Komm, Süsser Tod” (Come, Sweet Death), recorded for the End of Evangelion, a film which is itself a geek, or terminally online, shorthand for “depressing and weird meta ending.” The chastened character of the author reflects on his position as the architect of his own suffering and corporate IP thief, and elects to do it again by pulling the “camera” out for one more layer of self-reflexive humor.

I said in the first paragraph that Alec Robbins, the character, was a “wife guy.” So part of the joke in Mr. Boop is Alec’s near-total abjection. Early in the strip, Alec suffers from erectile dysfunction out of fear of disappointing Betty, and Alec is in a coma for most of the second season. Alec’s roommates, Peter Griffin from Family Guy and Sonic the Hedgehog, remind him he isn’t good enough for Betty Boop. It is, however, an abjection which he, as the artist, ultimately controls. The penultimate episode of Mr. Boop demonstrates Alec’s equivocation between abjection and power most directly, as a weeping Alec pleads with a weeping Betty to stop hurting him, and Betty explains that he is the only real person there, the person directly in control of what she says and does, and therefore the only one capable of hurting himself, and hurting Betty. Alec Robbins, too, is also a working artist, and you can purchase copies of Mr. Boop for an affordable $16. Where is Alec Robbins in the chain of thefts which undergird the cartoon character he stole?

In the course of trying to write this essay, I’ve cast around a little bit trying to figure out how to read Air Pirates Funnies and/or Mickey Rat for free. I believe the Alexander Street Database underground comics collection may have a digitally accessible version, but subscriptions cost an enormous amount of money — par for the course for academic databases. Like many people seeking paywalled content, including academic work, I have, of course, tried pirate websites. Controversial (please read: dubiously legal) peer-to-peer download sites like The Pirate Bay will often have scans of older comics available, but in this case, I couldn’t find anyone hosting the files. Maybe I’m losing my touch. It was much easier to find and watch Betty Boop episodes; I also pirated my copy of Dialectic of Enlightenment. Most fruitfully, Mr. Boop invites us to consider the problem of desire and possession, and how we are ourselves implicated in our own relationships with these goods and with the copyright laws meant to protect “Betty Boop,” but not Baby Esther. Perhaps a final theft can take place if one of you plagiarizes or resells this essay. If you do, I hope you get rich from it.

Leave a Reply