One of the main topics I cover in my comics is mental health. Specifically, I cover my own experiences dealing with anxiety and depression. I’ve also been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, but there is some disagreement about that among my doctors (it is NOT fun when multiple doctors call you “a unique case”). I am lucky enough to have the proper support network, medical care, and outlet so that I can handle my mental health issues pretty well.

However, that has not always been the case. I lost my teens and my early twenties to depression. I still struggle with my anxiety issues every day. It took a long time to figure out what works for me to deal with this crap. That’s why a lot of the dialogue on the internet about mental health makes me so angry, especially the “relatable comics” I see so often on social media. These things have like 100,000+ likes and a bunch of them are loved by people that are struggling with real tough shit. Plus a lot of the readers of these comics are really young. So when I see bad advice in these comics about self-care, when I see platitudes that are all-encompassing, or when I see an echo chamber of people portraying themselves doing detrimental behavior for the LOLs, I know it can be an incredibly harmful thing.

I want to say before I get into this that some of the people creating these comics are also really young, and I don’t think they are intentionally trying to do harm. It’s actually the opposite. I think their intention is to help people. But there are other comics that are made specifically to attract views and likes so they can generate a profit. These are especially troublesome.

The following are the most common issues I see with these sorts of comics on social media and the potential harm they can elicit:

“We all do this LOL”

An individual comic in this genre isn’t bad in itself, the problem lies in the fact that there are a plethora of comics like this. Here are two examples from Buzzfeed (whose Instagram has 1 million followers):

As long as this generic humor gets people to look at Buzzfeed, they’ll recycle it. The authors of these comics know this stuff is relatable, and they are quick and easy to read and share. It will bring a lot of people to their page. Whether these comics are published by something like Buzzfeed or are posted only to the artists’ own account, they’ll bring a lot of eyes, likes, and followers. The bigger the audience, the greater the chance to monetize. The fact that Buzzfeed churns out these kinds of comics repeatedly, to the point where they are almost identical but with different authors, contributes to the main problem of this kind of work: seeing these types of comics a thousand times over normalizes these feelings and behaviors as completely universal, and, therefore, not treatable. They seem to imply that “Everyone goes through this, so why bother getting treatment?”

While the reason for these comics’ popularity is how relatable they are, there’s an entire spin off of these that we can call “me” vs “other people” mental health comics. There’s been controversy over “me” vs “other girls” Instagram comics in the way that they portray the author as special and different than all other girls. These comics seem to manifest in two ways: the author can be saying “all other girls are perfect and I’m scum”, or they can be saying “all other girls are too vain and vapid, but I’m grounded.” These comics are heavily criticized (rightly) in progressive feminist online communities because they make women compare themselves to each other and tear each other down.

The “me vs other people” mental health comics all follow the same formula. They entail people being happy and “normal” while the author is depressed/anxious/etc. These comics get thousands of likes because we see ourselves in them, but, at the same time, they make it seem that other people don’t deal with this stuff. Only you, the reader, is going through this shit with the author. This can be really isolating. You might not want to openly talk about what you’re struggling with to REAL people in your life who can support you because, as evidenced by these comics, you perceive your mental health struggles as a rare thing.

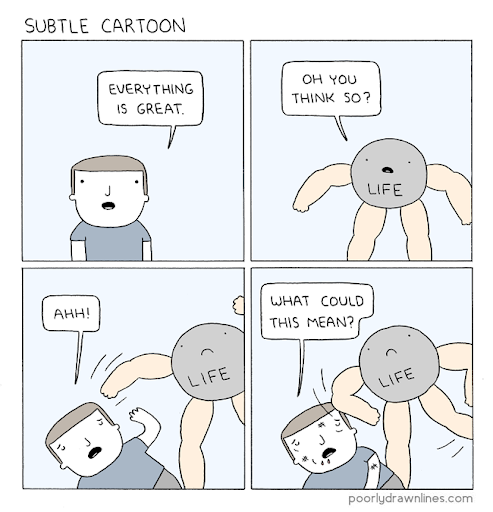

(This “Subtle Cartoon” parody is a good example why Poorly Drawn Lines is one of the best comics on the internet).

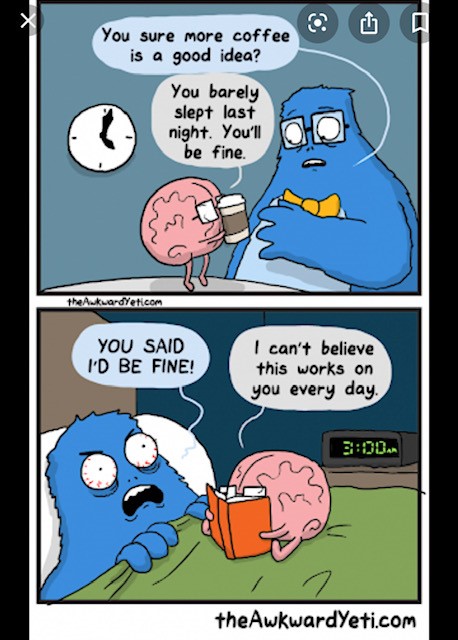

It’s odd, too, because there is an element of “I am special because of my mental health” aspect to these comics. They imply that you struggle more than others because of your mental health issues. You’re a martyr because you survive day-to-day with all of this baggage that no one else has. There’s only you and other people’s mental health in opposition, totally black and white, no grays, no nuance. Still, the comics where people are expressing their feelings isn’t as much of an issue as the ones that show people doing things that contribute to their mental health problems. Google “comic coffee anxiety” or “comic coffee insomnia” and you can see thousands of results. Here’s a bunch (many from Buzzfeed again):

Some of these comics are done well and some of these comics are done poorly (personally, I’m a fan of The Awkward Yeti), but they all say the same thing: “we’re hurting ourselves and you relate to it because we ALL do it.” We live in a society where we feel that we all need to succeed and be ourselves but still be humble, if not self-deprecating. There’s not going to be a lot of people doing comics about the fact that they don’t drink coffee at night and therefore don’t have insomnia. I can’t think of a relatable gag comic about how the author figured out how to have good sleep hygiene. Getting consistently good sleep has dramatic effects on your mental health. But being healthy and taking care of yourself isn’t exactly funny. What can be funny is the shared frustration of the damaging behavior we put ourselves through constantly. Lack of sleep literally kills people, and it can completely wreck your mental health. Compromising on how much sleep a person gets is one of those things that people cognitively understand is detrimental to their well-being, but they don’t take the ramifications to heart and these comics feed into the idea that not being well-rested is a minor inconvenience, not a serious risk factor to all sorts of physical and mental illnesses.

Importantly, one comic portraying this damaging behavior isn’t the issue. It’s that there’s so few counterpoints online that show people actually taking care of themselves that it may not occur to readers that stopping destructive habits like this is important or even an option.

And even within those comics that do show people how to take care of themselves, there are often further problems. Of this genre, there’s the classic:

“Mental Health Tutorial Comics”

While one-off comics that list symptoms of various mental health issues but do not stress seeing a professional in order to get an actual diagnosis are not the worst thing in the world, the comics I really have issues with are ones that talk about coping mechanisms without context.

This has slightly changed recently, but so many of the self-care comics out there just recommend options that only highlight consumerism and, more importantly, avoidance. Yes, you can take a decompression day where you just sit at home, do a facemask, drink tea, and watch Netflix. But if you do that too often, these sorts of behaviors actually become a form of avoidance from the things stressing you out (assuming they are in your control: things like deadlines or looking for work or dealing with issues that need to be talked about in therapy). Instead of providing any real self-care, this behavior has the potential to exacerbate the issue. And even though there are comics that talk about long-form crucial methods of self-care like exercise, hydration, and sleep, they usually don’t talk about how to pace yourself to confront these types of issues.

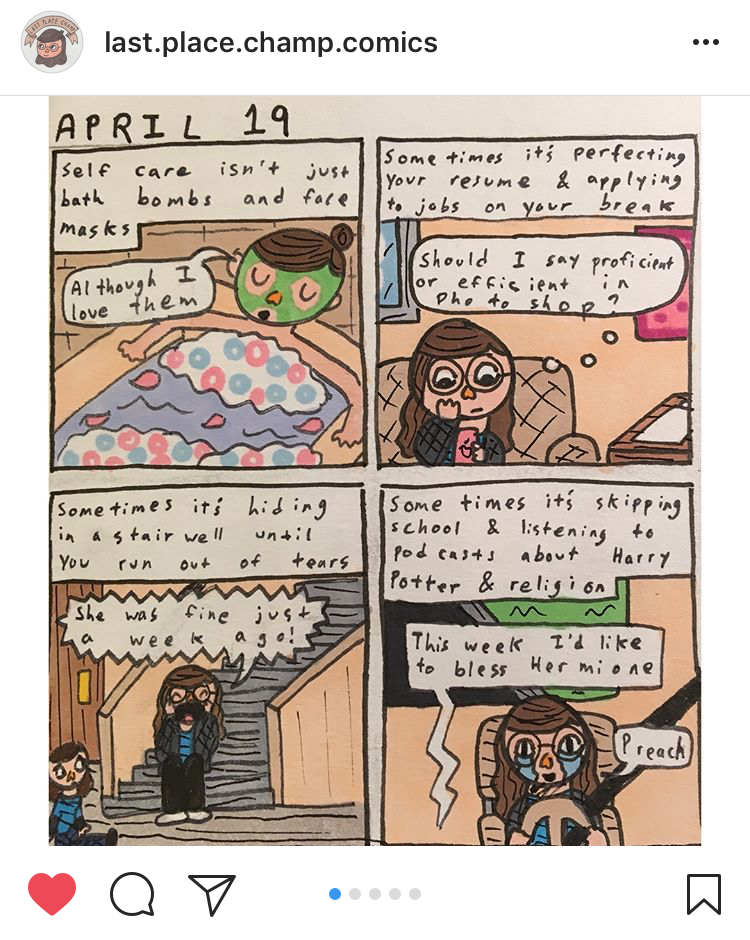

A rare exception to this is last.place.champ.comic which not only deals with the character’s bad work situation by having her apply for new jobs, but also shows her pacing herself by taking a break from class. The key to the success of this comic is that she is describing her own self-care regimen which is helping her own unique issues and not giving general fluffy advice as though the self-care methods they are representing are applicable to everyone reading them.

It’s my experience that sometimes the way to really help yourself is to kick your own ass into getting things done.

Let’s be clear: You’re not gonna be able to do a single panel comic that gives enough advice to actually be helpful. How many comics have you seen that have “seeing a therapist” as a bullet point for self-care, but then don’t say anything about how to find one or get help paying for one? How many comics have told you that you need to drink 8 glasses of water a day, even though that number has been debunked and it’s based on a variety of factors?

There’s a ton of nuance to actual self-care, and it takes years for most people to figure out what works best for them, if they ever do. While there’s a lot of universality to self-care, there’s also specifics depending on the individual. It’s extremely difficult to do a 4 panel comic of advice that actually HELPS people, because the short form leaves little room for the nuance needed to give good advice.

This fact, that we’re individuals, segways nicely into the last kind of mental health comic that drives me nuts (pun intended).

“Platitudes”

You have all seen this type of comic one billion times. The comic is usually something like a cute animal with a general positive message like “I’m proud of you” or “you’re doing great” or “you will get through this.” When these types of things are said by one individual to someone they actually know, it is generally a very helpful and supportive act of kindness that can do wonders for someone’s mental health (unless the people saying this are doing so in an abusive or manipulative way). However, these sentiments are worth nothing when said to millions of strangers.

Some of these comics’ audiences are not doing great and a comic animal shouldn’t be “proud of them”, etc. For example, someone with PTSD from abuse may be continuing the cycle with someone they know, or maybe someone is suffering from borderline personality disorder and is manipulating people, or maybe some of the readers are using their mental illness as an excuse to hurt other people, or maybe someone is not treating their suicidal ideation and it gets the better of them (yeah, that’s dark as fuck but it’s true. Some people do not survive this). A cute drawing of a shark telling them how great they are does not KNOW them; the artist DOESN’T KNOW THEM. It’s not great if someone is doing destructive behavior (whether to themselves or to others), then reads these cute platitudes, feels genuinely validated, and continues that destructive behavior.

And that’s really my point. A lot of people reading these comics don’t realize that their experience is different from the author’s. Each reader is a unique person with a completely different set of circumstances. A lot of impressionable people reading these comics don’t know what issue they are actually struggling with and that there may be help to combat these issues. People see these narratives OVER AND OVER AND OVER to the point that they no longer see it as A narrative, they see it as THE narrative. People who don’t understand their mental health issues are reading these comics that, at best, just add noise to an overcrowded conversation about mental health online and are thinking they are actually doing the best they can to treat themselves because they are following the information they are seeing. It’s not that they don’t have access to more in-depth information, it’s that they DON’T KNOW IT EXISTS. And because these comics are so ubiquitous, they come across as an authority while being incomplete at best, and harmful at worst.

One of the solutions for this is for people making mental health comics to start making them about their own personal situations (such as the last.place.champ comic shown above) instead of ones that are generic and are aiming to be universally relatable. That way, if someone relates to it, they have the context that the struggle being portrayed is a one of many variations in the way that mental health manifests instead of the only way.

That’s really the core issue with these comics. Sure, some of them are harmful in their own right as an individual comic. Platitudes do nothing but harm, even on an individual basis, because they are positive affirmations for all of their readers, and are either disingenuous to readers doing their best or straight up lies to readers that are hurting themselves or others. Same goes for comics with shitty advice about self-care or treatment.

The solution to this is to have a plethora of other types of narratives. The best way to achieve this is by having many different types of people do comics about or based on their individual experiences versus them trying to create comics whose aim is to speak to everyone. While the above comics are relatable to a very wide audience, they do so on a very superficial level. A comic portraying a more individual experience is more authentic and has the potential to make a much deeper impact on people, even if the number of people that relate to it is smaller.

There are good examples of these types of narratives in longer form autobio like The Story of My Tits by Jennifer Hayden or Marbles by Ellen Forney, and they can be seen in more sequential fictional installments like the portrayal of BD’s and his friend Ray Highwater’s post war PTSD in Doonesbury. I think that the fact that these are longer form narratives speaks to the fact that a more nuanced view of mental health takes more than 4 panels to tell. Even if done in individual strips, I think you would need multiple installments to really delve deep and give a better picture than a single gag comic.

The best example of this is Cancer Made Me A Shallower Person by Miriam Engelberg. This book’s narrative is made up of small, individual strips that often are the length of one of the Instagram comics that I’ve focused on in this essay. Lynda Barry felt compelled to make this book the focus of the introduction she wrote for the volume of Best American Comics she edited. While the comic is about Endelberg’s cancer, all aspects of her experience are covered, including the fear and sadness she felt (she passed away after she wrote the book). Her book is quite possibly the most powerful and moving graphic novel I’ve ever read. The strength of the writing and cartooning is evident by the fact that it is published by Harper Collins despite the crude art style. Because this is HER story, and not just generic comics about having cancer aiming to be popular, Endelberg is able to say so much more than the Instagram comics, while being just as (if not more) humorous.

I may be accused of over analyzing these throw away Instagram comics. However, for someone who is really young, comes from a community that doesn’t openly discuss mental health, or is too poor to get access to proper treatment and information about mental health issues (or any combo of the three), the types of comics I’ve discussed are so common and ubiquitous that they may be the only portrayal of mental illness that they see. This is bad for the reasons I’ve outlined above. Having a wider variety of narratives available online, especially ones that are focused on the personal struggles of individuals, have the potential to make the discussion of mental health online so much richer, and are capable of doing so much good.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply