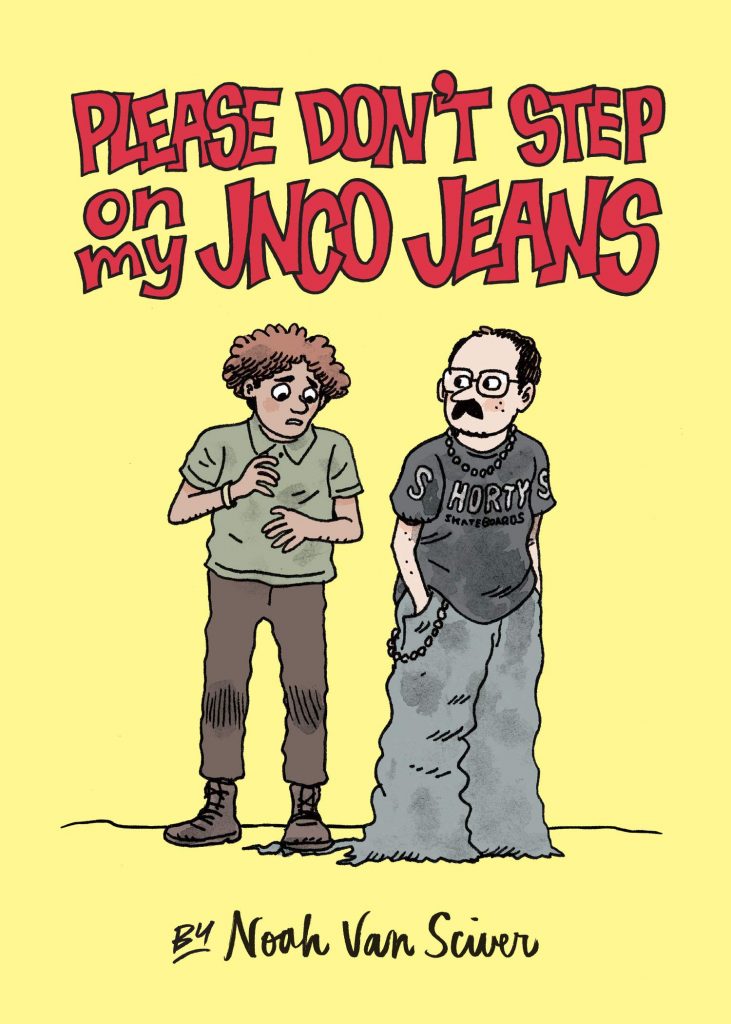

Here’s the thing: people have always said “these days, we could all use a good laugh.” What I take from this is that times have, in one form or another, always been tough, but still — that doesn’t preclude this dusty old saying from being especially true in a year marked by a pandemic, civil unrest, skyrocketing unemployment, and an attempted (if, fortunately, utterly incompetent) election theft. As 2020 winds to a close, we’re a well and truly exhausted society that really could use a good laugh — and, let’s face it, Rudy Giuliani can only provide so many. Fortunately, Noah Van Sciver’s gentle, largely self-effacing humor has always been good for a few chuckles, and so the recent release of his new collection of short strips from Fantagraphics, Please Don’t Step On My JNCO Jeans, is very well-timed, indeed.

Culled, in the main, from his “The Introvert’s Club” strip for the Columbus Alive “alternative” newsweekly, these “comic relief” shorts are all a good few years old now (Van Sciver having moved to South Carolina and the paper itself making the predictable transition to digital-only), but when one’s own life is one’s main source of inspiration, as is the case here, it’s fair to say that the material doesn’t become “dated” so much as it represents a specific period of a person’s existence — or perhaps that should be periods, plural, given that Van Sciver has always been every bit as interested in telling stories about his unconventional and emotionally tumultuous upbringing as he has been about relating his comings and going in the here and now. That “split-screen” set of interests is well represented in the pages of this slim volume, and the division leads to some interesting conclusions both about where Van Sciver was, creatively, in the 2016-2018 (roughly) period.

Looking at Noah Van Sciver’s overall career timeline, it stands to reason that a fair number of these strips were made at the same time he was working on his much-celebrated memoir One Dirty Tree, and he seems to have been very much “dialed in” when it came to formative-years storytelling at this point. Far and away the most effective shorts in this new collection are those set during his childhood, and he seems to have more to say about that part of his life in general — my personal favorite being a six-pager that shows his 14-year-old self going trick-or-treating one more time. He knows he’s outgrown it, sure, but on a less conscious (but no less important) level, he knows that he’d like to hang onto at least the feeling of being a little kid just a bit longer.

There’s a lot to unpack in just a handful of pages in this story, and Van Sciver communicates it all with admirable grace and zero heavy-handedness: his family’s deteriorating financial and social situation, as well as the hyper-sensitive levels of self-awareness that puberty always engenders, were conspiring to make him feel more of an outcast than ever at that point, and so pretending, even for one night, that all is still well, good, and simple in the world is entirely understandable, as well as being a very poignant little memory around which to construct a short strip. Additionally, for those who have read One Dirty Tree and Noah Van Sciver’s Irgnatz-winning My Hot Date, it provides a kind of “connective tissue” between the two works, while at the same time in no way alienating anyone who hasn’t read either or both of them. Another, shorter strip about a stranger who gives him a box of Hostess- or Little Debbie-type snack cakes, which young Noah then duly squirrels away to enjoy later when he’s really hungry, is just as successful and lends credence to the theory that at this point in his creative life, Van Sciver was very much a cartoonist who was finding deep and resonant inspiration by looking to his own past.

By contrast, the strips focused on the fully-grown, adult Noah are more of a mixed bag. Clever and cute more often than not, sure, but overly-reliant on the cheap and easy depiction of himself as a harmless goof who can’t quite negotiate either the current cultural moment or the onset of maturity, responsibility, and a relationship (although always in a safe “gosh, I’m sure trying, though” sort of way), they tend to feel less painfully honest and more determined to present their author as a generally decent guy, forever hopelessly out of step with the world around him. Working to a weekly deadline is necessarily going limit a lot of what one even can accomplish, sure, but the style of his humor likewise shifts when his subject matter does — and again it’s a shift toward the less effective, self-revelation being swapped out for the more comfortable confines of a kind of not-too-terribly-critical form of self-deprecation. Considered in total, the collection reads very much as if Noah Van Sciver is willing to be open and honest about his childhood, but is much more guarded about the version of his adult self he wants readers to see.

That being said, it’s not as if all the strips about Van Sciver’s adult life are a bust — he’s got a gift for well-played comic timing, and so the pure “gag” strips, while admittedly being the kind of thing you’ll only ever read once, are usually good, and he still somehow finds a way to make the stalest premise of all, that of the cartoonist on a deadline doing a strip about being a cartoonist on a deadline, seem reasonably entertaining no matter how inarguably forced it is. And, to his credit, Van Sciver’s instantly-recognizable, populist, “signature” art never looks rushed, even though in many instances it absolutely must have been. Sure, it would be nice if he were as forthcoming and unquestionably sincere about his present as he is about his past; if he were less concerned about creating an audience-friendly image of himself and more comfortable with just expressing himself — but the realist side of me knows that a collection like this is always and invariably going to be a mixed bag. Some limp punchlines and overly-obvious comic set-ups aside, Please Don’t Step On My JMCO Jeans offers a handful of excellent strips, a few clunkers, and a nice smattering of laughs throughout — and, as we’ve already established, we can all do with a few more of those these days.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply