Author’s note: This review contains spoilers for Paul at Home.

I’m an ardent fan of Quebecois cartoonist Michel Rabagliati, whose graphic novels feature an autobiographical protagonist, Paul, navigating life’s passages: losing his virginity in Paul Has a Summer Job (2002), discovering his artistic calling and setting up a household with a long-term mate in Paul Moves Out (2004), and trying to start a family in Paul Goes Fishing (2008). Yet when Solrad co-founder Rob Clough, in a 2017 review on his High-Low blog, found Rabagliati’s Paul Up North (2016) to have “the least amount of depth of any of the books in the series that has spanned nearly 20 years,” I couldn’t disagree. Like Clough, I thought that Paul’s sexism and adolescent snottiness made North less satisfying than Rabagliati’s previous Paul books.

At the beginning of his review, Clough also mentions a possible reason for Paul Up North’s shortcomings: the tumult in Rabagliati’s recent adult life. In an interview with Conan Tobias in Canada’s literary magazine Quill and Quire in May 2016, Rabagliati explained his flagging enthusiasm for autobiographical tales: “My wife and I have been divorced for three years. My dog is dead, my mother’s dead, my father’s ill—my life is really changing and I’m not in the mood to tell that kind of story anymore. I have to do something else.” Maybe North was Rabagliati’s attempt to give his audience a version of his trademark nostalgia, even though he wasn’t “in the mood” for wistful stories. When I read this interview, I realized how emotionally connected I’d become with Rabagliati after reading his books, and I couldn’t imagine the pain of such wrenching losses. I thought about Paul Moves Out, Rabagliati’s sunny chronicle of the beginning of his relationship with his future wife: is a memoir a lie when it all ends unhappily?

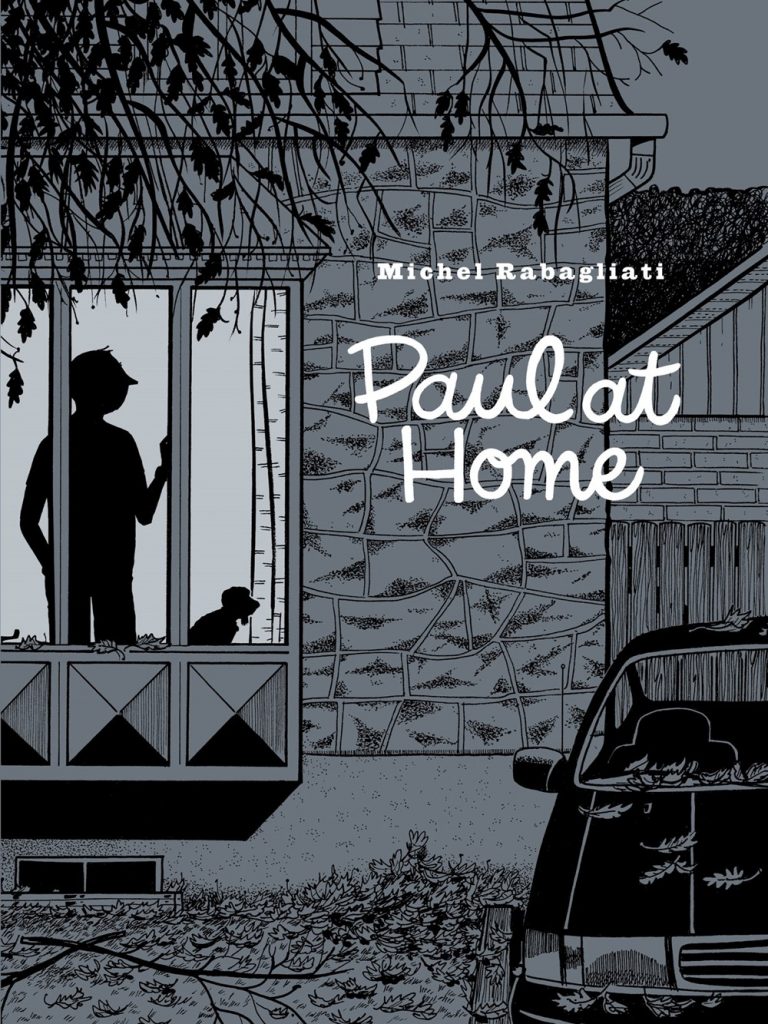

I suspect the Paul books are popular in Canada because they tell stories about a charming protagonist, and because they sentimentally evoke suburban Quebec of the 1970s, which is why I’m curious to see how readers react to Paul at Home, which decisively repudiates Rabagliati’s previous nostalgia. In Home, Rabagliati speaks in relative present tense (events take place in 2012-13) about his depression, his loneliness, and his mother’s death in cynical, relentless detail. It’s a primal scream and a hateful screed against 21st– century culture. It’s one of the angriest and saddest graphic novels I’ve ever read, and feels all the more tragic because Rabagliati’s signature strengths—his detailed cartooning, his playful digressions, his skill at constructing narratives around flash-forwards and repeated motifs—rewrite the optimism of the earlier books and reveal “Paul” / Rabagliati to be a man without hope.

I’ve found that reading the Paul stories as released in English translations—from “Paul, Apprentice Typographer” in Drawn and Quarterly 3 (2000) to Paul Up North—has a powerful cumulative effect, rooted in the patient but consistent revelation of the network of family and friends that surround Paul, and the overall chronology of Paul’s own life. Someone who appears briefly in an earlier work can be supremely important later in the series. Paul’s father-in-law Roland has a one-panel cameo in Paul Moves Out (2005) but becomes the central focus of The Song of Roland (2012). We come to know Paul more with each book too, as each new story fleshes out gaps in his life. Assembling a master timeline of Paul’s life is similar to figuring out the chronologies of Pulp Fiction [1994] and other Hollywood “puzzle films”—and texts like these reward re-readings as our understanding of what-happens-and-when clarifies and deepens.

Re-reading also reveals motifs that pop up in several of the Paul books, One such motif is the death of older people, often mentors for Paul (and presumably for Rabagliati himself). Paul Moves Out opens with Paul and Lucie (then Paul’s girlfriend, later Paul’s wife, finally Paul’s ex-wife) visiting Paul’s great-aunt Janette, a single woman and free spirit who traveled the world and, in Rabagliati’s words, “led a fabulous life.” About three-fourths into Paul Moves Out, Janette dies, and at the funeral Paul imagines Janette delivering a farewell speech from her coffin, happy with her sudden death (“fading away, dragging myself around in a walker, that wasn’t my style…”) and saying “I love you” to Paul one final time. Elsewhere in the book, Paul / Rabagliati eulogizes Jean-Louis Desrosiers, an art professor who introduced Paul to graphic design and highbrow visual culture. Rabagliati’s feelings for Desrosiers are more complicated than his adoration of Janette—there’s an awkward scene in Paul Moves Out where teacher Desrosiers tries to seduce student Paul during a class field trip—but Rabagliati still celebrates Desrosiers for his visionary teaching and renovation of the art school’s curriculum, immediately before noting that Desrosiers died at his country house at the age of 45. A panel visually reduces Desrosiers to an outline of broken dashes, a man vanishing from his garden and from the Earth.

While Rabagliati’s regard for Janette and Desrosiers is clear in how gently and poetically he eulogizes them in Paul Moves Out, perhaps the most spiritually profound death in the Paul books is that of father-in-law Roland in The Song of Roland. Though Roland is reluctant to enter palliative care and his physical decline is not without pain and trouble, Rabagliati nevertheless emphasizes the moments during Roland’s fatal cancer that hint at some deeper significance or feeling. There’s a scene late in the book, for instance, when Roland’s three daughters play music in his hospice room and Roland, in an unresponsive coma, begins to move his fingers and hands in rhythmic time, asserting his connection to life, family, and even basic stimuli while on the verge of death. Rabagliati might sentimentalize death in his earlier graphic novels, but only because its depiction filters through Paul, who focuses on what makes the people he’s lost unique rather than on morbid details and death’s senselessness.

Paul at Home, however, gives us a much more cynical Paul. Unsurprisingly, Home reenacts Rabagliati’s real life and charts the decline and death of Paul’s mother, but the tone of gentle valedictory is gone, replaced by cynicism and anger. Paul hates visiting his mother, Aline, at her senior living apartment, gets frustrated with her static, antisocial lifestyle, vehemently disagrees when Aline refuses chemotherapy, and struggles to connect meaningfully with his mother as she quickly declines. Aline dies alone, her tongue “hanging out the side of her mouth. She was in a morphine coma. It was disturbing and sad.” Rabagliati praises his mother’s polished deathbed appearance—she wears a beautiful dressing gown and her toenails are perfectly manicured—but that’s surface stuff: she neither inspires an epiphany in her son or experiences personal transcendence. Earlier in Home, Paul waits to deposit a check at the bank and analyzes the “good life” posters on display (of older couples smiling and sailing) designed to encourage customers to save money for retirement. Paul’s take: “Who falls for this crap? The truth is, we’re all going to wind up broke and dumped in some old folks’ home, poorly fed and shitting in our pants.” It’s a far fall from dancing hands to shit-filled pants.

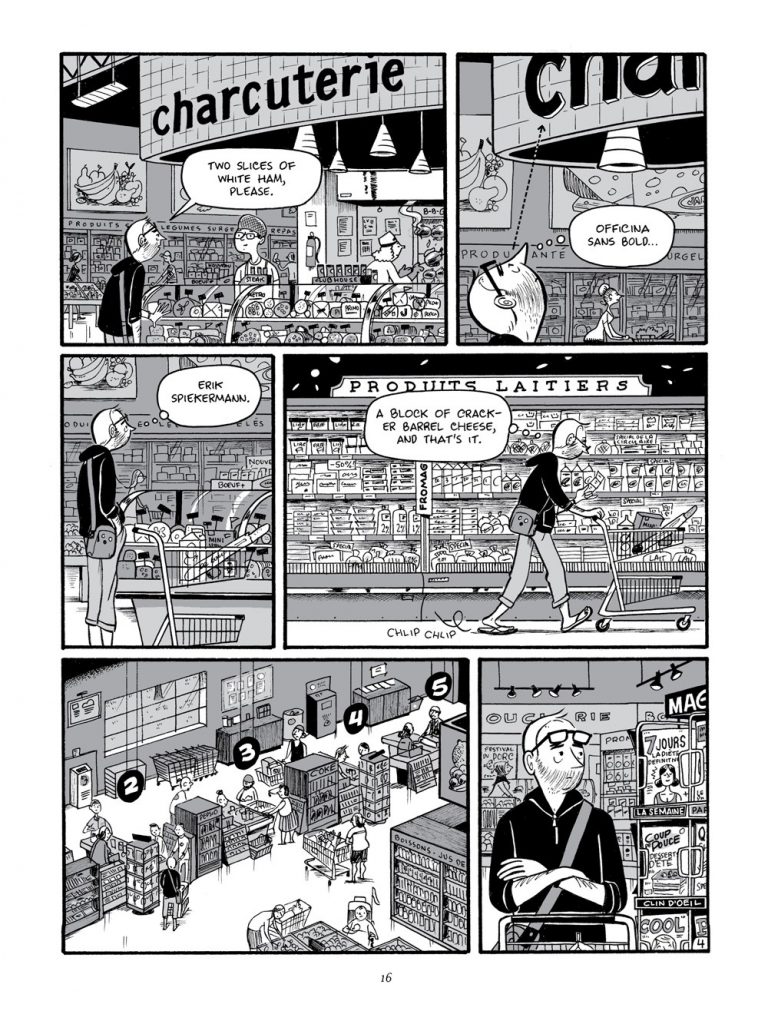

To be fair, some of Rabagliati’s jeremiads in Home have precedents in previous Paul books. One constant is Rabagliati’s hatred for computers. A digression in Paul Goes Fishing (2008) charts the disappearance of typography and color separation skills as graphic designers and printers digitized their disciplines: the result is a treadmill of expensive software and equipment updates that perpetually wring money out of those artisans who managed to adapt, precariously, to the changes. Rabagliati summarizes the situation thusly: “We really got screwed.” In Home, Rabagliati now sees absorptive technology fucking over every facet of modern life. He can’t bear contemporary television: his mother talks about TV celebrities like they’re her only friends, and Paul’s favorite show is the Canadian soap opera Les Belles Histoires des pays d’en haut (1956-1970), which hasn’t produced new episodes in a half-century. Cell phones anger Rabagliati the most. Paul refuses to buy and carry one, and, while riding the bus, he fantasizes about yanking the phones out of the passengers’ hands and pitching them—smash!—into the street. Even Paul’s daydreams are unhappy: after Paul explains his position (“We are surrendering our brains to the arbitrary power of binary code and gigabytes!”), the bus crowd still beats him to death.

I don’t use a cell phone. Like Rabagliati I’m wary of the ways they command our attention and erode social capital. Yet Paul’s disdain of technology extends to devices and procedures—MRI scanners, dental implants, computer dating sites, CPAP machines—that often improve lives. Paul’s techno-hatred is so all-encompassing that it becomes both a mistrust of any social change or shift and a symptom of clinical depression. Another plot in Home involves Paul and Lucie’s daughter Rose, who decides to move to England against her parents’ wishes. As Rose boards the plane, Lucie cries, “Dammit! Why does she have to go?…Why does everything have to go?” That cri du Coeur is shared by Paul, who is confused and angry as the culture and the people he loves are dying or drifting away. While driving Lucie home from the airport, Paul tentatively reaches out to her—“Do you…uh…I dunno…want to go have a drink somewhere?”—but she kindly, firmly turns him down. The next four pages are silent, as Paul walks his dog and despairs over the fact that he is truly alone.

Do I recommend Paul at Home? Absolutely. As usual, Rabagliati’s aesthetic virtues are many: few cartoonists draw backgrounds and urban scenes better, and I continue to love the narrative digressions that define his unique point of view. (One running “joke”—Paul’s obsession with the fonts in his environment—reaches a climax in a two-page rant about the reasons why Highway Gothic was better for road signage than the new Clearview font. Paul ends by yelling “I hate change! Especially when it’s useless!”) It seems callous and irresponsible, though, to discuss Home as if the book is sealed off from its circumstances of creation and reception. It’s an act of courage for Rabagliati to channel his painful 2012-13 desolation into his art, and, on one level, I read Home as a desperate message from a struggling friend. I was less concerned with analyzing Rabagliati’s achievement than hoping that his life has improved. And in giving us a book called Paul at Home, in showing himself unshaven, bitter, and isolated, Rabagliati has unwittingly captured the COVID-era zeitgeist. We all deserve better lives right now.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply