I will begin this review with a list of complaints. Glenn Fleishman’s How Comics Are Made: A Visual History from the Drawing Board to the Printed Page is not exactly the most flashy-written book one can find; the prose usually hovers between a basic-intro text to a slightly excited magazine article. The book’s format doesn’t offer the best reading experience: a page will include a main body of text alongside comics examples, with various ‘asides’ in color boxes; all these different parts don’t always mash together as a singular unit. Like many books about the history of comics (Marvel Comics – The Untold Story, Thrillpower Overload) it gets less and less interesting the closer it gets to the present, both because the author’s interest obviously lies with past events and (one suspects) there’s a certain carefulness not to step on any toes when a living cartoonist is involved1.

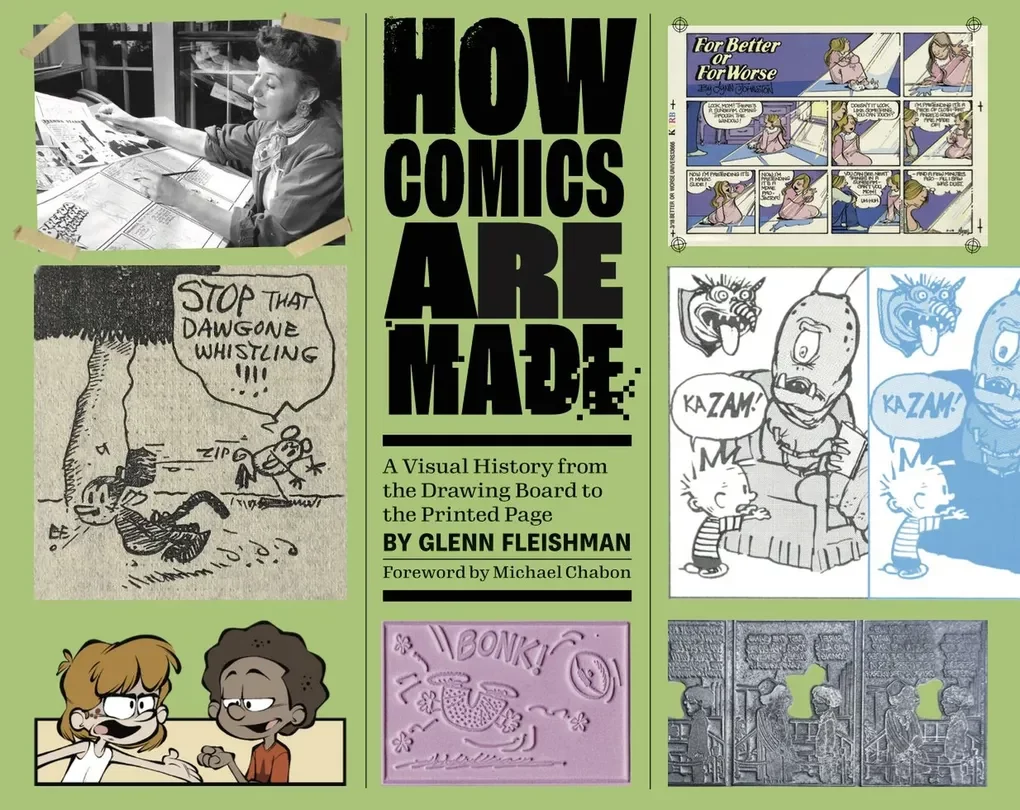

Having got these out of the way, How Comics Are Made: A Visual History from the Drawing Board to the Printed Page is one of these books that I would say is recommended only if ‘you are into that sort of thing.’ This is usually taken as damming with faint praise, so I will make something clear: Dear reader, I am into this sort of thing. I am so into this sort of thing that I might go through a Last Action Hero experience and find myself transported into these pages (wherein I will probably get cursed by a metal presser). Histories of comics, whether of a period, a company, or of a creator, are no longer a rarity. The field is not as wide as I would like it to be, but there are new books published monthly on the subject. I used to be able to keep up with the pace, but the stuff put out by the University Press of Mississippi alone is enough to tire me out. How Comics Are Made offers us something new – a mechanical history, an exploration of the physical process that makes comics strips2 possible. The long, and often strange, journey a strip takes from the pen/pencil/brush of the artist to appearing in the page of your local newspaper.

This journey involves metal, zinc, flongs, presses, plates, and stereotypes (in both meanings of the term). It is a journey that widens our perception of who is ‘the maker’ of comics; I knew that before modern computers, the process theoretically involved many hands, but only after How Comics Are Made did I learn just how vital the engraver, an otherwise nameless individual, was to the reading experience of millions. As Fleishman notes several times throughout this book, through much of its history, the process of making a comics page in a newspaper was so grueling and counter-intuitive that it was nothing less than a miracle (a miracle of extremely talented craftspeople working grueling hours with no credit) that most comics pages came out legible.

This is important, because it centers back comics as what they originally were: a work of popular art. The two parts of the descriptor are, to me, equally important. They were art, oft low-brow art, oft bad art, oft racist art, oft undervalued art, but none of these made them any less works of art. At the same time, comics were defined by being a work that the wide public could experience simultaneously – part of commercial reality: “[C]omics are a creature of mass reproduction[…] Oil paintings hung in one home or gallery; prints from the 1400s to the early 1800s were typically made in small quantities and weren’t cheap. But the advent of technology that allowed drawings to be printed in effectively limitless numbers evoked an art that reflected the audience.”

Much of the history of comics studies was about avoiding this simple truth. The study of that history was instead dedicated to the manufacturing of a more flattering story. People such as Will Eisner and Scott McCloud called it ‘sequential art’ and tried to put it in a wider historical context, which often meant attaching it to older, pre-reproduction works of art. It’s understandable why they did it; the medium as a whole still had to fight to be recognized, but the end result was the creation of this defensive mentality that tried to suppress the less-flattering parts of comics history3. That era is over; we can look at history more clearly now.

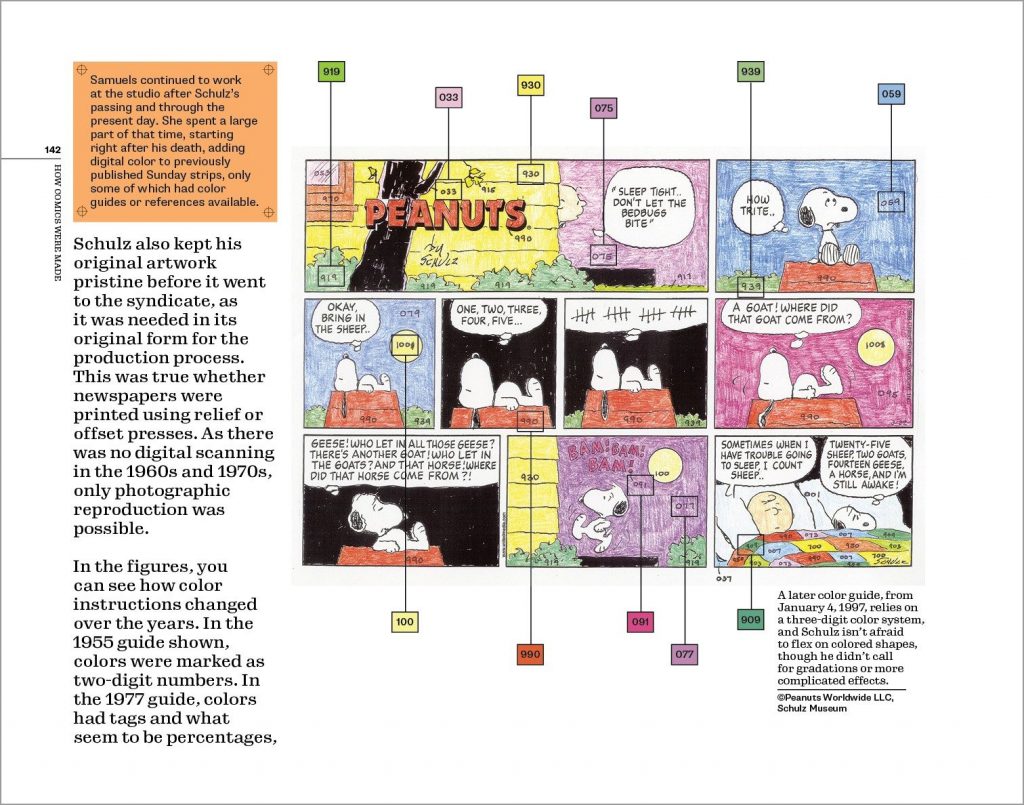

How Comics Are Made doesn’t set out to be a polemic. As previously mentioned, the tone is often school-book naturalistic, going for ‘just the facts, ma’am’ presentation. This might detract from the strength of the prose – you want the book to feel more enflamed and alive – but it opens up the road for a surprisingly materialistic reading of comics history. Much of How Comics Are Made is the depiction of machinery – its construction, its uses, the people who make it go, the sheer physical mass of it in action: “In the 1940s, the New York Times used, for printing plates alone, more than 90,000 pounds of lead alloy each day, and 300,000 pounds for the Sunday edition.” Let these numbers roll in your mind, absorb their sheer physical being, and then consider – all of that for something that will be thrown into the trash one day later. Comics, as we know it today, would not be possible without this otherwise invisible chain of workers. Peanuts is Charles Schulz, yes, but without hundreds and thousands of people working across the nation (across several nations), his work would languish in obscurity. Comics is not museum art, it is mess art. A mess creation and a mess experience.

There is something magical about the pictures found in this book. Their depiction of a world constantly changing and evolving4, but always a world that is present – the machines are massive, the workforce is large, newspapers are printed in their millions, delivered into the houses of about one half of the United States (and read by many more besides). It is wrong to wallow in nostalgia – certainly, few cartoonists featured in this book show any sorrow for the replacement of the physical, mechanical process of comics-making with the mostly digital one. Digital offers more options to the artist (especially when it comes to colors), it makes the process of creation and correction much easier, it opened up the gates to many creators who couldn’t find space in the world of traditional strip-publishing.

At the same time, there’s something oddly fitting about the events in the final chapter of the book: the more digital the process of comics-making (and comics-delivering) becomes, the more ethereal its impact is. The comics page is shrinking alongside the notion of a ‘newspaper.’ There would probably never be, in terms of influence and public recognition, a new Peanuts, or even a new Bringing Up Father. Physical newspapers might have been perishables, but their physical presence seems to have meant something: a sort of communal experience that can’t exist in the splintered world of the internet, where each is free to make a bubble of their own interests5. It’s much easier to read news these days, and to find comics is a matter of a few clicks, yet their exposure is only shrinking6. When the comics page was an object, it had some value – value that is lost when it’s just another piece of streaming data coming on and off your phone screen. When things aren’t tangible, they don’t appear as valuable.

As How Comics Are Made points out, the digital revolution isn’t as revolutionary as people imagined it to be. Quoting web comics creator Brad Guigar: “How do you make a webcomics? The answer is: in print. Because all other stuff is secondary, with Patreon being the notable exception.” Even the most successful of webcomics, your webtoons one-in-thousand phenomenon (Lore Olympus), for example, still craves a physical niche. People read online, but most will pay more for a physical object7.

It’s easy to get lost in the nostalgia trap – the ‘golden age’ notion that is as old as human thought. How Comics Are Made doesn’t get lost in it. The machines are cool, and the various steps shown in the printing process are worth the cost of the book alone8, but Fleishman makes it clear just how difficult the process was. At the same time, the book does not automatically worship the new. Doing things ‘the easy way’ has its own price. In trying to be naturally descriptive, it actually manages to show us the ups and downs of history. There are costs to change; there are also costs for getting stuck in a rut. Robert Warshaw once wrote, “The comic strip has no beginning and no end, only an eternal middle9,” How Comics Are Made shows that is true not only on a plot level, but on a process level as well; they have to keep changing and adapting in order to stay basically the same10. Some of the strips we read today are strips read by our fathers and grandfathers; others are new but work on principles that are over a century old (the four-panel gag comic is seemingly unkillable).

How are Comics Made? Forever, apparently…

- Not that the book is otherwise vicious, you won’t find the point-scoring that appears ↩︎

- Another quibble – despite the rather wide-ranging name of the book, which appears to be discussing the field of comics as a whole, its text deals squarely with American newspaper comics strips. Not comic books, graphic novels, Japanese anthologies, Franco-Belgian albums, or any other format-dictates-content situations. Still, much of the process described in the book translates well enough to other realms of comics-making ↩︎

- Quote Dylan Horrocks in ye-olde The Comics Journal #234: “In one fell swoop [McCloud] has removed all other considerations – genre, style, publishing formats; in short, the whole embarrassing history of comics.” ↩︎

- My father is a photojournalist, I remember long hours in childhood spent in development shops or in travel to a printing house. I was bored out of my wits at the time, but now that he can do the same work with some clicks from home, I feel like something is lost. ↩︎

- David Foster Wallace, who didn’t live to see social media truly take off, was already fearful of the shattering of public consciousness. I am not as stark as he is — there are ups as well as downs, but the lonesome media-obsessed people of Infinite Jest, drowning in their own pleasure bubbles, seem to have hit the sport pretty well. ↩︎

- Compare the endless streaming libraries, I can’t tell you how many nights I spent being overwhelmed by options – it’s hard to choose when the options are near-infinite. ↩︎

- See also: the recent revival of the physical vinyl album format; or, to go a bit further back – the endless dirges sung for the physical book as an object for over a decade now, it’s still here! ↩︎

- Though I do wish the book were larger, many of the details are shrunk into Chris Ware-level minutia ↩︎

- Taken from David Carrier’s The Aesthetics of Comics ↩︎

- “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.” – Lewis Carroll. ↩︎

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply