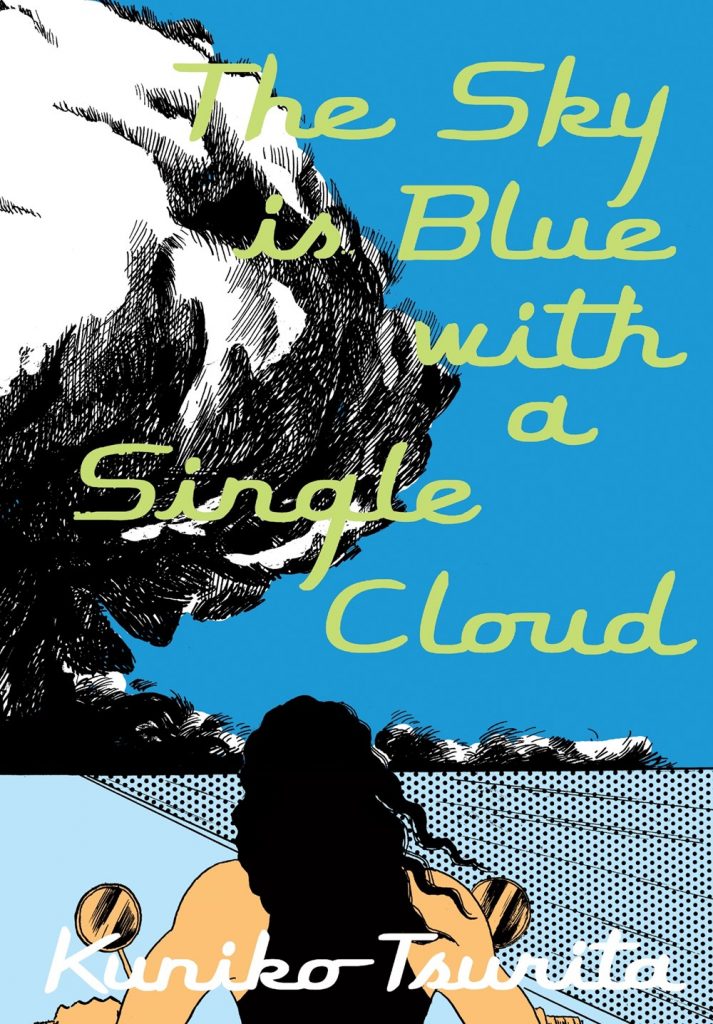

According to the compilers of The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud, Kuniko Tsurita, who died of lupus at the untimely age of thirty-seven, was possibly the first female cartoonist to produce alt-comics that were guided by her own creative and personal vision rather than commercial concerns or socially-sanctioned gender expectations. Graced with a thorough, informative afterword by Ryan Holmberg, The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud is a generous, well-annotated retrospective, serving as both a fitting memorial and effective showcase for this iconoclastic artist, the first and only regular female creator for the legendary alt-Manga magazine Garo.

The stories collected here were created between 1966 and 1981, and are presented chronologically for the most part. One of my favorite things about a single-artist anthology is seeing how successfully an artist evolves over time, their visual style morphing and maturing, their main themes coalescing into a singular vision or worldview. As evidenced here, Kuniko Tsurita began with skillful but unremarkable genre-based work, but continued to dig deeper, drawing more upon real-world events and personal concerns—among them the complications of gender roles—and channeling them into challengingly abstract stories crafted with innovative, often surreal cartooning. In the book’s second half, which features work she created while living with the terrible impact of Lupus, we see her full power as a creator come to fruition.

The collection kicks off with “Nonsense,” originally drawn in 1966, a tale of a young man who has made it his mission to murder evildoers: “Their lives are worthless. I will send them to hell, one by one!” Eventually, he is caught by authorities, receives a death sentence, and is executed. But the story continues on, showing us his fate in the Afterlife before concluding with a circular, meta ending. For young work, it’s pretty clever, featuring dynamic layouts and a keen sense of irony.

The book continues with several other genre-based stories such as the parable-like “Woman” and the dark, cynical “Anti,” both of which showcase Tsurita’s versatility in different story forms. But for me, things start to really percolate with “Sounds” (1969) and “65121320262719” (1970), which feel more personal and are laced with more urgency.

“Sounds” is a fantasy featuring a young woman who wakes up to find that she has suddenly become invisible. Even worse, an androgynous-looking young man has shown up in her bed, taking over, smugly dismissing her protestation: “But you don’t exist.” The newly-invisible protagonist retaliates by mercilessly nagging the interloper, eventually driving him away from her apartment. When she’s finally left alone, she feels driven to talk nonstop, to prevent herself from completely disappearing. Several days later, exhausted, she finally goes silent: “It was then, when I stopped talking, that I ceased to exist.” The last page shows the reader her empty apartment, the sound of a ticking clock all that remains. It’s a neat little metaphor, a cautionary comment on the perils of not claiming the right to one’s own space, and likely paralleling Tsurita’s situation with Garo and the constant threat of her work being belittled, stifled, or ignored in a man’s world.

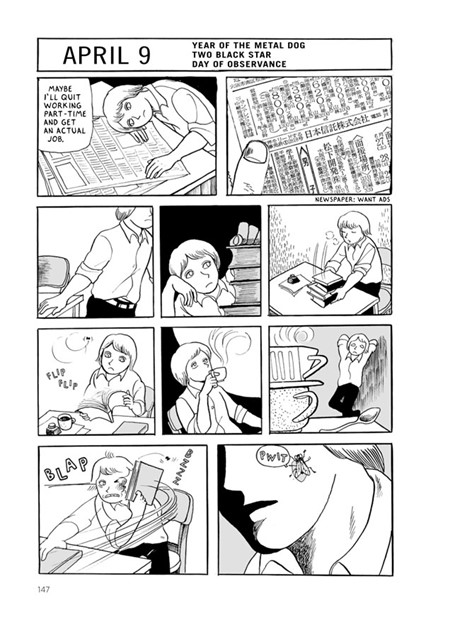

“65121320262719,” set against the student protests of the Vietnam War in the early-70s, relates to “Sounds” in that it features a young woman struggling against her traditionally passive female role. As Holmberg notes in the afterward, this piece was likely influenced by Tsurita’s own living situation at the time, along with her minority status at Garo. The story opens with the heroine letting her boyfriend hold a political-action meeting at her apartment. While the men gathered for the meeting passionately discuss issues, the host is ignored, so she eventually leaves to go grocery shopping. At another meeting, her role is limited to serving the men coffee. But when a policeman harasses her on the street, mistaking her for a student protestor, she fights back, kicking him before flees. “I did it!” she proudly exclaims, before admitting “But then I apologized.” Interestingly, the story concludes not with the heroine, who seems to be slowly groping towards fulfilling some personal goals; Tsurita instead pans away from her over to the increasing unrest on the streets, moving past her heroine’s concerns altogether, with the final panels suggesting violence in yet another clash between the police and protestors. It’s a refreshingly unexpected narrative choice, which I took almost as a warning that to not engage in pressing social problems of the day means the world will simply pass you by. The parallels to our situation here in 2020 with the Black Lives Matter movement and other social justice issues are painfully obvious.

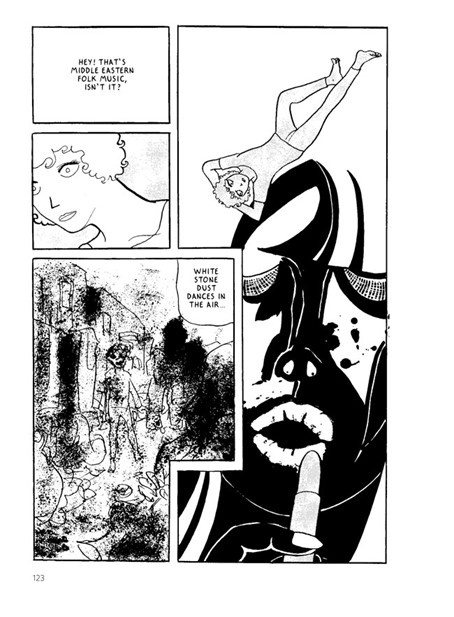

In other selections, which focus on troubled romantic relationships, such as “Occupants,” Tsurita’s art and storylines go out into the ether, highlighting mood over plot and employing stylized and/or experimental visuals, fully embracing non-traditional storytelling. Several of these stories feature female-female relationships, though Tsurita was not queer or queer-identifed (“girl love” being its own genre in Manga). “Occupants,” is an essentially plotless look at the contentious relationship between two women: one a boyish, short-haired blonde, and the other a long-haired siren whose face Tsurita always renders in silhouette, lacking any features except a lavishly-lipsticked mouth. Here Tsurita’s drawings have an appealingly cruder, underground-comics feel, reminiscent in places of Rory Hayes (I have no evidence that she was at all influenced by Hayes but that’s what it looks like to me). It’s also flat-out weird, featuring all sorts of psychedelic and celestial imagery, and deliberately lacking any traditional story arc.

Another odd, cryptic view of a female-on-female relationship is “Max,” narrated by the title character in a free-associative style. This piece, drawn in 1975, is much more sophisticated than the likably self-conscious psychedelics of “Occupants,” opting instead for a cool, Goth sheen, and an eerie atmosphere of decadence and malevolence, drawn in spidery lines enhanced with intricate patterning. Max, a long-haired, black-clad woman, shares memories and contemplations in a desultory manner. She recalls witnessing a trio of ghoulish figures gleefully pouncing on a young man one night and throwing him into the river (“like garbage”), and converses with another woman, her lover, who seems to both encourage and antagonize her. The narrative is so fluid and open to interpretation that at one point I wondered whether the other woman even existed, perhaps representing Max’s id. Towards the end, Max begins to talk of her mortality: “When I die even my friends will forget that I even existed. I will simply disappear.”

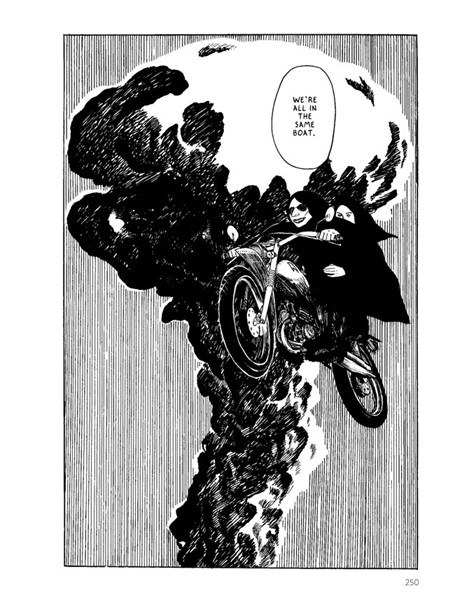

The inevitability of death becomes the thread that ties the second half of the collection together. According to Holmberg, Tsurita drew the pivotal “My Wife is an Acrobat” after receiving her diagnosis of Lupus, which devastatingly altered the remainder of her life. “Acrobat” features a man (a stand-in for Tsurita’s husband, according to Holmberg) peering voyeuristically at a nude woman (Tsurita) bending and stretching alluringly for him. Mid-story, he is depicted alone, trying to balance on a ball, metaphorically balancing his separation from her. Eventually, the woman deteriorates from being young and healthy (and very bendy) to slumping defeatedly in a full bathtub. She concludes remarking that she is now “dead and pickled in alcohol.”

In what I think of as the story’s companion piece, “Yuko’s Days,” set in a bleak medical facility, the protagonist is overwhelmed by the illness and death all around her while overhearing her doctors discuss “Lupus Erythematosus…gamma globulun…white blood cells.” She confesses to escaping to the roof of the facility whenever possible, to gaze out at the mountains and cityscape below, imagining “people chatting happily.” In both tales, Tsurita unflinchingly describes the isolating effects of chronic illness, perhaps as a form of self-therapy or catharsis, yet channeled through her poetic imagination.

In the final quartet of stories, Tsurita returns to the realm of fantasy fiction, each of which features characters grappling to achieve a sort of transcendence through beauty, though all with fatal consequences. First is “Arctic Cold,” which describes a dreadful frozen dystopian world and a man willing to risk everything for the love of his doll-like wife. In the lovely, fable-like “The Sea Snake and the Big Dipper,” a mermaid-like creature breaks the ocean’s surface for the very first time and becomes transfixed by the sight of the distant stars in the sky. Though her obsession with their magnificence eventually leads to her demise, she dies happily as she stares up at them, transfixed.

In the brief “R,” the title character, a beautiful young woman who was rescued as a baby and raised by an apparently female wizard, becomes a terrible nuisance as she matures. This forces the wizard to cast her out, replacing her with a new and improved version of R. “Who exactly was R?” the narrator asks in conclusion. “Did she eventually disappear as a drop in the ocean?” I’m thinking that in Tsurita’s fanciful universe this conjecture is borne of hope more than anything else; a refusal to consider either the pain of life or the finality of death as endpoints.

Finally there’s “Flight,” in which a man with a deep passion for flying planes is killed while navigating his aircraft through a terrible storm. A few years later, his paramour, a young woman who has struggled to accept his death, discovers something unusual about him while on a trip to Egypt. It’s a beautiful little piece which once again hopes that death is not the end, that perhaps there exists a larger purpose for us in the scheme of things.

As Tsurita’s illness ground her down and her energies dwindled, perhaps this notion brought her the strength to face her demise—and whatever awaited afterward. It certainly brings this posthumous collection to a satisfying, if bittersweet conclusion. Though Tsurita trafficked in multiple genres and employed any number of artistic styles, her work had scope and poetry—and she gave it all she had to give. Though, perhaps, in the end, her most urgent theme was death itself, she examined it and transformed the dreaded subject into something ultimately life-affirming. The book feels of a piece, a tribute to an artist many of us had never known of previously, but can now honor.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply