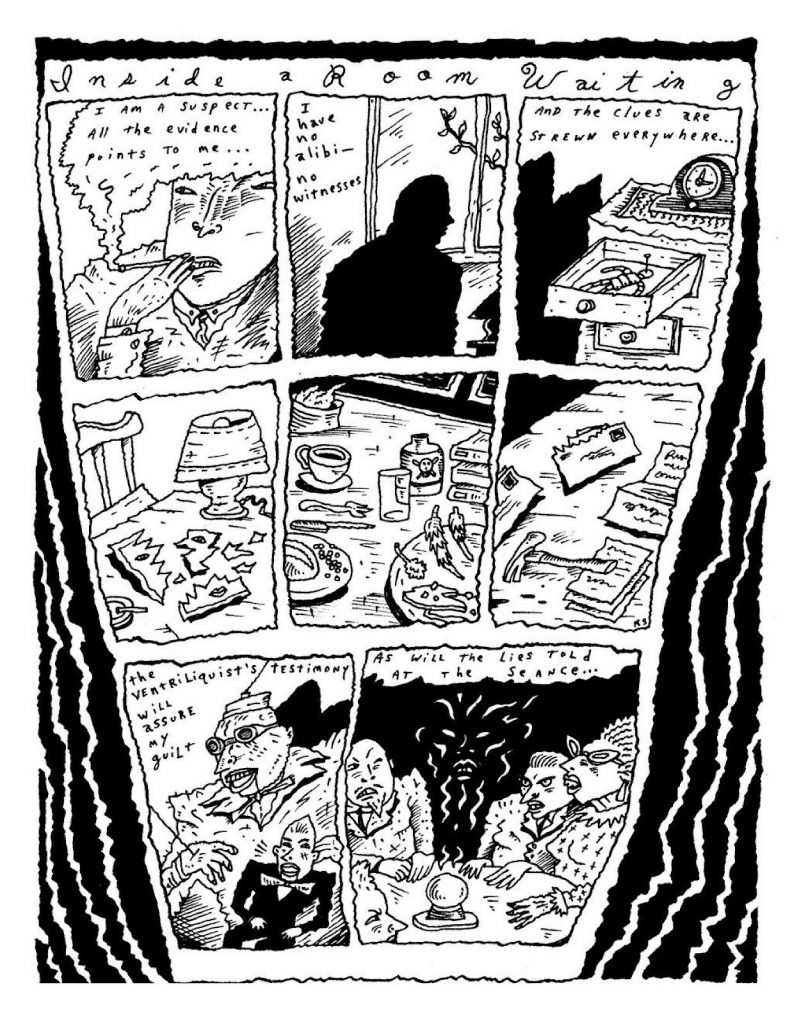

I keep trying to think I’m someone else, narrates the man, but I’m always myself. A woman has been murdered; the man is sitting around and waiting to be captured. Yet whether or not our protagonist actually did the deed is open to at least some interpretation: on the one hand, he acknowledges the evidence against him, his lack of an alibi, and the mark of the guilty (a knife and fork) branded on his forehead; at the same time, however, he cites the “the ventriliquist’s [sic] testimony” and “the lies told at the séance” — methods of investigation that are both absurd and, in the specific idiom of his author, perfectly in place. Either way, the guilt in practice is entirely beside the point, as he is entirely resigned to his fate: even if his actual execution has yet to take place, he’s already a dead man.

The above story, the two-page “Inside a Room Waiting,” is one of the more dramatically-straightforward showings in Night Drive, the self-published debut of Richard Sala, reprinted by Fantagraphics — in a somewhat modified form — this past May. It is also, by some distance, my favorite piece of the bunch, a perfect encapsulation of an emotional space of despair-beyond-despair: even in one’s imagination, one cannot escape one’s fate. In his memoir The Discomfort Zone, Jonathan Franzen writes about his experience reading Kafka’s The Trial in college and becoming violently aware that, although the novel’s famous opening line embodies one ‘universe of interpretation’ which many take for granted (the conventional assumption that K. is innocent, dogged by the panopticon of totalitarian bureaucracy), the text’s descriptions of K.’s actions in practice imply quite another narrative — that he is in fact guilty and deserving of punishment, and has been lying to himself to evade self-examination, only to now have that examination foisted from the outside. Sala’s “Inside a Room Waiting” operates in a manner quite similar to Franzen’s view of Kafka, only with one key difference: Sala’s protagonist, whether guilty in the legal sense or culpable in the broader societal sense, won’t even bother with the pretense of fighting for his good name. He will simply sit inside a room and wait.

As I have written, in some form or another, in the past, engaging with archival reprints of early works by established artists, certainly posthumous editions, generally requires a certain degree of voluntary cognitive dissonance; as the reader is forced to bear in mind the artist’s subsequent standing, the work itself is warped by context, both diegetic (in the form of the introductions, prefaces, forewords, and other supplementary materials usually included in such editions) and exegetic (in the obligatory mental scouring for connections to later works, connections which, fundamentally, emerge only in retrospect).

The Fantagraphics edition of Night Drive — the first such reprint since the original release — revels in this cognitive dissonance. To start with, readers are reminded several times that Sala himself came to distance himself from the book, perceiving it as the embodiment of his indecision between sincerity and ironic detachment, which he ascribed to his background in fine art; much of his subsequent entrenchment in genre stories was a refutation of that earlier ‘artsiness.’

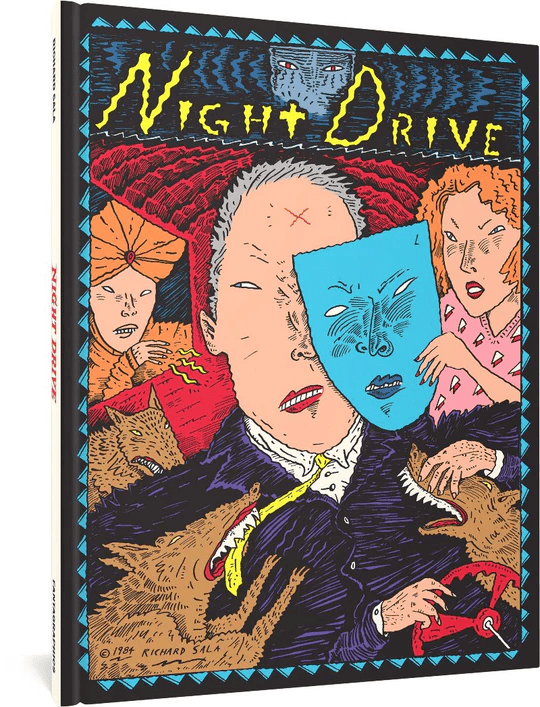

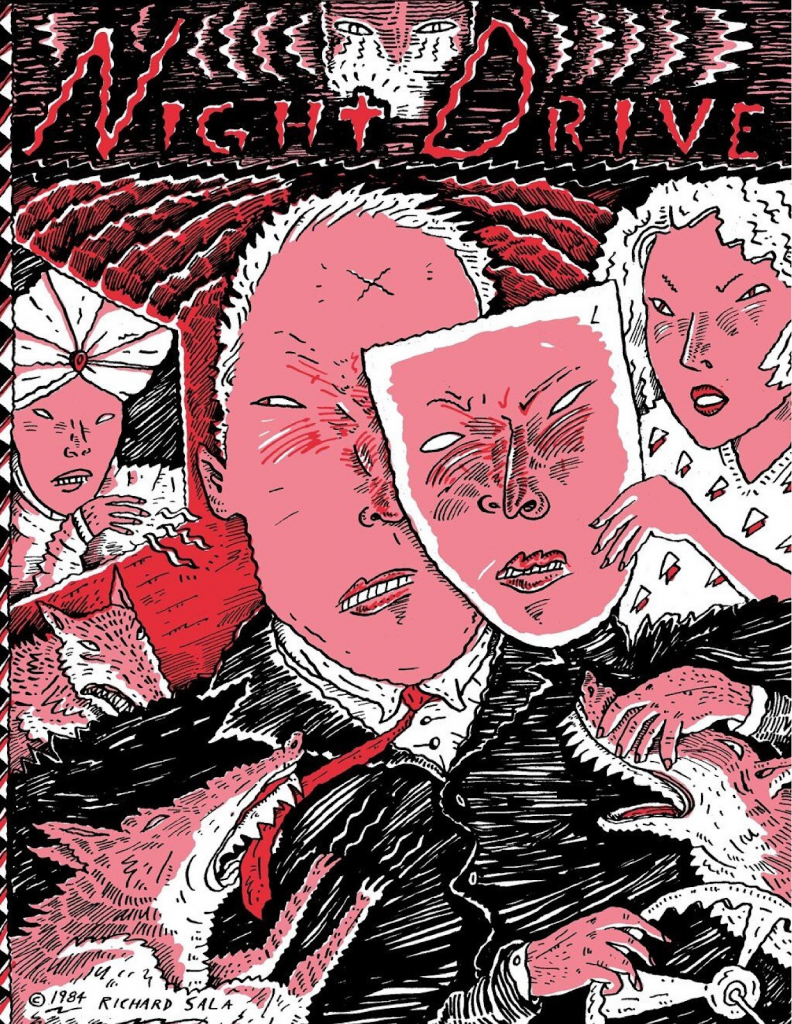

Furthermore, its production is a far cry from the comic’s original form. Originally a saddle-stitched 32-page one-shot, it is now a lavish hardcover with double the page count; the cover to the reprint is in full color, in contrast to the cover of the original release, which featured only black ink and hues of red. The inner front cover is a black-and-white photograph of Sala, who died in 2020, while the back endpapers are a collage of frames from the animated adaptation of the Night Drive short “Invisible Hands,” broadcast as part of MTV’s Liquid Television. The added pages include a remembrance of Sala by friend and collaborator (and editor of the present edition) Dana Marie Andra; excerpts from interviews and from Sala’s Tumblr that touch on the book and the animated adaptation; and an afterword by Daniel Clowes, another close friend of Sala’s and the designer of this reissue. Even the title Night Drive is not entirely apt, as, in addition to the 1984 release, other early comics are collected as well — 1988’s “Behind a Door,” written by Andra for her Fantagraphics anthology Street Music, and a handful of odds and ends either excluded from the original Night Drive or meant for a never-completed follow-up.

None of these changes, I might stress, are detrimental; they simply change the nature of the Fantagraphics release from a mere facsimile to a view of a broader moment in authorial time — the ‘second birth’ of Richard Sala. I say ‘second birth’ because the comics herein are not, strictly speaking, Sala’s first; for even earlier work, readers are advised to seek out issue #10 of Fantagraphics’ present flagship anthology Now, which compiled five very short comics by Sala. These, however, were couched in a crucial caveat from editor Eric Reynolds: “There is every reason to believe that Sala would not have wanted these pages to see print. He had never shared them with friends.” And, indeed, at first glance, the cartooning is not recognizably Sala’s — the lumpy figure work is closer to pulp-remixer Eric Haven, while the pooling thickness of the ink evokes, perhaps, Noel Freibert, or, more conservatively, Troy Nixey.

Night Drive, then, may not be the cartoonist’s definitive ‘first,’ but it is nonetheless the marked starting point of Richard Sala in his familiar style. From this point on, his rendering might change — compare, if you will, the inky woodcut-like grooves and stark black-and-white of The Bloody Cardinal to the smooth brush-strokes and warm watercolors of Violenzia — but underneath the work would remain the same: the flattened depth-of-field; the characters’ sharp, pointy features and rigid poses; and, more than anything, those perpetual squints, like no emotion exists in the world other than suspicion and distrust.

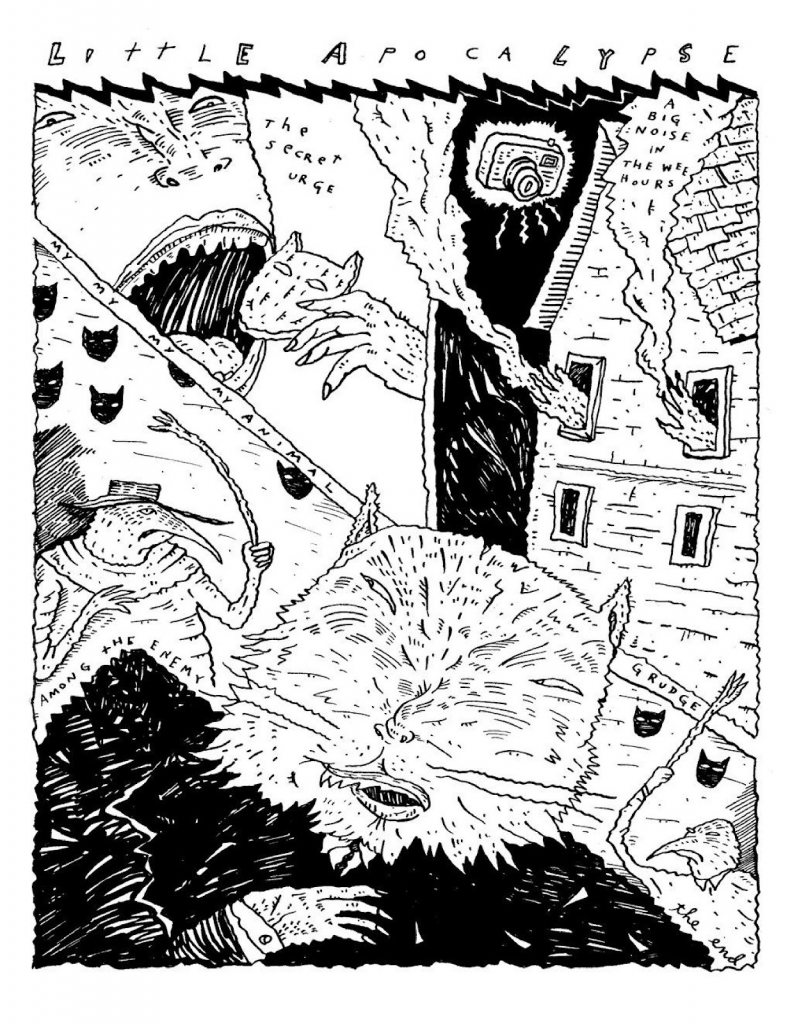

In more ways than one, Night Drive is a dizzying piece of work: on the structural level, its thirty-two pages contain a whopping fourteen comics, most of them being one or two pages long (“Invisible Hands” is by far the longest, its two parts spanning seven pages); on the formal level, many of these comics are loose, disjointed works, usually skewing more toward the atmospheric than the conventionally narrative. This is particularly true for the smattering of one-pagers: works like “Curiosity,” in which a crowd looks through a broken window at a forbidden plant (the plant being an image that recurs several times throughout the book), or “Possession,” in which a man with a saw skulks around a nameless town, eschew conventional panel grids and rely on extradiegetic narration (the prevailing mode in Night Drive — only two of its fourteen comics employ direct dialogue in word balloons); other pieces like “Little Apocalypse” are formally more sedate — three clearly-delineated panels that indicate a clear chronological sequence — but their narratives remain bare-bones. In the ‘art world’ milieu toward which these pieces were geared, the natural comparison is Raymond Pettibon: a formal approach clearly informed by comics but so distilled as to approach the monumental.

Much like Pettibon’s work, the tonal landscape of Night Drive is one of anguish; its protagonists — typically male, typically without distinguishing features, a backstory, or even a name — are fidgety and distracted, and, more often than not, guilty, whether the culpability is established in fact or merely perceived. Note his recurring choice of protagonist: “Inside a Room Waiting” has its man-awaiting-punishment; “Little Apocalypse” portrays its protagonist, implicitly, as a predator, a man driven by “my my my my animal grudge” who eats a cookie that transforms him into a cat to combat anthropomorphic birds who only have sticks (or perhaps they are the talons of other birds long dead) to defend themselves with, whereas the hero of “Voice of the Dog” is a werewolf whose television sends him on destructive rampage. Again and again, havoc is coupled with the first-person perspective of the tormented soul that wrought it.

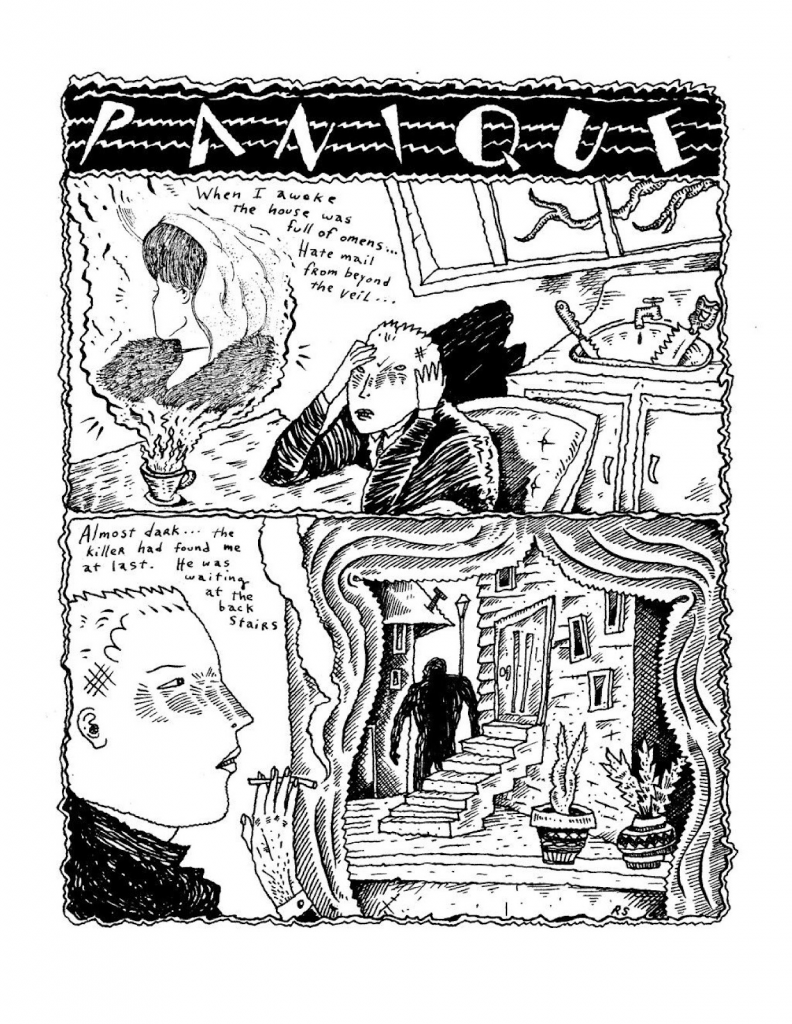

The three-page “Panique” follows a similar pattern: the protagonist is tormented first by the spectral visage of a dead woman, then by the arrival of a killer dressed, Invisible Man-like, in bandages and goggles. The protagonist doesn’t seem to have much of an inner life (the killer finally catches up to him while he works on a jigsaw puzzle), leaving the brunt of the narrative’s ‘meaning’ to form in the way of inference, the duality of the hauntings — the woman’s appearance, described as “hate mail from beyond the veil,” and the killer, dismissed as a mirage for he could not have survived “that last ‘accident’” — implying not a mere random supernatural occurrence but rather an EC-esque conceit: justice is never denied, only deferred.

“Panique” seizes one’s attention immediately, on the very first panel. Note the way Sala draws the spectral vision of the dead woman: for the book’s sole stylistic-textural divergence, Sala uses a much thinner pen, and his jagged line is exchanged for smooth, round strokes. Few distinguishing details are offered, as she faces away from the reader, but the texture is enough to evoke a ‘50s conception of elegance. Coming from a stylist as distinct and as relentless as Sala, this appears a pointed, intentful choice: the only element of ‘conventional’ beauty now gone, banished “beyond the veil” and replaced with Sala’s idiosyncratic tremors.

Occasionally I return, in my thoughts, to my friend and fellow critic Tom Shapira’s review of Jack Cole’s humor strip Betsy and Me. Cut short by Cole’s suicide, the strip has come, perhaps inevitably, to signify something greater than itself; the words ‘final work’ tend to take on capital Fs and Ws under such circumstances, as intrepid critics — in this case the esteemed likes of R.C. Harvey, Art Spiegelman, and Ron Goulart — rush not to separate art from artist but rather to entrench the connection between the two, looking for signs where such might not, strictly speaking, exist. “To narrow it all to the point of personal tragedy, a reflection of the artist in his darkest moment, is, to me, to miss the forest for trees,” writes Shapira. “Jack Cole committed suicide, but that’s not the only thing he did and that’s not the sole measure of his life.” It’s a handy reminder — the practice of criticism is a pursuit of sense-making, and, in search of explanation, it is easy, sometimes, to lose sight of the difference between stepping and overstepping.

In this regard, Night Drive proves somewhat trickier, thanks to the cartoonist’s own comments. In a 1998 interview for The Comics Journal conducted by Darcy Sullivan, Sala said of his comics, “What I’m writing are fever dreams. One person thrashing about in a world he doesn’t understand. Don’t bother searching for anything resembling a fully-rounded character.” At the same time, he described them as “basically extensions of my own personality. People used to ask me, ‘Why don’t you do autobiographical comics?’ And I would say, ‘I’ve been doing them. These are my autobiographies.’” Sala, who struggled with active suicidal ideation throughout his teenage years and his twenties, “never thought [he] would make it to 30”; Night Drive was made when he was 29.

This, of course, creates something of a dilemma — on one hand, where Sala cites the influences most palpable in Night Drive (Kafka, Mark Beyer), it is precisely on that same emotional level of self-alienation and hopelessness that they spoke to him; on the other hand, to inspect Night Drive solely through this prism would be not to take Sala at his word so much as to flatten him and his word, a reduction that neglects to take into account the role of the artist as an aesthete rather than a mere therapeutic confessor. This appears doubly unfair in the case of Sala, the key function of whose aesthetic is distortion to the point of semiotic annihilation. Consider, for example, the tools of investigation in “Inside a Room Waiting”: parallels may be drawn between the act of interrogation and ventriloquism, in that both focus on ‘prompting the reticent to speak,’ or between a séance and an autopsy, which focus on the victim’s ‘testimony’ but such parallels are overridden by the implications of Sala’s chosen signifiers. And this is, in fact, where Night Drive excels: in its employment of emotional distress — whether confessional in nature or more generalized — not as a means to its own end but as the starting point to the aesthetic process.

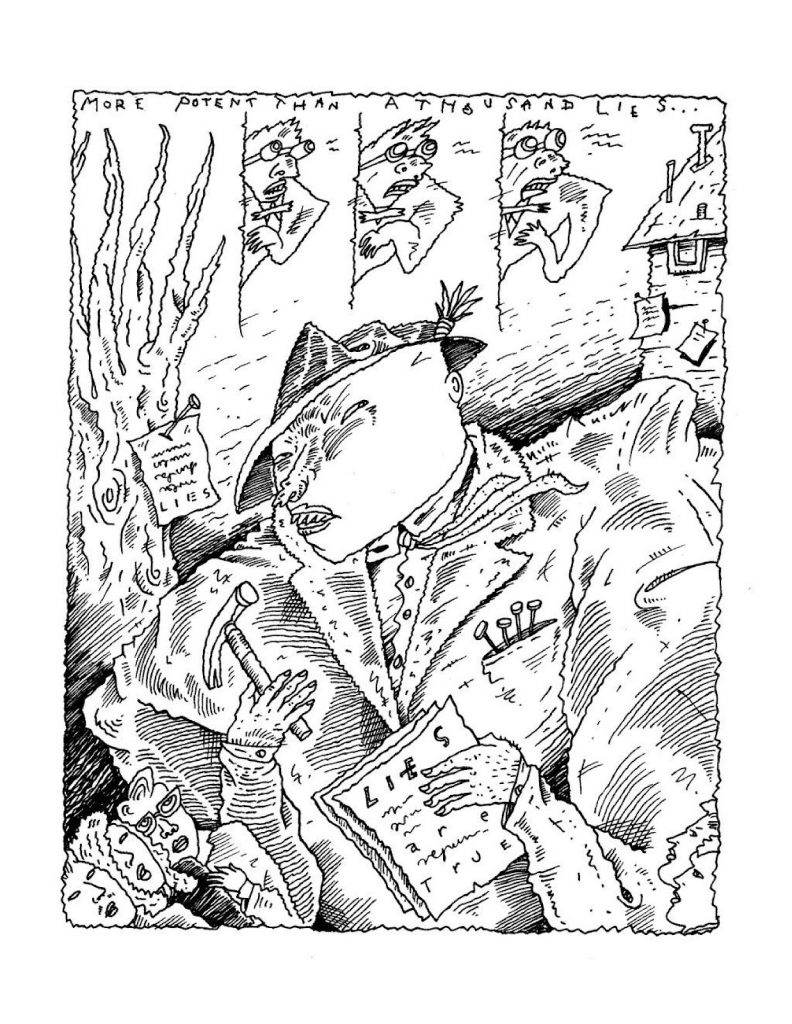

We may look, for instance, at “Fatal Word,” which in spite of its relative length, retains the fragmentary structure of the one-pagers, operating more like a poem than a story. Structurally, each of the piece’s four pages is a single image; the first three pages sport a line of narration, while the fourth page breaks the pattern by pivoting into direct dialogue. What’s interesting about “Fatal Word” is that the tie between the verbal and the visual is a tie of simultaneous contradiction and complement. On one hand, the verbal component is simple: first the narration — “fatal word / when spoken / more potent than a thousand lies” — then the ‘reveal’ that the ‘fatal word’ itself is merely a woman’s “no” to a man. Yet the visual lead-up to that “no” — a story of always-look-over-your-shoulders-paranoia — turns the ending almost into a non sequitur. Note the construction of the third page:

On the one hand, there is the composition, which clearly borrows from woodcut artists like Ward or Masereel in its eschewing of naturalist perspective; as the ‘mystery man’ pins dramatic notices around town, he becomes the center of dramatic gravity: the townspeople not only looking up at him but also shrunken by his presence. Yet, on the other hand, we have the actual phrasing of his notices: LIES ARE TRUE — almost childish in its articulation, histrionic, hard to take seriously. In following this with the image of a man’s advances being rejected (the word balloon of the woman’s “no” jamming like a spike into his heart), Sala recognizes the outsize emotional impact of the rejection, at the same time seeming to say, And isn’t that just a little bit ridiculous?

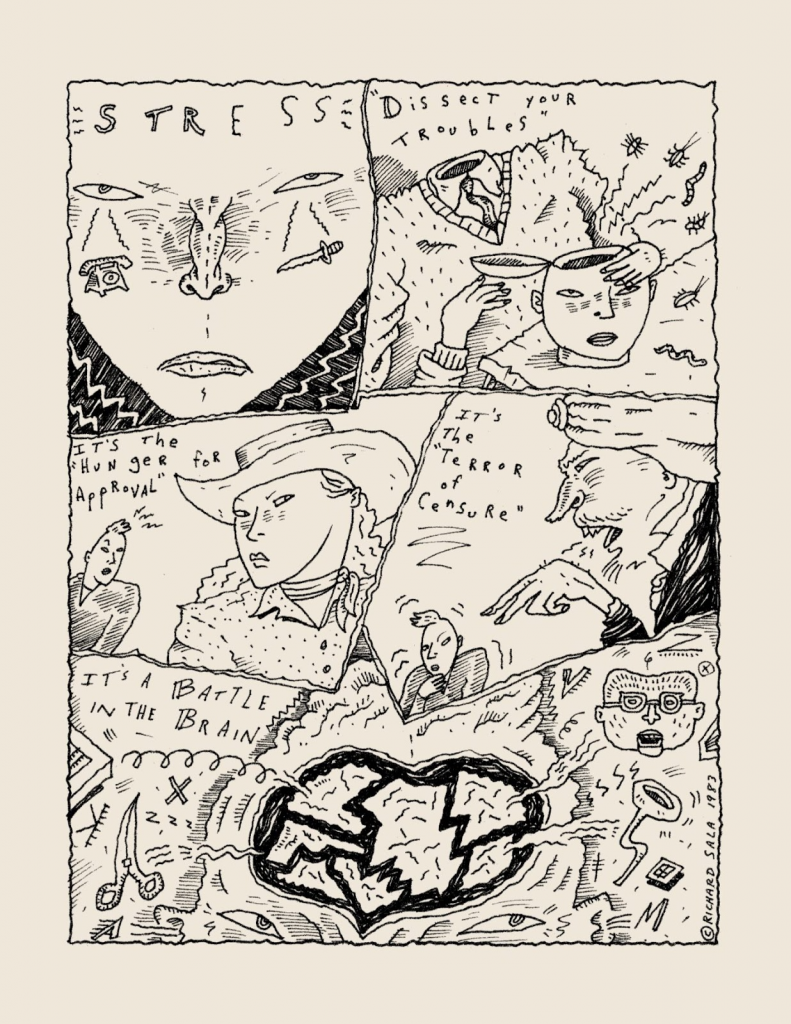

Such wry dismissals abound in particular in the book’s outtakes section: “Stress” displays a “battle in the brain,” inviting one to “dissect your troubles” while not offering any way out of them; an untitled drawing shows a therapist torturing a patient while repeatedly writing the phrase “You are okay” in his notepad, prompting the patient to repeat, almost as a chant, “I am okay, I am okay, I am okay” while his head is physically being sawed open. The one-page outtake “Jealousy” can be read in two different ways. The first six of its seven panels are disjointed vignettes, each representing a different emotion: for suspicion, a man looks back over his shoulder while shadows loom on the wall beside him; for obsession, a man grips his head, distraught, while looking up at the spectral visage of a woman. These feelings escalate and overwhelm — until the last panel cuts away to a man watching television, with the narration: Just another dumb story / night after night. On the one hand, the detail of the television may be taken at face value, commenting on the ‘trash media’ that Sala himself loved for both its formulaics and its histrionics; alternately, it can be taken as another bemusedly-dismissive look at the emotional misery that dominated the works of his peers (and which would intensify over the next decade). Either way, the prevailing tone is a wry knowing wink, a self-distancing flick of the wrist: Ah, don’t take it all so serious-like.

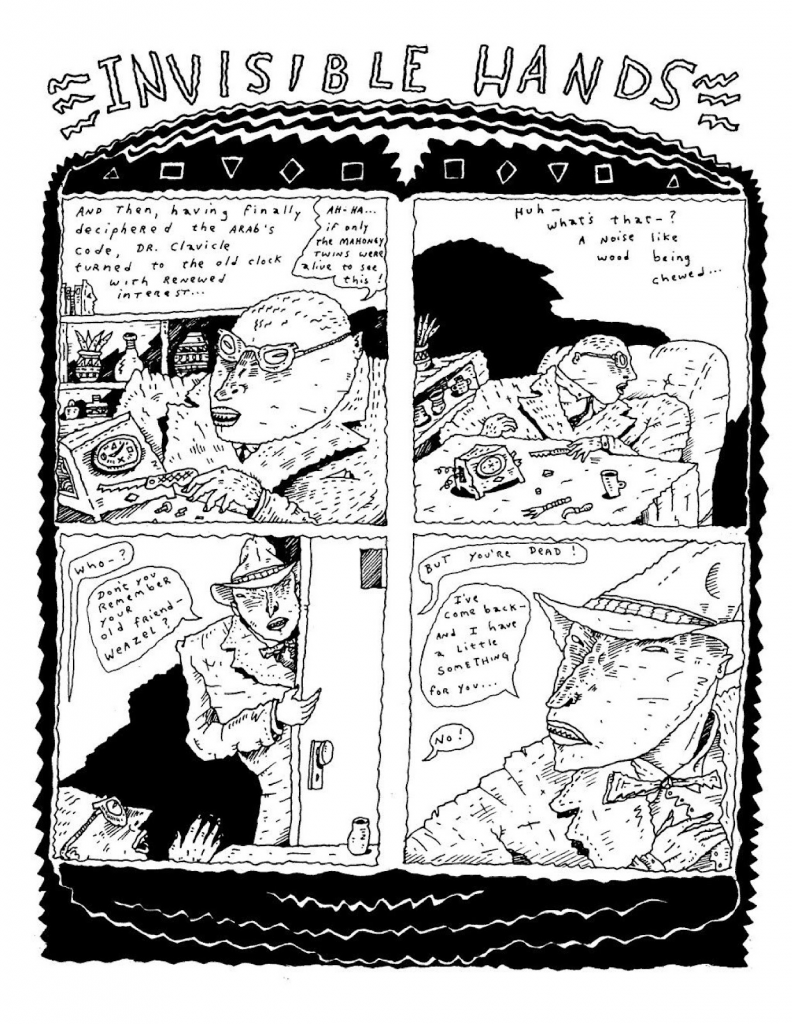

“Invisible Hands” — arguably the centerpiece of Night Drive simply by dint of its length — sees the convergence of two objects of Sala’s fascination: the unwavering reliance of pulp authors such as Walter Gibson or Ian Fleming on hyperspecific structural formulas, alongside the poet André Breton’s habit of going from one movie theater to the other and only watching snippets of movies in succession, never completing a movie from start to finish. Note the total opposition between the two: in the pulp vision, the author exerts complete control over the story by reducing it to mathematics; in the French Surrealist vision, the reader seizes control by choosing when the work begins and ends, regardless of authorial intent.

In trying to reconcile the two approaches, what Sala ends up with is in essence a farce: with a clipped, frantic pace evocative of Mark Beyer — scenes end abruptly and cut away sometimes twice within the same page — he reduces his plot to the sum of its archetypal tropes (betrayal, resurrection, mistaken identity), and watches on as they lose their forcefulness through mere attrition; the characters have little personality beyond plot function, and, as unresolved questions mount, the reader is given no reason to believe that this procession of schlock will ever cease to drone on.

Sala himself was ambivalent about the piece and almost omitted it from the 1984 release because of what he perceived as its incongruence among the other comics; compared with the more ‘arty’ pieces, the two-parter “was not meant to be taken seriously.” It’s not hard to see some truth in the description — in many ways, the ironic detachment Sala would come to deride is at its most palpable here — but such a description inevitably winds up selling the comic short; a sharp exercise of criticism-in-practice, it is arguably the book’s most energetic piece, and certainly the one whose objective is most clearly stated.

“The solution to the mystery is always inferior to the mystery itself,” wrote Borges in “Ibn-Hakam al-Bokhari, Murdered in His Labyrinth” — a quote that appears as the comic’s epigraph. It’s an apt choice, to be sure — not for the last time, in Night Drive Richard Sala reveled in a world with little hope for a tidy resolution, and despite the cartoonist’s harsh self-criticism, it stands as a work entirely undiminished by the corpus that followed it. In 2025, as in 1984, it is vivid proof that Richard Sala did not need to think that he was anyone else: he always was himself. For that, we should be thankful.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply