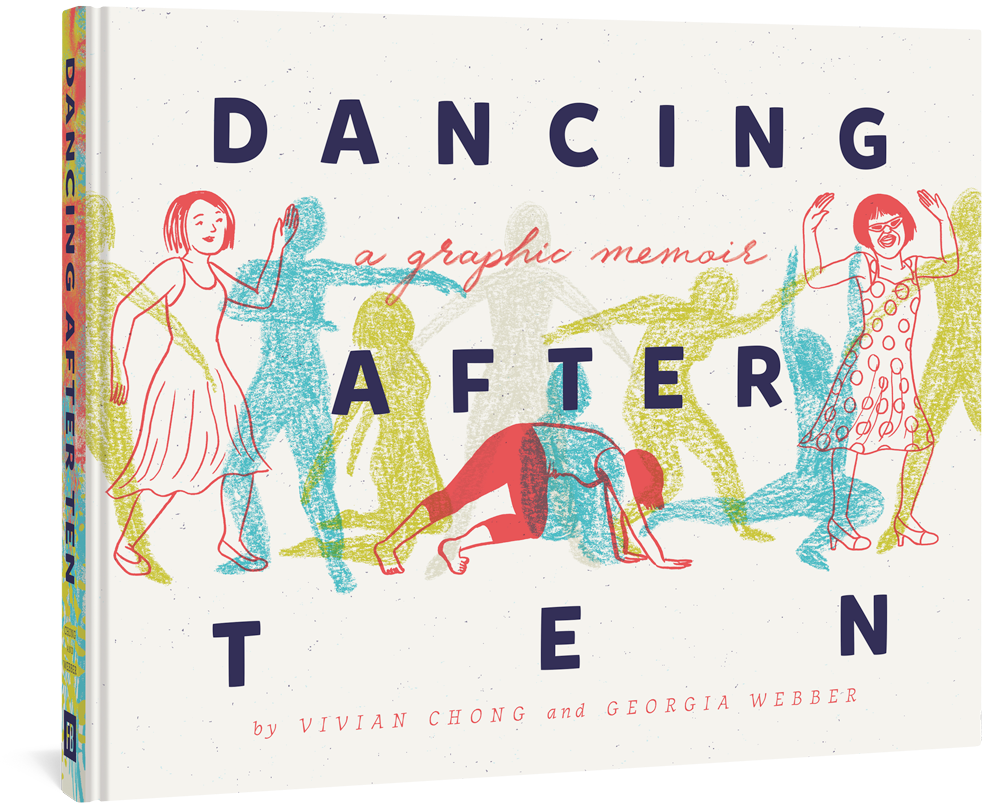

Just to get one item of “housekeeping” out of the way at the outset: the TEN in Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber’s new graphic memoir Dancing After TEN (Fantagraphics, 2020) is capitalized deliberately as it refers not to the number, but to a rare skin disorder called Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis which Chong developed on vacation in St. Martin with her ex-boyfriend and his family in reaction to a prescription medication she was taking. That, however, was only the beginning — in due course she found herself temporarily comatose, subjected to a lengthy (and frankly humiliating) series of largely-ineffective medical treatments, and left with scar tissue that caused drastic visual (and, later, hearing) impairment. All of which leads to two questions: how did she make it through all this, and how did she end up doing a comic about it?

Taking them in reverse order, the answer to the latter question is: with a great deal of help from the perfect collaborative partner, Georgia Webber, whose own memoir, Dumb: Living Without A Voice chronicled her struggles with precisely what its title implies with a kind of disarming candor and raw emotional authenticity. Her delicate and expressive illustration of Chong’s story strikes precisely the right tone throughout, whether she’s delineating triumph, tragedy, or all those many points in between. Her challenges inform her artwork, absolutely, but she never allows them to leap to the forefront, opting instead to draw from them the perspective she needs to visually translate Chong’s words from a place of understanding rather than mere sympathy.

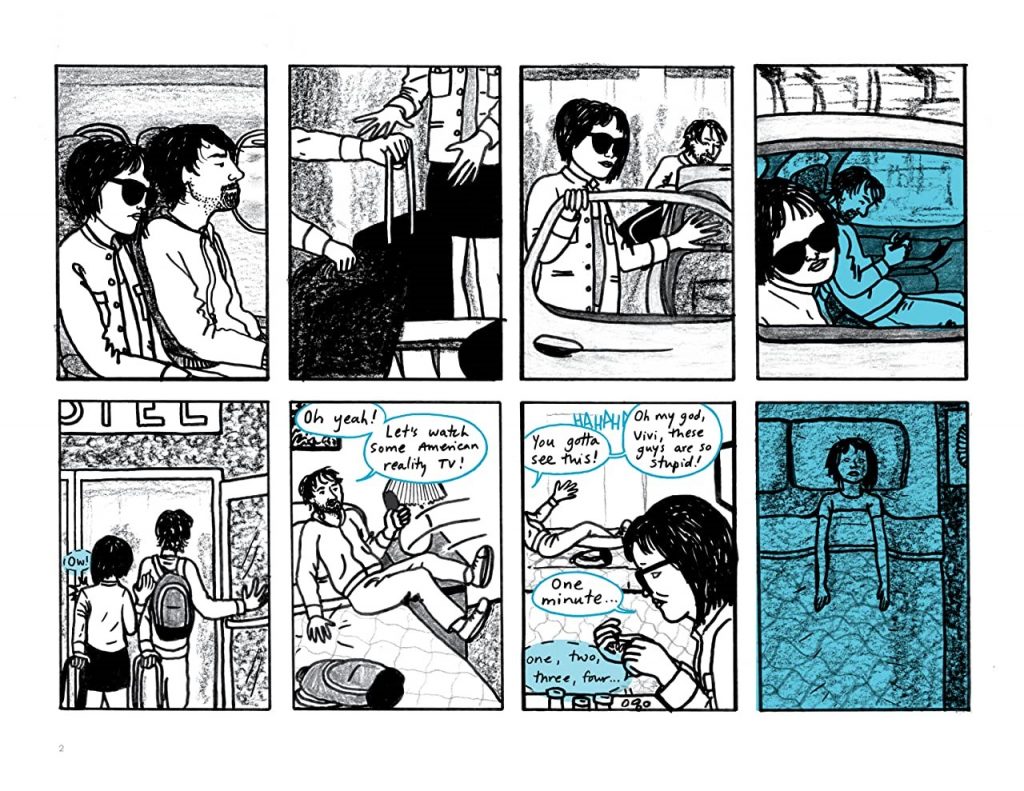

Now, as for our first question — how did Chong make it through all this? — well, that’s what this book is all about, and, as with all tales of struggle and survival, it’s a harrowing journey with numerous highs and lows. I don’t wish to give away too much by way of specifics, but it’s probably not too major a “spoiler” to reveal that Chong begins to find her way out of the metaphorical darkness by means of creative self-expression, experimenting with dance, singing, drumming, stand-up comedy, and even running before surgery temporarily restores much of her sight, at which point she literally throws herself into her creative endeavors even more zealously, including sketching out the bare-bones pages that Webber ended up finishing — as well as accentuating with well-placed teal shading — for this memoir.

As it happens, though, comics is only one medium via which Chong has chosen to tell her story, the other being Dancing With The Universe, a dance-theater production staged in Toronto that functions as a companion piece to this very book and was similarly largely conceived during the period Chong’s sight was partially restored. If you’re getting the impression she’s a person who’s determined to make the most out of the time she has, you’re absolutely right.

That being said, while she details the events of her life with remarkable clarity, her take on her own interpersonal relationships is a bit more distant and sometimes fails to strike a chord. In and of itself, this isn’t that huge a problem early on, but as she travels the road to emotional wellness and leans more heavily into her “freedom in forgiveness” thesis, there’s less for the reader to really empathize with, especially when contrasted with the much stronger dual-track “freedom through creative expression” narrative. I have no doubt that emotional wellness is predicated upon forgiveness, and that it takes guts to follow through on, but the jump from her ex, Seth, being a self-centered asshat who dumps her like a hot potato the minute she’s admitted to the hospital to her forgiving him as part of a group role-playing exercise is wide gulf traveled without many stops between. It doesn’t help matters either that he still comes off as a self-absorbed prick and that Chong’s partner at the time she’s stricken with TEN (and as events progress), Micheal, doesn’t necessarily seem too much better himself.

Still, given that the overall trajectory of this narrative is focused on the act of becoming through healing, the secondary plotlines revolving around Chong’s relationship choices are certainly “of a piece” with the work as a whole. However, her commitment to creative exploration as a means toward the same end lands with much more impact and frankly seems to be where her passion lies.

As a therapeutic exercise, then, it might be fair to say that Chong’s memoir certainly does what it needs to do for its subject/author, and likely for her artistic collaborator, but readers aren’t necessarily brought along for the ride as thoroughly in some respects as they are in others. That doesn’t necessarily minimize the ultimate impact of the work itself, but it does muddy the waters a bit along the way. Where the project ultimately redeems itself, however, is in proving its central thesis that creativity is therapy. The term “graphic medicine” has been gaining currency in the comics community in recent years, but here it’s taken to its literal extreme, with the creation of the comic itself being part of the author’s healing process.

Looked at through that lens, my minor quibbles with it seem just that — minor. And I suppose they are, but given the sheer amount of heart and effort that went into Dancing After TEN, to give it anything less than a thorough-going analysis would be less than Chong and Webber deserve. And while I’m certainly no doctor, I have no qualms in prescribing this to anyone who’s either been through a traumatic and life-altering medical experience, or who simply wants to learn about what it takes not only to survive one, but to thrive afterward.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply