In The R.Crumb Handbook, Robert Crumb is quoted as saying:

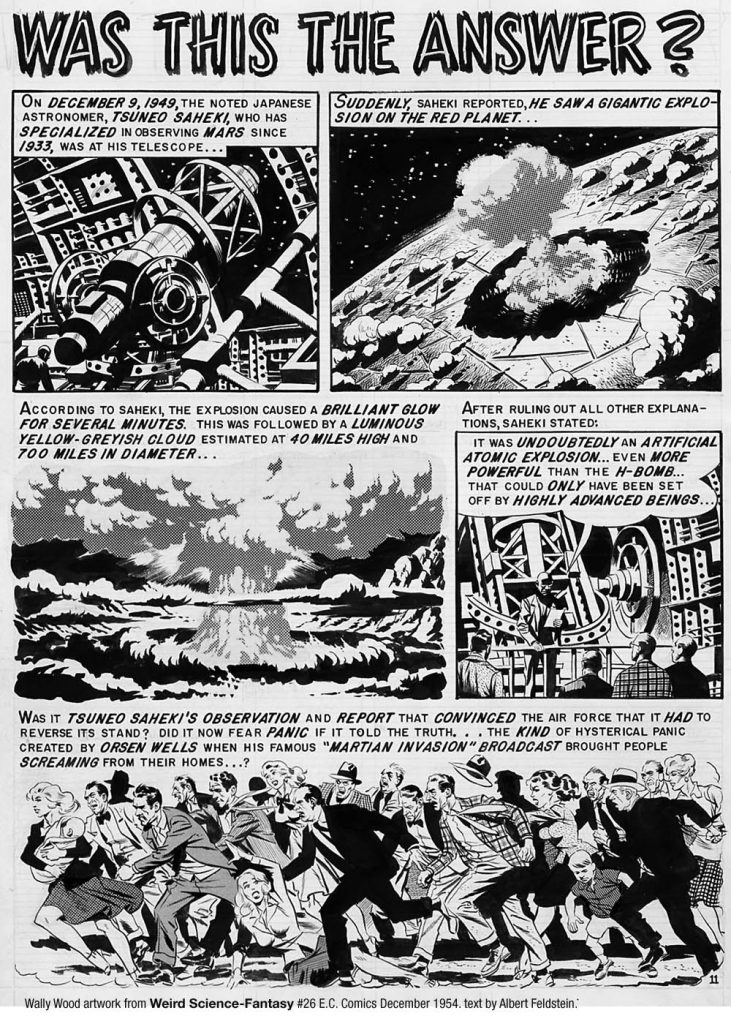

“If you look at a comics page drawn by Jack Davis or at Wally Wood’s science fiction stuff, who cares about the narrative? But the artwork is wonderful, a true pleasure to the eye. What technique! With Charles Schulz or Jules Feiffer, it’s quite the opposite. The story’s great, but the artwork’s not much to look at. In comics there’s always this dichotomy.”

There’s also an apocryphal quote from Wood saying that if he had to do it all over again, he’d draw like Schulz. In other words, he’d pick a less labor-intensive, “easy” style.

This is a false dichotomy. It’s a dichotomy that’s at the heart of the relationship between illustration and cartooning. It conflates naturalism and detail with “technique.” Illustration, by its nature, is meant to convey a single, static image. It’s usually done with work-for-hire specifications in order to sell someone else’s idea or product. It’s no wonder that technique and naturalism are important considerations for illustrations because it’s aimed at a wide audience.

Cartooning is a related art form, but one with important differences. Most cartooning is sequential in nature. Even single-panel cartoons can emphasize things like bodies interacting in space, the passage of time, gestures, etc. There’s a fluid, forward motion in cartooning, even in its more abstract and poetic manifestations. It can certainly be commercial and work-for-hire, but its techniques have always varied wildly.

The art world used to look at cartooning with the same level of disdain as Crumb does for the technique of cartoonists like Schulz and Feiffer. That was especially true in the 1970s and 80s when many art school professors were abstract expressionists. Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, and others have related stories about the contempt with which cartooning was viewed by their instructors, who derided their work as mere illustration or vulgar naturalism, instead of something that expressed emotion or truth.

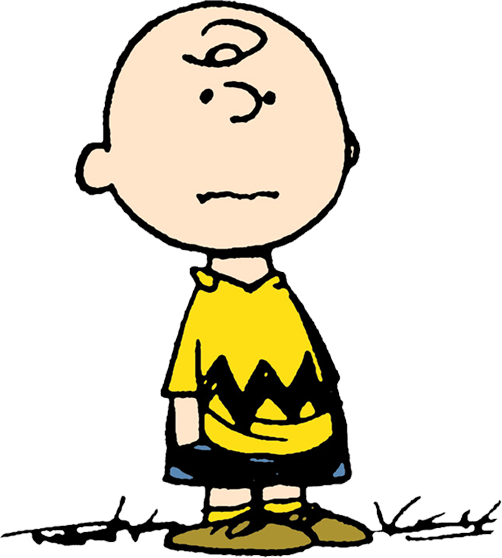

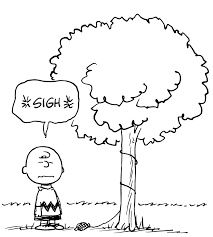

It is absurd to say that Schulz and Feiffer don’t utilize technique. It is absurd to say that their work doesn’t try to say something about suffering and the human condition. Schulz may not have used cross-hatching or intensely spotted blacks, but his line was not only filled to the brim with melancholy and frustration, it was also bursting with energy and humor. Though his figures evolved over time, there was a continuity of things like body language and especially the way his characters interacted. The deceptive simplicity of his figures evokes a joy outside of their narratives, worries, and punchlines: there is beauty in the squiggly curls that make up Charlie Brown’s hair. The plastic qualities of his line are pleasurable to look at in a way that’s different from Wally Wood’s work.

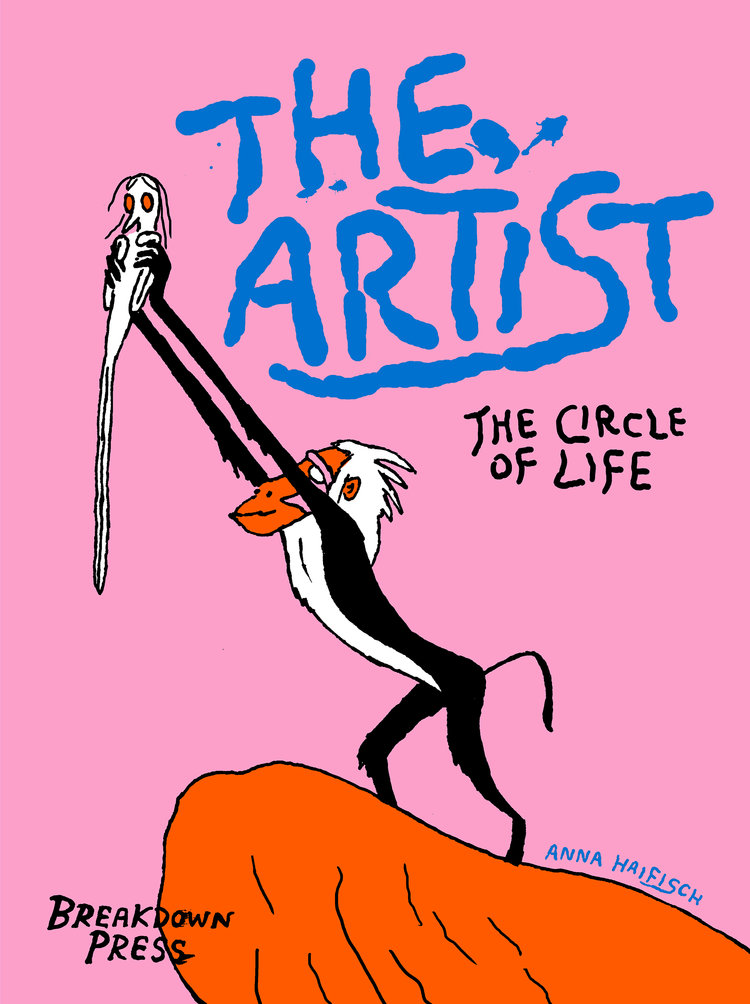

Many cartoonists today have one foot in the fine arts world and one foot in the world of cartooning. Anna Haifisch is a perfect example of this, and it’s important to understand her work in The Artist and its recent sequel, The Artist: The Circle Of Life, not as graphic novels but as collections of comic strips. There isn’t so much a narrative throughline to be found here; instead, there are motifs. The Artist struggles with creativity and the concept of being “productive.” The artist deals with rejection from their peers. The Artist deals with depression. The Artist, nevertheless, keeps trying, keeps creating, keeps thinking of the possibilities that life brings. In other words, the premise of the series in some ways is “What if Charlie Brown grew up to be a fine artist?”

There’s a sharp level of self-awareness present in Haifisch’s work. The first panel of many of her strips is a reference to pop culture (The Artist: The Circle Of Life’s cover references The Lion King, presenting The Artist as the future ruler of the tribe) or fine arts, and she flips between the two interchangeably. The very first panel of the first strip in this collection features the nameless artist sprawled across Snoopy’s doghouse, head and legs dangling over either side. Later, there’s a reference to Lucy’s “Psychiatric Help – 5 cents booth.” A heroin-addled Woodstock makes an appearance in a strip about the tragic lives of cartoon birds. In another strip, the Artist lies in a bed and then a bean bag straight out of Peanuts, then hangs out with Woodstock in a nest. Even leading with that stand-alone introductory image for each story is a Schulz reference, as the first panels of his Sunday Peanuts strips had a funny, stand-alone image. Schulz seems to be a constant touchstone for Haifisch.

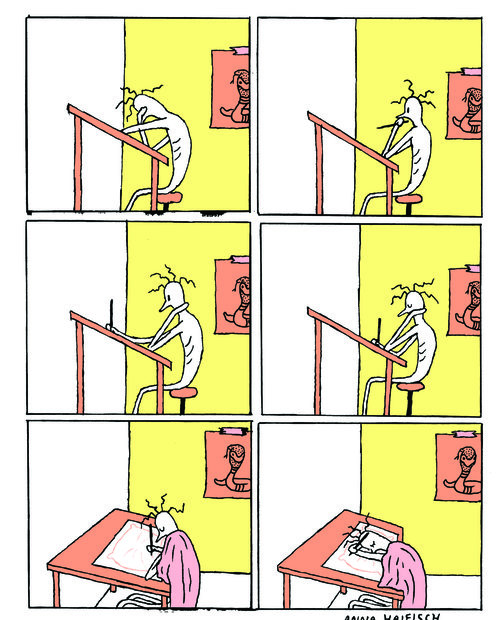

Indeed, though there’s an emotional through-line of frustration, despair, self-loathing, and longing, it’s important to understand that at heart, Haifisch (like Schulz) is all about the laughs. Schulz was all about the punchlines, though he got a lot looser with them later in his career. Despite the heavy themes in his work, his job was to make the reader laugh. It’s what he got paid to do. Haifisch doesn’t always zero in on a single punchline, but she often engages in the sort of silly absurdity that marked Schulz’ work as well. She imagines the Artist as Marc Chagall, hanging out with the Impressionist. The Artist meets Simon Hanselmann’s Owl at a dance club. The rhythm of Haifisch’s strips is different from Schulz but remains constant: an introductory single-page image, and then two to six pages in a 2 x 3 panel grid. Sometimes the grid gets vertically collapsed, but the rhythm is always the same. That allows the reader to focus on the line and the character designs in particular.

Let’s compare the ways in which Schulz drew Charlie Brown and Haifisch draws the titular Artist. Charlie Brown is best known for that squiggle of hair, the perfectly round head, ears that stick out, the constantly-trembling mouth, and his shirt with the zig-zag pattern on it. It’s an iconic image, depicting a character who is not especially handsome or remarkable. It allowed Schulz to fill that character up with all of his hopes and all of his disappointments, aspirations, frustrations, and fears. Likewise, the Artist has four scraggly hairs sticking out of his head and is so thin that we can see his rib cage in the form of three little curvy lines. He’s the very picture of “the starving artist.” His long, gaunt figure as an anthropomorphic bird is frail to the point of fragility, like one of Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures influenced by existentialism. Despite that fragility, the Artist, too, is filled with aspirations, creativity, and longing.

Both characters are funny-looking, and funny but awful things happen to them. Neither is successful, but that doesn’t stop them from continuing to try. Charlie Brown’s kites get eaten by a tree, Lucy always pulls away the football, and he can never lead his baseball team to a win. Nevertheless, year after year, he never stops trying. He alone in the Peanuts cast is an aspirational character; everyone else either is reactive (Lucy), purely contemplative (Linus), or engaged in fantasy (Snoopy). In The Artist: The Circle Of Life, the Artist has to deal with a boorish uncle who knows nothing about art, struggles at the drawing board, has to prostrate himself before an art collector, escapes into childhood comic books, and despairs at his output. The task of living authentically is Sisyphean in nature. Charlie Brown and the Artist will never “win,” but they will always try. No matter how much they despair, neither can really imagine doing otherwise.

Throughout The Artist: The Circle Of Life, my eye locks onto those four strands of hair, those three ribcage curves, and those thin, long legs. They make me laugh every time I look at them, as the Artist struggles with their art. To be sure, Haifisch is being self-deprecating on the pages where she mocks what the Artist is doing. He’s a coddled figure who doesn’t have a real job. He’s hypersensitive to criticism. He fantasizes about jail for artists where they get unlimited access to art supplies and therapy. These strips occupy a place that makes fun of its subject so accurately because the cartoonist and the Artist are so much alike. More to the point, even the things that Haifisch gently mocks are very real and important to artists, like their creative output.

The fact that Haifisch packs so much into such a simple figure is not a case of story obscuring technique, as Crumb would assert. It is an absolute triumph of technique that such a simple image could so perfectly embody such a particular set of comedic and tragic concepts. This is a set of stories about a tremulous, fragile, and imaginative artist who is frequently given to flights of fancy; what use would dense hatching and photorealism be? Just as the reader can pour their own frustrations and fears into the funny-looking, round-headed kid that Schulz created, so too can every person who has aspired to create see themselves in Haifisch’s Artist. The technique and the content cannot be separated; without this specific technique, there would be no content for this character.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply