Sugiura Shigeru’s Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke, published this past September by New York Review Comics with a translation by Ryan Holmberg, operates on what is functionally a cartoon invincibility. Just like Sarutobi Sasuke is a well-known folkloric figure in Japan, so too does everyone know of him within the stories as well; yet, because of his trickster-like powers of disguise, no one ever quite recognizes him or knows what he looks like, leading his rivals to mistake him for an easily-defeated target only for him to readily, and quite gleefully, defeat them. There is never any sense of danger or suspense; victory is a foregone conclusion. In this whimsical tonal flattening of confrontation, one thinks of Sakamoto Gojo’s Tank Tankuro (“Hee hee hee! War is so much fun!” giggles the son of Sasuke’s feudal lord at the end of the Sugiura volume, driving the comparison home). Of course, Tank Tankuro served a distinctly different purpose; much like The Adventures of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets four years prior, it was a comic not just ‘for children’ but specifically for children under a deeply right-wing regime, designed to make them amenable to right-wing ideology through the total abnegation of earnest discourse — Fletcher Hanks morals presented in a slapstick, ersatz-whimsical vocabulary.

Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke, it bears stating, has no such interests in mind, though discerning exactly what its interests are is a bit harder. Created and published in 1969, following the cartoonist’s self-imposed ten-year sabbatical from comics, the audience is frequently reminded that the comic is, in truth, an adaptation of an earlier Sugiura comic by the same name from the 1950s, itself greatly informed by the Sarutobi Sasuke comics of Tagawa Suihō from the 1930s, on which Sugiura worked as an assistant in Tagawa’s studio. (Last of the Mohicans, which Holmberg translated for his short-lived Ten-Cent Manga line under PictureBox in 2013, is another comic from the same ‘adaptation’ initiative, as is a third, as-yet untranslated work.)

As such, it naturally becomes a comic partly about the passage of cultural time. Sixty-one years old at the time, Sugiura was in the tricky position of having already influenced at least one generation that came after him while not being entirely in sync with the result of these influences (what comes to mind, at least to me, is the way Jack Kirby was viewed by the Marvel bullpen on his 1970s return to the publisher he helped make into a household brand: a dinosaur, an antique, out of step with the world around him, even though they were lucky enough to be in the presence of Kirby in what was undoubtedly his most experimental and artistically-engaged era). Consider the landscape of historical samurai and ninja manga at that time: this was 1969, some seven years after the debut of Hirata Hiroshi’s Bloody Stumps Samurai; Shirato Sanpei’s Legend of Kamui was five years into its run. The ur-text Lone Wolf and Cub was right around the corner. This was no time for jokes or whimsy or for cartoon violence; this was a bodily, political, heady era, a time for blood and sinew. Even in the shōnen realm, where Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke nominally belongs, the reigning comics of the day were more Ashita no Joe than Bat Kid.

This disparity, more than anything, is what defines the general tone of Sugiura’s writing to me. With a one-liner pace so frenetic it would make even Rodney Dangerfield dizzy, this is a book so forcefully unserious that it almost scans as resentful; indeed, I would go one step further and say that Sugiura’s jokes, at some point, stop being jokes altogether. As he makes several references to himself, going back and forth between describing himself as an old geezer and, sarcastically, as an up-and-comer, Sugiura writes in that overly-self-effacing tone of a person who knows that the jokes are not entirely unfounded; that maybe he is, in fact, out of place. At some point in Last of the Mohicans, a character, on carrying out a bloody assault, exclaims “Blood-colored elegy!” — by evoking, supposedly whimsically, Hayashi Seiichi’s Red Colored Elegy, serialized three years prior to the [re-]adaptation of Fenimore Cooper, he forces his audience to consider the odd fact of the two creators’ simultaneity. An offhand remark on filial piety in Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke, which Holmberg interprets as a snipe at Tsuge Yoshiharu’s landmark short “Nejishiki” (or “Screw Style,” or “The Stopcock,” or however the next translator may choose to render it), achieves much the same purpose, though in a manner easier to miss.

Alongside the chronological shifts in the comics field, the other plane remarked upon in Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke is the geographical. In his accompanying essay, Holmberg discusses the concept of batakusai, or ‘butter-stink,’ a derogatory term against Western influence, manifesting in the arts as works that were too evidently evocative of the western hits du jour, be these (to use the translator’s own examples) Charlie Chaplin, Superman, or Walt Disney. What Holmberg does not explicitly touch on, but which is of course unmissable, is the nationalism rather inherent to the term: the idea that Japanese culture must remain integrally and purely Japanese and that external influences must be either relegated to secondary importance or else shunned altogether.

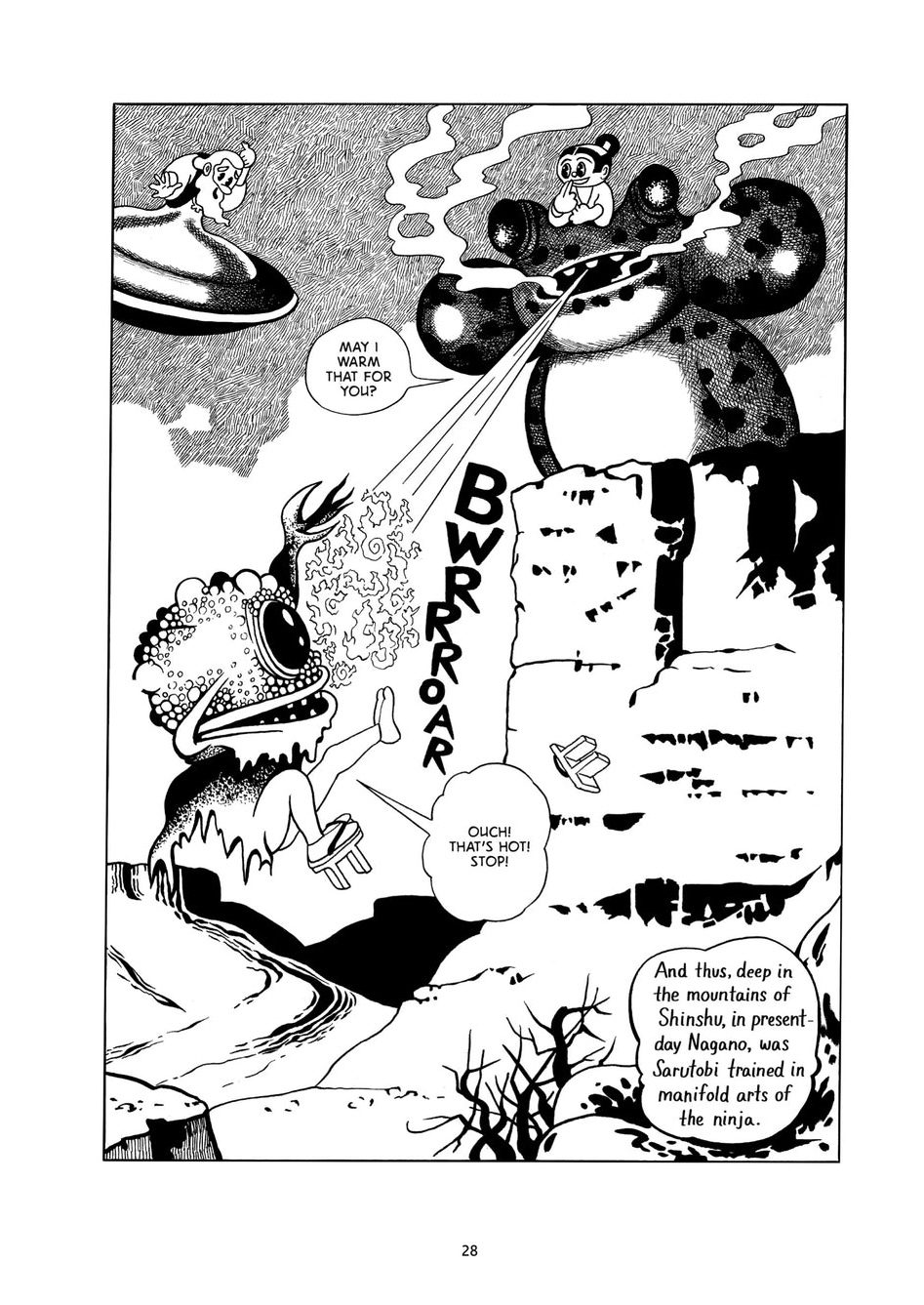

On the visual level, one observes the frequent stylistic changes attempted by Sugiura. Alongside his baseline style — flat, rubbery, lumpy, with a freewheeling approach to depth and spatiality — appear forms with heavily-wrought, meticulously-hatched solidity. When I say ‘alongside,’ I do mean this literally: these forms are designed to appear not separately from the baseline but within the same panel-space; the style-change is not a sweeping exercise a la Matt Madden, but a disruption to the intrinsic sense of reality.

And yet this eschewing of semiotic congruency, in which various perceptual planes collide (and rather violently at that), is not the sweeping surrealism of, say, the more opaque Maki Sasaki, nor is it comparable to the later détournement of Kikuchi Hironori (most familiar to Anglophone readers through his occasional contributions to kuš!), whose overall endeavor is an alchemical maximalism that is to Sugiura and Tezuka what Jim Woodring is to Fleischer animation. No, when these stylistic changes occur, it is, fundamentally, in the way of a non sequitur that calls attention to itself (often in the form of the characters making ‘cutesy’ meta remarks poking fun at the cartoonist), as if to say, this comic is not supposed to look like this.

The Sugiura of 1969, then, is not your typical ‘butter-stinker.’ According to Holmberg, the cartoonist’s bibliography can be divided, roughly, into two stages. His earlier works, up to about 1952, exist on one visual plane; whether the character drawn was Sarutobi Sasuke or Betty Boop, they are drawn with the same style, the same aesthetic approach (it is of little importance whether Sugiura had any deeper belief in artistic internationalism-unitarianism or simply drew characters like Betty Boop in his own style to cash in on the trends of the day, because either way it is the style, not what is depicted, that is of the essence). The second stage, starting from that point on, saw Sugiura begin to overtly account for these cultural differences, drawing different characters in his approximation of their ‘native’ style. It is for this reason that, when the cartoonist pits Japanese folklore, in the form of ninja and samurai, against the corresponding American equivalent (the Western), the reader can easily tell which is which without even paying any mind to their clothes: when Jesse James and Buffalo Bill make their cameo, they are rendered in a realer-than-real style, the platonic ideal of American cowboy comics, out-Severin-ing the Johnest of Severins.

One thinks of Žižek’s observation of Kung Fu Panda as a movie that ostensibly mocks, yet nonetheless enforces, its own ideology: by evoking specific styles and then judging them against the standard of his own style, Sugiura props up categorical divisions with a distinct aesthetic conservatism. If there is any appreciation for that butter, it is only ever from a safe distance. What we have here is a dual stylistic appropriation — of Americana, on the one hand, and of fine/‘serious’ art on the other — in a way that forcefully rebukes both, or, at the very least, ‘puts them in their place.’ An interesting contrast would be, perhaps, Black Blizzard by Tatsumi Yoshihiro (1956, English translation by Taro Nettleson published by Drawn and Quarterly, 2010), a work that demonstrates the growing pains of a theretofore ‘children’s’ artist trying, and mostly failing, to really figure out, on the thematic level, what an ‘adult comic’ would look like; Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke does recognize the possibility of something beyond mere entertainment, but nonetheless bristles at the notion.

It is at this point that we must talk about translator Ryan Holmberg as well. Holmberg, of course, has by now established a de facto monopoly as pertains to alternative manga and gekiga, far exceeding any competitors in his occupation of ‘space’ within the sphere. Yet I cannot help but feel that perhaps this operates to his detriment, as his handful of characteristic tics are applied to functionally every single one of his translation subjects. Although I do not speak Japanese, I do work as a translator (from Hebrew) for a living, so I’m closely familiar with that tension between the intent of the source and the elegance of the end-product, and the balance that must at all times be maintained. With Japanese, a language that, to my understanding, is far more syntactically disparate from English than Hebrew is, there is an even greater element of stylistic liberty, which Holmberg entirely overlooks. At all times, he gets his point across serviceably, but his prose is entirely stiff and inelegant. See, for instance, from Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke, this distinctly Holmbergian construction: “The first submarine to be named ‘Nautilus’ was designed by Robert Fulton in France in the late 18th century. It never made it past the test phase, however.” From a fairly simple conveyance of information, several questions arise: why, for instance, is “however” at the end of the second sentence? Why, for that matter, are these two sentences not one to begin with? To be sure, this clipped, matter-of-fact syntax would work far better when read aloud to a live audience — a form in which winding multi-clause sentences run a greater risk of confusion — but in writing it is shabby at best. (My editor reads my sentences, clauses nested within clauses several times over, and sets his eyes to the Google Docs ‘add a comment’ button to lodge his weary dissent.) (Editor’s Note: True)

Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke is, indeed, a very compelling comic to talk about, with the politics of its cross-generational and inter-cultural exegesis serving as fertile ground for analysis. But the problem is that, as far as comics go, it is not a particularly entertaining one; even setting aside Holmberg’s clunky phrasal tics, its jokes are almost universally unfunny, which becomes a problem when the reader is so aggressively bombarded by them that they forget (a) that there is a plot, let alone (b) what that plot is. Of course, at least from a commerce perspective, I have historically proven to be in the minority as pertains to this particular comic — in a quote translator Holmberg has shared in several of his writings on Sugiura, when Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke (1969) appeared on shelves it was Hayashi Seiichi (he of the ‘blood-colored elegy!’) who worriedly wrote that “it seems like there is going to be a strange Sugiura boom,” a vision that soon came to pass. Sugiura continued to make comics after Last of the Mohicans—his last comic came out in 1996, so, in lieu of juxtaposing him with Hayashi Seiichi, the audience may now picture, in their mind’s eye, this eighty-eight-year-old cartoonist standing next to One Piece’s Oda Eiichiro — and, at least judging from what little has been made available to me (“Jiraiya the Ninja Boy,” published in Raw #7, 1985; untranslated pages from the cartoonist’s last work, 2091: A Space Odyssey), it would appear that these subsequent works have all been of more or less the same stylistic molds varying only according to the whims of age and passing time. His audience, for its part, appears to have more or less lapped it up, at least enough to ensure employment in a volatile market.

But, if there is any interest or any inherent appeal within these comics, it is only in their demonstration of how an artist starts out within the context (aesthetic, stylistic, semiotic) of his surroundings, and then, over time, first expands his vocabulary then withdraws further and further into his established idiom, corresponding with those surroundings less and less.

Earlier, I compared Sugiura to Jack Kirby in his stature, and, indeed, here as well, I find Kirby to be an apt equivalent: his Fourth World opus is a transcendent piece of comics, but Silver Star is interesting mostly in its nigh-archetypal distillation of longstanding Kirby themes. And yet, it was Kirby who said the following to a group of convention attendees:

You fellas think of comics in terms of comic books, but you’re wrong. I think you fellas should think of comics in terms of drugs, in terms of war, in terms of journalism, in terms of selling, in terms of business. And if you have a viewpoint on drugs, or if you have a viewpoint on war, or if you have a viewpoint on the economy, I think you can tell it more effectively in comics than you can in words. I think nobody is doing it. Comics is journalism. But now it’s restricted to soap opera.

Did Sugiura Shigeru have an equivalent viewpoint? Possibly, though not enough of his works have been translated for me to feel comfortable making any sweeping claims. But Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke, like Last of the Mohicans, certainly doesn’t think of comics in terms of drugs, of war, of journalism, of selling, of business. Indeed, it thinks of comics in terms of very little beyond Sugiura Shigeru.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply