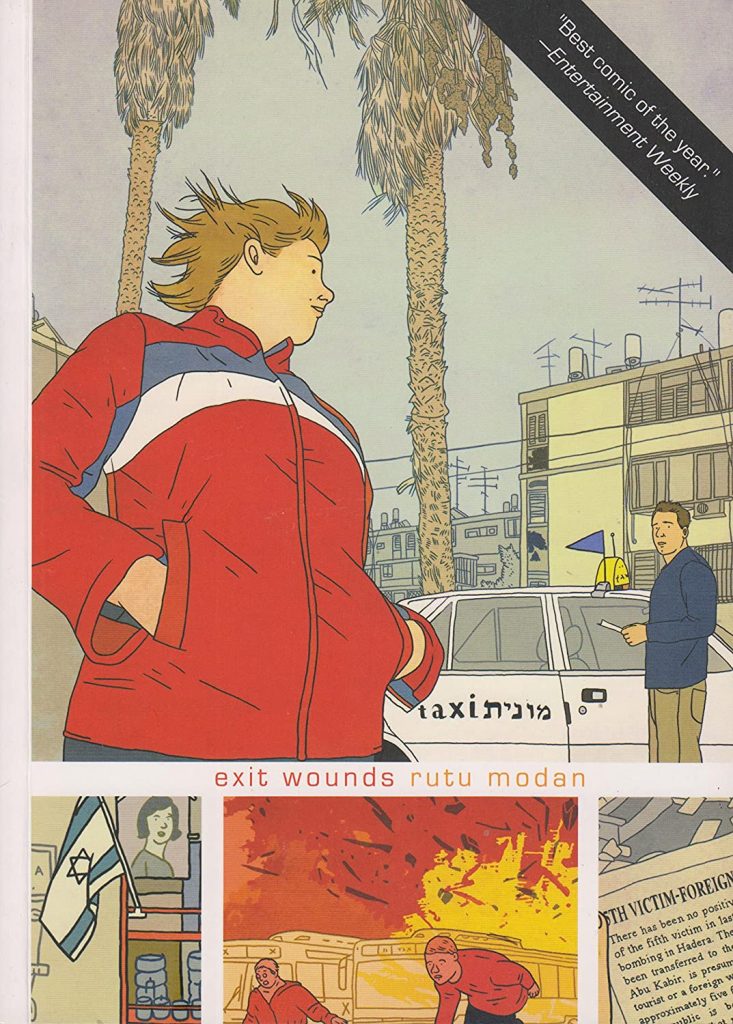

Today, we have a special treat for SOLRAD readers. Tom Shapira, contributing critic at SOLRAD, sat down with Rutu Modan for a lengthy interview about her history in comics, her most recent work, and all the space in-between. Modan’s latest book Tunnels was recently acquired by Canadian comics publisher Drawn & Quarterly. Modan won an Eisner for her graphic novel Exit Wounds in 2008, and has consistently been praised by critics, creators, and readers alike. Her work has been celebrated over the past 30 years in Israel. She lives in Tel-Aviv with her husband and two children.

This interview was conducted in Hebrew and translated into English by Tom Shapira.

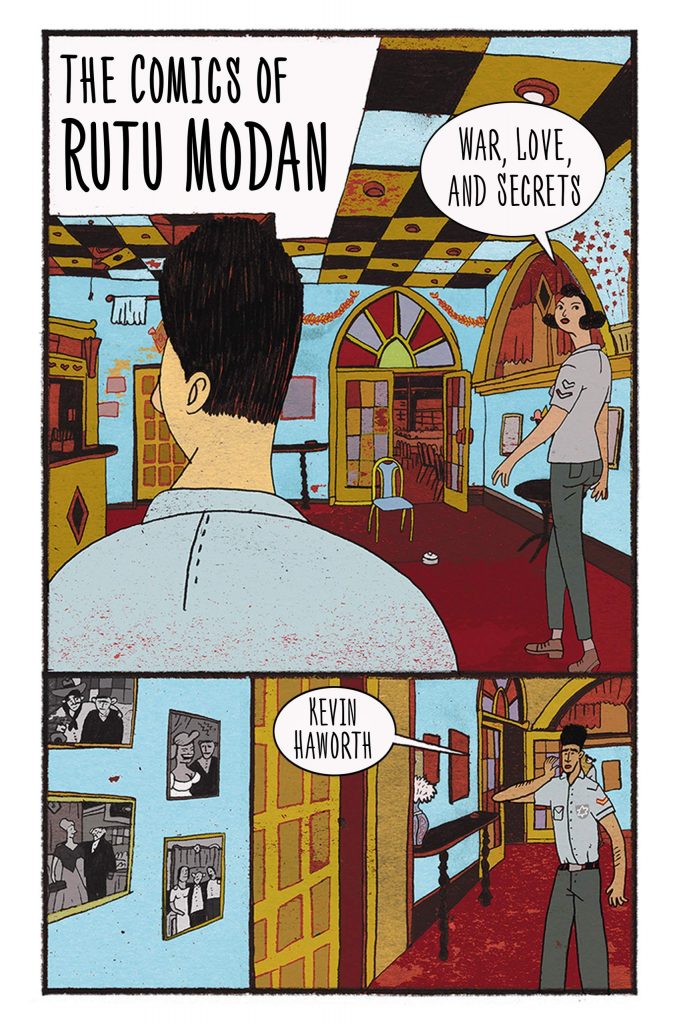

Tom Shapira (TS): 2019 saw the publication of The Comics of Rutu Modan from The Great Comics Artists series of Mississippi of University Press. This is the first time a creator from Israel was named alongside the likes of Jack Kirby, Linda Berry, and Osamu Tezuka. One can say you are the most well-known comics artist from Israel, how does that feel?

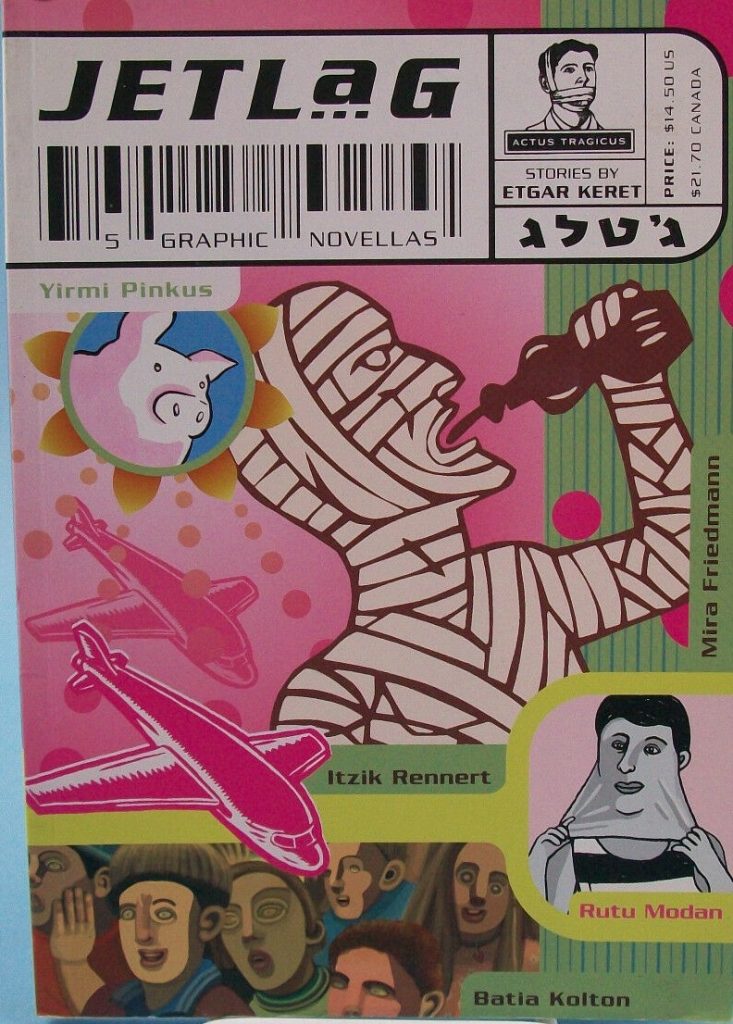

Rutu Modan (RM): How does it feel? It’s great. Being recognized is important to every creator. I am not sure I “represent” the Israeli comics scene. I turned outwards very early. When we founded Actus [Actus Tragicus – Israeli comics collective] in 1995 we had an international aim from the get-go. We did comics in English, we published it abroad, went to foreign festivals. When we went to Angouleme in 1996, Yirmi [Pinkus] and I were considered “interesting”. Everyone asked, “Are there comics in Israel? Do you draw them while riding a camel?” We became the face of Israeli Comics because we were the thing people knew. We got a lot of opposition for it from the local scene. It’s funny, because today it’s obvious you can publish to the whole world, but back then people came at us for just for doing that.

We didn’t, or at least I didn’t, set to represent Israeli comics; I just wanted to make comics. I started in 1990 with a newspaper column. After that, I worked with Etgar [Keret, famed Israeli author]. Our book, Nobody Said It Was Going To Be Fun, sold well, even in terms of USA sales. We shifted about 5,000 copies. Still, no one was willing to publish me in Israel. My friends and I just wanted to make comics and for people to read them. So we said, “let us expand the audience, let’s make it available outside the local scene.” That’s how it developed, we did our collections and, after a couple of years, I got the offer to make Exit Wounds from the fine people at Drawn & Quarterly. Things just kept moving. I did the work, knowing the audience was not limited to Israel.

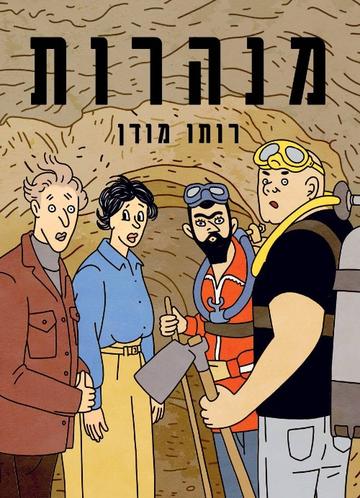

TS: Let’s talk about the new book, Tunnels, which already came out in Hebrew, and also in German, I believe…

RM: The German version just went to print, in French very soon. In English only in October 2021, COVID-19 really changed everything. We are supposed to see it in Spanish and Italian as well, but I don’t have a date for it.

TS: This is your largest book, not just in terms of length but also in terms of content: there’s a massive cast of characters, a plot that goes all the way from Biblical times to the present, and lots of thematic interest. Did it feel daunting working on something like this?

RM: It’s scary. It’s really scary. Every phase is scary: I start writing and I tell myself “I can’t do that.” Then I storyboard, which is very critical. Then I work with actors [author’s note: a lot of Modan’s work is done with live models]… my first response is always, “I can’t do it, someone else please do it for me.” But no one is going to do it for me, so I end up doing it myself. When I start I never know where it will all end. I have the germ of an idea, some sentence popping up in my brain, a spark. It takes some time until I decide it could become a graphic novel. I need to feel there’s a strong potential for the story there. Potential in terms of allowing drama and tension already at the base of the idea, before I develop the story. It’s important that the idea could be like a Velcro – that it could stick to other themes and carry them. It should be strong enough to keep me interested for years. Really, every story takes me more and more time, which is a bit disturbing.

There is also a dimension of personal development. I don’t know what the work is going to be like when I start it, only when it ends, so the story tends to develop and become more complex, more characters, more topics. In The Property, you have about five main characters. Everyone else is incidental, they appear on the page and disappear, like extras in a film. In Tunnels, you have more roles and even the side-characters, I feel, could lead a graphic novel by themselves. Everyone is complex and arrives with their own personality and history. It’s important to me because the story is all these characters and their connections; you need them all together.

There is also the political side, the use of the [Palestinian-Israeli] conflict. It took me ages to figure out how I can present this thing – not to make it into a “good vs. evil” thing, but show the situation with the complexity I see in it.

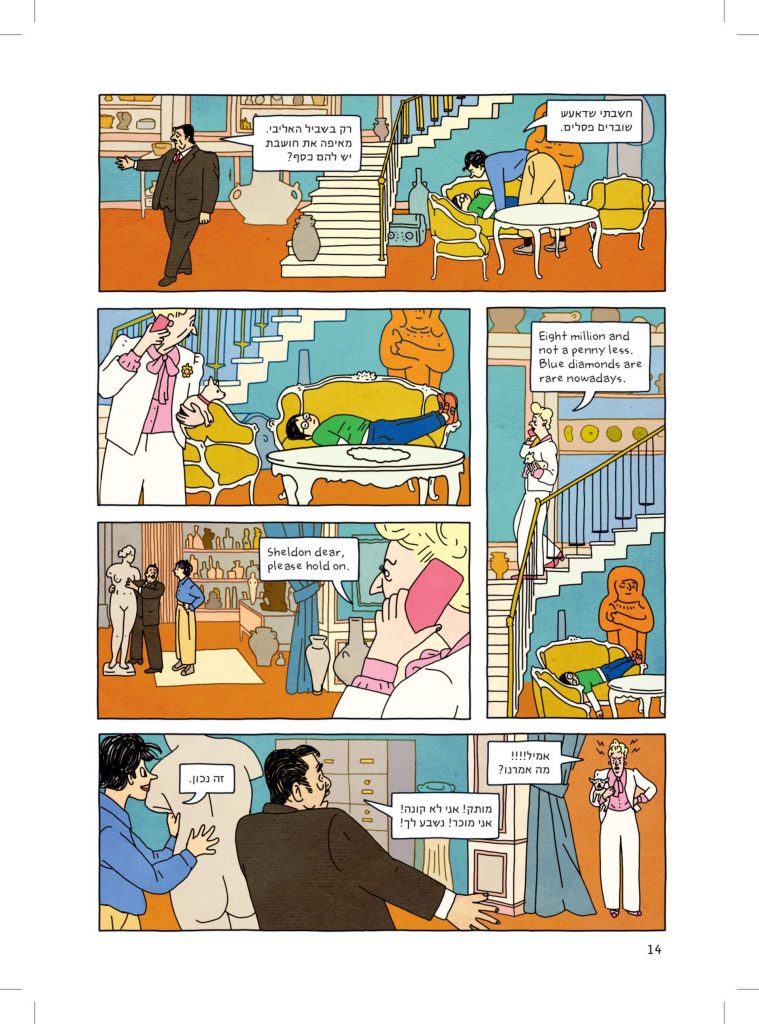

TS: As a counterweight to all the heavy political stuff, this is also a very funny book. Humor has always been a part of your work, but this one made me laugh out loud several times; I am reminded of the latter works of Herge, when he became conferrable with the character-interaction and the slapstick. Do you use humor as a “balance” or is it something inherent to you?

RM: Oh, inherent. It’s just the way I look at the absurdity of our situation. Humor is a way to deal with the world. When I say the conflict is “humorous,” I mean it in the way it can show how foolish we are. Which, I feel, is also a political statement. Also, comedy is the ultimate test of a creator’s skills – the audience either laughs or it doesn’t.

TS: There’s a lot to admire on a technical level in the book, I think a lot of people would particularly notice the scene with Zuzu fighting the two teens in the village, with a completely white background.

Rutu Modan: It was an interesting scene for me, for various reasons. I have many fighting scenes despite the fact that in real life I don’t get into fights. I grew up with sisters who didn’t tend to fight; I am also not a very strong or highly coordinated person. In the end, it’s just fun to draw – it’s like a dance, it involves physical activity we do not engage with on a daily basis.

I work with actors. I usually do pretty tight storyboarding, making sure what happens in each frame. This one scene I storyboarded less tightly because I knew I was working with physical actors and I wanted them to bring something from themselves. I knew if I collaborated with the right people they could give it a better interpretation than I could.

There are two Palestinian brothers in the story, and when I storyboarded it originally, the younger brother was always smaller. That fight scene was built on him being the weaker side, and so it remained until the day of photography. I picked the actor from an audition shown to me by director Eran Kolirin. In the audition, he was sitting down and he had a great face. When he came in the day of the shoot I finally saw him – two meters tall, broad shoulders. Turns out he’s a champion heavyweight boxer. The guy playing his brother is just of average height. Looking at him I realized that the whole scene should change. The people playing the teens attacking him were dancers – very acrobatic and physical people, they were tiny and slim compared to him. The change of sizes changed how I understood that scene; now it’s not two strong people picking on a weaker person, but one strong against a weak pair – which has a lot more dramatic potential.

When the shooting started I told them, “He can beat you but you are too stubborn to quit; he can knock you down but you just get up again.” We improvised the scene. It was one of the best experiences in my professional life, these people just flew through the air, utterly fearless. I had ideas, they had ideas, and we just kept on trying stuff. When the time came to draw it I realized I don’t need a background – the fight was the important bit.

That, I think, was the most important lesson I learned from Herge. They say I am influenced by him, and it’s true, but for me, it’s not about the line but about his grasp of page composition. Herge could draw pages packed with tiny panels with tons of activity and action, but you never get lost in these pages. Ligne claire to me is not about the line but about the clarity of the storytelling. You can see in almost every spread of his, one huge panel packed with details, a harbor filled with ships, and then the rest of the panels are more sparse. Because you have that one big, dominating image, your mind projects these details on to the rest of the page. My personal tendency is to over-use detailing which means that particular scene was very releasing – this is my book and I can do what I want with it, let go of the unnecessary clutter. So this scene represents a meaningful shift for me.

TS: As you’ve mentioned, Tunnels is to come out in 2021 from Drawn & Quarterly, who became your “house publisher” in a way, you’ve got a lengthy history with them…

RM: I first worked with them in 2004, they asked me to take part in one of their anthologies. It was a sort of a test drive and, after it succeeded, Chris Oliveros wrote to me to ask if I wanted to do a graphic novel. Which was my dream for ages. That short story was about a suicide attack…

TS: That was “Jamilti,” right?

RM: … and he said I could whatever I want as long as it was local. This was when Persepolis was all the rage and I was a bit suspicious. I wrote back that I would love to do a graphic novel, but that it wouldn’t be the “Israeli Persepolis”, that’s just not who I am. He said that was fine, they just didn’t want something that could happen in Canada. I promised them it wouldn’t be. Exit Wounds changed everything.

TS: It was a massive critical hit. You won an Eisner, Joe Sacco loved it, Douglas Wolk loved it…

RM: It changed my life. The book came out in several languages, and one of my favorite things is traveling the globe, and the book helped me to get to so many places and meet many people. You don’t become a creator just to travel, but it sure is fun. The most important element of success is that I could focus totally on art. Since the book came out, 2006, this is basically what I do. I teach illustration and do some other works but graphic novels take most of my time. It’s the thing.

TS: From Exit Wounds, you’ve moved on to The Property. It was a longer, more self-assured work. It’s also interesting because it is a story about an Israeli moving to Europe, which is kind of what, metaphorically, happened to you: from doing a story about Israel to doing a story about Europe.

RM: True, though in my eyes a story about Israelis in Poland is basically a story about Israel. I come from Polish stock, Warsaw stock to be exact (it’s very important for us to be precise). To me, The Property is still an Israeli story. However, when I started to work on it I was living in England with my partner, so maybe that idea really is borne of a foreign soul.

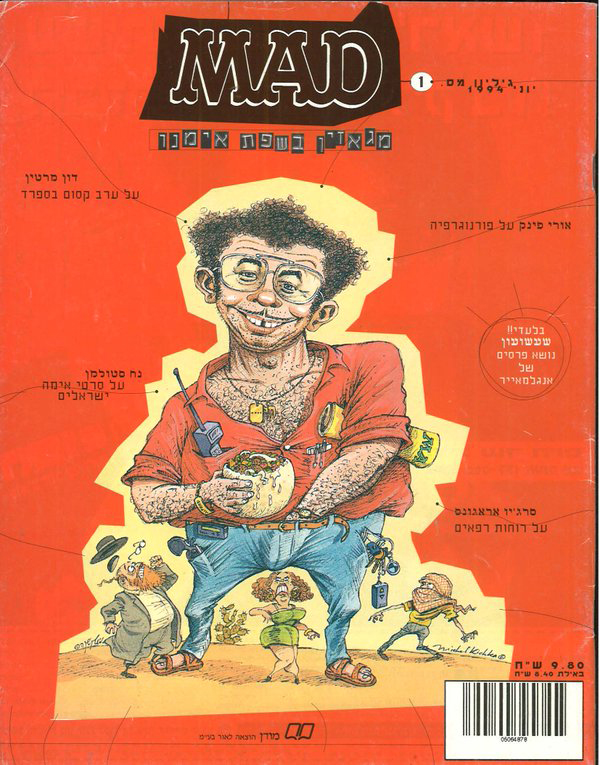

TS: Before Exit Wounds, even before Actus Tragicus, you were in the Israeli version of Mad Magazine, which was radically different from the original.

RM: “The follies of youth” you could call it. I sort-of miss that period. It was round about 1994, we were fresh out of Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Yirmi Pinkus and me. My uncle, Odded Modan, was a publisher with a lot of time for comics (he published Uri Fink) and loved the idea of local Mad. They were selling their international rights for localized versions back then.

It was supposed to be 75% American stuff and 25% local material. My uncle asked me to edit the project, despite my lack of experience in editing and production. I told Yirmi, “Let’s go for it.” We were more on the underground comix wave at the time and, so, we kind-of coerced Mad into being what we wanted. We brought on Tamar Karavan, who was a graphic designer at the time and today is a highly rated photographer and fashion personality, who was very into punk. It was very much in that late 1980s / early 1990s aggressive esthetic

TS: Like Raw gone Mad.

RM: We wanted to be Raw, but we got stuck with Mad instead. The fun bit was realizing we could pick and choose American stuff from all eras; we ordered a ton of stuff from the 1950s. We took what we wanted and we created this chimera that didn’t please anyone. The people who liked alternatives couldn’t stand Mad’s stuff, and the people who liked Mad didn’t like the local material which was mostly alt stuff. It was a total failure, gone in 10 issues, but like any other grand failure, there was also a positive side for me. I learned a lot about editing, production, and printing, stuff that became very useful later on. It also led directly to Actus Tragicus. We said, “We’re going to lose money either way, so might as well do stuff that we like.” If we are going to fail – let’s do it on our own terms. Actus kept going for about 12 years.

TS: When you studied in Bezalel, did you think of yourself as a “comics artist?” Was there a “comics scene” in Israel?

RM: No, when I grew up there wasn’t really comics. Here and there in limited quantity; one Tintin album that was translated when I was still young (more came much later), some translated issues of Popeye and some illustrations in Haaretz; it was all very sporadic, I never quite realized it was a medium by itself.

On the other hand, I was always doing comics. I wouldn’t call it “comics,” but I was illustrating stories since a very young age, and I would even use speech balloons and caption boxes because I already some vague consciousness of it. I didn’t say, “I want to be a comics artist,” I just became one. When I arrived at Bezalel, Michel Kichka [Israeli cartoonist of Belgian origin] opened the first course in comics. For the first lesson, he just brought a ton of stuff, from Raw to Tintin and other Franco-Belgian books. For the first hour, we just looked at the books, and by the end of it, I knew.

TS: You had a switch in the brain?

RM: It was like falling in love. When you meet someone and you just know that’s the “one.” That was what I wanted to do. A couple of months after that I had a column at a local newspaper and since then I never stopped – columns, short stories, graphic novels…

TS: Did you have a similar transformative moment when you decided to become an artist or was it more gradual?

RM: This is vaguer. I grew up in a family of doctors. No one did art, not only did we not do it – we didn’t like it. They would take me to museums, as an educational experience, but they could never believe it was a profession. My father believes in one real profession – M.D. If you are not good enough to be a doctor, and obviously his girls were good enough, then you are a loser and you can become a lawyer or an engineer. If you really lack any discernible skills, you can be a dentist; but I kept thinking about art as a possible profession. During my military service, a friend told me about entrance exams for Bezalal and we signed up. That’s how it went. Once I decided to do it I had no doubt this was going to be my future. I fought really hard with my dad over it, he expected more from me and my good grades. We argued; and arguing only helped strengthen my resolve.

TS: The rebel artist.

RM: He gave up in the end. For years later he would tell me, “With your hands, you could’ve been such a great plastic surgeon.”

TS: We came all the way from the present to your past, so let’s ask about Rutu of the future. You just finished your biggest project yet, are you already thinking about the next one, or are you still feeling in the process of making Tunnels?

RM: As far as I am concerned, it is over. It is ready for print. Everything else is other people’s job. There all sorts of little things, but the project itself is behind me. I am no longer sure how it relates to me, how I even did it. It’s hard because for years that was the thing filling my time and thoughts, guiding me and giving purpose. Suddenly, it’s gone. The last few times I really went through a crisis after finishing a book – that sense of emptiness. This time I had a plan. My family relations can suffer from my work, me throwing myself into this thing 20 hours per day. I told myself I’ll take six months off for just teaching and reading and traveling. Obviously, Covid19 spiked that notion. I am not going anywhere but I try not to freak out over it. I have plans for smaller projects in the near future – but still in the future. I want to give it time and enjoy doing nothing.

TS: Seeing as SOLRAD is often aimed at younger creators and emerging talent, if you could give one piece of advice for up-and-coming artists, what would it be?

RM: It’s not particularly original but – “you just have to do it.” I realize it could be difficult, but if you want to make comics, if this is what you love, you should go for it. It’s good to do what you love, even if it is only on the weekends or in the afternoons – as long as it is coming from true commitment. It’s not easy for creators these days; when I first broke out there all these new avenues – lots of new newspapers and the internet as well – new spaces calling for new talent beyond the local market. People were looking for “the other” and “the outsider”.

In Angouleme, up until the 1990s, they didn’t really care about foreign stuff. All the categories but one were aimed at French material; until suddenly something changed and they became more open. On the other hand – today it is easier to reach an audience. There will always be difficulties. What’s important is to try and focus. I am going to sound a bit “new age-y” with this but here goes – try and make it so that you do what you love, that’s everything really.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply