Tânia A. Cardoso is an urbanist who uses comics and illustration to investigate the city. Based in Rotterdam, she is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam investigating the relationship between “the city” in the abstract sense and its pictorial representations.

Since 2010 she’s been part of various exhibitions both in her native Europe as well as in China and Brazil. She’s also well acquainted with praise: her Master’s thesis on representations of the urban in comics was nominated for Brazil’s ANPUR 2015 award; in that same year won the Netherlands’ Worldwide Picture Book Illustration Competition; most recently, in 2019, she was nominated for France’s Women Cartoonists International Award.

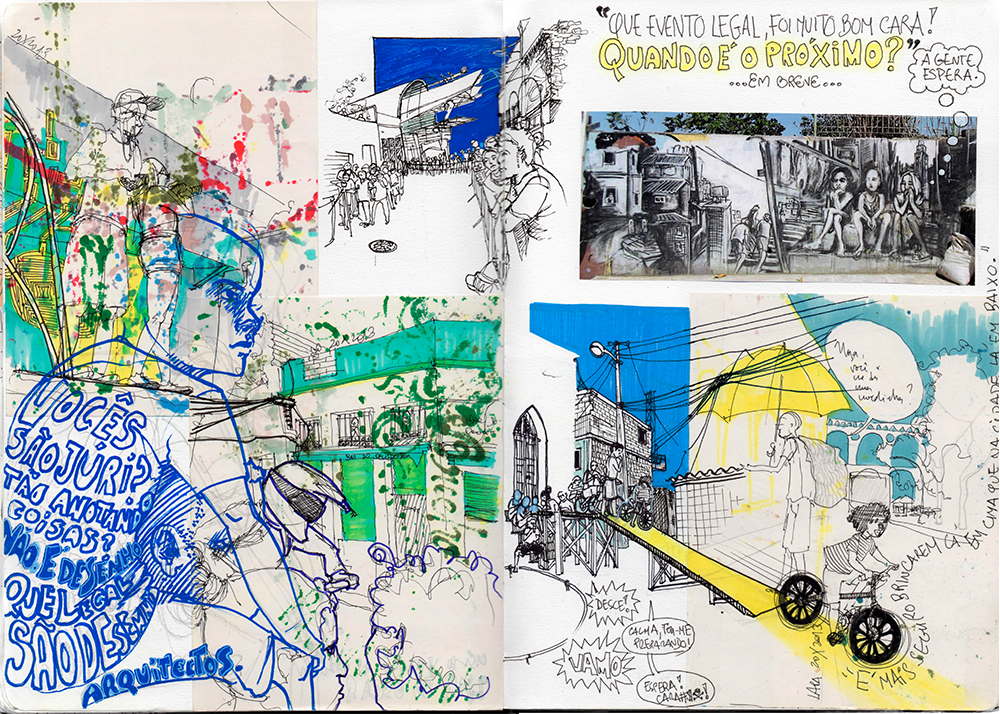

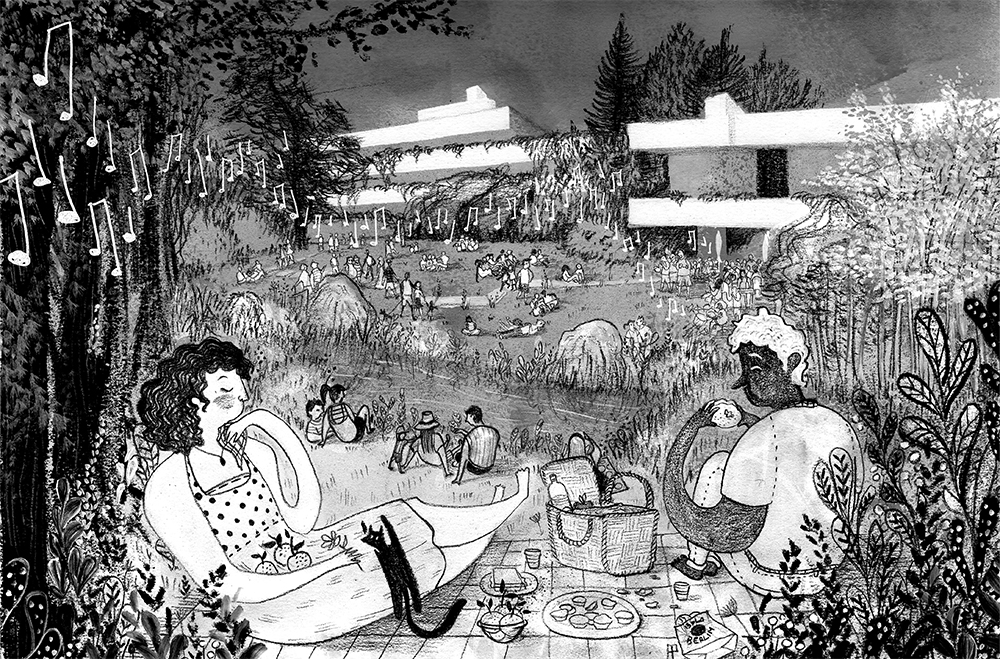

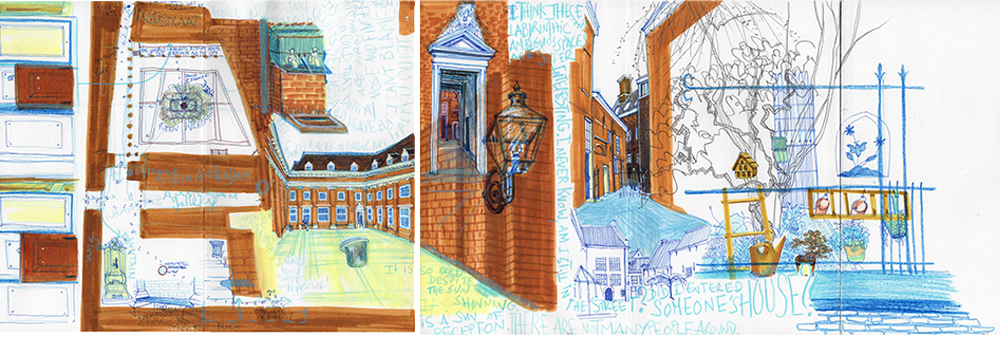

Cardoso’s art ranges from folksy painting styles to ligne claire inspired inked work. What grabbed my attention is her ongoing series of collages produced in situ, wherein Cardoso combines cartooning, architectural illustration, and painting to depict whatever city she’s drawing in to capture all its multifaceted glory. Cardoso and I had the following lengthy conversation over email at the end of 2020 and beginning of 2021 and discussed her background in the Brazilian comics scene, the impetus behind her work, the relationship between comics and urban studies, and much more besides.

Nicholas Burman [NB]: I want to start by asking you about your relationship with comics and drawing growing up. Were you reading a lot of comics when you were a kid or was that something that came later?

Tânia A. Cardoso [TAC]: My interest in comics has fluctuated. When I was a child I drew a lot but didn’t read many comics. I mainly read comics during summer breaks, small weekly books from Disney like Donald Duck and José Carioca or Brazilian author Mauricio de Sousa’s Turma da Mônica. Sometimes I would read my uncles’ bande dessinées, like Uderzo and Goscinny’s Asterix and Obélix, and Morris’ Lucky Luke, but I didn’t connect with the stories. I liked Hergé’s Tintin, but I used to watch the cartoon, only later did I read the albums, as graphic novels are referred to in that tradition.

I became more interested in comics when I discovered Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Waterson and Mafalda by Argentinian author Quino. These books were so much more interesting and funny to me at that time. But it wasn’t until I started architecture school that I started collecting and drawing comics. I still remember as if it were yesterday: my first-year architectural project professor brought a bunch of comic books to the class. He showed us albums such as Peeters and Schuiten’s Les Cités Obscures, Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese, Will Eisner’s A Contract with God, and also some architectural projects and theories from the 1960s and ‘70s in comic book format by the Archigram collective. It really changed my perspective on comics and their potential, so I did some small courses and masterclasses parallel to my university course. My interest really expanded, and I was reading comics from all over the world and learning to make my own. From there to where I am today, it feels like a natural progression.

[NB]: Are there comics or illustrators from Portugal that you grew up reading? Or is Portugal quite dominated by comics from other places, such as those in the bande dessinée tradition?

[TAC]: Not really, Portuguese comics were for a more adult audience when I was growing up, I guess. There is a big political cartoon tradition in Portugal, and a few comic artists and illustrators, but they were not very popular amongst children in the ‘90s. There was a bigger prominence of foreign authors at that time. Nowadays, I can’t say for sure because I have been living abroad for ten years now, but it seems to me that Portugal is still quite dominated by North American comics and Bande Dessinée. However, I have seen more openness to national authors in Portugal and abroad.

Besides the traditionalist Amadora BD international festival, a higher number of International BD Festivals and Comic Cons have risen in the country, I think the development of the online format has helped a lot, and the originality of various children’s picturebooks really stood out in Bologna’s Fair.

Publishers also seem more interested in working with comics (in small numbers), and other institutes such as museums are also more interested in using illustration for their content communication. Some comic book shops turned independent publishers also encourage national productions, along with the selection of international mainstream and underground comics and illustrated books. It is still a small group of professionals though.

[NB]: Let’s talk about your move to Brazil in 2010. Why did you go there, and how did that move influence your style and approach? Did you come across artists there (both from comics and elsewhere) that have become important touchstones for you?

[TAC]: I finished my Architecture degree in 2008 and, after working as an intern in an architecture office, I realized that profession was not for me. I still loved architecture but decided to work as an illustrator full-time with an art agency in Lisbon. This was right after the 2008 economic crisis so there wasn’t much work in Portugal, and what was about wasn’t well paid. As it turns out, Brazil was having a good moment in terms of architecture work and creative work as well (because of the upcoming World Cup and Olympic Games), so my partner and I decided to move.

It was in Rio de Janeiro that I decided to continue my academic work at the University and to really dive into the world of critique and representation of the city through comics during my Master’s in Urbanism. When I was living in Rio de Janeiro, there was this monthly event called “O Feijão Ilustrado” (The Illustrated Bean) where people would meet to draw, drink, and talk. It was super fun and you could mingle, talk, and create connections. I met some of the most influential people for my work there: the illustrator Renato Alarcão, the historian and comic artist Flávio Pessoa, the comic artist and editor of Beléléu magazine Tiago Souza Lacerda, and later – at the Comic Cons – the comic artists André Diniz, Rafel Coutinho and, of course, the twins Gabriel Bá and Fábio Moon.

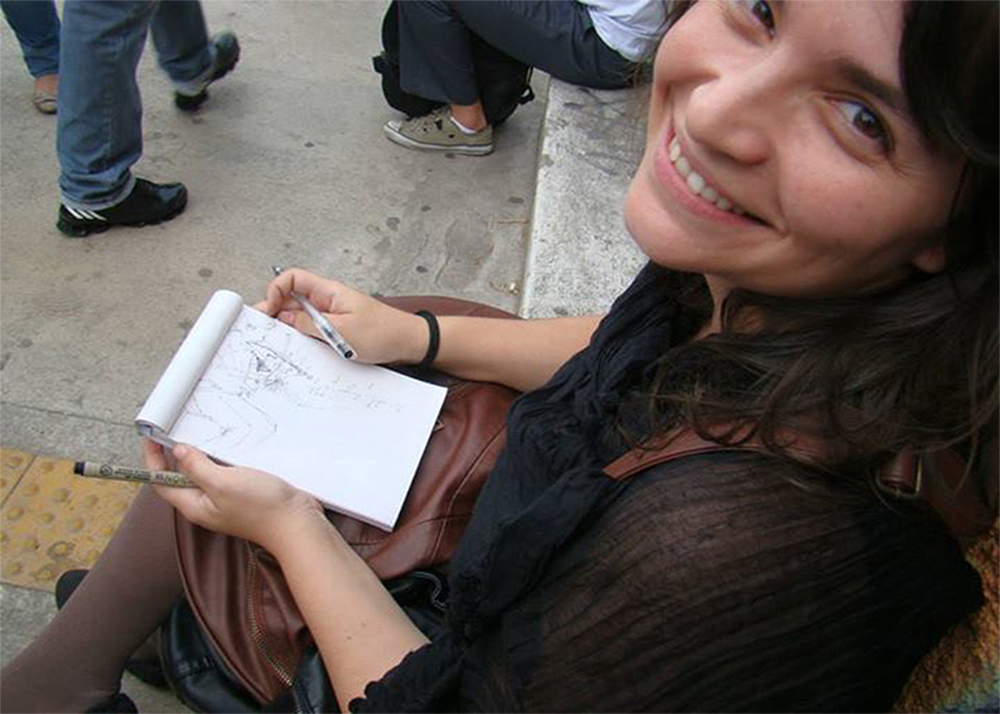

There are others, but these were the most inspiring to me personally and to my work (both academic and professional). In Brazil, I was focusing first and foremost in my academic work, so I did fewer comics, but I was doing a lot of urban sketching. In the beginning, everyone pointed out that I had a “European style” which was always a funny comment to a European. While there, and I think because of the whole experience of living in Brazil, my drawings changed in a way that I can’t really explain. The speed, the colors, and the shapes became more lively and more complex than before and the authors I just mentioned became my source of constant inspiration, and continue to be so.

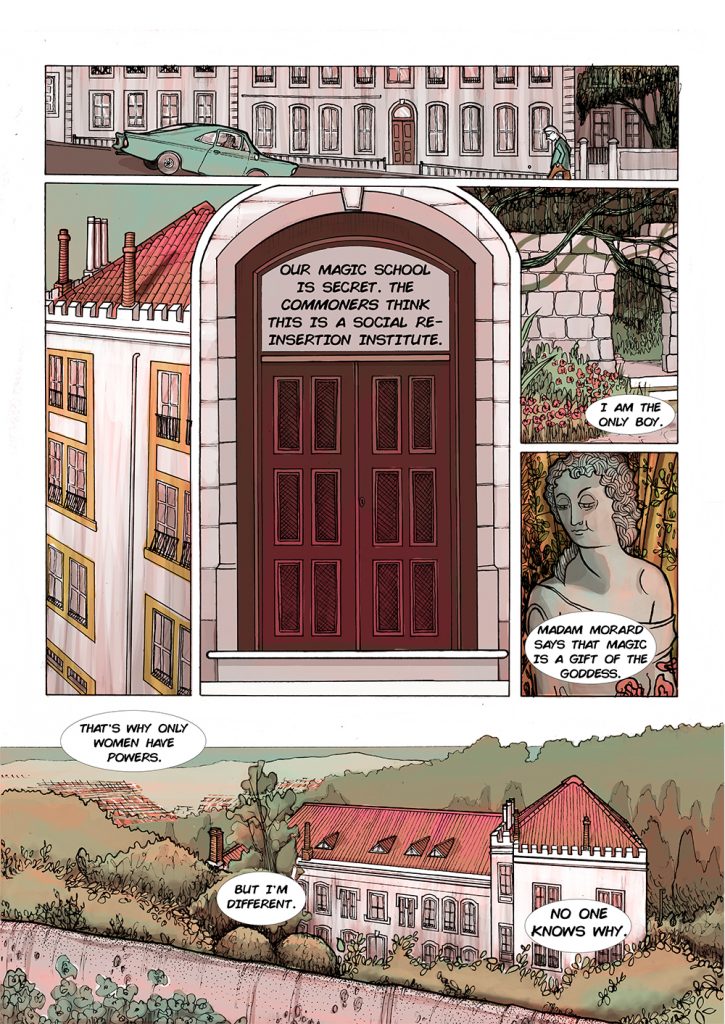

[NB]: You have worked on comics comics, as it were. It seems you’ve collaborated with a few writers for that work, such as Joana Varanda and Sérgio Santos. Could you speak a little bit about those projects and the process of working with writers?

[TAC]: Sure! I moved to the Netherlands and I was working as an illustrator (this was around the time I was awarded for the Worldwide Picturebook Illustration Competition, in 2015) and I did some work with the writer West Givner here in Rotterdam. Things were going well, but I got really sick with an autoimmune illness, so I had to stop everything. I was in the hospital for a couple of days and had to stay home for almost five months until they found the right medication and dosage for me.

At that time, I was feeling really depressed, and I don’t remember how I got in contact with Sérgio Santos and eventually collaborated with him as an illustrator for H-Alt Magazine. I do remember that the whole concept of the magazine really appealed to me since the idea was to create something out of a collaboration with others. I always had trouble creating cohesive stories, so, for me, it was a great opportunity.

After seeing my work at H-Alt, Joana contacted me. The funny thing is that we had already met before in Lisbon because she’s my younger brother’s friend. We started to collaborate and it is always a pleasure to read her stories and to develop them visually. It is really interesting to me that working with both of them really changed the way in which I construct a comic. They give me a script (Sérgio usually gives me a simple script and Joana’s scripts have a division of scenes or pages and very elaborate descriptions of the storyworld she’s envisioning), and I just go from there, constantly talking with the writers about the ideas for the narrative’s flow and design.

In a way, they give me the script and we develop it further together. Especially when I work with Joana, we always try to make the process circular. I get inspired by her script and send my ideas to her and, in turn, she sees new or different things in the drawings which make her rework the text. That’s the method we used for Gandarinha and The Hole in the Stone. This method has worked pretty well so far for me, and it also gives some confidence to the writers that the project we are producing together is close to their vision. I also had the pleasure of doing a small collaboration with Brazilian author Pedro Cirne de Albuquerque. He was developing a comic book with the illustrator Mário César called Púrpura (Portuguese for purple) inspired by his grandmother’s illness (but not about it) which was, by coincidence, the same illness as mine! After talking with him, I did a symbolic one-page illustration reflecting on how I lived with the illness. When I was sick, I felt that I couldn’t really create something new, but I kept in mind that Frida Kahlo had to paint in her bed in conditions far worse than mine.

Collaborating with these writers, at that point in my life, really helped me get over my health problems and regain confidence in my work. I believe that working with others (in collaboration with writers and other artists) gives me more confidence to experiment with the comic format. I am always in the process of developing my work and getting better, which requires having other people looking at it with fresh and critical eyes.

[NB]: Your visual style is quite different in the comics comics. Actually, you’ve employed quite a few different visual styles and codes for all your types of projects. Have you become an artistic chameleon on purpose, or do you see yourself settling on one style at some point?

[TAC]: This is actually related to my previous answer. I develop the style of the comic depending on the content of the script and tone of the story. For that reason, they tend to vary a lot. I really enjoy experimenting with styles and materials. It’s something I usually discuss with the writer and I believe that each story asks for a particular style. In the beginning, I felt that I had to draw in a specific style so I would copy other artists’ drawings, but since I started to draw more and more from observation in my professional work and experimenting with other formats such as picture books, I started to become more invested in discovering what works better for a story.

I was, once upon a time, stuck in a style when I was reading too much manga and it stopped being fun. It seemed like everything I created looked the same. I had a teacher in my architecture course that used to tell me that if creative work stops being fun then you should change it. I think that creating architecture and creating illustration has a similar creative process in that way. It needs a lot of trial and error and there is a lot of sketching involved. Since I am classically trained in drawing, whenever I get “stuck” now in some kind of style, I tend to go back to drawing from real life for a while and I search for new artists and different sources of inspiration (not only in illustration but fine art, sculpture, cinema, photography or something entirely different like gardening).

I don’t really see myself settling at a particular style. I believe that my practice and therefore my style is a reflection of where I am (physically and mentally) at the moment. You can see it is my drawing, especially if you look at the architecture. I think the trace of the pencil/pen/brush is also distinct to everyone, like handwriting, so there are similarities between my various illustrations, but style is something that I learned not to worry too much about. I think I have embraced experimentation fully in that sense.

[NB]: There’s quite a big difference producing work while being unable to leave your bed/house, and this very public process you are focusing on currently, producing work as a pedestrian. Did your current practice come about as some sort of reaction against your period being bed-bound, or was this something you were doing already?

[TAC]: That is a very good question! I don’t think I ever looked at it from that perspective. Before I was sick I was already an enthusiastic city sketcher, it was just something that grew from my architectural drawing class and simply evolved as a relaxing way to pass the time and to connect with others, especially when I started to meet up with the Urban Sketchers in Lisbon. But thinking about it now and comparing these two periods, before getting sick and afterwards, the approach I was taking to the method of drawing in the streets was completely different.

Before, I was focusing on drawing buildings mostly, and in Rio de Janeiro what I found most interesting was the way in which people moved and interacted around the streets. Although the idea of my own interaction in this process was already in the back of my mind, it was not something that I was considering to be very important. I always tried to be as invisible as I could. Being unable to leave the house at that period made me more interested in interacting with the people in the streets and in making myself part of the whole experience. It’s simply something you can’t do when being home, and this need to be more present might be a reflection of my time bedbound. I was also reading a lot of graphic journalism at that time which made me more interested in this type of more in-depth drawing reportage, by contrast to urban sketching, which can be more detached.

[NB]: Who are the “Urban Sketchers” in Lisbon?

[TAC]: It is very hard to pinpoint who the Urban Sketchers are because it is not a fixed group, people come and go. It works as a movement. The Urban Sketchers is a global movement propelled by Gabriel Campanario around 2006. People meet to draw in different cities, share their knowledge with others and share their drawings through the website. Eduardo Salaviza, who sadly passed away last year, was the great driving force behind this movement in Portugal. He was investigating sketchbooks – or graphic journals (diários gráficos in Portuguese) – and I first came to know the movement through his books when I was still in Architecture School. I have never asked this directly, this is only my opinion, but I always thought that the movement evolved naturally in Lisbon. It is a common artistic practice to draw in the streets.

To come together as a group to draw together and to follow the USk movement (which has ten commandments) would be a very natural step. Artists such as Salaviza, Richard Câmara, José Louro, and João Catarino were active within the group, assembling official meetings and creating monthly themes to keep people engaged with the practice of drawing, and encouraging us all to share experiences and results with each other. The goal is to draw the world one drawing at a time. Artists from all backgrounds and levels started to join official and unofficial meetings.

Nowadays, I can’t say who’s actively involved in creating and proposing the meetings because it is a very flexible process and it depends on the region. You have meetings of all sizes, from the global symposium to national meetings and local smaller groups of neighbors in different cities who like to draw. I have been to some meetings in different locations in Portugal, some in Brazil, and some here in the Netherlands. Personally, what is great about these meetings, besides the pleasure of getting to know the city through drawing, is the support you feel from the group. Sometimes it is rather difficult to draw in the street for variable reasons (insecurity or shyness, for example), or you feel stuck in your practice. To draw together and to share your knowledge and insecurities with others gives one motivation to keep going and reassurance that you are not alone. It also makes for unexpected encounters with others (human and non-human alike) and interesting stories. Although in my academic work I felt the need to drift away from the Urban Sketchers practice, their methods are still a very important part of how I conduct my artistic practice and, whenever I can, I still join them for a day out, sketching.

[NB]: Before we talk about your work specifically, could you outline a little bit the relationship between comics and architecture and urban space, as you see, both at a personal level, but also as you understand it through your academic work?

[TAC]: Ok, this is a difficult question and depends on the perspective of who’s answering it.

Personally, it makes perfect sense to me to dwell on the relationship between comics, architecture, and urban space. It is just something that evolved naturally from enjoying drawing architecture in the streets. I like to discover all the little architectural details through drawing, and I started to pay more attention to the rhythms and habits of our everyday life in the city because of the practice of drawing. It was curious to me how our urban everyday life can be influenced by the architect or urban planner and how we go with it or resist their plans. I find that by using the medium specificities of comics, it is easier to describe all of these curiosities and entanglements. Looking at the number of examples that we have of comic book artists who also dwell on these questions, I think that the city (its architecture, moods, its people, and so on) is an attractive topic to explore.

In terms of academic work, it is not such a straightforward answer. It’s something that I am still reflecting on. I see their relationship as being circular, they all influence each other at some point, and the most important keywords are communication and understanding. For the sake of simplicity, let’s divide two different approaches to the relationship between architecture, urban space, and comics.

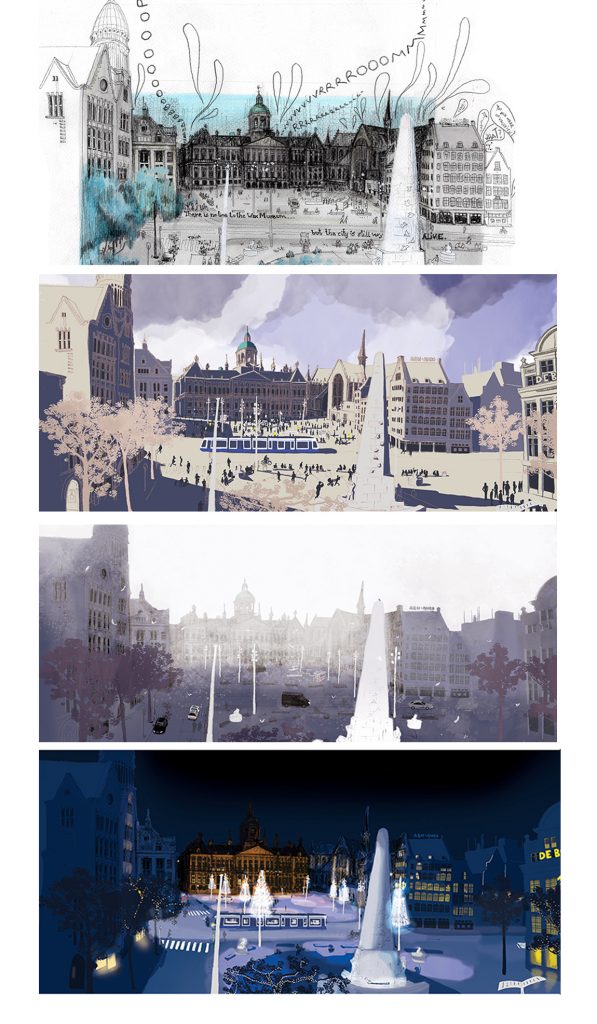

On the one hand, drawing in the streets allows one to collect all the different stories and rhythms in one’s surroundings. The time it takes to draw compels one to be present and to interact not only with urban space and architecture but with people, animals, the weather, and so on. Due to its characteristics, the drawing practice eases one’s understanding of that place as a learning skill. It really needs all of one’s attention. Drawing is a more attentive way to observe. As I said before, the use of comic elements in these drawings helps to collect all the complexities of place because one can juxtapose visual elements, create sequences to describe a path, explore stories through characters’ dialogues and through the sounds of the city, play with what is happening in the present, and, simultaneously, reflect on the past or future. It is also a more sensitive way to explore urban issues and offers a different perspective due to its subjective nature while also trying to depict real spaces, peoples, and problems. In the specific case of my work, the use of the comics practice allows me to collect elements from all my senses in a straightforward way, even if the result is a complex illustration. The aim is not to create a proper guide or a map but to get lost in all the layers that compose urban space. Of course, depending on the illustrator, you will have different goals and there are a lot of examples of city illustration and comics used in marketing and city-branding that tend to simplify and pinpoint specific elements of the city according to what they are communicating.

On the other hand, and thinking especially in the field of architecture and urban planning, many architects use the comics medium to explore their own projects as they are working on them or to disclose them. For some professionals, the use of comics is a helpful and flexible way to communicate concepts, details, or thoughts at different stages of a project. Comics also gives one freedom to explore complex architectural or urban concepts and fundamental project elements (such as light, warmth, activity, time, materiality) that are more difficult to express in a technical drawing. Here, comics works as an experimental ground for the project where you can test out all the different possibilities in a simple way and before BIM (building information modeling) stages. In architecture school, we learn how to use quick sketches or croquis to develop our projects, but if you build a comic storyworld it becomes easier to think about the liveability of that place and not only the architectural object. I suggest taking a look at Melanie van der Hoorn’s book Bricks & Balloons: Architecture in Comic-Strip Form. She has a very comprehensible study just about how the medium is used in the field of architecture.

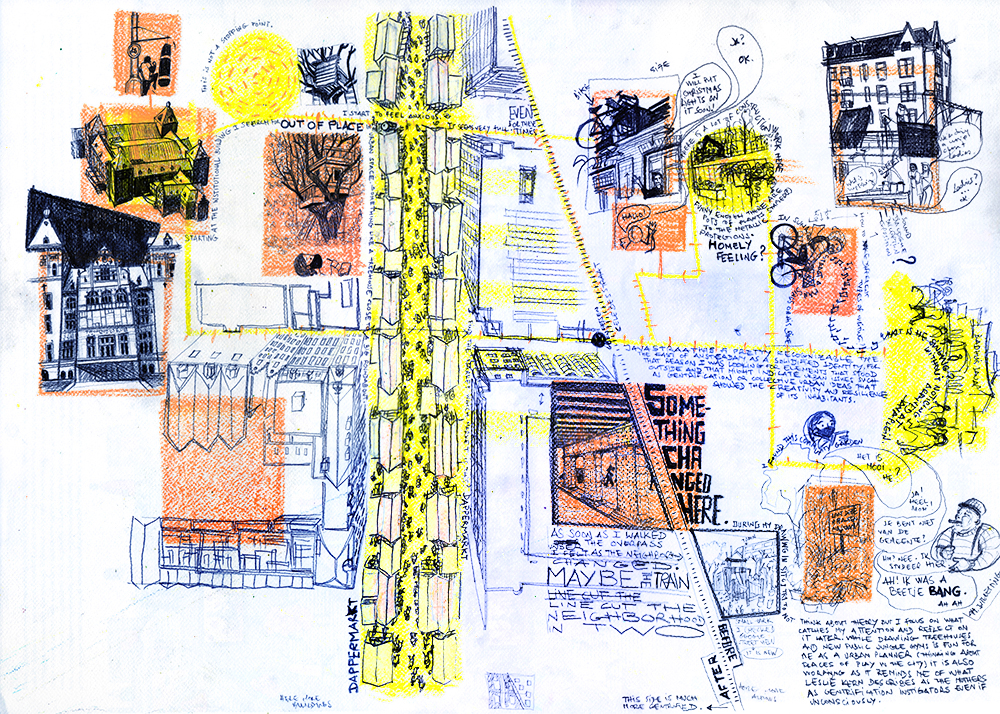

[NB]: You’re currently completing a PhD using your illustration skills, bringing comics and urban illustration together in these really exciting and complex collages. I know you’re inspired by Mitch Miller’s dialectograms project. Could you talk a bit about your thesis question, the work you’re producing now, and dialectograms as a genre of drawing (one which borrows heavily from comics comics)?

[TAC]: Well… I have the feeling that my thesis’ questions shift every time I review them, but I’ll talk about them as I go through your other question. My PhD project is the progression of my Master’s dissertation: Urban Chronicles: Representation and Critique of the City through Graphic Novels. I was fascinated with how the city was the main character in many of the comics that I read, and I wanted to know if this could be interesting for architectural and urban practices. By 2014, when I was finishing my MA, I came across Mitch Miller’s dialectograms. I felt like dialectograms are key to understanding the value of illustration, and comics more specifically, to the fields of sociology, architecture, and urban studies.

Although it is not comics per se, the practice borrows heavily from comics, as well as bringing architectural drawings, diagrams with stories, and annotations into one big illustration piece. This is the reason why I am not sure I can call the dialectogram a genre of drawing. But, for sure, it is its ambiguity or resistance to definition, in my perspective, that makes it so very interesting.

Miller generates knowledge about a place through his combinations of drawings reflecting on the people who inhabit it, about the issues that plague it, and so on. He uses the specificities of various mediums that better suit what he is trying to communicate rather than stick to an architectural plan, axonometric perspective, a graphic reportage, or an ordinary comic. In this way, a dialectogram illustration is a crucial communication piece adding urban and socio-cultural value to others besides the inhabitants.

Miller’s perspective greatly influenced my own. When I started my PhD project, I wanted to expand the universe of my Master’s dissertation into the field of illustration, and to be able to work at the limits between different types, to search for this ambiguity and its intrinsic value. I also noticed that unlike graphic novels and comics nowadays, illustration is still not taken very seriously by the academic world, despite having so much exploration potential as a mediator between reality and imagination. For these reasons, I formulated my thesis questions as: why and how is illustration being used to portray the city, and how can it be used to generate knowledge about the city’s complexity as well as co-produce urban imaginary?

Of course, the more I delve into the matter, the more I get further away from one definite answer and the more questions I have. The work I have been producing so far is based on the use of sketchbooks (drawn in situ) and reflects the immediate impact of the city in the practice and the dynamics of word and image in the illustration. These illustrations each feature individual combinations, depending on the specific response to urban space they are portraying. I turned to questions related to the practice itself and how an illustration can reveal the sense-based, immaterial, or invisible aspects that compose an urban life.

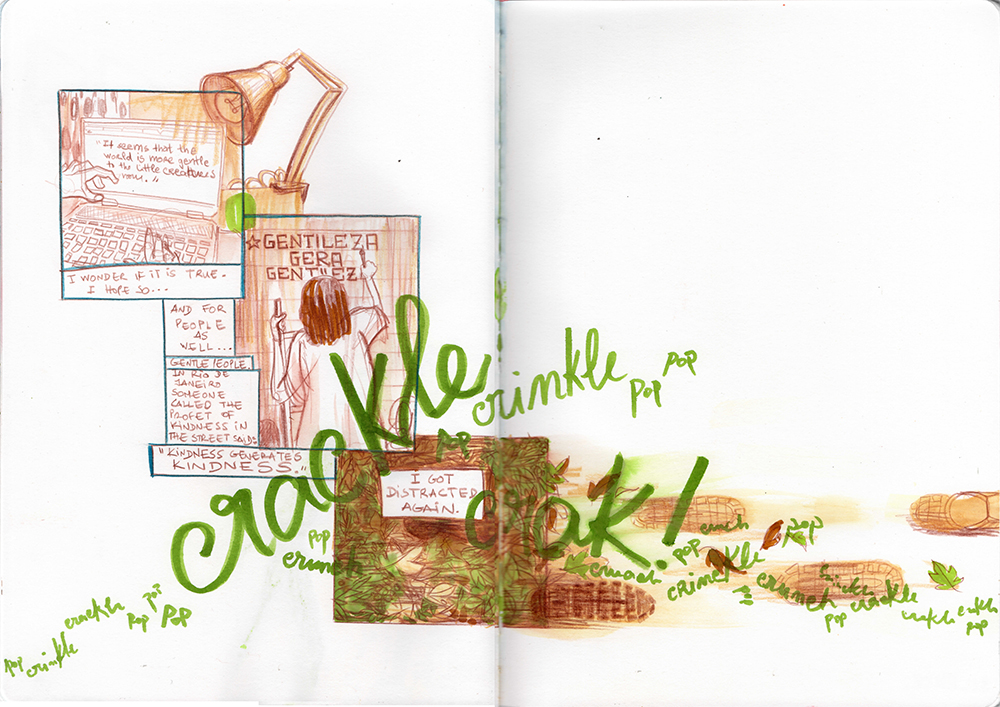

Nowadays, because I am working from home, I am focusing on how embodiment goes beyond the physical act of being present in urban space. I am reflecting on the importance of memory, incompleteness, and absence in my methodological process and on the entanglement of online and digital elements in the drawing practice. Due to being home, I am experimenting more with different formats and materialities as well. The working plan now is to investigate the limits of mapping the city through drawing and reflect on whether my artistic-practice-as-research can blur the boundaries between different types of illustration, the materiality of any given medium (book, website, etc.), and site-specific performance.

[NB]: You recently gave a lecture titled “Draw(ing) on Absence: Reimagining Urbanism in (Post)Pandemic Illustration Practice”, I’m guessing this is the working title to an article you’re writing. Could you expand on how the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns have affected the way you’ve looked at the city, and of your work and research?

[TAC]: The pandemic initially had a great impact on my research. I was focusing specifically on working with the physical embodiment and the senses in the city and it made me reevaluate certain aspects of my research that I had taken for granted. Also, people were behaving differently in the street due to the measures put in place. Looking back, I can say that I am glad for this pause and reevaluation on how to steer my artistic practice. In that regard, the lecture I gave was an opportunity to think about the challenges of this “new normal” in my practice, and to reflect on how it affected my embodiment and urban imagination.

When I am working on the illustrations, I tend to be very practical. I simply wanted to illustrate at that moment what was happening in urban space, how people were interacting in urban space through the tools that were available to me (mostly digital and online ones) without really thinking too much about it. Although it is typical for illustrators to gather their information and reference material online, it wasn’t until I started to notice some difficulties in capturing certain aspects of the city that I began to critically reflect on this shift on methodology and its consequences.

For the lecture, I gathered all the illustrations I had created until that moment (mostly on-going) and reflected on the limitations and opportunities this shift caused. I think that the pandemic gave me the push to open up how I look at the city. I was focusing on one specific perspective of embodiment and resisting the heavy influence that digital media already had on it. I concluded that I had to embrace it while considering that slowness and incompleteness will be a crucial part of the research process.

Understanding how digital media was already part of my artistic practice beforehand and how it took a step forward during the pandemic was also a very important step in my research. Besides the sort of sensitive-physical-urban exploration of my artistic practice, this was an opportunity to multiply my city gaze, which in turn diversifies how I illustrate it. Digital tools also became points of contact between the home and the urban worlds, the personal and the professional, allowing for different theorizations and possibilities in the definition of fieldwork. Working on these illustrations during the pandemic was also about imagining and reimagining the methodologies as open-ended, and through the metaphor of patchwork rather than bounded by this or that “field”. I emphasize this openness, where the illustrations have unpredictable results due to their infinite combinations.

This pandemic led me to consider the shifts in the way my artistic practice as research can move through, in and around urban environments that are simultaneously concrete (when I am present in the city) and digital (when I am absent), while I renegotiate the dynamic between research practices and their methodology. The entanglements between types of illustration, methodologies, and online and offline tools are integral to the future of my research in a multifaceted complexity that builds bridges across different systems of knowledge with the humility of knowing that my knowledge is always incomplete and in a state of permanent becoming.

[NB]: Your comments have me thinking about how representations both reflect how we see the world, but also inform our view of the world. James Baldwin wrote that “painters have often taught writers how to see.” However, who teaches painters or illustrators to see in a particular way, to discover the world through visual recreation and representation? Have you got an idea about the sort of ethical responsibilities you have when seeking to present a city on the page? About how your representations become part of the world you’re drawing?

[TAC]: Those are very interesting questions. I can’t answer the first one, I don’t know who teaches painters or illustrators to see in a particular way. Maybe it might have something to do with perception and how each person has a different way to perceive things. Tim Ingold, in Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description, claims that our perception is connected to our movement. Maybe painters and illustrators just have a certain ability or preference for translating this movement onto the page through their drawings and paintings?

About the ethical responsibilities that one needs to have when presenting the city on a page, I feel they are always in the back of my mind while I am working, but I try to not make them too present – otherwise, I would never do anything for fear that I am approaching the topic in an unethical way. However, I learned from graphic journalism that there are some points that I always need to make clear. It can be very intimate work most of “the times”, it is my body walking through the city and my personal experience. I need to make sure that the reader knows this clearly – that this is my perspective. Whenever this perspective changes or if, for example, I follow a historical approach, there will be an indication or a reference about it. I try to be as transparent and reflexive as I can in my illustration practice. I will frequently write down my thoughts on the page or draw myself in it, commenting something to make sure that the reader knows this and can distinguish feelings from facts, as it were.

Because I often work at the limits between reality and imagination, this becomes quite tricky. For that reason, I always try to be as truthful to the source as possible. This means more than drawing buildings geometrically correct. My perception of the building will dictate how I see the physical objects and the way I draw them on paper reflects my synthesis of the building (what I find more important to collect in the drawing) and visual distortions. It is all about how my body moves and apprehends space as it moves, as Ingold suggests. Drawing the processes of activity happening in urban space is not problematic even though I am drawing real people. The goal is not to accurately depict the people, but their collective rhythms and movements (which I am part of), in order to understand everyday life.

When I conduct interviews it is also straightforward. I ask permission to draw people, to use their identity, to take pictures if necessary. Maybe the person does not want to be drawn realistically because they need anonymity or the topic is sensitive. It all depends on the interaction with others and the needs of the story one wants to tell. Most of the time I just write the conversations I have in the streets as dialogue. It is possible to create a generic character to convey the idea that the conversation with a stranger happened. There is a concept called topographic or geographical character, where the character itself is already a spatial depiction because space is automatically associated with its constant relation with this character. This concept allows the illustrator to create a fictional character that is intrinsically connected to a real space and the ordinary activity in said space.

There are two ways to approach the question of how these representations become part of the world I am drawing. The first is related to a very interesting theory in psychogeography that suggests that while walking through the city the wanderer is changed. Simultaneously, in this interaction, urban space will also be changed because it was acted upon by the wanderer. The meaningful interactions in urban space that occur due to these actions can physically change the city as processes of creation are put in motion in those encounters. Following this, the illustrations become part of the world they depict as they are being made. I wonder how illustration might do more than just slightly changing some curious bystanders’ day by having a simple conversation with me, or by peaking over my shoulder to check what I am doing.

How do I put illustration into interaction with the city, and put the city in motion? For me, so far, the answer is using the illustrations (in the form of a flyer, a map, a comic, a workshop, or something else) to give agency to its inhabitants. Another way to approach this question is a practical one. The representations generally become part of the world I have drawn when they are published, distributed, and shared with others. Hopefully, the readers will be curious about the city in the illustration and will want not only to walk through the illustrated pages, reflecting on its urban issues and stories, but also to visit the place in question. We have some very cool examples of this happening already. There is a whole collection of Belgian travel books based on comics in which, for example, Brussels is presented through Schuiten and Peeters’ work in Les Cités Obscures, or Venice through Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese. Pato Lógico Publishers in Portugal have also released illustrated city maps where each illustrator draws their native or base city. Their aim is not to guide someone through the city but to share the illustrators’ favorite places and their perspective.

[NB]: One could argue that your work casts you as a flâneur. However, flânerie, in the Baudelairian tradition, has been criticized for taking the male gaze as the normative position, though I know the terms passante and flâneuse have been used to describe a female equivalent. Have you a sense as to how your “female gaze” (if you consider yourself to have such a thing) challenges, or doesn’t, this tradition?

[TAC]: This is a question I have been struggling with since the beginning of my urban explorations. and I started to reflect on it more thoroughly since the lockdown. It was when I read Deborah L. Parsons, specifically her book Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City, and Modernity, that I gained awareness of the on-going discussion regarding the flâneuse and the femme passante and their contradictions with the flâneur in terms of gaze and urban experience.

I tend to agree with Parsons’ reflection on how the contemporary flâneur can be reestablished and considered an androgynous character. Parsons suggests that the flâneur could be redefined as a metaphor for the urban observer regardless of their gender, and the act of flânerie as an androgynous act. Understood in this way, and in connection to my artistic research practice, the flâneur concept allows for the consideration of masculine and feminine gazes simultaneously, while searching for non-patriarchal tools to engage with and communicate urban space. The importance of androgyny, in this case, relates to the complexity and multiplicity of the city in itself and how one specific point of view is not enough to give it justice, to make it “the law”, how it is. There are other questions related to the flâneur as female, such as the female’s body hyper-visibility in the street in opposition to the traditionally invisible explorer. I find that in the engagement between the illustrator as urban explorer, the city, and its inhabitants, this hyper-visibility can be useful as a way to playfully work inside the visible mapped territory, to transform and subvert its order by intersecting both bottom-up and top-down. I think the question in my mind regarding the flâneur right now is how to redefine the tools I was given by my architecture background (a still very Western, male-dominated field), to question the mechanisms of power placed to regulate the city. This is something I hope to achieve through my artistic-practice-as-research.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply