“Don’t get trapped by normalcy!” This mantra, scribbled in a notebook by a young woman struggling to start a cunnilingus business, is at the core of Natsuko Ishitsuyo’s debut short story collection Magician A. The women in Ishitsuyo’s stories are different, and they know it. They’re better than their peers: smarter, more mature, more ambitious. Even when they’re pretty and popular, as they sometimes are, they’re outcasts anyway. Ishitsuyo returns repeatedly to characters who stand out from their surroundings, much as her own art stands out so forcefully from the norms of manga, both for its distinctive look and its unique thematic blend of sexuality, capitalism, and spirituality. Though these stories deal frankly with sexual experimentation and exploitation, Ishitsuyo seems just as concerned with the creative impulse, with the desire to do or make something that connects with and affects other people in powerful ways.

The English translation of Magician A (by manga scholar Jocelyne Allen) is the first publication from BDP, the publishing arm of famed Toronto bookstore The Beguiling. This edition includes an informative interview between Ishitsuyo and Allen which casts light on the artist’s biography and the origins of her distinctive style. Like her characters, she is intent on circumnavigating what’s normal, and deliberately sought an educational path outside of her comfort zone, away from Japan and other Japanese people. Inspired by Jan Svankmajer, she studied for several years in the Czech Republic, an unconventional choice, and emerged with an aesthetic that subsumes some subtle European influence into her manga roots to create a style that’s wholly her own.

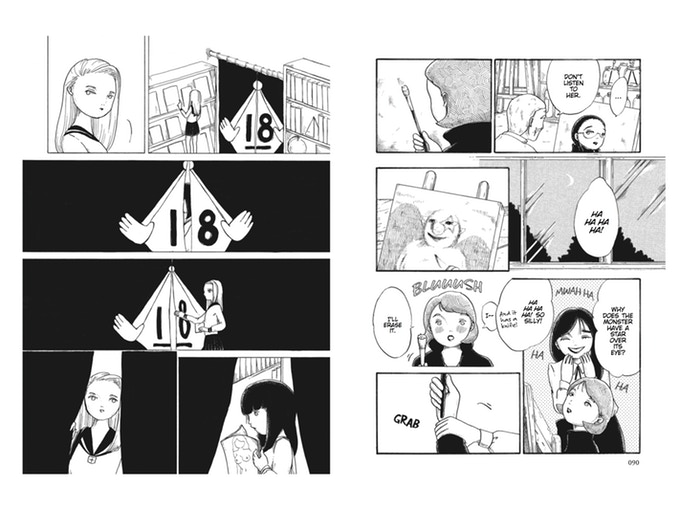

Ishitsuyo’s art has a deadpan quality that gels with the unflappable quality of her protagonists. Her characters are inscrutable and doll-like. Their eyes are tiny blank circles, revealing nothing, very different from the big expressive eyes of much mainstream manga. She often omits the details of facial features or draws things like the bridge of a nose with a frail dotted line that merely suggests the form. Clothes and backgrounds are often stippled and hatched with delicate textures, but her faces are minimalist expanses of white space with few lines marring their surface. At the most extreme, the faces are abstracted and eerie – in some panels, Ishitsuyo depicts the manipulative art teacher Ms. Mako with a single arched eyebrow, a leering smile, and no other features, while her students sometimes have no faces at all, just smooth ovals like puppets waiting to be painted.

Ishitsuyo’s writing is similarly blunt and direct but holds mysterious depths. “Art School the Mako Way,” in which two friends grapple with competing ideas about how to succeed as art students, is a prime example. After both students get into art school as they’d wanted, the story ends with the phrase, “I still don’t know what to do with this vague anxiety,” a seeming non-sequitur that actually gets to the heart of many of Ishitsuyo’s stories. Ishitsuyo’s characters long for success and often approach their activities with a ruthless capitalistic focus on building a business and making money. They’re generally successful, too, but when they achieve what they want they’re not satisfied. There’s a sense here that the constant drive for more, for success and money and acclaim, has no endpoint and, therefore, no possible satisfying resolution.

Part of that dissatisfaction can be traced to a push/pull dichotomy between creative fulfillment and success. Mako teaches that the usual accoutrements of art world success – prizes, university portfolios, art school admission – don’t matter and that artists should instead focus on expressing something about themselves. Her students are inspired, but Mako is simply using them, both sexually and as fodder for her newly formed cram school business. Her rhetoric, delivered from a position of power as a mentor and teacher, sounds like idealism but, while preaching the rejection of societal expectations, she’s really guiding her flock back towards the same old path.

These themes pop up again and again in Ishitsuyo’s stories, mutating and taking on new forms with each iteration. Illicit and transactional sexuality is a refrain in almost every story. Most of the relationships depicted in the book are exploitative and morally questionable, but the exploitation is almost taken for granted. Sexual exploitation is one of the givens, a baseline assumption of the reality that these young women must work within and around. The sex is squirmy and unsettling but never sensationalist. Instead, Ishitsuyo depicts, with disarming matter-of-factness, situations that would traditionally be given more of a moralistic or cautionary frame.

In “Kebab,” for example, the schoolgirl Erina sells herself to a middle-aged salaryman, but the sexual aspects of the exchange are beside the point. The emphasis is instead on Erina learning a capitalist lesson about maintaining the value of her goods. This current becomes even more explicit in “The Flikker,” an absurdist fable in which a middle-aged man offers an outrageous service in which schoolgirls pay him to finger them in a public park in order to release their tension. Instead of anyone being outraged or questioning this in any way, one young woman, Maria, decides to become his competitor, training a cadre of nondescript men to give head instead. The story ends with Maria, creatively driven like so many of Ishitsuyo’s protagonists, crudely diagramming ever-more elaborate sexual scenarios. In such stories, the icky sexuality functions as a gag, a way to emphasize the absurdity of the characters’ fevered pursuit of greater creative and economic successes.

In the interview at the back of the book, Ishitsuyo speaks about her own complicated feelings about sex and her general distaste for it. For her, the unflinching examination of sexual excess is a way of confronting her own indifference to such acts. Ishitsuyo draws the sex scenes very explicitly – censoring herself just slightly, leaving out certain details to skirt Japan’s strict obscenity laws – but there’s something anti-erotic about her clinical approach. In “Art School the Mako Way,” Mako’s sexual abuse of her students is presented almost like a doctor’s examination, in which she holds a mirror for the girls to look at themselves. The unreadable expressions on the characters’ faces, with their eerily staring eyes, enhance the sense of distance from these acts. The over-the-top sexuality, presented so directly and coolly, seems meant to be deliberately shocking, both to Ishitsuyo herself and her readers, but it’s ultimately just a means to an end.

The real focus of this work is on ways of thinking about success and power. Ishitsuyo’s characters navigate uneven power dynamics and sketchy situations unfazed, their blank eyes not revealing much about how they might feel about what’s happening to them. Generally, they only run afoul of their circumstances when they care too much, when they’re unable to turn off the “yuck-yuck switch” (as one character calls it) which allows them to push aside their feelings and aversions. There’s a ruthlessness to these characters that Ishitsuyo clearly sees as something to celebrate. In order to make it, to thrive as businesswomen or simply to self-actualize, they sever their attachments and block out feeling, doing anything they can to succeed. When they can’t be so ruthless, like Erina in “Kebab,” they falter and fail.

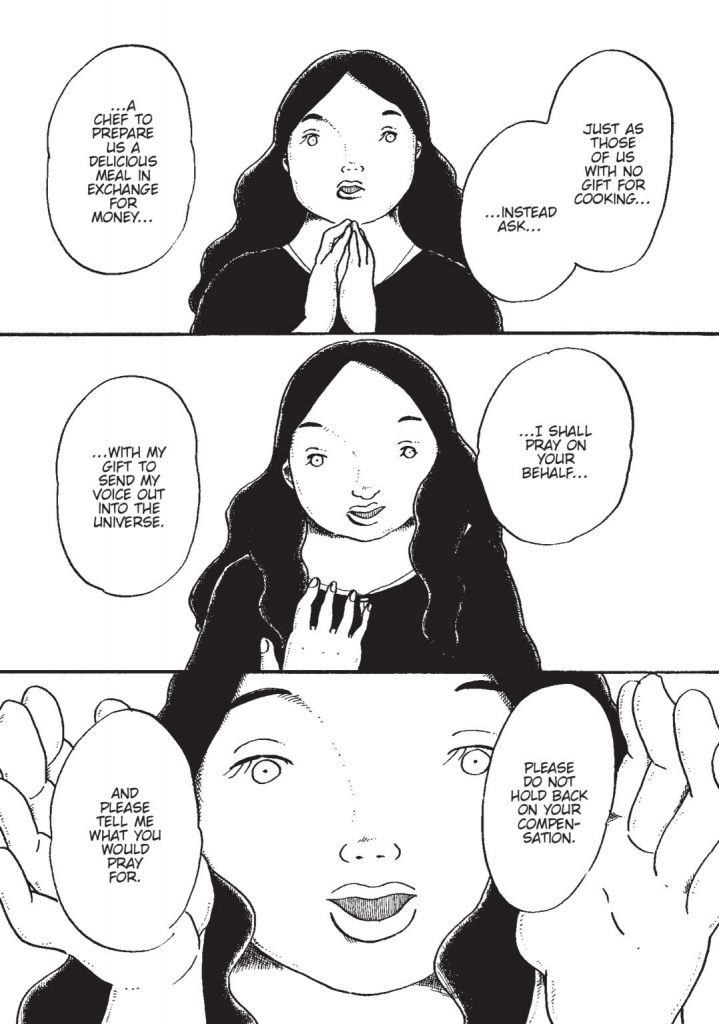

In the title story, quite possibly the best of this very strong collection, Madam Kisora makes her living by selling prayers, amassing a small cult-like group who are convinced that their prayers have a better chance of being answered when delivered through her spiritually attuned voice. Kisora couches it in explicitly mercenary terms, asking the universe to deliver “blessings in line with the compensation they have paid” for each of her adherents. Ishitsuyo is obviously fascinated by the language of self-help gurus, evangelist hucksters, and cult manipulators, but in her stories there’s magic behind such things. Self-belief is the key to unlocking that magic. When Kisora’s faith in her power is shaken by a one-sided relationship with the manipulative Meg Iriya, she loses her connection to the universe and her followers, only to amass an even larger cult once she rejects love and neediness to believe only in herself.

“Goddess,” in which Meg also appears, has a similar arc, as the popular Arisa first latches onto Meg before realizing that she can only count on herself. Maria, the heroine of “The Flikker,” uses the language of self-help (“flexible thinking,” “affirmation”) as a form of magical thinking to will herself towards success. Although the final story, an outlier from the rest, makes the magic literal, most of these stories are about the less tangible magic of words and belief, the power of language to define a reality.

Throughout all of these thematically resonant stories, Ishitsuyo maintains a surety of purpose and aesthetics that mirrors the confidence she imbues into her characters. Especially for a debut collection, this is a remarkably cohesive and complex work that addresses difficult-to-articulate ideas with wit and intellect. Ishitsuyo’s women have a lot in common, but she sets them apart from one another with distinctive character designs. Despite the blank eyes and stiff poses that make her art feel a bit chilly and austere, these characters do have personality, from Mako’s conspiratorial smile to the way Kisora’s mouth gapes wide in a roar as she shouts her prayers to the universe from her apartment’s balcony. The reserved quality of the art belies the intensity of the emotions stirred up by Ishitsuyo’s stories. The general restraint makes it all the more striking when Ishitsuyo suddenly zooms in for a discomfiting emotional closeup, but even when she maintains her distance it’s impossible to ignore just how deeply felt these stories are. The characters may be good at tamping down their emotions, locking everything behind their pinprick eyes, but Ishitsuyo expertly plumbs what’s hidden underneath.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply