Ever since Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula re-invented the concept of the vampire, his creation became one of the most iconic figures in pop culture. Throughout the decades the novel has been adapted, to varying degrees of fidelity, into every single medium you could conceive of, usually several times over. Movies, comics, TV shows, video games, operas… the trend started strong and early, with a play directed by Stoker himself in 1897 (it played once, and nobody seemed to like it very much). Now, when I say “adapted” I am being very broad with my definition — what is being adapted often isn’t the novel itself, but its title character. Everybody knows Dracula, the vampire count, but fewer could name Mina Harker, Arthur Holmwood, Quincy Morris, or Jack Seward. Dracula became bigger than the novel that birthed him, bigger than his author. In some ways, Dracula seems to predate comic book superheroes – a figure greater than any single narrative or medium, one that is easily adaptable, in the broadness of the concept (rather than its depth), not just to different fictions but to the needs of the author. That’s what Dracula is as a character: malleable. He can be whatever you need him to be. Though always (in theory) a figure of terror, he became different types of terror. Just as the character in the book could change into mist or beast, so could he change to fit the zeitgeist.

In Stoker’s novel, Dracula was the scary foreigner, the stranger with strange costumes coming to the proper English shores and corrupting proper English ladies. In Nosferatu (1922), he was something more primal, a spreading disease consuming and rotting everything around him (unsurprising, coming from a nation trying to stand up after the devastation of World War I). Dracula (1931) played up the tragic angle, the fear of being attracted to monsters, the seduction of evil. And so on and so forth, though thousands of incarnations.

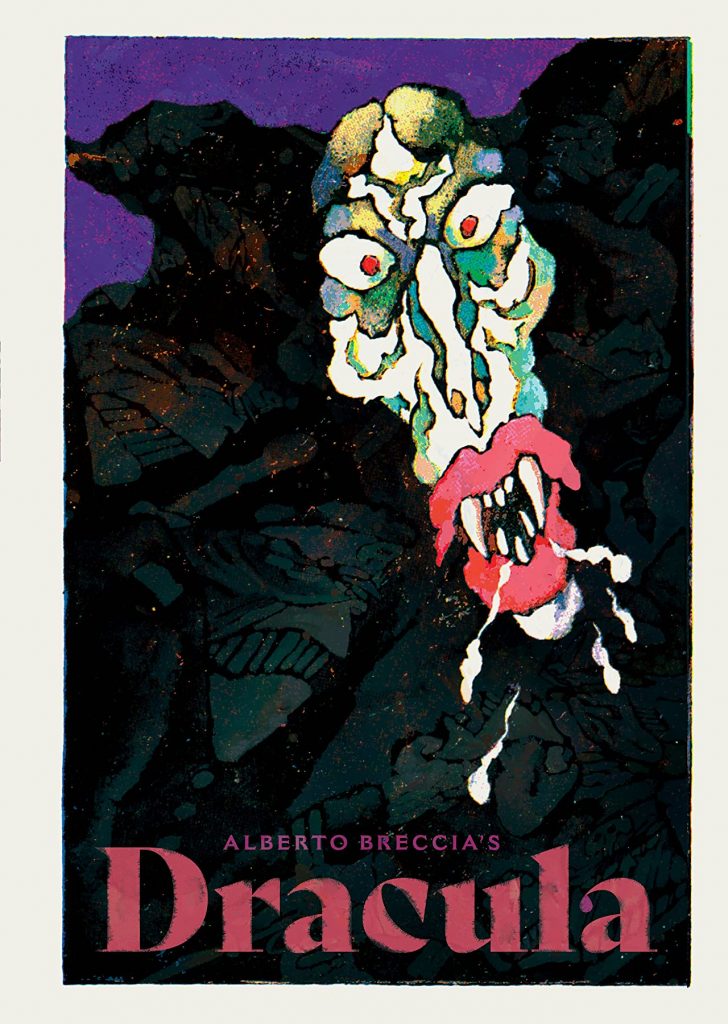

The latest of these incarnations, at least in the English-speaking world, is a new translation of Alberto Breccia’s Dracula stories. It’s a particularly slim volume, thickened a bit by some process work, a forward, and an afterword. “Translation” might be too strong of a word here, considering that this is a silent narrative, besides some signs and graffiti in the background of several pages. To call it a quick read would be an understatement. All of this might cause some to hesitate; they shouldn’t. When it comes to Breccia, every page is a treasure.

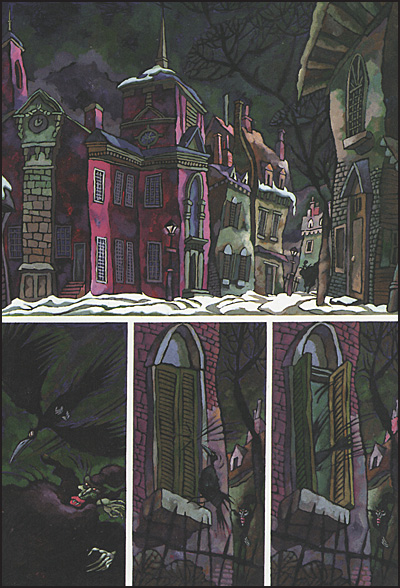

In several short scenarios, taking the vampire count from the carnival to the doctor’s office to dark back alleys, Breccia gives his vision of terror. Breccia’s world is one in which the old monster has long been supplanted. His Dracula can still occasionally muster the strength to play the beast – but most of the time he appears weary and beaten; the world has passed him over and invented newer, bigger, more elegant monsters, ones that dress in finery and can sit in polite society.

What these new monsters can do, though, Dracula cannot even imagine, as shown in the most blatantly political story in the collection “I Was Legend” – in which the count gets a chance to see the military oppression in Argentina, with soldiers lining dissidents against the wall, generals grinning with shark teeth, and people shooting drugs in the streets. The final scene, which shows Dracula joining a convent and praying to a statue of Jesus, is bleakly hilarious. Breccia was writing and drawing this as his country was going through (another) coup when suspicion and paranoia were high. He was putting a target on his own back. It didn’t stop him.

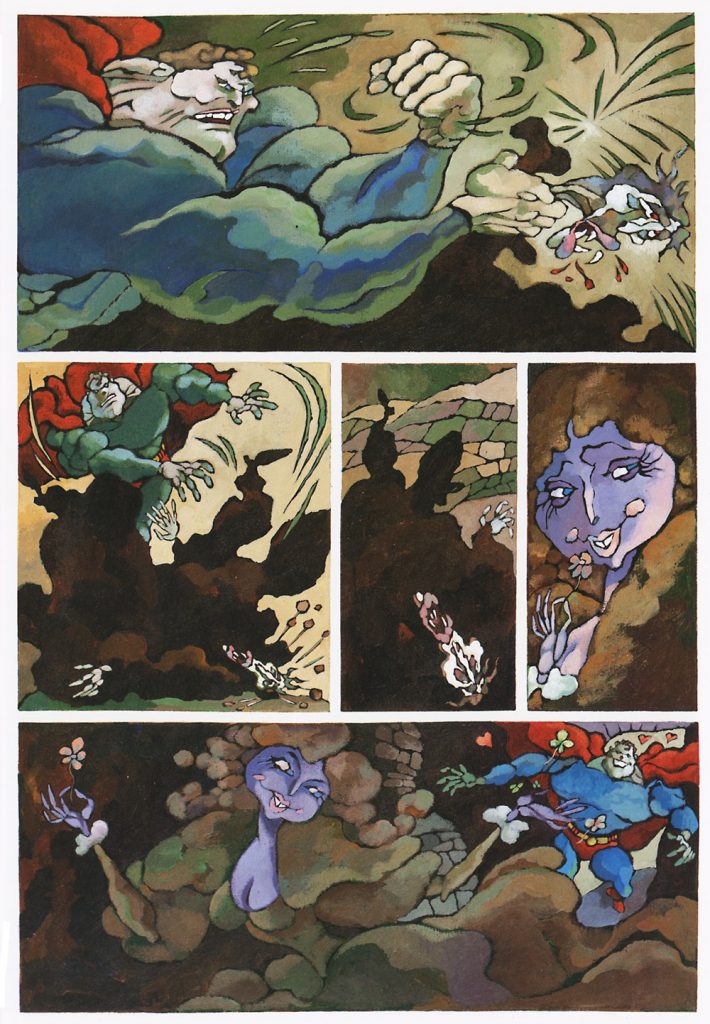

It’s also beautiful. Of course it is, it’s Breccia! While personally, I prefer his black and white work, especially the dark shadows of Mort Cinder, he proves himself easily adaptable with the new style — washed colors and figures whose bodies and faces appeared to be molded in clay. Everything these figures do has a certain heft to it, a heaviness that the world has put on their shoulders and refused to let go of. Dracula, once a mighty conqueror, now appears tired. He can “fake” his past glory, as seen in a page in the third story “Tender and Broken Heart,” which shows him posing dramatically with a wolf standing beneath his feet. It’s as bold and dramatic a portrait of a vampire as you would ever find in graphic fiction — yet this is mere puffery, as a few pages later we see him in bed, small and thin, as if the slightest gust of wind would blow him apart. It’s a grotesque world from the first panel to the last. We don’t need to see these figures doing anything in particular to understand what these stories are about.

These stories bring to mind one of the particular qualities of Breccia, which is his adaptability and his fluidity. He was truly a master of different styles and different modes of expression. While you can usually identify a Breccia page with a glance (the lighting and faces give it away) he never became a prisoner of his own stylization. And this is fitting for a story about the ultimate adapter, the 20th century’s biggest monster icon, finding out just how much things have changed. Breccia moves effortlessly between comedy and horror (or rather, the horror of becoming comedy – of being a punchline), constantly on the prowl himself.

The allegory isn’t limited to just one story. “I Was Legend” has one panel featuring a soup kitchen with a poster for Coca-Cola hung on the wall in sheer mockery. This is what the people will get, even if this is not what they need – they will learn to want it. Seeing this, my mind went back to the phrase “taking the soup;” some English Protestant societies would set up their soup kitchens in Ireland during the great famine of the 19th century, but the condition for getting the soup was to accept Protestantism. Of course, part of the cause of the Great Famine was the social policies of the English, making the whole process doubly sinister. In the works of Breccia, the United States looms in the same manner – so big as to be invisible, the threat that looms over Dracula (and other monsters). That Coca-Cola sign is one of the rare testimonies to its existence in local politics throughout the book.

What else can you make of the first story in which Dracula, on the prowl during a carnival, almost sinks his teeth into a young woman before a Superman figure, chest as wide as a refrigerator on its side and muscles almost bursting from his skintight costume, interjects? Is this meta-commentary on the domination of American comics? Unlikely. Breccia doesn’t appear the type to care about such things (his sights were on larger social issues), but the imagery is still there. That cultural domination is all part of the same great system of soft power, the presence that invades every open space and transforms it into a copy of itself.

Likewise, the final page of that story has the Superman figure dead after all, though by a different set of teeth than Dracula’s. The empire won’t last forever. Every monster finds a bigger one eventually. Alberto Breccia’s Dracula isn’t the final word on the vampire count, and I doubt we will see one within our lifetimes. But almost forty years after its original publication, it remains as powerful as it ever was.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply