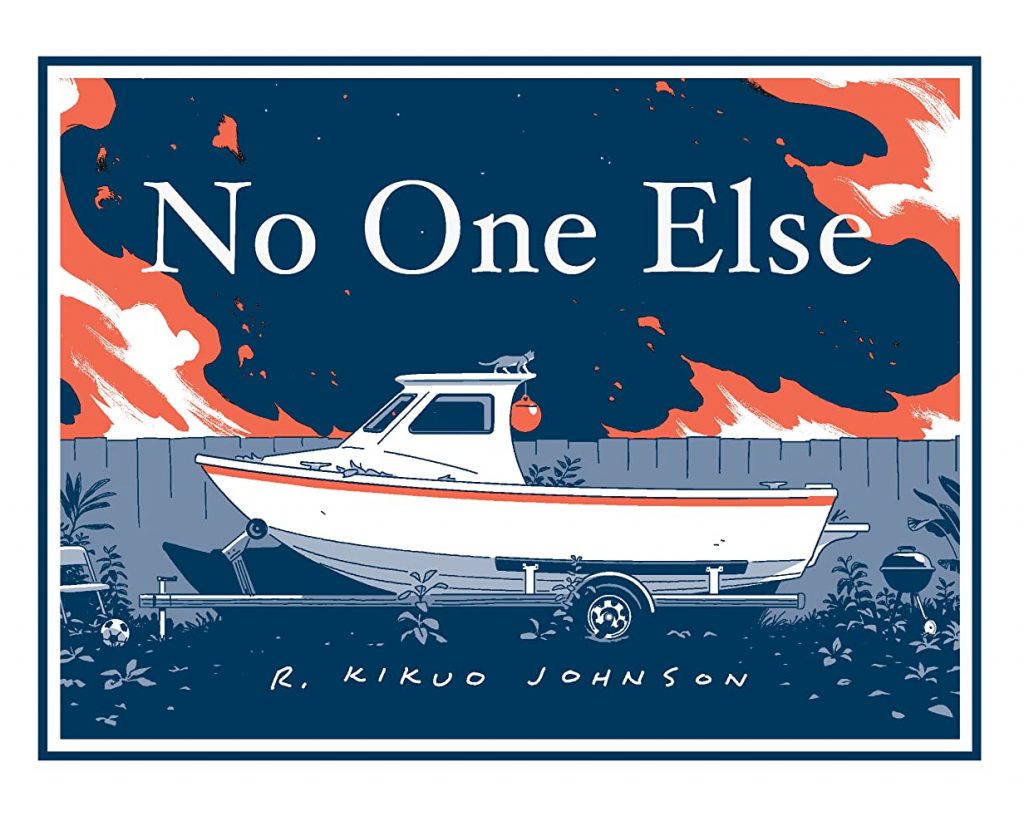

In late 2021, Fantagraphics published R. Kikuo Johnson’s third graphic novel, NO ONE ELSE, a slim volume that details the lives of a family from Hawai’i which becomes unsettled with a tragic fall. Johnson is well known for his commercial illustration work, and this release harnesses the tight compositions of his celebrated New Yorker covers with a two-toned tale of grief, family dysfunction, and reconciliation.

Daniel and I often come to the same conclusions about a book, coming at it from very different perspectives, and his recent miniature review in the SOLRAD Newsletter was cause for me to dredge the book up from the bottom of my to-read pile. I found NO ONE ELSE to be a masterful if understated narrative, and Daniel invited me to a critic’s conversation about the book. What follows this introduction is that conversation — Enjoy!

Alex Hoffman: Daniel, the first thing you said about No One Else is that you read it, and then immediately read it again. Tell me a bit about your reaction to the work, and what made it an instant re-read.

Daniel Elkin: It has to be the nuance of the storytelling. Johnson does an amazing job of letting the interactions of the characters unfold the narrative. He drops us right into a pivotal moment in a long history and, through the quiet intensity of just having these (basically) three individuals pass through it, with all of their previous damage, their aspirations, and their wills, he lets it unfurl. He then layers on top of this the culture at large and its challenges. It’s a soft boil – the rawness and intensity are all on display, but it is a whisper, not a shout.

Johnson does this masterfully, fully in control of the mechanics of comics. Each moment is fraught and deserves at least a second (if not third or fourth) look.

Alex Hoffman: I think it’s true that No One Else succeeds largely because it starts in media res. The reader is left to connect the dots of the past and sort out why each character does what they do. Johnson is trusting his audience to figure things out as they read, to find the brokenness of his cast, and to examine the ways in which the characters react to grief.

Daniel Elkin: I always appreciate it when an artist trusts their audience. No One Else demands an attentive read to unearth all of its gifts. So often, in stories of this type, the creator goes hamfisted, pummeling the emotional beats. Here, Johnson goes for the supple touch and, because of that, the interaction between the art and the onlooker becomes more intimate in the quiet. And this intimacy makes everything all that more commanding.

Alex Hoffman: It seems to me like you’re referencing some specific creators — who is coming to mind (perhaps disfavorably?) when you read R. Kikuo Johnson’s comics?

Daniel Elkin: You’re trying to get me to do some shitposting, aren’t you, Alex? Shame on you.

Alex Hoffman: Shame, shame! But…

Daniel Elkin: But… it is on me as I DID mention Adrian Tomine in the thing I wrote for the newsletter. So I guess I’ll expand on that just a little.

Johnson’s cartooning reminded me a bit of Tomine in terms of line and his use of negative space. What I like about Johnson as compared to Tomine, though, is that Johnson feels no compunction to make the interior, exterior. Johnson trusts his audience to understand. He trusts us to read the thoughts and motivations of his characters through their actions and their interactions. Unlike Tomine, who has the occasional habit of telling not showing, Johnson’s world is more authentic. It feels lived in, not lived by. The audience understands and empathizes with the individuals because there is an authenticity to how they move in the world.

Alex Hoffman: I think you bring up the obvious correlation between the two authors, which is their line is quite similar. While I would note that No One Else looks substantially different from Night Fisher, Kikuo Johnson’s 2005 book, Tomine’s work has solidified around a specific style for the last decade or so, and No One Else seems to drift towards that style. It’s clean, almost ligne claire, and it makes the drawing quite pleasant to look at. There’s also the comparison of subject matter — people living their lives and dealing with the vagaries of time, bad luck, and malfeasance.

While I’m not sure that I’m right about this, I think the thing that truly separates Tomine’s recent work from the work of Kikuo Johnson can best be summed up in a single word: cruelty. Tomine’s humor, his perception of the world, has this tendency to be myopic and therefore drives towards cruelty, either self-inflicted or otherwise. Johnson avoids it entirely. The lives of the characters in No One Else are hard, no doubt, and there are grievances and drama, but Johnson seems far more empathetic towards his characters than Tomine. That doesn’t necessarily make one author better than the other, but during the pandemic, I’ve been less compelled by work where cruelty is its central thesis.

Daniel Elkin: Yeah, I agree. I’m much more for compassion than cruelty nowadays. Is that a result of the pandemic or just generally maturing and becoming a grown-ass man? Does that even matter? Anyway… What about you, Hoffman? What is your takeaway from No One Else?

Alex Hoffman: I think that the place you have to start with this book is trauma. I don’t think you can really dig into No One Else unless you center the pain that each of the characters is dealing with. Robbie runs away from home because of his abusive relationship with his father. This leaves Charlene to care for their father as he ages, and for almost a decade she takes care of everything for him, including food, toileting, and bathing. His dementia has led to her being stuck in one place, just struggling to make ends meet. The extended family, also aging, is of no help, and her brother Robbie is out of the country living his best life. That caregiver stress, and then the trauma of her father’s untimely death, is part of the reason she decides to shut down and hyperfocus on getting into medical school. Likewise, Robbie’s disappearance from Maui to Australia to be a performer is just as much in spite of his father as it was his own dream. Brandon is 8, going on 9, and acting like an 8-year-old, until he’s acting like a 28-year old, fighting for normalcy as everything goes to shit, and knowing in the back of his mind that his grandfather tripped and fell on his blanket, which is what started the downward spiral to begin with.

The source of all of this trauma is Charlene’s dad, in one way or another, and it is ultimately all of his broken relationships that cause the hurt and suffering throughout the book. Johnson isn’t necessarily laying blame at his feet, but the generational nature of this story is a clear and consistent focus throughout the book.

Here’s a question for you – is the cat that they bring home at the end of the book actually Batman?

Daniel Elkin: I think the answer to that depends on how you want to read the ending and how you see the theme evolving and moving forward. Is that an evasive answer? Absolutely.

Regardless of your answer, though, the last three pages of No One Else seemingly explode out of nowhere – initiating a whole different set of questions than what, I think, was going on previously. I’m kinda in the midst of working that out, though, even after what is now my sixth read of this book.

Still, this ending did draw my attention to Johnson’s careful and masterful use of the color orange in this work. The first time we see him use it (aside from the front end pages and the title page) is via a cheeseball and, then, “grandma’s quilt”. From there the orange only appears a few more times. It is the color of fire as the sugar cane fields are burned. It shows up on the beautiful two-page spread in the exact middle of the book. It is, more subtly, the color with which Jonhson infuses his flashback scenes. It is the color of the stoplight that pops the emotional and thematic beat right before what is, for all intents and purposes, the denouement of the book. Finally, No One Else ends with the orange vomited callback to the original introduction of the color via the cheeseball at the beginning of the book.

Johnson uses this color as an amazing narrative motif, and I’d like to hear your thoughts on that, Alex.

Alex Hoffman: I agree that Johnson’s use of color is masterful in this story, but I wonder what you feel it signifies? For me, I see orange as the color associated with danger, but I’m not certain that’s quite right. Sometimes a cheez poof is just a cheez poof, you know? But I think of the fire, the blanket, the stoplight – these are all extraordinarily dangerous moments. Maybe the color orange represents change; the end of an era of care, the loss of something, the finding of something?

Daniel Elkin: It seems to me that it represents those moments in life that signify change. Those little unremarked instances during the day-to-day that bring about profound consequences. It’s only in retrospect that the cause-and-effect relationship is unearthed. The fact that it is Brandon’s vomit that is orange at the end is, in this context, kinda fascinating. Especially since it harkens back, in terms of shape, with the original introduction of the catalyst (more or less) for what happens narratively.

Interestingly, if you look at the back cover of No One Else, Johnson chooses to have Brandon’s t-shirt glow with this same orange – and yet nowhere in the pages of this book is that true. With a book as meticulously thought out, paced, and presented, I’m wondering why that choice was made.

Alex Hoffman: Ultimately, Brandon is the agent of change, right? His grandfather’s fall is an accident, but he fell over the quilt that Brandon was lounging in. Perhaps it’s a stylistic choice and nothing else, but Brandon is the first domino that falls, so to speak.

I wanted to float back over to Robbie, who I think is a very interesting character, if not a very sympathetic one. It’s hard not to read Robbie as selfish and intrinsically motivated, but he also does the work of notifying some of the elders that his father has passed, and he “watches” Brandon when Charlene completely shuts him out. Robbie has this difficult relationship with the island, with the boat he cleans, with his family. He’s a complicated character. I found my opinion of him changing the most over the course of the book, and even through multiple reads. Which of the “broken adults” did you find most compelling, Daniel?

Daniel Elkin: Robbie does, in his own way, step up through the course of the book and I can easily see why you picked him out of the group.

For me, though, I feel Charlene has the most interesting arc. Charlene had the mantle of responsibility foisted upon her. She showed up when no one else would. And to do so, she sacrificed her vision of the future, her dreams for herself. She put her life on hold for the sake of others, limiting the extent of her vision of success. When given the opportunity to refocus on herself and her desires, she dives headfirst, single-mindedly, to the point of neglecting all of her responsibilities that took attention away from what she wanted – a sort of it’s now or never attitude.

Certainly, the argument could be made that she should be castigated for this neglect, especially in her duties as a mother, but I don’t see it that way. What I see is a person who has deferred their dreams for so long, that the pressure those dreams exuded exploded upon release. There is a power there that is awesome in its expression.

Here in the West, it seems to me, especially for women, we so often push forth the paradox that we admire people who are “go-getters” and laud that drive to succeed, while at the same time expecting individuals (again, especially women) to participate in community and family. So much of what we see celebrated in mass media is that success hustle – it’s almost like it’s one of the basic tenets of Capitalism – just as often as we see individuals chastised for “not playing well with others” – we laud the prowess of the individual, but cringe when they beat their own chest in triumph.

Johnson does a great job in No One Else of threading the needle when it comes to Charlene. He plays the light-handed presenter, forcing the reader to examine their own preconceptions. Charlene is nothing more than who she is, and Johnson brings out everything that is human about her.

Alex Hoffman: I think that’s a smart read of the character, and of the various economic and societal factors that affect the family throughout the story, although I would push you harder and say that Charlene is expected to care for her ailing father. Robbie ran off because he expected Charlene to take care of their dad in his old age. Working in medicine, I can tell you that caregiving of this intensity is extraordinarily difficult, and it often takes a village to make it work. The fact that Charlene is expected to do it by herself is partially why her father passes away like he does. And isn’t it interesting that, professionally, Charlene is a nurse, a profession that is primarily identified with caregiving? It’s clear that Johnson is interrogating this aspect of Western culture, but as you said, it’s with a light touch. There’s no moralizing or hamhandedness in this book.

Daniel Elkin: And, again, as I alluded to at the start of our conversation, that is one of the things that I really like about this book.

I guess I have one more question for you, Alex. How much of this book is about cleaning up? Johnson has the act of making and “tidying” messes sprinkled throughout No One Else. Do you think that this is what we should take from this book? That life is a process of cleaning up the mess other people make? Or is there some other theme you think is dominant?

Alex Hoffman: That’s a tough question to answer. I think it’s not just “cleaning up the messes that other people make” but rather that life has this cyclical motion of accumulation and winnowing. But who does the accumulating, and who does the winnowing isn’t always expected, or known. A resonant theme these days.

Daniel Elkin: To everything turn turn turn – I am large, I contain multitudes – so we beat on, boats against the current. Stuff like that, right?

Alex Hoffman: Exactly.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply