“After one long season of waiting, after one long season of wanting, I am breaking open; my insides are pink and raw, and it hurts me when I move my jaw, but I am taking tiny steps forward”: these are the first lines of the Mountain Goats song Absolute Lithops Effect—the first song I listened to in the weeks after my father died. The reason I listened to this song of all songs is more banal (less clichéd, my inner cynic is tempted to say) than one might expect—not because I thought its message might hold some magic power over my personal, recently-shaken reality, but because the podcast I Only Listen to the Mountain Goats had recently published an episode on it and I hadn’t gotten a chance to listen to it because it happened to be released on the day my father died—but, coincidental and minute as these circumstances may be, they didn’t stop this song from entering the personal mythology of my life, of grief and life around it (not so much overcoming it but learning to treat it as a sort of metaphysical roommate).

It’s an interesting thing, that personal mythology—everyone tends to accrue one of those, if only because it leaves one no choice but to accrue it; it forces you to grow it by way of forcing one to grow around it. It’s not as straightforward as your standard mythology, part-etiological and part-eschatological, being made up of objects and anecdotes which don’t really seem to come together into any all-encompassing message or revelation beyond the circumstantial, but it bears every bit of impact that traditional myths do, or perhaps even more than that; after all, the scale of Gods and Creation and Eschaton makes it easy for you to lose yourself in, but the scale of the personal is tiny, atomic—and it doesn’t take much more than atoms to create a devastating bomb.

The secret of this impact and its intensity lies in how hermetic it is: as is only appropriate, it is purely internal, existing in the deepest reaches of your emotion, forged in the most intimate process of semiosis. It screams out in its uniqueness, refusing to be understood and even more explosive when someone presumes to understand it nonetheless; true, everyone bears it, but no two are alike. A prism of mediation, then, can only emerge from the chaos of the hyper-specific, from the details you can’t imagine anyone replicating, in all of their elegant awkwardness and awkward elegance; it can only emerge from the things that can be signified, but never truly named.

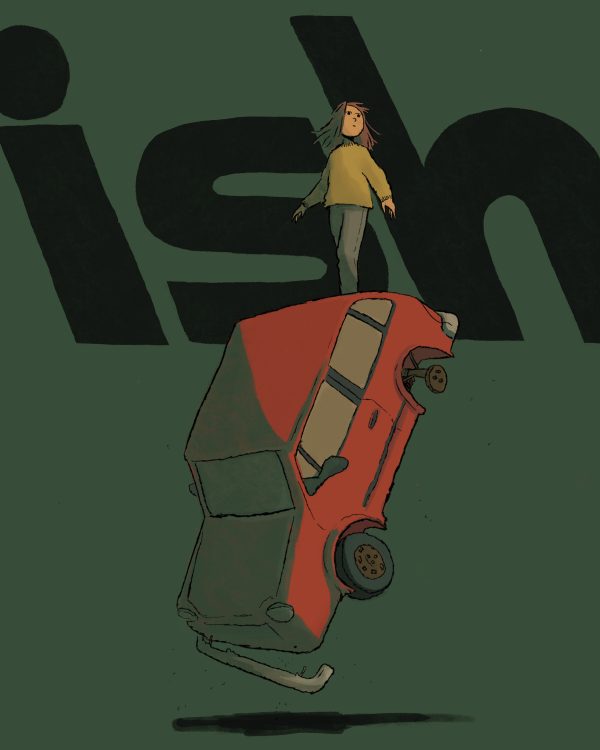

Adam de Souza’s comic collection ish, published by Silver Sprocket in April 2022, is precisely such a prism: presenting a selection of vignettes (some straightforward-narrative comics, some graphic poems, some illustrations) that have something to do with the themes related to grief and life alongside it, it never aspires to depict What Grieving Feels Like, nor does it even attempt a direct memoiresque approach; it is a roundabout thing, a performance of the delicate dance of the indirect. In one of the pieces, de Souza (or his narratorial stand-in) recognizes, textually and explicitly, that it cannot properly convey feeling, only the recollection thereof:

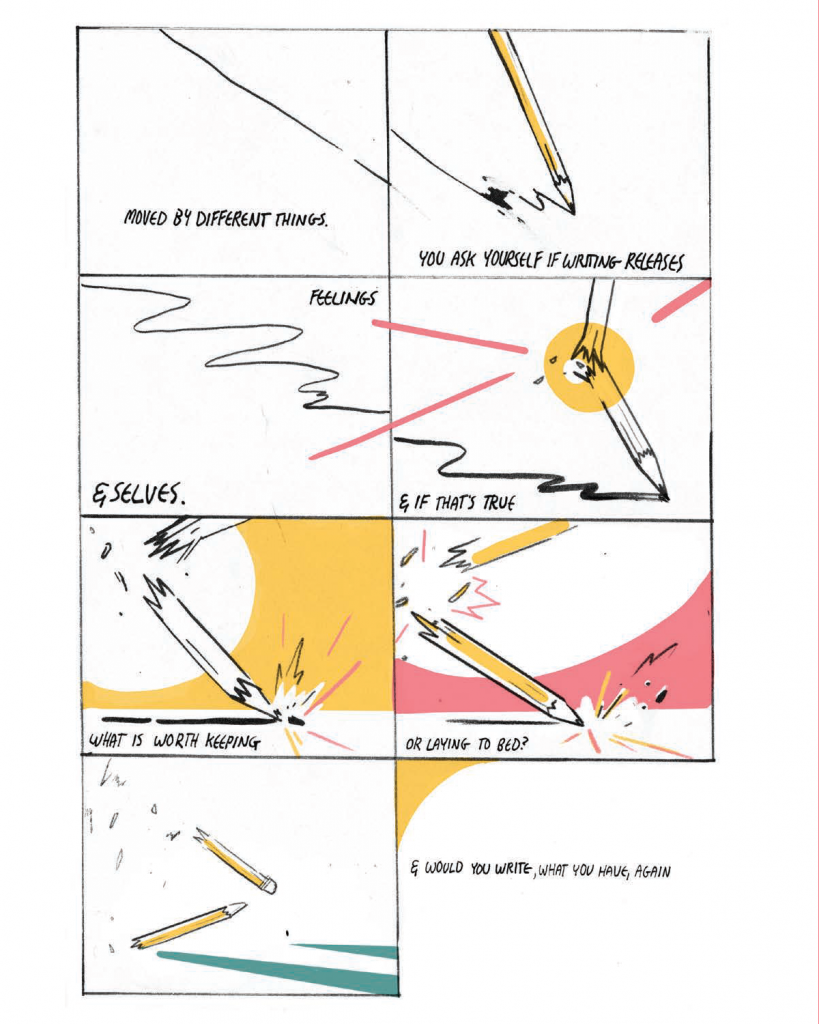

“You write a story about a song that moved you,” he writes in one of two pieces originally printed in the zine and so you write it down, “How it made you feel / weightless / flooded / a bit of everything / but now that you hear it / & though it’s the same / (the piano lifts) / (the drums nip) / (the bass plods) / you no longer feel it. / & you imagine yourself / standing / or floating above / watching someone / writing those specific words / about vague thoughts / on feelings brought on by a song. / That someone is moved / but you sit unfeeling.”

The piece goes on for a a bit after that, but the message is clear: recollection is a treacherous act. Divided up into two parts, the word literally means “collect again,” but can you truly re-create any collection? Is re-creation not the greatest lie? Your attempt at the articulation of emotion will only stray away from what you are trying to say, a simulacrum thinking itself a source. That’s the problem with language: a word thinks that it is a universe but is not even a world; you will forever be chasing the fullness of what you are trying to say, the fullness of what you are feeling, but your best chance of actually approaching that fullness is by examining your point from every possible framing you can think of, shifting perspectives and methods of delivery. The cartoonist, or his stand-in, has made his peace with this: “And isn’t acting and recalling an act of praise?” asks the narrator in the other piece originally printed in that same zine, after recognizing the infidelity brought on by recollection.

Part of the beauty of ish stems from precisely that point; de Souza shifts his formal and narrative approaches with every piece, seeking the overlaps between those ever-diverging experiences, meaningful in their fleeting nature, forever opening themselves up to those who know how to look. Taken as a whole, the comic collection takes an approach I can only describe as pure form, forever reexamining the tools and methods it took for granted and willing, even eager, to replace them with something new that does a better job at driving home what the work is trying to say.

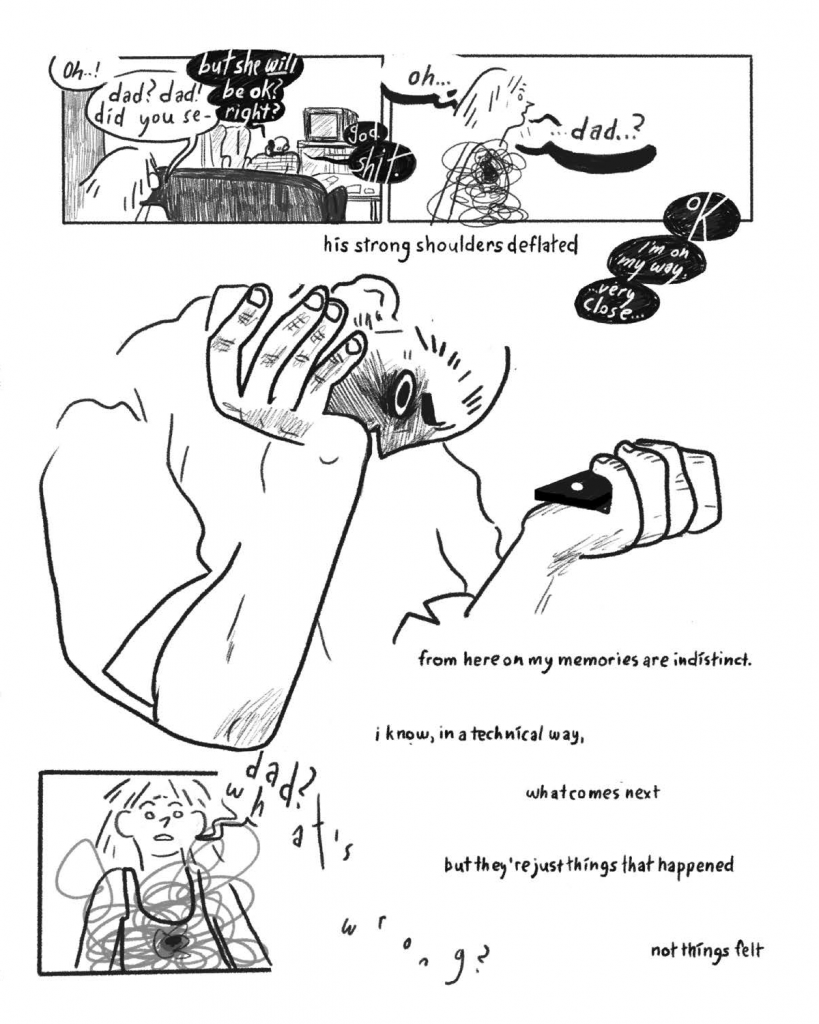

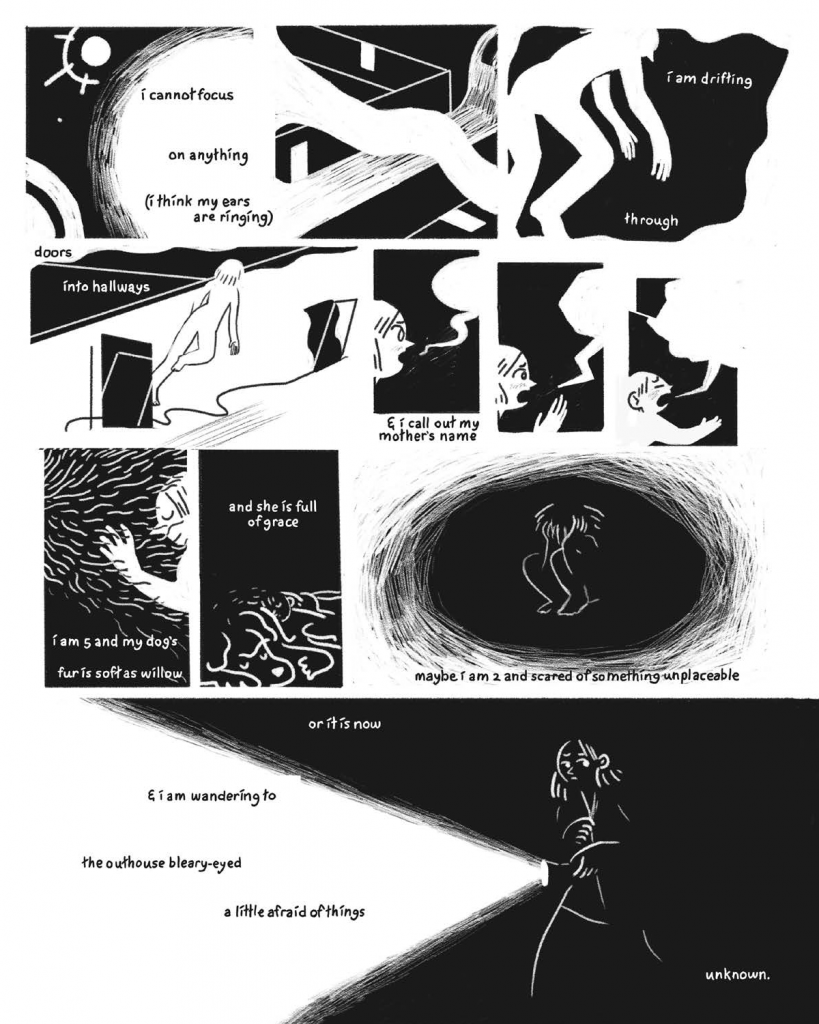

Perhaps the easiest thing to notice about the collection is its visual fluidity: the first story, about the a-touch-too-distant relationship between a father and his teenage child in the moments leading up to the news of the sudden death of the mother of the family, is depicted with lines of black ink and largely uniform weight with some occasional graphite-grey texturing and shading; its characters are simplified (their outlines or details often omitted) and reminiscent at times of Michael Furler’s cartooning work, its environments and furnishings appear only where necessary, and the layouts are frenetic, as panel borders are often done away with and never set on any sort of grid, unafraid of leaving large swaths of page-space completely empty. Later stories and vignettes share the same rendering sensibilities but opt for the addition of color, or are more amenable to the employment of a fixed panel grid, depending on what suits the piece in question. By the time the book arrives at its final coda, the texture of the line shifts, taking on the crisp brusqueness of de Souza’s ongoing webcomic Blind Alley. Unlike Blind Alley, however, this final piece is in color and is not set on the serial’s two-by-two grid, instead opting for that freewheeling approach to the space of the page that often does away with panel borders completely, allowing scenes and images to melt into the presence of one another, or otherwise keeps the panel borders but only occupies a portion of the page, letting it breathe and pause as necessary.

One choice I find particularly interesting is the way de Souza ties together three of the longer pieces in the collection: the eponymous story -ish, an untitled story in the middle of the book about a deprivation tank-like experience, and the closing piece all feature the same protagonist, a femme-perceived person whose mother died in a car accident. The connections between the stories are subtle, mostly hinging on the repetition of imagery (the black spherical stone that uncoils into an amorphous snake-like creature which appears in all three pieces, and the image of a crashing car that is depicted or mentioned in two stories, as well as in one illustration and on the cover of the book), as if to say that the interconnectedness is optional, tentative. This is further achieved by the relative blankness of the character: the details we know about their life are anecdotal, and we don’t get their name. Through the omission of detail, de Souza almost emphasizes that they are not so much a character as they are a vessel meant to explore and flesh out this cluster of emotion and idea relating to the central themes of the book; by prioritizing the fleshing-out of emotion over narrative event and circumstance, he then manages to amplify that aforementioned universality of the hyper-specific.

Interestingly, even though it deals with the same characters, and though it is the most thoroughly-rendered piece on a visual level, coda breaks away from the directly-narrative approach of its two narrative antecedents, mediating between them and the approach of the other short comics in the collection. While all of the stories in ish rely heavily on narration and internal monologue, the pieces that do not comprise the core “story arc” are less story than they are graphic poetry, all dealing in some form or another with the contradictory and dual modes of grieving, with the illusion of its on-off nature. In de Souza’s depictions, the illusion is demonstrated as exactly that: grief will always make its presence felt, likened in one piece to an audience member’s cough disrupting an orchestral concert.

For a long time I struggled with reading poetry, in part because of how it is taught in school as something to chop up and dissect rather than something to actually be taken in in any manner outside of the clinical, but reading the looser pieces of ish I am reminded of the type of poetry that attracts me; de Souza’s free-verse arrhythmics continue the general tune of his gentle directness, doing away with the ornate in favor of the amplified simple, letting uncategorized emotion speak up, out of turn and unmediated. It isn’t “messy,” but it certainly does not bother with the artifice of cleaning itself up through meter and self-imposed order. Perhaps oxymoronic, the best way I can describe this approach is “a deeply-considered abandon,” an expressiveness that seeks only to express, self-sustaining and self-fulfilling.

While one can say that ish is “about grief,” that would be, in my opinion, superficial; a more accurate view of it, I think, would be that the collection is about communicating grief, and about the grief of communication itself. A recurring motif in most, if not all, of the pieces curated herein is a nigh-poststructuralist argument: post-structuralism, examining the false rigidity of the tendency toward categories in the structuralist movement that preceded it, understood that the power of language is in its mercuriality: the language that mediates between the reality you perceive and the way in which you perceive it only goes a certain length, because both the way you perceive reality and the language that you use to articulate it will be prone to bias, to error, and to that greatest sin of the objective: personality. In his collection, de Souza writes and recalls (and, in doing so, to borrow his own turn of phrase, praises) the shortcomings of communication, the multitude of signifiers and likes needed to even come close to that abstract beast of sadness that lies dreaming in one’s heart; “what I am trying to tell you is bigger than any of these words,” in de Souza’s own, well, words. It’s hard to miss how communal the works in the collection are—characters may feel lonely, but they are not alone, they hinge on their existence in the grander social scheme—and communication, in all its many forms, is what builds community. So, if the language we use is fundamentally broken, what does that mean about us, its wielders? Are we all broken, too?

The answer: a resounding yes. We’re all broken in the same ways; we’re all broken in absolutely unique ways. We’re as broken as the words we use to describe the ways in which we are broken, and that’s okay, because what else can you do but fold up this knowledge and take it into your heart? That’s the grounding element of life: the knowledge that we’re all just broken glass, anyway. Grief is the most efficient messenger of this knowledge, deftly reminding you that the only reason there’s still a rug beneath your feet is because no one has yanked it away yet. The best you can hope for, then, is not for a chance to feel whole—what does that mean, anyway, to be whole?—but to be aware enough of the points of your brokenness to be able to hold yourself together without cutting the people around you (which in itself may take some trial and painful error, as the nameless protagonist of the three core pieces subtly recognizes in the middle story). That’s the beauty of Adam de Souza’s comic collection ish: its brokenness is one that we all share, but it engages in that brokenness as a form of dance. It examines itself carefully and says: After one long season, after one long season of wanting, we all are breaking open. Our insides are pink and raw, and it hurts us when we move our jaw. But we are taking tiny steps forward.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply