If you are a long-time fan of American superhero comics, it’s likely that you often find yourself living in two parallel worlds. In one world, the regular one, the maker of all these fantastic characters that dominate our culture for over a decade now is the ever-smiling and ubiquitous Stan Lee, a man whose visage is just as famous as the fictional super-people with which he’s associated. In the other world, that of the initiated, Stan Lee plays the role of Satan, a scheming figure of mediocre talent with one major skill: leeching off the true creator of the Marvel Universe – Jack Kirby.

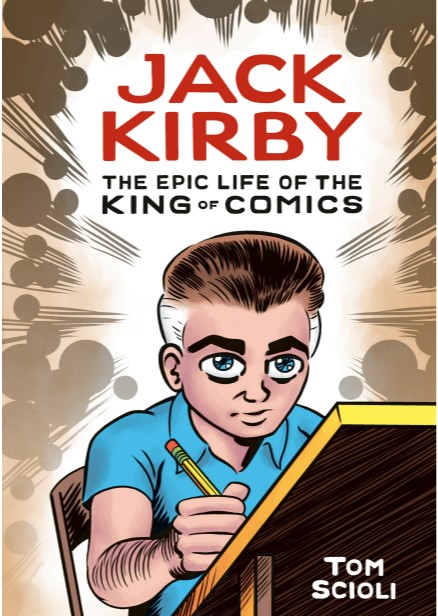

The act of writing about Kirby, as seen in texts like Kirby: King of Comics and The Jack Kirby Collector, often goes beyond a simple biographical or analytical exploration and enters into the realm of Heirography. Partly this is because the usually niche subject of comics culture tends to attract people who are already fans — if you don’t already have a positive passion for the subject, it’s unlikely the pay will attract you — and partly because the act of writing about Kirby can be seen as a corrective. The Kirby appraisers are like fish swimming against the current of accepted reality in search of the truth. While it’s a correct assertion that there can be no true impartiality in writing about history, it often seems many don’t try. Tom Scioli’s new graphic novel Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics, for example, avoids any pretense of objectivity. The whole book (with three minor digressions) is presented from Kirby’s point of view, often utilizing words said by Kirby in interviews.

The result is a story told in chronological order that is still somewhat backward-looking in its approach. We are seeing not just the version of Kirby he wanted to us to see, but also a version that attempts to justify his place in the comics canon, to claw his way back to the respect he thinks he deserves. Scioli, a true believer of a different kind, doesn’t seek to challenge Kirby. Why would he? Anyone who follows Scioli’s works knows his admiration of Kirby and any attempt at truth beyond the words of the king would be perceived as a mere pretense. So he doesn’t even try.

Sadly, sticking to Kirby’s own words means much of Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics is focused on the humdrum of contractual activities and the difficulties of working in the industry. These were the subjects that Kirby was often asked about in all the fanzines and media interviews, and thus it the most explored part of his life. While I do not doubt that there are some creators who could make these mundane parts exciting, this is not Scioli’s strength. Instead, the graphic novel sings loudest and clearest in the first third of the story. This is when we are in the world of Kirby’s childhood, immortally dramatized in Jack’s own “Street Code” story. As readers, we bear witness to the tiny child making his way, forcefully if need be, through a world that aims to do him no favors.

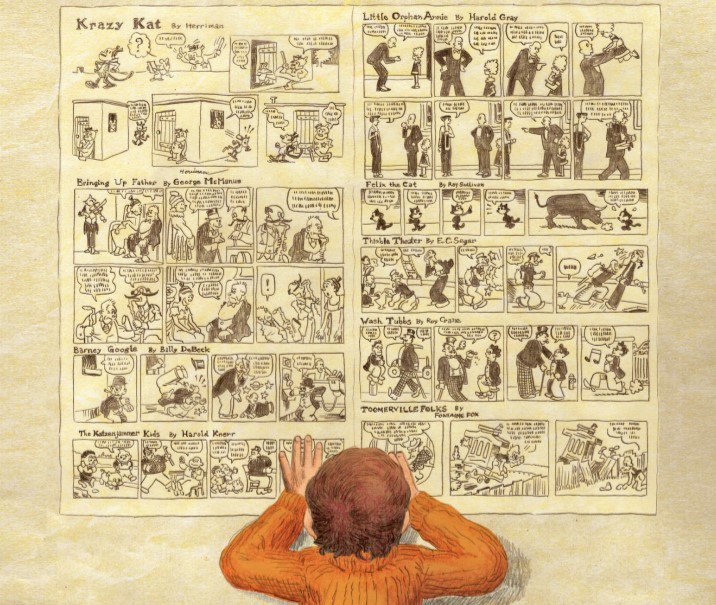

An early scene is probably the best in the book: Scioli draws a young Kirby, sprawled in front of the comics supplement of the newspaper. The paper is massive, larger than the boy (real-life Kirby was not the tallest of man and the comics plays it up, or rather down, making the protagonist’s every struggle appear even harder); focusing further, we can see that Scioli has masterfully aped several classic comics-strips from Krazy Kat to Thimble Theatre. This page shows us not the “real” world, but the world as seen through Kirby’s eyes: the paper is large because it represents the large world of comics, free of the constrictions found in the hard neighborhood or the small house. To see that masterful illustration is to understand the power of the medium in a way no caption could explain (Kirby would know, he never read what Lee put in the word balloons).

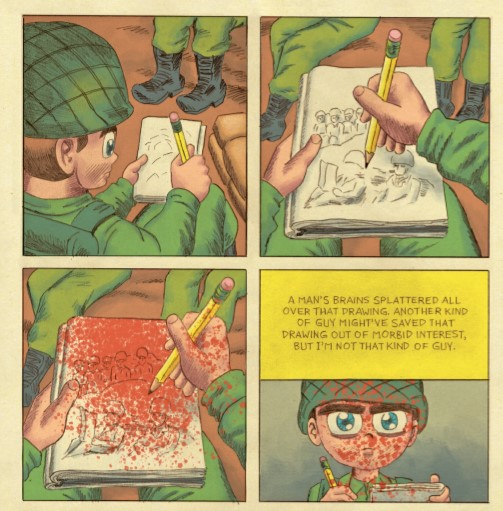

The first chunk of the book has several such moments: Child Kirby is sick in bed and opens his eyes to see rabbis seemingly hover above him, calling for the demon inside him out; a street brawl in which the boy has his head smashed into a wall (you can feel the impact); Kirby scrawling on the walls, escaping between the legs on adult (just as an older Kirby would go on to sneak his art and creativity between the legs of industry and commerce). Likewise, there are the scenes of Kirby as a soldier: the hard boy becoming a hard man. These are all drawn masterfully by Scioli, ably moving between moods (romantic, tense, fanciful) in a way that captures all that life has to offer.

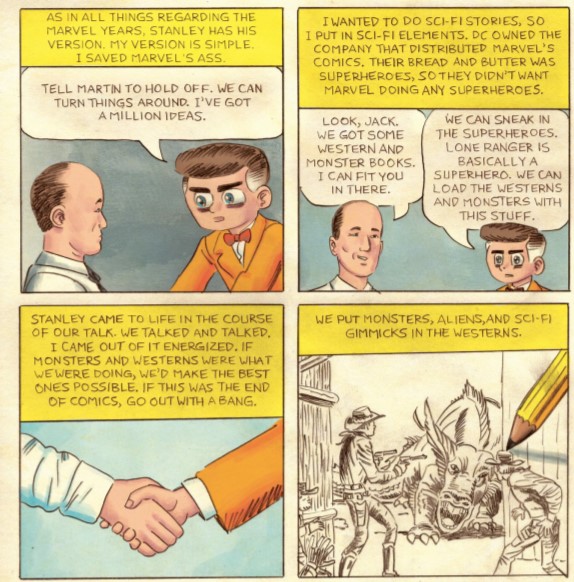

Sadly, by the time we reach the middle sections that deal with his post-war career, the book begins to stall. Perhaps stall is too harsh of a word; the graphic novel doesn’t become bad, but it lacks the elation of these early pages. It becomes a sequence of one event after another: partnerships are formed and dissolved, concepts are created and discarded, and people in management keep mistreating Kirby – taking his money, his ideas, his characters (but never his pride). It’s all kept on an even keel that makes the events feel rather repetitive. While there are ups and downs, including Kirby swearing that if he sees Lee again he’ll kill him, they lack the energy to stand out.

If you are a Kirby-aficionado you probably read about these events a dozen times over, and If you are not already invested in the business minutia of the comics industry this story is unlikely to pique your interest. In the past, Scioli’s love of Kirby shines brightly in his own projects (from Godland through Transformers vs. G.I.Joe), yet here it feels muted. Possibly it is the lack of fantastic elements, which usually allows Scioli to stretch his stylistic wings, possibly it is the large number of pages that he needs to fill. Scioli’s previous projects were much vaunted for their ability to cram so much material into a single issue (a single page even), it is far harder to keep this level of energy over 200 pages.

Still, the work has its particular strengths: the physical depiction of Kirby, small and large-eyed (constantly drinking in the world around him with his gaze), sells well his approach to life. Scioli does some lovely work with facial expressions and body language (Kirby sure loves his chocolate cake). The research work is impressive, likewise the reconstruction of older artwork. The end of Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics, which uses a quick montage to examine Kirby’s influence on popular culture, is touching. As Frank Miller says after Kirby’s death: “An age passes with Jack Kirby. There is a before Kirby and after Kirby. One age does not resemble another.”

It’s not the graphic novel that put these words in his mouth. Frank Miller said them. Surprisingly, though, despite the lack of objectivity Jack Kirby: The Epic life of the King of Comics is not heirography. The graphic novel doesn’t give one because it doesn’t need to. Kirby knew how good he was, just as the people around him did. He never needed to say he was the greatest — after all, why state the obvious?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply