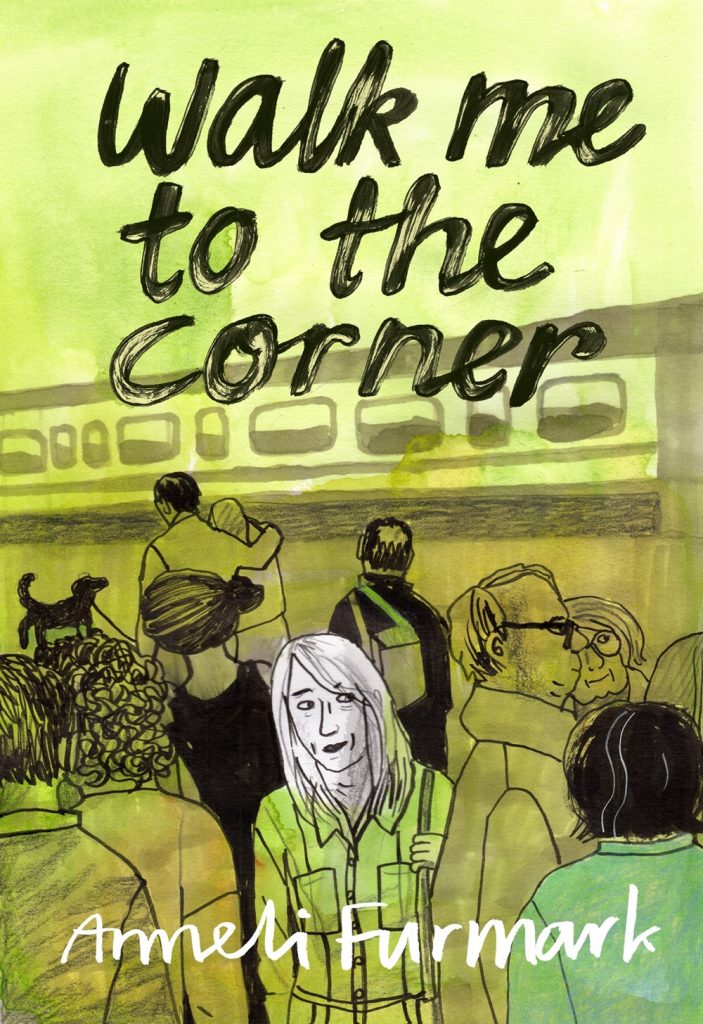

Anneli Furmark’s Walk Me to the Corner takes the well-worn trope of a passionate love that derails the main character’s life and views it through the lens of a middle-aged woman, a perspective our society regularly overlooks. Elise is married to Henrik and has two adult sons. She has a life that is perfectly fine, or even “nice,” as she and Henrik describe a swim they take together. However, while at an event, Elise meets Dagmar, a woman who is married to Ann-Charlotte, with whom she has two daughters. They begin texting, then they agree to meet, and then they fall in love. From there, not surprisingly, complications ensue, especially as they each tell their spouses what has happened and what they hope will continue to happen. Elise and Dagmar disagree on leaving those spouses and their lives in order to be together, leading to further complications, and the work ends on an ambiguous note. Cleverly, Furmark ends the work with Elise’s comparing their relationship to an amusement park that comes to life when they’re together, as Elise experiences a roller coaster of emotions.

If this graphic novel were simply an exploration of passion and love that runs up against a variety of opposing forces, it could still be interesting in and of itself. Furmark even nods to the traditional romantic storyline by including a montage of discarded clothes and referencing how often such a scene is portrayed on television. Elise was always skeptical of such a scene, but she now understands how it can and does happen. However, Furmark adds complexity by exploring a relationship between two women who have reached the mid-point of their lives. Elise tells one of her co-workers about the relationship, and he laughs about it. She tells her friends, “He couldn’t stop laughing. It was apparently the funniest thing he had heard in a while. That two mature ladies could fall so deeply in love. That was apparently very funny.” Furmark wants to dig deep into this idea of societal expectations to expose them for the ageist view of love and passion they are.

She does so by granting Elise and Dagmar the same emotions and reactions as people half their age, reminding the reader that love doesn’t fade with age, nor does the pain that comes when love isn’t requited. As Elise learns when she goes to find the perfume Dagmar wears, just to smell it, only to end up buying a bottle at $95, “being in love is expensive.” Furmark means more than the financial costs here, as their decision to try to be together, one way or another, will cost them both more than they could imagine. When Henrik and Elise were younger, they celebrated one of their anniversaries at a picnic table with a bottle of wine, ultimately carving their initials into the table. Elise is hiking near that table after she has begun a relationship with Dagmar, and she goes to look for the initials, but they’re not there. The tables have been replaced, a metaphor for all she has given up in her pursuit of a relationship with Dagmar.

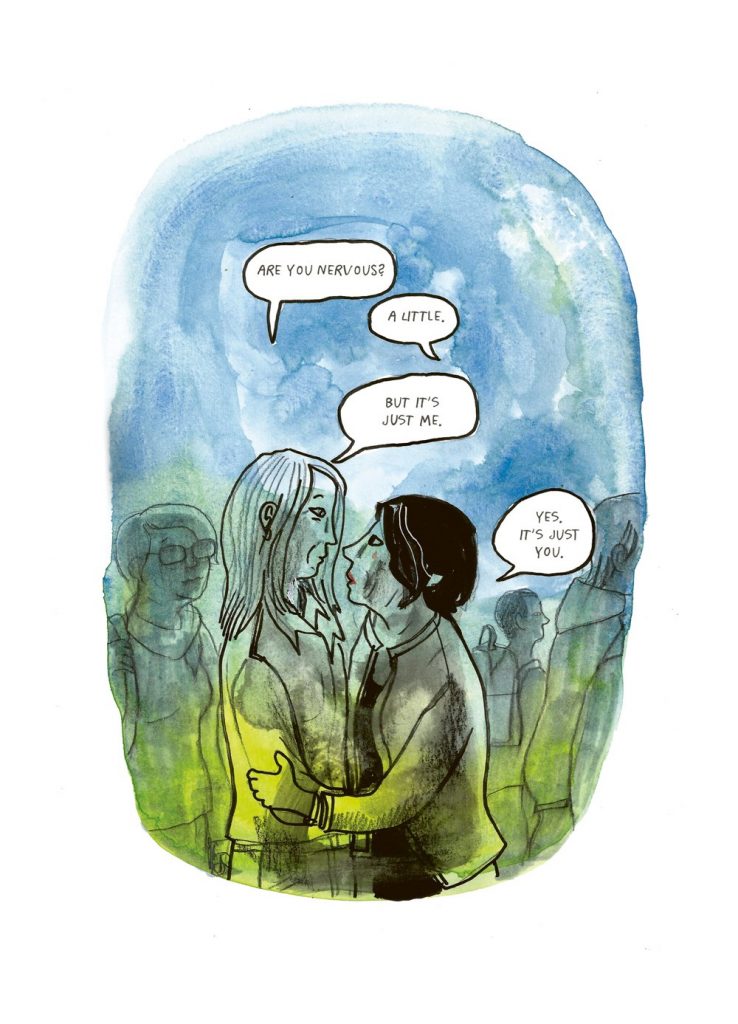

In fact, the artwork throughout the graphic novel works well to mirror some of the main scenes or ideas. Furmark forgoes traditional panels for rounded, softer pictures. That structure is echoed through the messages Elise and Dagmar send one another, as it creates the image of text bubbles within the rounded pictures, bubbles within bubbles. Furmark also uses sequences of several pages solely composed of images to convey strong emotions, especially of loss, such as when Elise lies on the floor and sobs after she relates a co-worker’s comment about how Elise could lose both Dagmar and Henrik.

Elise always had the belief, though, that she could simply hold herself together to get through difficult times, an idea that runs throughout the work. The opening page of the graphic novel, in fact, is an image of a needle and thread stitching together three patches that read “Elise had always thought that all you had to do was pull yourself together.” At this point, the reader has no idea what she has or will suffer that requires that pulling together. At the beginning of the relationship, Elise had romanticized it and similar stories, especially in comparison to “Brokeback Mountain,” the story by E. Annie Proulx that was adapted into a movie. She and Dagmar had joked about being the “Brokeback Mountain” of middle-aged women, meeting secretly with various excuses for where they were going. Late in Furmark’s work, though, Elise tells Dagmar that she has read the story again, and it’s not funny at all; it’s quite sad. She even quotes Jack Twist’s famous line: “I wish I knew how to quit you.”

Elise has found that the pain of a life where they’re not truly together outweighs the benefits they have found otherwise. As in all relationships that move toward an end, Elise begins to wish for love simply to cease, no matter how good it feels when they’re together. She thinks, as so many people have, that anyone who can figure out how to stop loving someone deserves a Nobel Prize, “in chemistry or something.” By the end of the work, she comes back to the idea of pulling herself together, but, rather than having the ability to do that, she feels she and Dagmar are in a puppet theater where the audience (and, thus, the readers of Furmark’s work) know what trouble will come from their decisions, but they are unable to resist them.

She foreshadows all of these complications through the title of her work, which comes from a Leonard Cohen song, “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye.” It’s a song about loving someone over a distance and with obstacles, and it’s unclear if the speaker and lover are saying goodbye after seeing one another or for good, a question the reader will be left with at the end of this work. Given that we see the world through Elise’s lens, it’s fitting that we don’t know how it will all end. Like Elise, we’re trying to understand how such a relationship can work, if it can at all. Like Elise, we hope the risk was worth it.

That risk is the underlying question of the work. As Elise tells a group of her friends, “We [she and Henrik] were fine. My life wasn’t bad. And now…What would you choose? To be fine all the time…Or fantastic sometimes and terribly sad sometimes? Or pretty often…” While one of her friends suggests that “fine sometimes and fantastic sometimes should be an option,” the best Elise can hope for, she says, is equilibrium. This question is the difference between this work and others on the same theme, but with a younger cast of characters. Those in their twenties aren’t supposed to worry about equilibrium; they’re supposed to want passion. Furmark points out that all of us want passion; those who are older simply want some stability to go along with it. They want more than fine; they want fine and fantastic, if only they could find a way to have both.

In talking to Felix, one of her sons, Elise talks about how movies always have the young couple, the real one, and the older, silly couple, who are the joke. Elise even believes it comes from Shakespeare. She says, “But later—when you’re older, it turns out the drama is just as big.” Furmark explores that very real drama, which is, in fact, just as big, by focusing solely on the older couple, making them the real one. The drama is just as real, and the work is all the better for that’s being the case.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply