For the first 17 years of my life, every few weeks, we (my mother, myself, and often at least some of my siblings as well) would drive up north, to a kibbutz named Ginosar, right by the Kinneret. Often we were met by many tourists who were interested in the would-be anarchist messiah who may or may not have walked the surface of those same waters some 2,000 years ago, but that’s not what we were there for. My grandmother lived there, for the last 60 years or so of her life (having been born in Austria almost a century ago, escaped to England after Kristallnacht, and, finally, come to Israel in the Fifties where she lived in different kibbutzim before settling in Ginosar), and my mother grew up there. We were city children, my siblings and I (my siblings even more so, having been born and at least partially raised in a proper city, unlike myself who was born in a not-quite-city-not-quite-town, more “sub-“ than properly “-urban”), and the two hours’ drive might as well have been two days or two years, or however long it took to arrive at a different mindset. It’s easy to compare 21st century kibbutz life to the rounded-corner image of the Small Town so romanticized by American pop culture—the kibbutz, stripped of the utopian quasi-Soviet aspirations that so characterized it in the not-too-distant past, might not have been the collectivist unit that it once was, but it certainly retained a tight-knit social aspect, and a reliance on (and consequent connection to, albeit in a way that is less romantic in ideology than strictly utilitarian) nature, that urban life has conceded in favor of dense immediacy. My mother, out of the kibbutz for over forty years, still talks in the rhythms and details of the small community, is still keyed into the goings-on in the locale and the characters in play, which, while not entirely static, remain mostly the same.

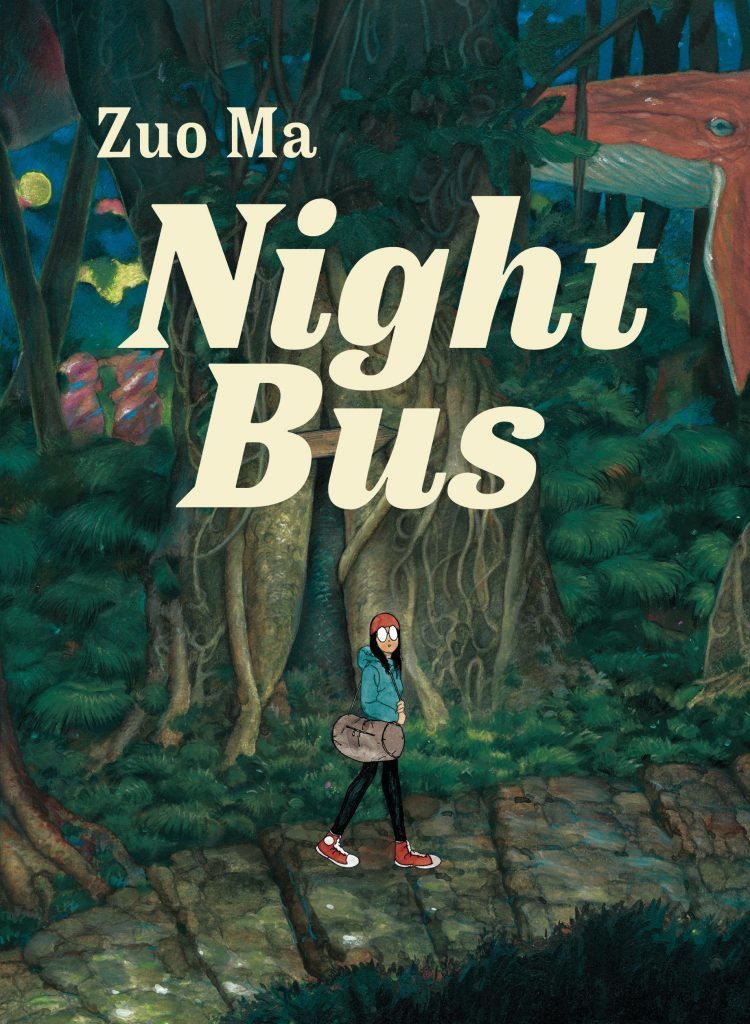

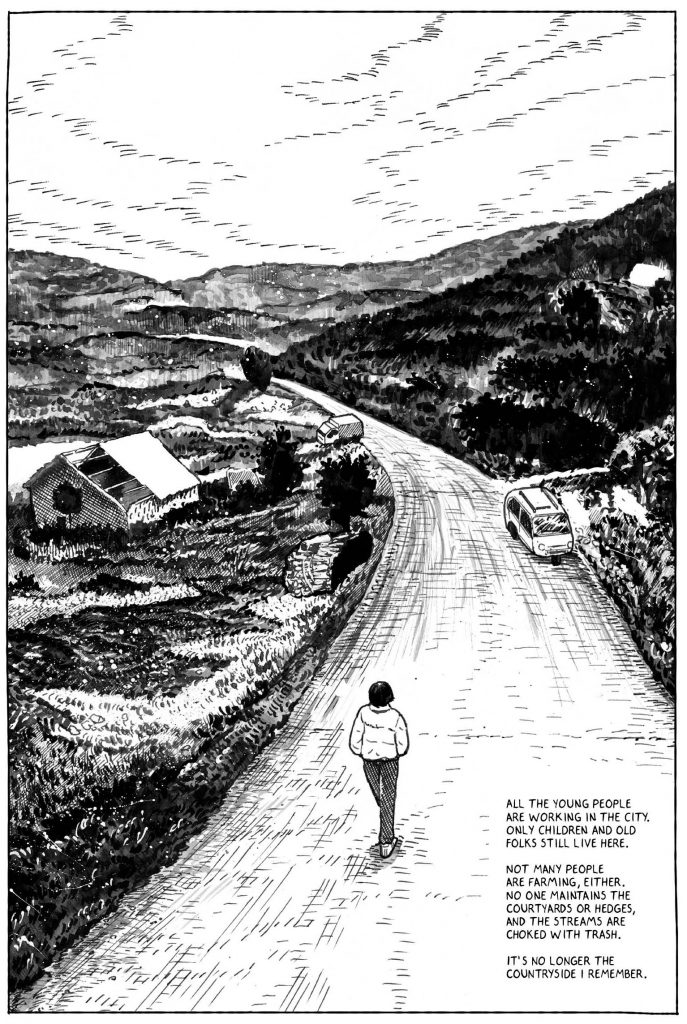

All of this is to say that I was struck by how close I felt to the world depicted in Night Bus, the short story collection by Chinese cartoonist Zuo Ma, published by Drawn & Quarterly a couple of months ago. Many of the stories in the volume are, in varying ways, inward-looking, a fragmented road map to Zuo Ma’s emotional state and personal life. The descriptor “dreamlike” is perhaps thrown around too often, having been flattened into a synonym for “strange,” but the dream-logic apparent in Zuo Ma’s stories is perhaps more faithful to the function of dreams, albeit in a manner that is separate, at least partially, from the innate weirdness in some of the stories: a theme that underlies his craft is the reflection, or the projection, of the internal on the external. Space becomes an extension of its inhabitant, as “self” and “surroundings” seem less and less like separate planes and more like the same one. This is maybe clearest in the stories involving the author’s grandmother and her cognitive deterioration; the Chinese countryside becomes synonymous with the grandmother, in a way that is simultaneously tangible and just out of reach. The author doesn’t appear to prioritize any grand-scale statement about the nature of place and space; while the scale of his imagination is outstanding, its anchor is firmly in the personal and the emotionally immediate.

A recurring theme seems to be Zuo Ma’s, or his stand-in’s, liminal existence: as we get to know him, we see him struggling to find his professional footing while also knowing rather clearly what it is that he wants to do, and we feel the frustration that stems from it. As is often the case in life, his emotions leave their marks on the spaces he occupies, and they manifest through his vivid imagination, which is rendered in a manner identical to the depictions of “normal” waking life; this going back and forth between reality and imagination could have been tedious, and even in this collection there are light lulls, but even the lower threshold is still remarkably high, as Zuo Ma’s deft hand keeps the reader engaged with his strong emotional mooring. As a result, perhaps the most tangible emotion in the collection is a sense of alienation. As Zuo Ma, as both creator and character, returns to plots and to places, they subtly shift, shedding some of their parts in favor of new ones—even though the human desire for familiarity would certainly prefer all parts to stay the same.

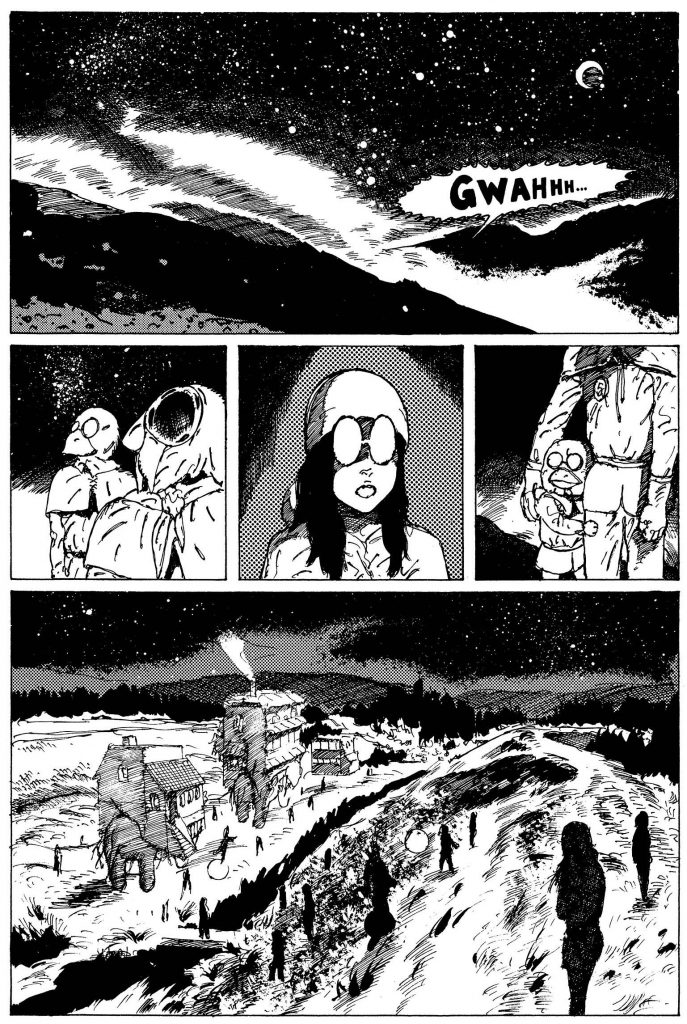

But, though themes and events recur, it cannot be said that this collection is really repetitive or one-note. If famous Jewish poet Rahel Bluwstein-Sela (often known simply as Rahel the poetess) wrote “only of myself did I know how to tell / my world is as narrow as that of the ant,” the same could not be said of Zuo Ma. Though his work dwells strictly within his world, his kaleidoscopic approach makes that world feel as large as a universe. Even the one story that is not inspired just by some form of Zuo Ma’s emotions and imaginings—Iwana Bozou, “adapted” from a Shigeru Mizuki story about the titular yokai—is made personal, as its context is transferred from Japanese folklore to the Chinese countryside, the external thus reframed as the internal. The way the cartoonist weaves between reality and its underlying emotion allows him to create a deep connection to even the outer reaches of the real; as the collection balances between the directly personal (which is to say, nonfictional, at least conditionally so) and the patently separate (most prominently embodied by the two short stories adapting dreams that Zuo Ma dreamed), the statement is clear: everything here is true, except for the parts that are patently false, and everything here is to be taken literally, except for the parts that are metaphorical; if you cannot determine which is which, it is because it does not really matter, because everything matters all the same.

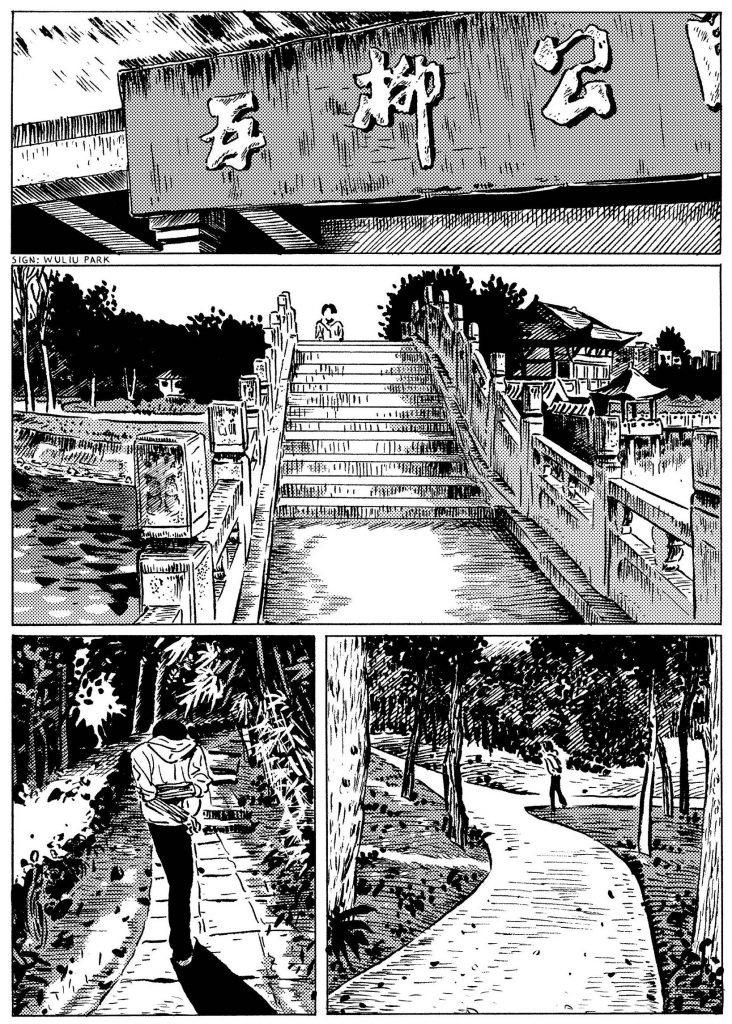

Zuo Ma’s art operates in lovely concert with the writing, moving back and forth between the same two forms of realism: the precise, representational, “external” realism, and its inverse, the dreamlike “internal” realism that while depicting the outlandish does so in a devotion to feeling and texture. The art gives the same significance to the real and the imagined, as if to say that any divide is arbitrary and not really necessary. An interesting tool employed in this collection is variation in line weight: Zuo Ma’s art is always attentively detailed, but some pages and images feel much more ink-drenched than others, which put me in mind of Japanese mangaka Taiyo Matsumoto’s use of rendering to shift back and forth between the impressionist and expressionist headspaces. Matsumoto, though, strikes me as much headier and more kinetic than Zuo Ma, whose hand, while certainly not static, is much more even and considered. It’s not that Zuo Ma lacks anything in propulsion, as much as he puts more of an effort in environmental immersion. The balance he maintains, between his accuracy in environment and architecture and those pools of ink that you could practically drown in, mean that the reader feels almost present in the art with the characters, or at least that they experience the surroundings as the characters do. It’s an impressive achievement, given that most of the book, except for exactly six pages at the beginning of the titular story, is in black and white; so total is his command of pen and ink that when you take a minute to consider the six pages painted in watercolor their presentation would almost seem unnecessary (I say “almost” because, though the six-page chunk of color swimming in the sea of ink might seem confusing, his hand is no less competent in watercolor than it is in ink).

The story that gives the book its name, Night Bus, almost does not belong in this book, having been originally published in China as its own standalone graphic novel. Published in 2018—five years after the final story in the collection, A Walk, was published—Night Bus displays an immense amount of creative progress; Zuo Ma is clearly the same cartoonist, building on the same lines that started his career, but the eight years between the first story in Walk and Night Bus’ present day turned him much more confident (although let it not be said that he didn’t start out confidently, as such a statement would be easily disproven by the rest of the collection), much more attuned to the best ways to say what he wants to say. It is an interesting curatorial decision, then, to present the two books not only as one, but also not entirely in chronological order—Night Bus appears as the fourth story in the English-language collection, sandwiched between a story published in 2011 and one story published in 2013. This choice could not be described as an aside, so to speak, for it commands too much of one’s attention to be taken as such a casual, offhand choice, but rather an evolution; a look into the bibliographical future that, while not quite remarked upon, is nonetheless pertinent to its surroundings.

This sort of exegetic flash-forward, however, is not uninvited or illogical—the stories in this volume occupy the same emotional and narrative spaces and overlap pretty significantly, to the point where one could be tempted to label the stories as a “shared universe.” Personally, I would shy away from this descriptor, if only because it signifies a sort of intent that Zuo Ma is clearly uninterested in. The “shared universe” approach is elected by a large chunk of commercial storytelling that exists to perpetuate intellectual property in order to frame narrative connections or overlaps as a shorthand for Significance, and so it is more often invoked as a marketing tool than a creative one; the stories in Night Bus, on the other hand, choose to overlap much more organically. But, though the intent diverges, the result is comparable: a rhizomatic rippling-out that almost rejects the common perception of where and how a story needs to begin and to end.

The book takes this idea one step further. As translator R. Orion Martin notes in his afterword— the cartoonist has made a habit of revisiting older works and editing them in hindsight, redrawing and rewriting as he sees fit. A rather prominent example of this is the version of the titular graphic novel that appears in English translation. If I’m understanding Martin’s description correctly, the version published here by Drawn & Quarterly is not at all the version published in China in that this edition sports not only redrawn pages and rewritten dialogue but also no less than fifty additional pages. Another good example is the fact that this collection opens and closes with what is more or less the same story in two variations, published three years apart, sharing a plot right down to most specific beats while displaying the progress in cartooning that the artist has made in the interim (a third version, fully colored in contrast with the previous black-and-white versions, is mentioned by the translator to have been published in Chinese five years later still, but does not appear in the English edition). While this approach is not unheard of in comics and in different media, it’s nonetheless a noteworthy approach, being, again, a fascinating rejection of boundaries; if convention is that the process of a work ends with its going to print and subsequently published, Zuo Ma throws this convention out of the window and makes work that is reborn and reshaped as he himself is reborn and reshaped, in total defiance of stasis.

Of course, this is simply underlying dialectic that, while contextualizing the work, is not itself the work, but I suppose the reason I am so enamored with this approach is because of how perfectly it aligns with the stories presented. I’m reminded of a bit of stage banter by the Mountain Goats’ John Darnielle, describing the song Never Quite Free as being about the “internal rear-view mirror” in which things “grow bigger and larger according to their own sort of calculus that you can’t really figure out,” which, in its own way, describes Zuo Ma’s approach perfectly—as time progresses and your perspective changes, if you are active in the creative arts, the way you relate to both the work itself and the objects that inspired it will inevitably change as well. Most creators will leave it at that, allowing the work to stand as a snapshot of that point in time, but Zuo Ma, while not meddling with the snapshot as such, will allow himself to revise it. His work is about the liminal, but the liminal itself changes as the two extreme points will change, letting the objects in the rear-view show their true face and significance. If, as Heraclitus is often quoted as saying, you cannot cross the same river twice, Zuo Ma will take pleasure in crossing it time and time again and making note of the changes in his reflection on the face of the water.

I am, as I write these words, 21 years old, freshly into adult life (if at all), and hovering around, if not quite having entered, the start of a creative career in comics. My grandmother, who lived in the kibbutz for most of her life, died almost four years ago; since then, I’ve only gone back for the funeral and subsequent memorial services. But I haven’t really gone back, not as such: after all, how can you go back to a place, when the reason for your visit is, quite literally, the death of the reason for your original visits? I am obviously not Zuo Ma, and the context for our respective experiences is vastly divergent; the geographical, political, and even personal circumstances are only superficially similar. But, though the reality of life cannot be compared, the emotional realities in Night Bus ring true; it is easy, and right, to applaud Zuo Ma’s skill for outlandish imagination and imagery, but even more worthy of applause is the underlying emotional infrastructure that gives that imagination its weight. The book is, then, the loveliest form of autobiographical storytelling: a marriage of emotions and the events that cause them, a merger of fact and fantasy, a breaking of the wall that separates the internal from the external. As wildly creative as it is lived-in, Night Bus is a beautiful ode to the in-between.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply