Somewhere within — or perhaps beneath — the hollowed-out shells of the one-time corporate “campuses” that comprise the makeshift community known, appropriately enough, as “Business Park,” there’s a mystery brewing: but determining precisely what that mystery even is in the first place is a mystery unto itself.

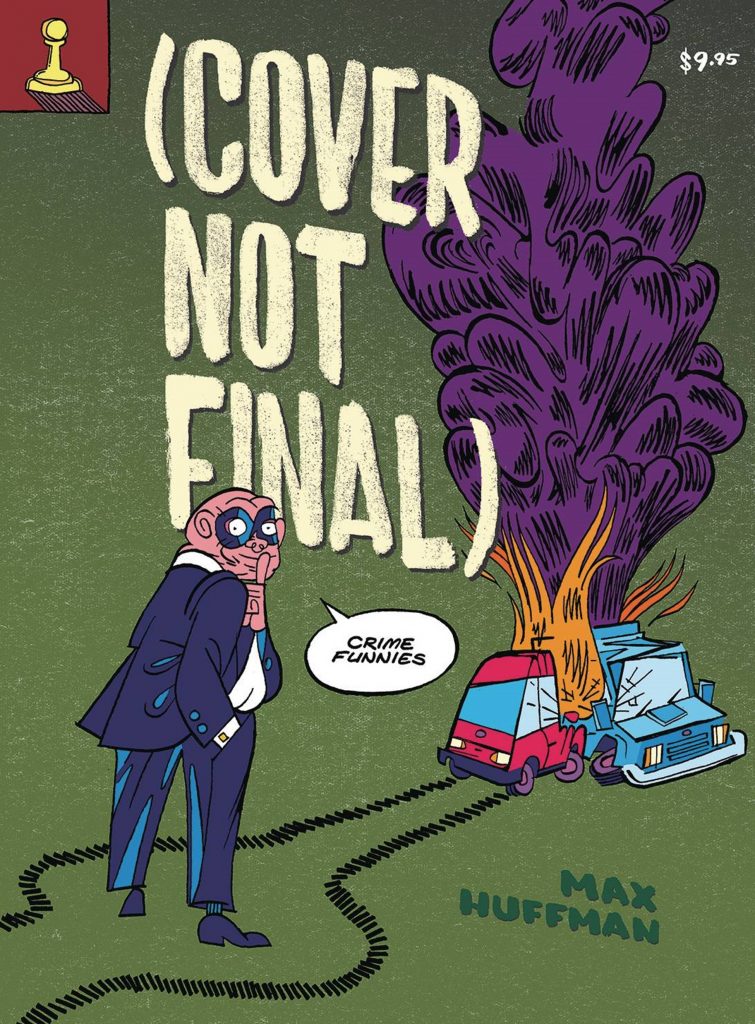

Which probably makes Max Huffman’s new little 64-page book from AdHouse, (Cover Not Final), sound more intimidating and unapproachable — or at least confusing — than it really is. Yet, works that defy conventional description or, at the very least, can’t be boiled down to the old reductivist “elevator pitch”, are often the most rewarding to spend some real time with, and, despite its admittedly short length, this comic definitely lends itself to re-reading and careful examination. That doesn’t preclude a person from taking it in stride if they wish, mind you — and you’ll likely get more than a few good laughs out of it and find yourself equal parts charmed and perplexed should you go that route — but if you’re predisposed toward being the sort of reader who enjoys piercing the veil and/or metaphorically peeling the onion, then you’ll really be in position to get your ten bucks’ worth out of this one.

Subtitling this “Crime Funnies” is a case of admirable truth in advertising on Huffman’s part, but, again, that’s only scratching the surface. The thread that connects each of the short-form strips contained herein is a tuxedo-bedecked career criminal known as, errrmmm, Career Criminal, but what he’s up to isn’t nearly so perplexing a question as why he’s up to it in the first place. Huffman gleefully plays around with standard-issue noir tropes (particularly in the strips featuring one Tennell Leffitt, who seems to occupy a space that’s halfway between being a real private eye and a well-connected trust fund brat playing the part), but, as with the multi-faceted approach Daniel Clowes took with works such as Ice Haven and Wilson, medium and message are both interconnected and utterly distinct from one another in more or less equal measure here; the key distinction being that whereas Clowes was laying out a fairly linear narrative after all was said and done, Huffman has created something more akin to a circular one. Indeed, with just a couple of exceptions, the running order of these strips could be shuffled around and the whole thing would still make just about the same amount of “sense.”

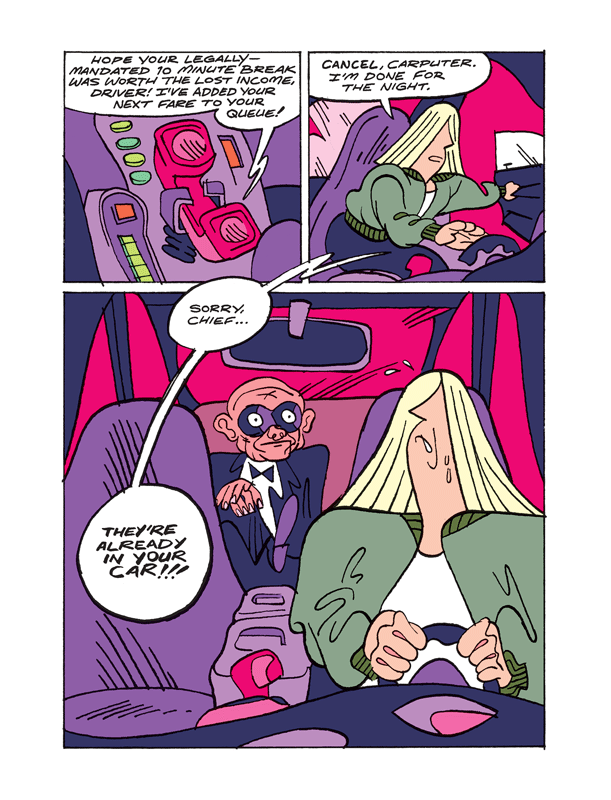

That’s a tricky term to pin down within the shifting stylistic context of this comic, I’ll be the first to admit, but the good news is that it’s probably not all that necessary to do so. Huffman gives scant few details about his characters or their makeshift world, parceling them out only to the degree necessary for audiences to limn their contours, so it’s best to be prepared to both go with his flow and to rely just as much on intuition as hard-and-fast evidence. I mean, we’re talking about a “city” where live music is illegal, and yet people are surprised when a popular music club folds up shop out of nowhere. Where recognizable socio-economic realities such as already-overworked office drones hustling up extra cash as Uber drivers in their off-hours rub elbows with otherworldly cosmic beings who hop between dimensions. Where illegal street racing is every bit the fad it is here in the real world, only they use city buses. You can — I’d even go so far as to argue that you should — ask how and why this all came to be, but by the same token, it’s perfectly okay to just accept something that feels both “right” and “true” within the context it’s presented in without stressing the particulars too terribly much.

One of this comic’s most alluring mysteries, though, doesn’t actually play out on its pages at all, but rather lies within Huffman’s own creative process. Some of these stories have appeared previously in parts various and sundry, and some are new, leaving me to wonder if he was playing a “long game” with this material all along, or if he simply decided at some point to tie things together, albeit admittedly loosely. Both prospects are interesting to consider, but the most remarkable thing is that the ultimate answer is simply that it doesn’t really matter much either way. It’s a remarkably effective work whether by accident, design, or a little of both, and the artistic gamut that Huffman runs by drawing each strip in a distinctly different style gives him a chance to show off his cartooning chops without being too, dare I say, flamboyant about it — I mean, we are examining the same place from multiple points of view, after all.

In the end — to the extent one can say this book “ends” — events and personages do tie into one another (in some cases even back into one another), but rather than close things off, Huffman leaves each narrative strand open to one degree or another, and that includes leaving them open to individual interpretation, as well. In my own readings of the comic, I’ve looked at it as being many things: an exercise in surreal humor, an exploration of multiple planes of reality existing simultaneously a la the Black Lodge of Lynch’s Twin Peaks, a particularly smart genre send-up os Kurtzman-esque proportions, a novel approach to the shopworn conceit of “world-building”.And I came to the conclusion that it’s all of them, at once, sharing the same small space, and somehow working together without crowding each other out. The real beauty of (Cover Not Final), though, lies in the fact that you can see it entirely differently and that we can both be right.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply